mixrice (Cho Ji Eun, Yang Chul Mo)

Interview

CV

2010

Transversal Project mixrice Report: welcome, my friend!, Art Space Pool, Seoul, Korea

2009

A Dish Antenna, Alternative Space Pool, Seoul, Korea

2002

Alternative Space Network – lucky Seoul, Alternative Space Pool, Seoul, Korea

<SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS>

2016

Made in Seoul, Centre d’art Contemporain Meymac, Meymac, France

2015

Memento, East Asian Video Frames: Seoul, Pori Art Museum, Pori, Finland

The Past, the Present, the Possible, Sharjah Biennale, Sharjah, UAE

Light of Factory Opening Exhibition, Maseok Furniture Complex, Gyeonggi-do, Korea

Jeju 4.3 Art Exhibition, Jeju Museum of Art, Jeju, Korea

2014

Gyeongg North Gosting, Makeshop Art Space, Gyeonggi-do, Korea

MDf Maseok Dongne Festival, Maseok Elementary School of Nokchon Campus, Gyeonggi- do, Korea

Read (residency East Asia dialogue), Research and Innovation Centre of Visual Art, TNNUA, Tainan, Taiwan

2013

SIASAT, Jakarta Biennale, Basement of Teater Jakarta, Taman Ismail Marzuki, Jakarta, Indonesia

nnncl & mixrice, Atelier Hermes – LA FONDATION D’ENTREPRISE HERMES, Seoul, Korea

MDF Maseok Dongne Festival, Maseok Furniture Complex Burnt Factory, Gyeonggi-do, Korea

Tireless Refrain, Nam June Paik Art Center, Youngin, Korea

Messages to Dhaka by mixrice, Sai Comics, Seoul, Korea (publication)

2012

MDF Maseok Dongne Festival, Maseok Furniture Complex 488-32 Rooftop, Gyeonggi-do, Korea

Asia Pacific Triennale, Queens Art Gallery, Brisbane, Australia

Seoul International New Media Festival poster & trailer by mixrice and mixrice Special Screening, Media Theater Igong& Korean Federation of Film Archives, Seoul, Korea

Continuous Art, Impossible Community, 3rd Residency Artist Open Studio, Seoul Art Space GEUMCHEON, Seoul, Korea

Gunsan Report : operators of survival and fantasy, Art Space Pool, Seoul, Korea

2011

Gunsan Project Twists Turns Ups Downs (In)visible Move and Human Agency , Gunsan, Korea

Interview, Arko Art Center, Seoul, Korea

ILMAC ART PRIZE ILMAC Foundation for Arts and Culture, Seoul, Korea

Badly Flattened Ground, Seoul, Korea (publication)

2010

Against Easy Listening, 1A Space, Hong Kong

RM Flag Project, Auckland, New Zealand

Last Summer, Exhibition and participation in the book, Seoul, Korea

Dual Mirage Part 1, Participation in the book, Seoul, Korea

Research residency in Townhouse Gallery of Contemporary Art, Cairo, Egypt

A Frog in the Valley Travelled to Sea, Seoul, Korea (publication)

2009

Bad Boy Here and Now – new political art in Korea since 1990s, Gyeonggi-do Museum of Modern Art, Ansan, Korea

Double ACT, Sabina Gallery, Seoul, Korea

The Antagonistic Link – electric palm tree, Casco, Utrecht, The Netherlands

2008

Mirant Fortune Cookie, Take Out Drawing, Seoul, Korea

Migrant Flag, Migrant Arirang Multicultural Festival, Olympic Park, Seoul, Korea

Critic 1

Absolutely Unmixable, but…

Jang Un Kim (Head of Exhibition Team 2, MMCA Seoul)

There was nothing extraordinary about the origin of the art collective mixrice. In their early works (2002-2003), they researched the establishment, development, and demolition of Seoul (particularly certain outlying areas), conducting an in-depth examination of the lives of the middle- and lower-class residents. In the process, mixrice showed how actual urban spaces could formulate the class background of the people living there. Like many socially engaged art projects, their creative research (which recalled the work of the Situationists) employed methodologies borrowed from anthropology. Although the group was clearly excited by these early works, they seemed unsure about their next move. Then, they encountered the community of foreigners working in Korea.

Before naming themselves mixrice, the group members visited factories in an industrial area near Seoul, where they provided media education programs for foreign workers. These programs mostly consisted of teaching the workers how to make videos, i.e., how to use a video camera and editing programs. Encountering these workers, who seemed eager to acquire skills that they could use in their home countries, the members of mixrice unknowingly found themselves confronting one of the most profound problems created by globalization. Rather than meeting white people, or black people, or Asian people, they met “X.” X is invisible, but exists; X is nameless, but has a name; X is alive, but dead.

mixrice cannot be narrowly understood as a group of artists dealing with the problems of foreign workers, particularly those in Asia. Meaning “mixed rice” in Konglish (Korean-English), the name “mixrice” represents a certain cross-section of contemporary globalization. In this globalized world, foreigners are not seen as a subject to address, but rather as an object to be addressed. The name “foreigner” is not a proper noun, but rather a flexible label with many connotations, depending on the situation. It can be a scarlet letter, a stigma of contamination and impurity, or simply a designation that reveals our inability to define a foreigner. None of us are exempt from this label, for in this era of Neoliberalism, we are all foreigners in one way or another, even if most refuse to acknowledge it. In order to inhabit the arbitrary boundaries regulated by globalization, we need to identify foreigners and furthermore, to constitute foreigners as the Other. All the while, we blithely ignore the fact that we ourselves are the foreigners.

By interacting with foreigners, mixrice learned how to talk alone and together, as an individual and as a community. Through their media classes, they provided the foreign workers with a camera and asked them to document their lives, thus enacting Video Diary (2003). The ultimate goal of the project was to transform the foreign workers from passive objects of representation into active subjects. Through this process, mixrice force us to reflect on a number of compelling issues: “us and them,” national borders, the people traversing and lingering around those borders, the whole world, and again, a specific community.

After Video Diary, they worked on a series of projects (e.g., Mixrice Channel [2003-2004], Marquee Theatre [2004], Return [2006], Migrantcart [2005-2006], Hotcake [2004-2005]) that also involved diverse processes of collective creation, collaboration, and communication. In order to receive and share stories with anyone, the group members learned to speak new languages and gained new perspectives on the world from foreign workers. As such, mixrice utilized the medium of labor to immerse themselves in myriad complex issues related to a Korean society that was being transformed from a racially homogeneous nation into a multiracial one.

