Song Sanghee

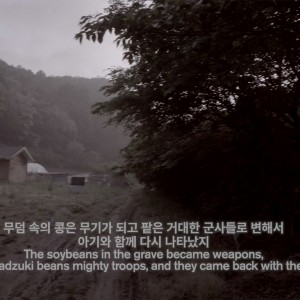

Song’s new work Come Back Alive Baby deals with the end of the world, salvation, apocalyptic condition and the energy of new formation based on the folk tale of “a baby commander”, a tragic hero story. Through video, drawing, and text, she presents variations of “a new life force” rising even from the extreme situations of despair and extinction such as one in which individuals are sacrificed for the stability of a country or a group; a great famine and the bankruptcy of a local government; ruins due to the worst nuclear power plant accident in history. On the opposite side is This is the way the world ends not with a bang but a whimper, created with a collection of countless explosion images. In this way, the artist juxtaposes the “The Hollow Men” who are accustomed to living in the face of the ongoing reality of catastrophe and the crisis of humankind’s co-destruction.

Interview

CV

<Selected Solo Exhibitions>

2015 The story of Byeongangsoe 2015, Art Space Pool, Seoul, Korea

2015 ‘O’ VZL Contemporary Art, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

2014 Peace to all people in the world, Chongching artcenter, Chongching, China

2004 Blue hope, Insa art center, Seoul, Korea

2003 mangbusuk 望夫石, Freespace PRAHA, Sapporo, Hokkaido, Japan

2001 Machines, alternative space pool, Seoul, Korea

<Selected Group Exhibitions>

2017 Korea Artist Prize 2017, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea

2016 Aichi triennale, Nagoya City art Museum, Nagoya, Japan

2014 The 4th Anyang Public Art Project, Anyang Pavilion, Kim Chung Up Museum, Anyang, Korea

2014 Good Morning, Mr. Orwell 2014, Nam June Paik Art center, Yongin, Korea

2013 De presentaties van de genomineerden Workspace Filmhuis, Filmhuis Den Haag, Den Haag, The Netherlands

2013 Tireless Refrain, Nam June Paik Art Center, Yongin, Korea

2012 The mechanical cocoon, Arti et amicitiae, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

2011 City Net Asia, Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

2010 Women Make Waves Film Festival, Taipei, Taiwan

2010 The 12th International Films Festival in Seoul, Seoul, Korea

2009 Finding Korea, Sinn Leffers, Hannover, Germany

2008 El Punto del Compás, Sala de Arte publico Siqueires, Mexico city, Mexico

2008 BIENNALE CUVEE & FESTIVAL, OK Center, Linz, Austria

2007 TransPOP: Korea Vietnam Remix, ARKO Art Center, Seoul, Korea /Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco, USA

2007 Global Feminisms, Brooklyn Museum, New York, U.S.A.

2006 The 27th Bienal de São Paulo, How to live together, Porão das Artes Pavilhão da Bienal, São Paulo, Brazil

2006 The 6th Gwangju Biennale, Biennale Hall, Jungoei Park, Gwangju, Korea

2006 ArtSpectrum 2006, Leeum Samsung Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

2005 The Battle of Visions-Critical Art in Korea, Kunsthalle Darmstadt, Darmstadt, Germany

2004 Busan Biennale, Busan Metropolitan Art Museum, Busan, Korea

2004 Stepping Across Borders, Hokkaido Museum of Modern Art, Sapporo, Japan

<Collection>

Wumin Art Center, Korea

Art Council Korea, Korea

National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea

Seoul Museum of Art, Korea

<Awards>

2008 Hermès Foundation Missulsang, Korea

<Residency>

2015 Okinawa Creator Village, Okinawa-si, Japan

2012 Warm Heart Art Tanzania, Arusha, Tanzania

2010 Aomori Comtemporary Art Centre, Aomori, Japan

2006-2007 Rijksakademie van beeldende kunsten, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

2005 The 7th Ssamzie Artist Residency Program, Seoul, Korea

2003 Sapporo Artist in Residence, Sapporo, Japan

Critic 1

Beck Jeesook (Art critic, curator)

