Kim Eull

Interview

CV

2015

“Why my drawing comes from the west” Baik Art, LA, USA

2013

“Two Rooms” Space Mom Museum, Cheong Ju, korea

2012

“Twilight Zone” Gallery Royal, Seoul, korea

2011

“hen, cow, dog, painting” Gallery soso, Paju-Haily, korea

2010

“so here… is there a bird ?” Space Gong Myung, Seoul, korea

2009

“Tears” SPACE CAN, Seoul, korea

2008

“Kim Eull Drawing ; Tear ” Ga Gallery, Seoul, korea

2007

“Miscellaneous Painting2″ Gallery Noon, Seoul, korea

2006

“Drawing is Hammering” Take Out Drawing, Seoul, korea

“Miscellaneous Painting” Gallery Ssamzie, Seoul, korea

2005

“Kim Eull Painting & Drawings” Baik Hae Young Gallery, Seoul, korea

<Selected Group Exhibition>

2016

“Inside drawing” Ilwoo art space, Seoul

2015

“The garden as a space” KSD gallery, Seoul

“Giving my heart to snoopy” Lotte Avenuel arthall, Seoul

“Your trip” Daecheongho museum, Cheongju

“City, Joy” Seongnam art center, Seongnam

2013

“Seoul Drawing Club-Two Drawing Project” SoSo gallery, Hai-ri Art Village

“Running Machine” Paik Nam Jun Art center, Yong-in

“House Who live in?” White block Gallery, Hai-ri Art village

2012

“Winter Wonder Land” Space K, Seoul

“Song of JINDO” Sinsaegye gallery, Seoul

“Museum in the Book” OCI Museum, Seoul

2011

“Tell me, Tell me” MOCA, Gwachun

“Ahn-Nyung/ Hello” Le Basse Projects, LA, USA

2010

” Drawing Palm ” Gue Mun Hwa, Seoul

2009

“Layered City” Artside, Beijing, China

“Safety First” Alternative space Choong Jung Gak, Seoul

“Big Boys”, Andrewshire Gallery, LA, USA

“scape of misunderstanding”, Zaha Museum, Seoul

“100 Daehangro” Arko Museum, Seoul

Critic 1

Kim Eull: Drawing Out One’s Self

Lim Dae-geun (Associate Curator, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea)

For about a decade, Kim Eull continually worked on his two series Self-Portrait and Blood Map, both of which focused on the theme of identity. Both of these series were essentially concluded in 2002, as Kim held a solo exhibition in Project Space SARUBIA. Given the history of that gallery as a stage for the unconventional works of experimental young artists, it was a pleasant surprise to find the artist in high spirits, having sporadically filled the space with landscapes and portraits. In the Blood Map series, Kim traced his family tree backward, moving beyond his previous efforts of self-exploration, which were more like mirror reflections of himself and the world surrounded him. But whether the topic is his family burial grounds in his hometown, or memories of his ancestors in pale black-and-white photographs, Kim’s ultimate interest is himself, and no one else.

Kim’s faded paintings are like artifacts excavated from the field after an intense battle, such that the pain of open wounds seeps through the canvas. Everyone who sees the works is struck by their unflinching sincerity, which resonates so deeply that viewers may find it difficult to look at them for too long. Kim’s heavy theme has been a double-edged sword, allowing him to delve deeper into his internal self but preventing him from advancing further into the artistic world. Like a monk practicing self-flagellation, he never deviates from his difficult yet determined path. For this exhibition, he also behaved like a historian, intensively researching his family’s genealogy, rummaging through public records, visiting his family burial grounds, and even measuring the land owned by his family.