Mixrice Channel consisted of various themes, the first of which was Why Willing to Kick out Old Friends? (2003). This project was held multiple times at different venues, including an exhibition, a multicultural festival, and a protest against globalization; at each site, the group would set up a tent and host a talk show. In some sense, the title—Why Willing to Kick out Old Friends?—recalls the slogan “We are all German Jews,” which was chanted by French students during the protests of May 1968. It also alludes to posters reading “Foreigners, Please Don’t Leave Us Alone with the Danes,” which were plastered across Denmark in 2002 by the Danish art collective Superflex. In considering these phrases, it is crucial to recognize the subject who is speaking. Facing questions about the racial identity of their leaders, the students involved with the 1968 protests felt compelled to assert the righteousness of their cause. Through the slogan “We are all German Jews,” they proudly proclaimed that all the subjects of their revolution were outsiders viewed by the mainstream as “contaminated.” As such, they elevated their cause from a regional protest into a universal issue for all of humanity. As for Superflex, the posters were addressed to foreigners who had been deported, and the “us” in the sentence refers to all of the people still living in Denmark, Danish and non-Danish alike. Finally, in the mixrice project, the term “old friends” refers to foreign workers and other friends who have been “kicked out.” Thus, it is left to those who remain to question this issue. In other words, mixrice is emphasizing that this is not someone else’s problem, but our problem. By addressing a subject not from the perspective of identification, but rather from the perspective of subjectification, mixrice conceives a new relationship between myself and the Other, thereby enabling us to imagine a new type of community.

Maseok is an area near Seoul that carries different associations for different people. In the wake of the Korean War, Maseok was occupied by a community of people with Hansen’s disease (also known as leprosy), but today, most people know it as a major district for the production and sale of furniture. But for the members of mixrice, Maseok is the site where they live with their friends and colleagues. After working closely on various socially engaged projects, mixrice found that they were of one mind with the foreign workers, and thus began to consider ways to live side-by-side with them. Many of their close friends had settled in Maseok, an isolated and obscure place that has largely been ignored in Korean history, despite its proximity to Seoul. After the Korean War, people with Hansen’s disease wandered through Korea before forming a village in Maseok, away from the prying eyes of others. Through the rapid industrialization of Korea, Maseok evolved into a center for furniture production, supplying the people of Seoul with tables, chairs, etc. Over time, the Korean workforce was largely replaced by foreign workers, including many of the friends of mixrice.

Marking the beginning of a new set of explorations, Dish Antenna (2008) examined the urban space of Maseok in the context of the daily lives of the workers. In particular, mixrice correlated the lives of the foreign workers with the cultural and geographical significance of Maseok in Korean society, showing how the workers embody the restriction and alienation that have come to be associated with Maseok through the era of modernization and industrialization. The foreign workers laboring in small furniture factories are physically isolated from the Korean community, but that isolation is exacerbated by numerous ethnic, religious, and national categorizations. Collaborating with the workers, mixrice produced a theatrical play entitled The Illegal Life (2008). In the course of the production, the group met with many individuals representing various facets of the above-mentioned categorizations, and listened to the stories of their lives. Beyond simply turning the lives of the Maseok workers into a theatrical play, mixrice provided an open performance space where hundreds of marginalized people could speak about their lives. The project has since been expanded into a festival format, eventually becoming the Maseok Dongne Festival.

The activities of mixrice are not bound by any certain political struggle. Instead, they are constantly changing and traversing life’s boundaries, like memories of the past, and our present perspective of those memories. These lives and memories are not only those of foreign workers in Korea, or those of the members of mixrice; they belong to each and every one of us. After all, who among us is not cast out, exiled, alienated, torn and tattered by life? Using this point as the foundation, mixrice is creating a new story for an alternative community.

mixrice embodies two critical aspects and duties of the Korean art of today. First, they undermine the uniformity or specificity of Korean contemporary art that the nation-state, formed by racial homogeneity, wishes to establish. Second, they are working to establish an ecological community uniting life and art in ways that transcend national boundaries. Working together with their colleagues, mixrice has realized many amazing achievements on both of these fronts, as they continually manifest new possibilities of art.

Critic 2

Toward the Outside: In Pursuit of Resonant Objects

Young Min Moon

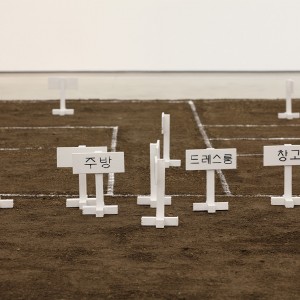

Capital is what enables an empty plot of land to be flattened for the construction of a new building. Painted in white on the surface of a low rectangular block of earth is part of an apartment floor plan in reduced scale. Within the boundaries of each room stands a short sign that spells out living room, ondolbang,1 bathroom, etc., while signs reading kitchen, dressing room, storage and several others awkwardly congregate outside the floor plan’s parameter as there are no rooms to accommodate them. Crudely painted directly on the earth, the installation is a reconstruction based on an archival photograph of an apartment floor plan. Located in what is now the Gangnam area of Seoul, the land in the photograph had been slated for the construction of a new apartment complex in the early 1970s. The painted floor plan, which evokes an old Korean childhood game involving hopping on one leg after throwing a pebble to claim sectioned areas, is a distant ancestor of the now commonplace “model house” featured in actual size in many real estate showrooms.

Meanwhile, silhouettes of plants rendered in black spray paint on the gallery walls appear as though they have been overexposed to light, as if glaring light has been shone over them, or perhaps as an afterimage of smoked plants. In contrast to the earth, the shadows of the repeated plant forms are dematerialized and appear as silent witnesses in the wavering wind. The plants used in this fossil-like graffiti, which conjures up the image of entwined creatures, were found in the areas designated to be submerged in the Four River Project as well as around the redevelopment areas in Seoul and Gyeonggi Province. Prior to being painted, the plants were dried by keeping them pressed between papers for an extended period of time. In contrast to the images of the ever-expansive plants, the rectangular earth and the floor plan are flat and small in scale, perhaps suggesting that the plants belittle man’s enterprises. Somehow, such contrivances of man appear to be haphazard and even pathetic in relation to the ghostly presence of nature.

The series of black and white photographs represent trees subjected to various circumstances: an old tree with its cropped branches replanted in an awkward position next to a gazebo; an old apartment building slated for demolition for redevelopment along with the surrounding trees; some root fragments after the destruction of a tree in Naeseong Stream, part of the Four River Project; and some trees transplanted, illegally or otherwise, as part of landscaping projects. The two-channel video The Vine Chronicle (2016) includes images showing Halmangdang (Grandmother Shrines)2 and deity trees surrounded by vines on Jeju Island; the residents of Yeongju Dam, with their village, about to be submerged, in the background; the radically different ways in which developments unfolded in the Gangnam and Seongnam apartment complexes; and views of redevelopment areas. All of these places are marked by both the presence and absence of trees by means of transplanting.

In recent years Mixrice took on plants as a main motif of investigation. With their 2013 exhibition at Atelier Hermès in Seoul, which focused on the migration of plants, Mixrice broadened their thematic scope. They began to regard the history of migration through the intersections of imperialism, colonialism, and migration of plants. Mixrice now probes the phenomenon of migration through the transplanted trees associated with the development of apartment complexes and the emergence of the middle class in South Korea over the past five decades. They dismantle the binary perception of migrants versus settled and question the notion of settlement by following the transplanted trees, some of which are found dead. Maintaining ecological principles and an anti-capitalist positionality, Mixrice looks deeply into the vines that are synonymous with vitality. Observing the ability of trees to take root and settle in any way possible, Mixrice reflects on the resilience of plants, which resist the violence of development and forced transplantation.

The practice of Mixrice is a situated one that responds to constantly shifting circumstances. Therefore, the process is of utmost importance and the work manifests in a variety of forms. As curator Heejin Kim noted, it is important to remember that Mixrice does not establish a concept first and then follow through by making an artwork; rather, their concepts emerge in the process of their activities.3 At times Mixrice exhibits works made as byproducts of their collaborative activities with social Others. That is, they do not make these works for the sake of making them. They are not simply photographers, sculptors, or installation artists per se; nor should they be referred to as cartoonists, muralists, or documentary makers. But they freely use all of these mediums and methods, and such a sense of freedom stems from their meeting with, listening to, and reflecting on the people, things, and energies they encounter at specific times and places.

This essay considers Mixrice’s multi-directional activities. Participating in the Artist of the Year exhibition at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA), Mixrice demonstrates considerable aesthetic restraint. However, given that the exhibition includes an archive of their past work, I consider it an opportune occasion to reflect on their work of the past fifteen years. While I will briefly look at the social context in which Mixrice was formed, their intentions, and work processes, I will elaborate more on the evolution of their work in recent years. This essay will examine how Mixrice regards the phenomenon of migration, why and how they focus on migration through the lens of plants, and why apartments begin to appear in their new work. In the end I shall offer some thoughts on the meaning of their multifaceted practices.

From Migrant Workers’ Human Rights to the Phenomenon of Migration

Around the time of the 1988 Seoul Summer Olympics foreign migrant workers began to arrive in South Korea to take up the physically demanding and dangerous jobs unwanted by Koreans. The flexible neoliberal system in full force after the 1997 Asian financial crisis further facilitated the influx of migrant workers. However, their presence became publicly known only when mass media began to highlight their vulnerable conditions: the workers were traumatized by labor exploitation, human rights abuses, unpaid wages, and fear of deportation. Mixrice, which was founded in 2002, was dissatisfied with such media representations that relied on sensationalism and aimed at soliciting sympathy from Korean citizens. Instead, Mixrice attempted to find new ways of representing and communicating with migrant workers, transcending the media’s stereotyping, humanitarian gaze by sustaining a loosely organized, but ongoing relationship with the workers. For Video Diary (2002-03) the artists helped the workers record interviews with one another, edit the videos, and screen them at public venues. They organized and performed Human Rights Skipping Rope as part of a participatory demonstration to raise public awareness of migrant workers’ human rights issues. They also made Hotcakes embossed with the text “Stop Crackdown!” to be consumed at demonstrations and sent in bulk to the immigration bureau. During an extended demonstration inside a tent situated within the parameters of Myeongdong Cathedral in downtown Seoul, Mixrice produced talk shows with the workers and broadcast them in real time. They collaborated with the workers in creating Mixlanguage, a song with lyrics consisting of humiliating directives commonly yelled at the workers in Korean factories. Music Café later showcased the stories behind the music and the experiences of the workers. Based on establishing rapport and sustained dialogue with the workers, the social practice of Mixrice also included workshops and video tents, as well as a wide range of forms including calendars, photographs, cartoons, wall drawings, and videos. Meeting with migrant workers and having dialogues with them are prerequisites for the visual works.

The evolution of Mixrice over the past half dozen years stems from their critical reflection that their early communication and collaboration with migrant workers may have resulted from a “closed reciprocity and a gesture of tolerance,” even if intended as a way to overcome the humanitarian gaze. Tolerance may be regarded as a generous attitude that embraces the Other who is somehow different from us. However, that is not so different from positioning the Other as a beneficiary of tolerance, which ‘we’ bestow upon them. The politics of tolerance helps us realize that the notions of ‘giving voice’ to someone or ‘empowering’ someone is paradoxical, for these are inherently hierarchical notions that presuppose that the beneficiaries have no voice or power to begin with, and are thus rendered vulnerable as they cannot speak up or make themselves visible on their own.4

In hindsight, we can see that Mixrice began to show some concrete changes in their work around 2010. First of all, what has not changed is their continued focus on the process of activities and interactions with migrants. Another constant is that their work is never predetermined in terms of medium but rather follows their responses to encounters with Others. What has changed are the circumstances surrounding migrant workers. Unlike the past, labor unions no longer congregate or undertake demonstrations for human rights issues. Instead of shouting “Grant labor visas!” Mixrice has turned to the city of Maseok in order to be active in the very midst of where workers live and work.5 Having shifted away from their previous political interventions, they are now more concerned with the question of what it means to coexist with the workers. The changes in their work pertain to the ways they respond to the changed realities for the migrant workers. Certainly, they have shunned away from blindly producing ‘finished’ art objects from the outset and have kept the forms of their work variable, all the while investigating the intersections of art and the political. Importantly, the work of Mixrice is not limited to the theme or the subject of migrant workers. They have increasingly expanded their interests from workers’ human rights issues to the complex phenomenon of migration. While continuing their interactions with foreign migrant workers in Korea, Mixrice has recently completed projects based on interviews with Korean migrants within and beyond Korea: those who have moved from the rural areas to the city and those who have left Korea for other countries. As well, they have conducted extensive research on the history of migration in modern Asian history. Mixrice also hosted Maseok Dongne (village) Festival, or MDf, a rock festival for the migrant community in Maseok for three consecutive years.