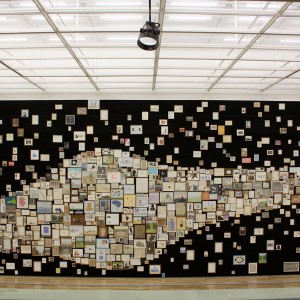

At the time, many viewers were curious to see whether Kim would obstinately continue to pursue his preferred theme or find a new subject to explore. Little did they know that he had already embarked in a completely new direction with an ambitious drawing project. Starting in 2001, Kim made 2,000 drawings over a six-year period (1,000 drawings in each three-year span). Exhausted by the solemn and personal nature of his previous theme, he began the new drawing project with a light heart, opening the door to a new world. By translating his incessant thoughts into impromptu drawings, he cleared his mind, and fresh ideas rushed to fill the space. These new thoughts came pouring out before he could find a theme in which to shape and contain them. The resultant works may be rough and unpolished, but they are “drawings” in the truest sense, representing his attempt to “draw out” the inner contents of his mind.

In 2003, Kim exhibited drawings from the first half of his project. The sheer number of drawings—about 1,000—was impressive, but even more overwhelming was the abundance of ideas in each drawing. As if the levee had broken, viewers were immersed in a veritable deluge of images and ideas. Anything that caught his eyes and his grasp became fodder for his drawings: the logo from a coaster in a café, bathroom graffiti, an old doll from a secondhand store, a diagram from a math book, etc. These diverse motifs were pulled through the filter of Kim Eull, thus becoming Miscellaneous Drawings, as he called them.

People who were familiar with Kim’s Blood Map series may have initially been confounded by the Miscellaneous Drawings series, which seemed to lack an overlying theme. But this can perhaps be expected with such an enormous number of impulsive works. Although some of the motifs were repeated, each drawing primarily existed as an independent presence, not unlike the disparate thoughts that make up our flow of consciousness. When asked why he had not pursued a connecting theme, Kim acknowledged that the weighty theme of his previous work had almost suffocated him. But as the drawings accumulated, he felt the pressure begin to dissipate, lightening his hands and his spirit and thus enabling him to make even more drawings. He has now been making the drawings for a total of about ten years. From the moment he gets out of bed, he does not plan what to draw, instead flowing freely through each day like water, without feeling distressed or restless. Maybe he was able to reach this state only after purging himself by taking his previous theme to the extreme. In this way, Kim’s task of making 1,000 drawings in three years is like a Buddhist who vows to make the “3,000 bows to Buddha.”

Amazingly, despite his incessant experimentation and varied expressions, Kim’s drawing series does not yield confusion. The lack of a coherent theme is simply an interpretation that arose in retrospect after the exhibition. In fact, no matter how varied his subject or method, all of Kim’s works—whether drawing, painting, object, or installation—are indeed united by a single, constant theme: Kim Eull. Like balloons of all shapes, sizes, and colors that are linked by fine thread to the balloon seller, the artist himself provides the ballast for the works, even if his presence is inconspicuous. As Kim said, his works are his “attempts to take full account of the world that is woven around me.” As such, Kim’s entire oeuvre may be viewed as a massive, sprawling self-portrait of the artist, who remains invisible yet present at the center.

This concept is best visualized in Twilight Zone (2011). In this striking image, Kim depicted himself with outstretched arms, holding a blue teardrop in his right hand and a turquoise teardrop in his left hand. He wears only sunglasses and a diaper that is inscribed with the word “honesty” (his personal mantra). A thin tube extends from his heart, through which blood pumps through a scientific beaker before spraying onto a canvas. Notably, the blood comes directly from his heart, before it has been pumped up to the brain, embodying the essential spirit of all of his drawings. The artist’s head has been split open, and a tree sprouts from his cranium, draped with a red sash that reads “MY BLOOD, TEARS, SEMEN…” The reference to bodily secretions hints at the physiological and existential conditions of the artist, as well as the characteristics of the art that he emits each and every day. Furthermore, he is flanked by two flags reading “1954” (the year of his birth) and “20□□,” presumably referring to his life span. By highlighting these objective facts, Kim demonstrates his ability to view himself and his art from a distance, even within this intensely personal work. Behind the artist are several blank or unfinished canvasses; a blue bird sits on the one furthest to the viewer’s left, while a green snake sits atop the one furthest to the right. In front of both the left and right canvas is a skull, likely symbolizing “vanitas,” and evoking Kim’s long-standing obsession with death. In the background is a low ridge holding two small placards marked with the letters “A” and “T” (respectively), representing his blood type (A) and the passage of time (T). The background is also occupied by several flying airliners and a military helicopter, symbolizing travel and adventure. Many of the motifs from this work also repeatedly appear in various forms in Kim’s drawings and objects.