MDf, or Maseok Dongne (Village) Festival

Located in the northeast about an hour from Seoul, Maseok was once home to many people with leprosy. Now there are large furniture factory complexes surrounded by residential districts where migrant workers reside. Tucked away behind a range of mountains and a golf driving range, Maseok is characterized by toxic chemical fumes and outdated factory facilities that harken back to the 1970s. Visiting Maseok is a strange experience, like time traveling to the past. Except here one encounters migrant workers. For a number of years many of the workers suffered injuries while trying to avoid the crackdown imposed by the previous administration of President Lee Myung Bak, or were arrested and deported to their home countries. The migrants have been in a quandary since then, wondering if they should return home or relocate to another place and carry on their precarious state of life. Despite the impoverished conditions of life and work, and the ensuing anxieties, many migrant workers consider Maseok their second home.

Cognizant of such locational specificities of Maseok, Mixrice has witnessed, and at times participated in, the emergence and evolution of a contingent community. First held in 2012, the rock concert called Maseok Dongne (Village) Festival, or MDf, began because of what Mixrice happened to learn through continued visits and casual interactions with the migrant workers in Maseok. Although the workers loved rock music, they could not attend existing commercial rock festivals due to their grueling work schedule. So they expressed their wish to have a festival right in Maseok, and Mixrice decided to help them materialize their wish. The abbreviation MDF actually stands for medium density fiberboard, a common furniture material, but Mixrice’s appropriation of the term gave it a witty spin. MDf came to fruition by the efforts of the artists, their friends, and the audience, who volunteered to help out from beginning to end on all tasks from organizing to the cleanup after the concert.

One day in October that year I arrived with Mixrice in Maseok many hours before the concert. The concert was to take place on the roof of an old factory building where mounds of discarded industrial waste had been cleared away. An empty space was created on the rooftop, not to construct a building but to create a space for people of different races and diverse social classes to mingle. Here and there were drums holding firewood and fluorescent lights. Musicians began arriving, performing sound checks and warming-up. As the dusk set in, the aroma of curry and Bangladeshi fried rice in large kettles filled the air, while people arrived and began to settle in. Though the audience was made up mostly of migrant workers and their families, there were also many Koreans, including a Catholic priest and Protestant ministers, ‘illegal’ workers, and a local detective and his family; it was a gathering of people not usually found together in one place. A female worker from the Philippines opened the concert, followed by several underground bands, and the workers joined them, dancing in front of the stage. When Sultan of the Disco performed their disco music a middle-aged man in a turban became so visibly excited that he fell while dancing, causing many around him to fall together. I vividly recall how his turban unraveled as he got up and tried to regain his composure.

While MDf was entertaining and entirely enjoyable, it also operated on several other levels. First, it was an effort to materialize the dream of culturally alienated workers. As most of the factory buildings in Maseok were built illegally, they were not even registered or included in the official maps. Many of the workers also had ‘illegal’ status. Thus, MDf was a party of “undocumented people” held at an “undocumented place,” an attempt to enjoy “a night of music with non-existent people at a non-existent place.” It was a result of Mixrice’s positive reply to the workers’ proposal to thrust “a romantic moment into a cruel reality.”6 Furthermore, the festival was a special occasion in which the foreigners became “another kind of subject” and invited the ‘insiders,’ i.e., Koreans, to join them; certainly a rare occasion for Koreans to “encounter a darkness in the suburb of Seoul in a different way.”7

The festival is located on a continuum with another Mixrice project, Illegal Lives (2010), a play authored and performed by migrant workers who constitute Maseok Migrant Theatre. Mixrice assisted in the production of the festival, just as they had in the production of the play. Although Mixrice, the invited bands, and the sound engineers did a huge amount of work, it was nevertheless a response to the workers’ request. The festival could not possibly compare to rock festivals organized by large capital. As such, it was a modest-sized, humble event for a neighborhood. However, the participating musicians were not necessarily amateurs, as Kangsanae8, who replied enthusiastically to the call, was among the invitees. On another note, there were social contradictions to the festival, such as the presence of ‘illegal’ workers alongside a local detective, as well as moments that could transcend them. The festival took place in the liminal space between the “institutions of music, art, national borders, religion, industry, and housing.” Aesthetic considerations were also notable, and plants were introduced, albeit not for the first time. Mixrice had retrieved discarded plants and conserved them, and placed them in pots throughout the site, while large leafy shaped fabric pieces interweaved the stage and the space for the audience.

Although the annual festival was successful, Mixrice stopped holding it after two more years. The decision was made after contemplating the changing circumstances of their collaboration with the workers. Mixrice was mindful that the festival could easily become formulaic and institutionalized as it was repeated. The duo strives to generate situations and activities that the migrants and they themselves find interesting and enjoyable. As the circumstances change they determine what they want to do, and the forms follow accordingly. Mixrice does not meet migrant workers in order to do so-called ‘community art.’ They do not simply enter the ‘community’ and do some ‘art’ and leave. Instead, Mixrice pursues a variety of activities and works over an extended period of time as a will to express a genuine interest in the lives of migrant workers and to explore what it means to coexist with them. All the while they acknowledge and maintain both a physical and psychological distance from them. For Mixrice to meet the social Other is to practice something in recognition of an uncomfortable truth. Mixrice imagines and practices in “a field in which diverse communities coexist, where people from diverse cultures gather, encounter, and run into each other.” In regard to MDf, they emphasize that the migrant community and the artists once shared “a mutual expectation about [creating] a certain situation,” and they intend to recuperate this. It is such shared expectations that mobilize their collaboration, so Mixrice expects the migrant community to renew their will for continued collaboration.9

Many examples of art that are discussed in terms of Relational Aesthetics tend to have “feel-good”10 moments; given that the focus on convivial gatherings of artists and participants tend to overlook the concrete social problems that they face, such art is often criticized as inadequate. Hal Foster criticized the fact that such art neither brings about “social effectivity” nor offer “artistic invention,” and “one criterion might become the alibi for the other.”11 Claire Bishop pointed out that the common trait among socially participatory and interventionist art was that artists often attempted to ameliorate specific situations, not unlike good Samaritans, often at the expense of both aesthetics and politics.12

What about Mixrice? While their early works, such as Video Diary or Hotcakes, clearly show an effort to improve reality, is Maseok Dongne Festival somewhat removed from such ameliorative practice? Interestingly, when I posed the question, “Was MDf an occasion to experience reality in a more intense way?” Jieun Cho and Chulmo Yang of Mixrice offered contrasting answers. Cho conceded, adding that they strove to intervene in reality and improve the situation through their early works, but it was no longer the case in recent works. However, Yang offered that even MDf was a solution to reality. For the migrant community in Maseok appeared to “lack joy in life,” and “it was an expression of our will to coexist with them.”13 In that regard, MDf was indeed a solution to the absence of solidarity, and to the dreariness of everyday life there. But it was no longer a means to seek solutions to specific issues or interventions in labor policy; rather, it was a temporary solution to express a will to live together, an attempt to seek out diverse ways of being together. It may be paradoxical that the two artists have different opinions, but I consider such contrasting positions as healthy.

Aesthetics, Politics, and Paradoxical Truths in the Work of Mixrice

One way for Mixrice to reinvigorate their practice has been to publicly share criticisms of their works in their own publications. As artist Seung-Wook Koh has pointed out, the activities of Mixrice take place outside the institutions of art but they are given recognition within them.14 Koh’s observation is correct when one considers the outdated factory complexes and migrant community in Maseok alongside influential venues such as Atelier Hermès or MMCA. Despite this, Mixrice does not separate the inside of an institution from the outside, but rather links the two in an organic way. They provide or facilitate constructed situations, create various kinds of meetings and platforms for solidarity, or make art objects in a traditional sense and exhibit them. At times they exhibit documentations of their activities, such as the Maseok Migrant Theatre’s play, and other times they exhibit their own interpretations of them. Certainly their work must provide access to two different types of audiences: that is, at the site of their activities their work must yield an effect on “those who are directly involved” and foster solidarity with them, while within the institution, their work must offer “a highly elaborate, intellectually complex, and problematizing project.”15 This presupposes that a ‘passive’ audience is not a bad thing, that what is usually regarded as ‘passive’ is not necessarily passive in the literal sense, and that it reflects Mixrice’s position that what is important is the nature of how participation occurs, rather than whether the work involves participation or not.

In the trajectory of Mixrice’s work there have been several turning points. These important moments testify that Mixrice does not simply follow some utopian vision but rather internalizes certain complex social contradictions that operate at different levels. Participatory art that implements social practice always involves debates on many fronts, including the political relationship between the artist and the collaborators, the degree and nature of the participation in relation to the quality of the work, and the nature of the audience’s experience of the work. One criterion for assessing participatory art is the presence and nature of antagonistic relationships. Borrowing from the theory of radical democracy by Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe, Claire Bishop emphasizes that radical democracy does not mean an absence of social conflict but rather sustains antagonistic relationships in a healthy way. Similarly, Bishop stresses that social contradictions or antagonistic relationships, which are often absent in much of ‘community art,’ are a necessary part of good participatory art.16 It is my belief that experiencing some social paradoxes has played a meaningful role in Mixrice’s evolution.

First, there were several migrant workers with whom Mixrice formed long term friendships, establishing solidarity and collaborating on many occasions. After these friends returned to their homes in Nepal, Mixrice visited them to find out what had happened to them. Due to the exorbitant amount of broker fees that migrant workers pay, they tend to overstay their visas, thus remaining separated from their families often for well over ten years and carrying on precarious lives. They avoid getting arrested, and cannot return home even though they miss their families. However, Mixrice was disillusioned when they witnessed the human desire of those who had returned home. Although these workers had been leaders of a social minority group, fighting for migrant workers’ human rights in Korea, back home they wielded power by taking advantage of a kind of social prestige bestowed upon them for having lived in Korea. In addition, even though Mixrice had taken part in demonstrations demanding labor visas, their trips helped the artists realize that labor visas would be inadequate as long as workers’ spouses and children were not allowed to freely enter Korea.17

A second paradox is related to the aforementioned Illegal Lives, a play produced by the Maseok Migrant Theatre, a theatre group founded by migrants working in the furniture factories in Maseok. While Mixrice had led most of the collaborations with the workers, for this play, they contributed only as facilitators. In a way this fact redefined the nature of their collaboration and signaled new possibilities. Moreover, the play included a contradictory social truth, namely, a migrant worker becomes an informant for the immigration office and abuses his status by expropriating portions of the ‘illegal’ workers’ wages. In short, the play incorporated an absurdity of their lives within the host society of Korea.

Third, during the second installment of the Maseok Village Festival, there was a conflict among the migrant workers. The struggle involved two groups of workers who had come to Korea at different times. After the concert the individuals involved reported each other to the authorities and they were deported. Often individuals mired in such conflicts seek the advice of the local Catholic priest, but when workers with legal permits find certain ‘illegal’ workers not to their liking for one reason or another, they may report them in order to have them deported. Even though both the legal and ‘illegal’ groups of workers share similarly precarious lives, it is the workers in the latter group that must be more cautious of their words and actions.

A fourth example may be taken from their experiences in Egypt. As part of the Museum as Hub program arranged by Art Space Pool in Seoul and the New Museum in New York, Mixrice completed a ten-week residency at Townhouse Gallery in Cairo, Egypt. As the cartoon Greetings (2010) depicts, the locals attempted to talk to Jieun Cho by calling out ‘nihao’ and ‘gombangwa’ as she walked down the street; Mixrice realized they had become a social Other the moment they arrived in Cairo.18 In their account, they describe Cairo as a society with a deep-seated envy for the West, i.e., Europe and North America. With the profound gap between haves and have-nots, the poor literally live on top of other people’s graves. Mixrice divulged they could not imagine being there in Egypt other than as tourists, and they described their meetings with migrants and common people as “an uncomfortable encounter among the formerly colonialized.”