When asked about the difference between painting and drawing, Kim replied that his drawings are not a political act. For him, politics is simply the desire to influence others by effecting an external façade, like someone wearing a full layer of make-up. On the other hand, drawings are completely honest and apolitical, like a person’s face at the moment they wake up, before they can even rub the sleep from their eyes. For Kim, a “drawing is not so much a painting as an inner attitude toward a painting.” Hence, while some drawings may resemble paintings, the visual aspects are not fundamental, nor are the materials or techniques; all that matters is the attitude of the artist. According to Kim, whenever an artist assumes the state of a blank piece of paper and begins to experiment with a new work, the result is essentially a drawing, no matter what it may look like. Based on this belief, he clearly cherishes the dangerous freedom of that blank state, and tries to spend as much time there as possible. He also said that an “artist is most true in a drawing….[A drawing] is strong, beautiful, true, and free.” In this context, all of Kim Eull’s artworks—including his objects, paintings, installations, and Blood Map series—are drawings, first and foremost. He once said that such “blood” flows, until his last drawing will be made from “a single teardrop made from the dust of my bones.” As such, Kim Eull’s drawings are a tool for drawing out his entire essence and scattering it to the world.

Critic 2

Drawings of Kim Eull:

Growing Houses and the Entire Landscape of the World

Kho, Chung-Hwan (art critic)

Poets always carry a notebook with them. Even today, when most people have switched to smartphones, poets still prefer to carry a notebook. Maybe this is because they have grown accustomed to the physical sensation of jotting down each word with a ballpoint pen. Whether it be a smartphone or notebook, poets carry something in order to capture the never-ending swarm of flashing thoughts, floating words, and flowing impressions of the world. Being captured unwittingly, these ideas and phrases usually do not follow any logical probability or causality. They are mostly recorded in some temporary form, to perhaps be summoned later and rearranged into an actual poem. Occasionally, however, the original notes become an independent poem themselves, maintaining their random, indiscriminate, and fragmentary form.

Poems and novels are very different. In novels, narration is very significant, along with the four main elements of plot: introduction, development, turn, and conclusion. Although these four elements can be rearranged or distorted, they are almost never dissolved or disintegrated. Poetry, however, has wider spaces between the lines, words, and sentences. Indeed, with poetry, the meaning often comes from the intervening spaces, rather than from the words or sentences themselves. If the spaces are too narrow, the meaning becomes cliché and conventional, but if the spaces are too wide, the meaning becomes obscure or disjointed. The plain meaning is replaced and saved by the strange, unfamiliar, and chaotic meaning. Indeed, the entire existence of poetry is predicated upon this process of replacing and saving.

In visual art, drawings are the equivalent of poetry: flashing thoughts, floating words, and flowing impressions. Unwittingly captured, accidental and indiscriminate things without any logical probability or causality. Fragments containing the self-sufficient whole. Things that are strange, unfamiliar, and chaotic. They are usually recorded as a temporary form, representing the potential or possibility of a painting. They are often meant to be summoned and rearranged to make a finished painting, but in some cases, they become paintings, in and of themselves.

The relationship between poems and novels is directly reflected in the relationship between drawings and paintings. At the superficial level, drawings are made as potentiality, while paintings exist as actuality or realization. As such, drawings might be seen as the periphery or surplus of paintings. They can also be a condition or dimension in the formation of independent paintings. Another perspective is to see paintings and drawings as institutionalized and not-yet-institutionalized works, or as realized and not-yet-realized paintings. In this way, drawings contain a radicalism, as self-awareness of the exterior territory, as well as a political aspect as a practice that contravenes logic and institution. But overall, drawings represent an individual and an independent style. There is no predetermined form or style to follow, no rules or premises. On the contrary, each drawing is its own form and style. Indeed, the radical and political features of drawings derive from this individual form and independent style.