In these ways Mixrice has formed solidarity with the social Others; witnessed the Others becoming the powerful; experienced conflicting encounters between the mutually excluded; and recognized the Other within by becoming the social Other themselves. I speculate that after these existential encounters Mixrice may have begun retreating from dialogical aesthetics and interventionist practices grappling with hotly debated social issues and started regarding migration more broadly as a phenomenon. It was during this process that they conducted their research on the history of coerced migrations from Korea to Japan and Southeast Asia.

Parallels in the Work and Life, or Integration Thereof

At times disillusioned by life and at other times distressed by witnessing situations of despair, Mixrice reflected on how to move forward. As part of their solution not only have they connected the inside and outside of institutional boundaries, but they have also founded spaces that are entirely different in character, spaces that are largely free of institutional recognition and career interests. They operate or help operate these spaces, all the while cautioning themselves against becoming an institution of their own.

Mixrice strives to maintain solidarity with not only migrant workers but also fellow Korean artists, neighbors, children, and complete strangers, establishing a platform for interactions and experimenting with new forms of art. In addition to organizing the rock festivals in Maseok, they founded Factory Lights, a space in which migrant workers can produce everyday goods to make profits. Though the space has not generated much profit yet, it is also used to hold workshops for sharing technical shop skills, for community meetings, or simply for hanging out. Along with fellow artists, Mixrice is one of the founding members of Public Art Three Way Junction, a creative labor cooperative. Willow Tree Store is a rundown, former grocery store, which Mixrice acquired for use in an artist residency program. The building now provides affordable shared rooms for young adults. In the town of Goesan, Chungcheong province, Mixrice purchased an old property and built a cinderblock building to house its comic book collection. Known as Goesan Topgol Comics Room, this casual cultural space runs almost ‘automatically.’ It is open 24 hours so that the artists’ friends as well as anyone who finds out about the space through word of mouth or online can visit or volunteer in running it. Finally, Mixrice is part of the collaboratively operated Seongmi Children’s House, funded by Mapo district, and afterschool program “Alkong” where they have been busily involved in offering creative projects that foster curiosity in children, including their own child. These activities require a substantial amount of time, effort, and resources and are to be clearly distinguished from their work as Mixrice. Hence they fall outside the parameters of the institution of art. However, these divergent activities are aligned with the ‘art’ of Mixrice in terms of forming solidarity with the Others, while raising fundamental questions about the system of production and consumption within the capitalist system. Their practice of a sustainable way of life through an emphasis on rest and play is an antidote to the goal-oriented convergent thinking pervasive in our lives.

The Myth of Settlement, or Individuals who Belong Nowhere

Returning from a long detour by having researched migrants in modern Asian history as well as having met migrants in distant places, Mixrice now wonders whether a majority of Koreans might not well be considered another kind of migrant. Heejin Kim correctly observed that the phenomenon of migration is widely viewed as relevant only to specific social minorities, such as migrant workers, and that the issues of “the migratory situation” are increasingly becoming topical, referred to only in relation to racial, political, social, and economical Others.19 In reality, migration has been very much a part of Korean identity in the recent past and present, and that will continue to be the case in the future. It was only 80 years ago when Stalin’s regime forcefully relocated some 180,000 Koreans from the far eastern region of Russia to Kazakhstan. And, South Korea’s remarkable economic growth over the past forty years has only been possible due to tens of thousands of miners and nurses being dispatched to Germany in exchange for economic aid from the German government; workers who took part in construction projects throughout the Arab world; and countless young female workers who migrated from Korea’s rural areas to dilapidated factories in the city. In Mixrice’s view, a significant part of Korean society today is made up of migrants. Through transplanted or destroyed plants, they perceive anxiety and fear as symptoms of development supremacy.

In her book The Republic of Apartments (2007) social geographer Valérie Gelézeau investigates why the apartment as a modern housing structure, which failed in Europe, has become so ‘successful’ in Korea. Unlike the French government, which resolved the issues of public housing for the working class, the Korean government’s housing policy has largely ignored the social underclass and failed to construct long-term rental apartments for its low-income population. Instead, the Korean government teamed up with conglomerates to concentrate efforts on constructing new housing structures for those who could afford them.20 After the collapse of the Whawoo Apartments in 1970, the Dongbu-Ichon-dong complex was successfully developed in 1971 for the incumbent middle class as part of a nationwide economic development plan. By contrast, the Daedanji in what is now Seongnam was a quick fix to accommodate the social underclass en masse. For the latter, the government did not intend to house migrants within a ‘normal environment,’ but rather to turn them into invisible beings who were also subject to exploitation. It is a well-known fact that the major riot in 1971 erupted due to the government’s imposition of an unrealistic schedule for the residents to build their own homes and cough up exorbitant amounts of money as payment for the allotted land. Those excluded in the game of development supremacy and profit generation of the 1970s were best depicted in the novel The Man Who Left Behind Nine Pairs of Shoes by Yoon Heung Gil. Its protagonist, a manual worker with a precarious life who boasts of his college degree, is a synecdoche for many actual, anonymous people. The protagonist represents numerous people who have striven but failed to belong to the middle class, as well as those who have never had a chance to even try. Without fundamental changes in place today, there are men who leave behind a few cellular phones registered under other people’s names.21

The apartment complexes in Korea are the visible results of the preoccupation with quantifiable growth rather than redistribution of wealth. They were built based on a state-initiated ideology of “social happiness” rather than “individual happiness.”22 The principle behind the enthusiasm for the development of apartment complexes in Korea was ‘quantity and speed.’ As such, they were “perfectly incorporated into the [rapid] development supremacy.”23 Most of all, “the instability of urban views in Korea… signify the aggressiveness and speed in the urban transformation. The common trait shared by societies that have experienced rapid development and changes of the territory manifested in terms of blind worship of the new. Hence the prefix ‘shin’ (new) or ‘new’ became widely used without limit,” causing “the deluge of Shindoshi (new city) and Newtown.”24 As every Korean knows, such a phenomenon confirmed that the most important meaning of an apartment was as an object of speculation; apartments functioned as an indispensable mechanism for people to make a profit by buying and selling them, thus enabling them to earn the status of middle class.

Mixrice sees the destruction and “raising” of buildings in such a process in terms of destroying and replacing the traces of time and memory. The interior layouts of apartments in Korea are more or less identical, so the life patterns of the inhabitants are bound to be somewhat similar. Yet many people move to another apartment when it seems as though they are settling down. They move for the reason of investment, or to access a superior school district. Such frequent moves gave rise to the moving contraption that connects onto balcony windows to lift goods up and down outside the building. As artist Seung-wook Koh once mentioned, Koreans have become familiar with the paradox of life in which they endlessly keep “appropriating someone else’s memory as one’s own, or transferring one’s desire unto another’s oblivion.”25 Through such repetition the time and memories of the place are bound to lose some of their specificities.