Before Drawings

Kim Eull has fully dedicated himself to the craft of drawing since the time before his first exhibition, which was aptly entitled Drawings (2003, Gallery Doll and Gallery Fish). He switched his attention from paintings to drawings as a way to abolish his doubts about legitimacy in paintings, while also seeking to achieve a contemporary sensibility.

Kim’s doubts were particularly aimed at the deterministic idea that the quality of paintings comes from their relation to some prescribed form and definition, with a legitimacy that is ultimately granted by the art system. For him, the quality of a painting is not fixed, and each painting can be its own form and definition. This attitude emphasizes the act or process itself. Notably, around 1998, the majority of Kim’s works were destroyed in a fire at his studio. His subsequent focus on drawings was likely closely related to his realizations about the quality of a painting, or the “existence mode of art.” In the end, Kim came to see the fire as something of a godsend, freeing him from his previous conceptions and giving him the chance to be reborn as an artist.

Before switching to drawings, Kim was primarily a painter, and most of his works were from his two major series, Self Portrait (1994-1997) and Blood Map (1997-2002). Although these two series have some distinct qualities, they can also be connected as one, in that the self-portraits gradually expanded to involve Kim’s study of his own genealogy, or “blood map.” The self portrait extends into a blood map, which then serves as the premise for drawings that reflect a fragmented or multiplied subjectivity. In these two series, especially Blood Map, we can see the difficult yet sometimes jovial process of groping in the dark for the signifier of subjectivity.

Earth is known as the origin of life, because every living thing comes from and returns to the earth. New life forms are created every instant, and they rely on the earth for survival. As such, the earth provides countless connections for all of these beings, and those connections become dust, dirt, rocks, trees, rivers, and mountains. The blood of every being flows inside the earth, and the history of the earth is nothing but that of blood.

Kim Eull was born and raised at Oka-ri 265, Goheung-eup, Goheung-gun, South Jeolla Province. He made a series of paintings that deal with his family history, which he calls Blood Map, as well as Oka-ri 265. These paintings show scenes of family and nature, moving freely in and out without any boundaries. For example, people surge from the ground against a backdrop of wide mountains, where the family graves are located. In addition, on an old persimmon tree that has long protected the family house, each branch bears a person’s face, rather than a persimmon. The people seem to come directly from the mountains or the persimmon tree, implying that a family is nothing but earth, and that the history of the family (genealogy) is nothing but the history of the earth (the mountains), and simultaneously the history of blood (blood map). As such, the portraits of six generations, from ancestors to present-day offspring, are summoned into the present. These works convey some of the peculiar sensation that Kim once experienced, when he felt that a pine tree near the road into the mountains was like a gateway connecting past and present.

Kim’s paintings also incorporate maps into the background as part of the landscape. In particular, a woodland map and a cadastral map (showing property lines) appear, representing the attempted privatization of nature and the social act of establishing boundaries. These maps introduce the possibility of a social and economic reading of the landscape, a completely different way of seeing the world. Artist Kang Hongkoo has called Kim’s works “true-view landscape paintings,” recalling the genre famously created by the Joseon master Jeong Seon (1676-1759). This term reflects the belief that the natural landscape should be redefined in light of the new reality, wherein the right of ownership is routinely applied to nature.

Development Drawings: Ordinary Paintings and Miscellaneous Paintings

Switching to drawings, Kim Eull embarked on a series of formal experimentations that have continued to this day. At this point, it seems likely that he will continue to focus on drawings moving forward, or at least, that his scope of expressions will be diversified through drawings, and that these diversified forms (whatever they may be called) will help to expand drawings and redefine paintings. Kim initially decided to devote himself to drawings for about three years, but soon he was having so much fun with the drawings that he revised his plan. Perhaps his recent experience with drawings has changed his natural inclination and attitude towards paintings.

He has created an immense number of drawings, which can be generally classified into eight different series: Circle series (2004), CCTV series (2004), Miscellaneous Words of the Gapsin Year series (2004), Assemblage Box series (2005-2015), Tears series (2006-2010), Studio series (2009-2013), Twilight Zone Studio series (2011-2013), and Twilight Zone Drawings series (2011-2015).

For the Circle series, he first used a paper cup to trace circles on a piece of paper; then, inside the circles, he drew various images, wrote words, or pasted photographs, receipts, or other documents. As such, he found new ways to use geometry, as represented by the circles. To take it a step further, he liberated the whole existence of geometry from its framed form, thus problematizing every archetype. The CCTV series is based on the theme of a digital Panopticon, used as a surveillance device by the police-state. This series has clear sociological implications, as the possibility of latent (not-yet-committed) crimes is used to criminalize innocent and anonymous subjects. Exploring the exposure of naked, vulnerable life to sovereign power, these works recall Giorgio Agamben’s conception of the “homo sacer.”

Both the Assemblage Box and Studio series demonstrate Kim’s tendency to assign special meaning to the construction of houses. For him, building a house is not a simple act of construction, but rather the materialization of a two-dimensional drawing into a three-dimensional reality. Thus, the models of houses in these two series are microcosms of life. Likewise, the Tears series is more than just an exploration of emotions; it derives from, and thus invokes, life in its entirety. For Kim, drawing itself is an embodiment of life, simultaneously a crystallization and condensation of life. In this series, he takes the unique view of symbolizing life through tears, which may be interpreted as sympathy. There are countless theories about the reasons for creating art, but in the end, it can be boiled down to sympathy for other beings.1

Of all of these series, Twilight Zone is of particular interest. The word “twilight” conjures up images of half-light, dusk, and gloom. The term “twilight zone” usually refers to a vague, intermediate, or conceptual area, and it is also the name of the lowest level of the ocean to which light can penetrate.2 All of these meanings offer valuable clues about Kim’s artistic intentions and aspirations, as well as his ultimate destination. The twilight zone of the ocean is an abyss, permeated by silence and death. It calls to mind a basic and primordial state, preexisting names or language: the non-deterministic condition, the reversible and changeable condition, the unheard-of condition, the befogged condition, the disturbed condition within the silence of pre-meaning and not-yet-acquired signification, the condition with erased boundaries, the gaps, the corners, the frontier, and the surplus. By allowing himself and his works to settle in this uncertain condition, the artist seeks to re-establish his own existence. Discussing this orientation, Kim said:

Through drawings, I created my own world with new coordinates. I made a more elaborate map in which me, the world, and drawing are entangled with one another. With all these coordinates being constantly mixed, everything inhabiting my world was meaningful. That meant that there was no meaning or themes that could be captured from a special perspective. I think it’s much more fun and meaningful to see the whole and pay attention to their relationship.3….Isn’t it more natural for things to be mixed up, rather than rigidly organized? Although a fixed system can be truth, I think mixture is a more fundamental truth. Don’t life and nature exist in a mixed state without parameters?4

Hence, the twilight zone is both the foundation and the ultimate destination for Kim’s drawings, his other works, and his entire existence. Although this point can be represented on an elaborate map, it is actually a map of the artist’s own perception and creation, drawn in an independent style. In order to explore a map of such perception, we must penetrate into his independent style, where there is no subject matter and minimal meaning. After all, what is a subject matter? It is an attempt to collect, categorize, and type something that is inherently chaotic, fragmentary, indiscriminate, and self-sufficient. In this process, the essence of the matter is obliterated. It is the act of limiting, distorting, and subjugating what is self-sufficient outside the subject to the subject. Here, the plan to formulate a subject corresponds to a project of conceptualization, but there is an unbridgeable gap between the concept and the actual object. But in establishing a subject (or in planning to establish a subject), we should not seek to limit the object, but rather to bring the subject and object together in order to observe the results of their encounter. This process immediately evinces the helpless mixture of beings that is life, and it is this very mixture that inspired Kim to define his drawings as “miscellaneous paintings.”