The anxiety that Mixrice perceives in South Korean society stems from the kind of lives led by the vast majority of people who, despite the remarkable economic growth, have not settled down in a fundamental sense. What appears to be settlement is not a result of free will, but rather due to subservience to the logic of development intertwined with the desire for wealth. Over the past half a century countless Koreans have abandoned their country homes and moved into apartments in the city, symbolic of modernization and advancement of life in Korea. Hence life became a game of moving from a small apartment to a larger one, and the same applied to automobiles, as much as finances allowed. Could one regard such a pattern of life a settlement, where one moves from one mirage to another called an apartment? Settlement connotes physical and psychological rootedness in close association with the earth. Are the lives of Koreans truly connected to the earth? Many Koreans are migrants to the cities, to the destination of their yearnings: modernity. Even though Koreans today are neither exiles nor immigrants, insofar as they do not see themselves belonging anywhere, they may actually be migrants even if they appear to be settled. This viewpoint of Mixrice stems from their recognition of “the limitation of the condition in which the settled regard the migrants, or form solidarity with the migrants from the position of the beneficiary” of the settled.26

Inside and Outside

For quite some time Mixrice has been using the terminology ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ in discussions of their work. What these terms connote have evolved over the years. In the past work, the ‘inside’ within Korean society signified the ethnically homogeneous Korean society and the privileged social class; the ‘outside’ meant the migrant community and its undeveloped, outdated environment of Maseok, which evoked the Korea of the 1970s. In their reflections on the Maseok Dongne Festival, Mixrice stated that they hoped people of the inside, or Koreans, had had an opportunity to learn about certain aspects of Korea through the ‘outside,’ or the migrant community in Maseok. Here the terms inside and outside distinguish the settled from the migrants, Koreans from the foreigners, and recognize the social gap between them. However, due to the limitations mentioned earlier of their position as insiders in regarding the outsiders, Mixrice seems to have changed their approach to art, becoming interested in plants as a universal motif. Establishing a relationship with the Other is fundamentally political and paradoxical. For “One cannot be an ‘I’ without an Other, yet one can’t fully become identical with an Other… Being for the Other is an ethical ideal, absolutely necessary, fundamentally inescapable, and ultimately impossible.”27

Now ‘inside’ means the hegemony of men over nature. The inside is what humans have processed from the raw, and the outside is the object of development and exploitation, i.e., nature and resources, or what men regard as barren. The ‘inside’ means, as it always has, the rights men believe they are entitled to as masters of the earth, and therefore they freely collect, transport, categorize, exhibit, process, sell, and transplant. As Mixrice puts it, the ‘inside’ is “the world in which development and wealth are the subject.” Mixrice raises the questions: “Why can’t we leave the outside as is? Why must we all be inside?” That is, why must we insist on our hegemony over nature? Why can’t we pursue a life beyond the distinction between inside and outside? Their reasoning is not trapped in binary thinking. Rather they are problematizing the fact that the relationships between self and the Other, between men and nature, and between civilization and nature have been defined in binary terms, and that the latter has always been subservient to the former. Mixrice is not simply arguing for nature-friendliness or sustainability.

Plants and Fruits, Time and Memory

Some time ago Mixrice began to adopt plants and fruits as a main motif in their work. What are the reasons for their preoccupation with this theme, despite the risk of binary thinking in considering plants versus apartments, nature versus civilization? During their artist residency at Townhouse Gallery in Egypt in 2010 Mixrice met many other migrants who came to Cairo to achieve a ‘Cairo dream.’ Through their workshop, the artists asked the migrants about things they felt they could not leave without, but were forced to leave behind anyways, which was the same question they had asked migrant workers in Korea. Based on some of the concrete examples in the answers provided, Mixrice made a rain fruit out of agar and placed it on a hand, or somewhat awkwardly hung a pair of mangos from a tree, and photographed them. Presented through a series of photographs, the responses given at the workshop revealed that people remembered sensations unconsciously through their bodies. By evoking the sensate memories of the migrants Mixrice artistically represented the migrants’ experiences without resorting to exploiting their otherness.

During the second Maseok Village Festival in 2013 the fruit sculptures dangled in front of the dark recesses of broken windows in a former factory that was closed down due to a fire. The dangling fruit resembled a dokkaebi’s magic wand,28 or perhaps some sort of deviant life form that had survived a major catastrophe. But these fruit sculptures remind us of Mixrice’s curiosity about migrant workers some fifteen years ago. As something of the unknown, tropical fruits induce curiosity and a desire to taste them. Made out of artificially colored clay, with beans and seeds deposited on their surfaces, these sculptures appeared as though they were looking down upon the gathering of migrant workers and Koreans. Initially Mixrice made these strange fruits while researching the history of migration in Asia. The artists wanted to make unusual fruits of the imagination as they were thinking about the tropics, fantasizing about an encounter with strange fruits in a tropical forest. They represented these brightly colored fruits placed at the roots of local deity trees, thus ambiguously rendering them perhaps as mediums of the deity trees or as offerings to them. Relocated to the burnt factory, these fruits became at once strange creatures but also catalysts for stirring up migrants’ memories.

Most recently, at the conclusion of their residency in Arnhem, the Netherlands, Mixrice also used fruits in their work as a means of eliciting the memories of migrants from Kurdistan and other countries. The collaborative exhibition and related publication involved listening to Arab women who had escaped political strife and could not return home. The women narrated their stories of the fruits they missed, while local children made imagined fruits out of clay, giving them names, describing their taste and smell, and providing brief instructions on how to eat them. As the host of the event, Mixrice offered their audience-participants viscous mixed fruit juice, complete with seeds, exchanged enthusiastic greetings, and most of all, spent time together.