My drawings are miscellaneous paintings. Although they sometimes yield unintended special subjects, they are basically a random mix of trivial things. My mind, life, world, and the whole universe are miscellaneous mixtures, which is why my drawings look so natural. Although their contents and forms are all mixed, some of the there must be things worth looking at, if you are careful about being cross-eyed.5

Usually, being “miscellaneous” means having nothing special to present, or being very ordinary. Another term for such a state is “motley.” Kim believes that his mind, life, world, and universe are inherently miscellaneous and motley, which means that they are common and plain. As such, is there anything that can truly be called abnormal or unusual? If his drawings are miscellaneous paintings, then they are ordinary paintings, capturing the banalities of daily life and existence.

In Korea, a general store that sells a miscellany of items is called a “store of 10,000 things.” Here, “10,000 things” is a rhetorical expression, standing for all the goods in the world. These types of stores, which are the prototype of contemporary department stores, have their own structure and system for categorizing items. But perhaps the epitome of a unique form of structure and categorization can be found in old bookstores. In such stores, all the books of the world are stacked and piled seemingly at random. Every customer is sure to feel completely lost, but the owner of the store can quickly and easily find whatever the customer needs. If knowledge is the foundation of power, as Michel Foucault famously asserted, then categorization and structure are the foundation of knowledge. Conventional, common-sense types of categorization and structure are not examples of abiogenesis (i.e., the development of living organisms from non-living matter). To quote Pierre Bourdieu, they are the result of recognition struggles. Although categorization may serve as a system and structure for an institutional device, independent agents are also capable of applying their own categorization and structure to various aspects of their lives, demonstrating their innovation in the process. Rather than a mere passive reception or inheritance, this may be seen as an active practice of appropriating categorization and structure as parts of the system, and re-distributing or replacing them in line with their own independent style. This is nothing other than art. In a more grandiose way, they have been unwittingly serving for the reorganizing and restructuring of the world.

Kim Eull’s art and drawings are a fine example of this phenomenon. What initially looks random and incoherent actually has its own unusual order and structure. He employs his own grammar of categorization and structure, arrangement and configuration, and relation and relatum. Although his grammar might initially seem somewhat distressing, at least he is engaged with finding his own grammar. Kim’s search for his own grammar may be related to the creative concept of the “Rhizome,” espoused by Deleuze, wherein one searches and creates through perpetual erasure, thereby conflating establishment and de-establishment. Like this, Kim pokes around in a store of “10,000 things,” or wanders through an old bookstore or flea market. These activities may be seen as an act of voyeurism, peeking into the lives of others. They are also related to so-called “found objects,” where one finds a former possession among a pile of dead, unfamiliar objects. It is also similar to the act of communicating with ghosts and using unusual objects to encounter the essence of a being.

Perhaps, the living things of the world are arranged like a store of “10,000 things,” an old bookstore, or a flea market. Just as today’s goods are slowly but continually becoming antiques, every living thing inherently contains its own death. Unfortunately, while many goods can actually gain value by becoming antiques, the same is not true of people. Perhaps this is why so many people seek to project themselves into commercial products. This is also why the most popular antiques usually look odd, unfamiliar, and grotesque. They are a fetish. Without this fetish, capitalism could not re-commercialize antiques (i.e., summon ghosts). This phenomenon has long fascinated some of the world’s great minds, including Georg Simmel, Charles Baudelaire, and Walter Benjamin.

In his own grammar, the artist collects, categorizes, reorganizes, deconstructs, reassembles, copies, and adds to the world. The objects summoned to inhabit that world convey a definite aura of the strange and grotesque, of the fetish. They also look like bricolage, which comes from the French “bricoler,” which means to make do with whatever is at hand, or to assemble random and unsightly detritus into something that works, or at least looks decent. Kim’s drawings arouse many of these same sensations: they look decent on the surface; raise some doubts at first glance; combine truth and fabrication; merge the everyday and the extraordinary. Through such drawings, he conjures and inhabits a twilight zone with obscure boundaries.

Expansion of Drawings: Building a House

For this exhibition, Kim Eull has actually built a house. It is built exactly like his own house, with his studio on the first floor and his living quarters on the second floor. For some, this project might seem a little “out-of-the-blue,” but various contemporary artists have engaged in similar projects, building homes or architectural models. One artist has constructed an ongoing house, which continually grows like a living organism. Another artist transported an entire library into an exhibition space. In fact, this is not even the first time that Kim Eull has built a house. After all, he worked as a carpenter for many years, earning his living by building houses. So he has built houses both real and virtual, for his livelihood and for his art. In the past, building houses was his life, and now building houses is his creative act.