Encountering the fruits remembered by the migrants, or the fruits imagined by the children, evoked the ‘fascination’ that must have been felt by the ‘plant hunters’ who arrived in the colonies several centuries ago. But the plants and fruits conjured by Mixrice had little to do with the violent exploitation of the plant hunters of the colonial era. For Mixrice fruits are strangers, yet they do not merely refer to people. Generating curiosity, the fruits are a medium evoking the memories of migrants who have appeared before us. Indeed, for Mixrice it boils down to the question of memories. The places they pay attention to, such as Maseok, Seongnam, and the specific areas of Jeju Island are where the forsaken people reside. Maseok MDf originated from the resident workers’ wishes to create a memory of Maseok before its radical facelift, for they themselves would leave the city once redevelopment began. As Mixrice stated, “We wished that little bits and pieces of the city, the things that have not yet been institutionalized, could become some form of commemoration and remembrance.”29 While there are transplanted trees in luxurious apartment complexes, there are no trees in Seongnam, a city that came into existence as a result of the state’s reckless housing policy that drove bulldozers over the mountainside. Today in Seongnam there is a concentration of Chinese manual laborers and young women who have migrated from other parts of Asia to marry older Korean laborers; hence, it is a place of alienated memories.

Indeed, an important reason for Mixrice’s preoccupation with trees and plants, motifs that can easily be considered cliché, stems from a certain anxiety surrounding loss of memories. An old tree used to be the center of a village community; thus it was the object of the local belief system, occupying a central place in the common practice of praying and wishing. Such old trees were believed to connect this world with the invisible realm. In both a literal and symbolic sense, trees are the embodiment and recorders of time. Traditionally, trees were considered as bodies of deities, so a ritual would be offered upon the death of a tree. However, nowadays on Jeju Island, deity trees are abandoned among the vines and weeds so it is difficult to even locate them. In the wake of the Four River Project even the villages that evolved along with such trees over long periods of time are now submerged under the water.

Apartment complexes, the new ‘communities’ today, are exclusive ones within a class-based society. While apartments are obviously an object of desire and a prime method of investment, trees are now in servitude to increasing their values. A thousand-year-old tree that used to be located on land that is now underwater at Gunwi Dam in North Gyeongsang Province is now part of the landscaping at the Banpo and Dongcheon apartment complex. Severed from the actual historical narratives of “the weight and distance of a thousand years,” trees have become mere decoration for stacks of housing units built on standardized designs on a quantified plot of land. In his book Noise, a treatise on the evolving history of music, Jacques Attali recounts how music was once a communal experience, shared as part of a ritual within the space of a community; in the eighteenth century people started paying to enter a confined space where they consumed music along with others; in the past century a new era arrived wherein each individual consumes music in solitude with a headset.30 Similarly, deity trees once considered sacred are now transplanted inside the exclusive space of an apartment complex, and the owner-residents consume the old trees as a symbolic presence that complements the class distinction and renown of their apartment as a commodity brand. In short, transplanted trees are a means of consuming history, time, and civilization. The old trees perform the duty of advertising the apartment complex as an object of envy, making themselves visible for those who desire to become part of the complex. In this way, some decontextualized traditions can be seductive at times.

Tracing a Pattern of Time: Toward the Outside

Mixrice examines how the traces of migration are remembered and how they can be represented. While people have always migrated from one place to another in search of a better life, how much do we know about it? To what extent do we face the concrete realities of migration? The phenomenon of migration is rooted in desire. No one can criticize the human desire to live a better life. However, that desire inevitably faces issues arising from encounters with capital, borders, institutions, family, memories, and time. Mixrice has been present at these intersections along with the migrants. The work of Mixrice mourns the memories of the communities and the stories of individual lives lost in the midst of development, and for the devouring of time in the master narrative of profiteering.

Works in this exhibition show the ways in which trees, as a symbol of migration, have been used as a means of supporting the desire of the middle class in the history of modern Korea. It is imperative to remember that when transplanting a tree from the countryside to an urban apartment complex, changes occur not only to the tree itself, but also to the entire ecosystem that depends on that tree. The death of a tree from cutting or uprooting is not merely the death of the tree itself. Although mostly invisible to the naked eye, associated with a tree during its lifecycle are endless chemical reactions in the atmosphere, the lives of parasitic microorganisms such as fungi, bacteria, and microbes, and a myriad of insects, birds, and animals. Thus the death of a tree ruins time and also ruins a small universe that evolves in time, independently of the human race. Trees and plants, hence, are an embodiment of vibrant vitality; they are sonorous, reverberant, and resonant objects emitting energy.31

By contrast, seen from a biological perspective, all of humanity is at once a part of nature yet strangers. Would it be an exaggeration to say that humans are like horsehair worms in the sense that they only exploit and cause harm to nature? “The horsehair worm’s relationship with its host is entirely exploitative. Its victims receive no hidden benefit or compensation for their suffering.”32 Of course, nature is man’s host. As Mixrice stated, our outside, nature, is our eternal Other, subject to our endless colonization and exploitation. Their interest in the potential of vines is an expression of their will to coexist with the Other called nature.

Biologist David George Haskell, author of the celebrated book The Forest Unseen, watched everything he possibly could within a designated plot of land measuring about one square meter on a hillside in Tennessee for a year. His observations involved not only the small piece of land itself but also all the animals, plants, and organisms he encountered at the site. At the conclusion of the year Haskell reflected as follows: “I have understood in some deep place that I am unnecessary here, as is all humanity. There is loneliness in this realization, poignancy in my irrelevance…. The world does not center on me or on my species. The causal center of the natural world is a place that humans had no part in making. Life transcends us. It directs our gaze outward.”33 Although humans are “strangers and kin” on the earth, we must take note that Haskell classifies men on the outside of nature, and calls for men to direct “our gaze outward.”34 The “outward” that Haskell refers to is not unlike the “outside” Mixrice has been referring to all along.

By taking a step backward from collaborating with migrant workers Mixrice looks at the reality of migration. Let us take one step further back and consider their activities in the context of global realities. Their interest in trees, plants, and fruit, their critical gaze at apartment complexes and middle class culture, and all the concurrent non-profit organizations and various creative activities associated with the Topgol Comics Room in Goesan, Factory Light in Maseok, Public Art Three Way Junction, Willow Tree Store, and the afterschool place for children “Alkong” are small movements towards a converging point of “the conjugation, at local and planetary levels, of non-capitalist modes of survival with strategies for the revolutionary construction of post capitalist society.”35 Humans, as “strangers and kin” of the earth, are now to move beyond “the materiality of desire”36 and humbly resume the observation of plants, the quintessential model of “cooperative action,”37 and learn from plants about life on the outside.