Kim’s predilection for building houses can also be seen his Studio series and Assemblage Box series. The critic Kang Hongkoo has written about the meaning of building a house for Kim, and the relationship between houses and his drawings:

[Kim’s] house itself is a type of artwork, since he designed and built it himself. He once made his living building houses like this one, and now we can say that his life is drawings and making art….He changes everything around him into drawings, from his house to trees in his yard (with many dolls hanging from the branches) and zucchinis from his own garden, placed on a white plastic chair. His process of constructing a house or other building can be seen in the drawings of a small warehouse in his yard. The drawings meticulously document the entire construction process, from choosing the lot to putting in the foundation to completing the structure. Notably, both the warehouse and the documentation of the warehouse exist as drawings….His house is filled with his artworks, and his house is one of his artworks. He lives there. There is no separation between living and making art….He makes drawings in order to build his house. Then, he actually re-builds the house, and makes it into a three-dimensional artwork. Thus, his drawings are more like building a new house, rather than simply representing his house.6

Kim’s life, art, and drawings can be equated with building a house. Indeed, like a house, every artwork must be designed and built. Being the foundation of fine art, drawings can be compared to the zero point of our consciousness. As Heidegger said, language is the house of being, meaning that a being is expressed in language. Likewise, art is language; drawings are language; building a house is language. Kim Eull builds (expresses) his being and life in his own language. We might even say that every aspect of his life—eating, breathing, and thinking—is drawing. Eating, breathing, and thinking are essential components of life, as well as for building death, the completion of being. Drawings are not only building a house, but building a life, or living. Following Heidegger, drawings are his process of exploring, realizing, and expressing his very being. Every part of the process can be embodied as drawing. Thus, Kim’s building of a house is many different things: the accidental and random whole of drawings; the self-sufficient and sporadic whole built in the twilight zone with obscure boundaries; the fragmentary and momentary whole; the unfinished, ongoing, open, and disabled whole (since art is inherently disabled); and the whole under construction, to borrow Bahc Yiso’s expression.

Kim Eull is now opening a new genre, wherein the entire process of his art and his life is drawings. Or perhaps it is a “de-genre” or “multi-genre,” comprising nothing and everything at the same time. It could encompass any and all of the following: a miniature house; actual house; studio; warehouse; white lump; device for transforming an object into a person (and vice versa); portable landscape; shelf; bookshelf; antique display cabinet; table assembled from broken wooden panels; frames and boxes of varying sizes; mannequin; dummy; Barbie doll; ball-jointed doll; stamp made from a rubber eraser; commercial goods; found objects; magazine; ID photo; signs; pictures; texts; flea market; old bookstore; store of “10,000 things”; taxidermy bird; bird man; myth and incantation; painting with a green dot on the upper right; painting of nastiness; painting beyond a painting; ghost; difficult problem; peculiar space; existential space; precarious place; small cosmos; large self portrait; person standing squarely in the center; cow and ox; chicken; dog; somewhere between life and death; somewhere between consciousness and unconsciousness; erased boundary; scull; shabby toys; unidentified junk; cans; intersection of various narrations; objects belonging to different contexts; discarded items; things without the value of commercial goods; forgotten things; teardrops; bright tears; beautiful tears; red tears; seven emotions; globe; hammer; cart; car; tree; blood map; family tree; woodland map; cadastral map; files with serial numbers; private form; personal diary; stock chart from the newspaper; scale paper; painting of paper money; fish-shaped bun; kitsch; antique; CCTV; ratio of the circumference of a circle to its diameter (pi); humanitarian tastes and thoughts about collecting, gleaning, categorization; indiscriminate mixing of such tastes and thoughts resembling being itself.

Whether we want to call them images, paintings, or drawings, it will be fine. Conversely, whether we want to say that they are neither images, paintings, nor drawings, it will also be fine.