Song Sanghee is an artist who exemplifies the growth and development of Korean art venues since the 2000s. Around the turn of the millennium, Song took part in various activities at alternative art spaces, which were then beginning to flourish, helping to reinterpret the legacy of Minjung art (or “People’s art”) and feminist art. She soon began gaining renown for her agile experimentations with important topics and practices that reflected the development of Korean art, such as the emergence of public art, works based on archive analysis and research, and projects that combined performance and media. By the 2000s, many artists who had studied abroad were returning to Korea, and they helped to transform the infrastructure of Korean art by emphasizing artistic expertise and asserting the need for a public system supporting such expertise. Through the course of this development, Song Sanghee has been one of the few Korean artists with no international education who has been invited to join publicly funded exhibitions and residence programs, both at home and in other countries. As such, she has traveled through Korea and other countries, participating in residency programs and creating diverse works.

Most of her early works were very dense compositions examining the relationship between the body (flesh or corporeal entity) and history, society, memory, and emotion. But since establishing herself in Amsterdam in 2006 (after being invited to a residency program of the Rijksakademie), she has greatly expanded her topics and the overall scope of her artwork. Unfortunately, however, some projects that she spent considerable time planning and researching have fallen through due to a lack of financing or support. With 2016 marking the tenth anniversary of Song Sanghee’s relocation to Amsterdam, the time seems right to revisit some of these projects. With the public support of the Korean art world, Song can finally bring these projects to fruition so that her exceptional artistry can be seen from a new perspective.

Both Korean and international critics have interviewed Song and written in-depth about her various works. However, one important early work that has not been adequately covered is Cleaning (2002), which may be seen as a seed that contains her fundamental artistic attitude and interest. Cleaning is a performance work, wherein Song wore an outfit of black leotards covered with adhesive tape, and then used the sticky surface of the tape to collect dust that had settled in the corners of Korean middle-class homes. With this performance, she caricaturized her (political) identity, but also made it into a fable, while highlighting her own self-sacrifice and degradation. As viewers quietly observe the honesty and earnestness of her postures and movements, they are forced to rethink emotions such as shame, anxiety, and discomfort, resulting in a type of psycho-therapy. The ultimate effect is an increasing will to face the truth. This effect is elicited even more dramatically in other works, when Song performs as the protagonists of myths, heroes of the people, or victims of historical events.

Although they often address monumental events and people, Song’s works are never saturated with the conventional meaning inherent to monumentality. Instead, they generate heterogeneous textures. Since 2010, as she has infiltrated the history and culture of Europe, Africa, and East Asia, her narratives have become more complicated and her apparatus for developing them has become more elaborate. To create multi-layered performance works that tell various stories, she has increased the depth and duration of her preliminary research, conducting interviews and reviewing literature. Accordingly, her media has been diversified and mobilized, even allowing for custom- or self-made media. She is particularly fascinated with storytelling techniques borrowed from popular culture, such as heroic stories, legends, espionage, and science fiction. In some cases, these techniques are concealed within the internal structure of her works, while in other cases, they are intentionally exaggerated. On the surface, they are loosely connected through the fragmentary characteristics of montage, but they also show an emotional consistency that emerges from the powerful tones of music and color. Having recognized the complexity of her topics of choice, she pursues them through labyrinths where suppressed states of awareness returned. In the end, the largest monument that she has constructed is a memorial to death. Whether it commemorates the death of an individual, a group, or the earth, she has built this memorial through her sensitive empathy, strong ethics, and first-hand chiseling of reality. Under the light of art, Song Sanghee reveals the darkest continent that our society has thus far refused to face.

Critic 2

Ahn Sohyun (Independent Curator)

Song Sanghee’s works are characterized by the coexistence of contrasting images and elements. On the one hand, Song identifies and comforts oppressed or weakened people, especially women and children, who have been victimized by history, patriarchal power, war, colonialism, or capital. At the same time, she criticizes our entrenched ideologies, contemporary myths, and dominant power. Thus, her works combine the delicacy required to sooth vulnerable people and the grotesqueness required to depict the ruthless and prodigious power.

Around 2009, Song began using photos and other media to satirize the forced lives of women. In Evening Primrose, for example, she collected poems written by female sex workers in Amsterdam, and then projected the poems onto the city’s Red Light District. With each subsequent narrative, she carefully determined the proper media and communication methods for the situation, such that her compositions have become denser and more complex. Metamorphoses Vol. 16 is an animation work that expands upon the Greek myths of Ovid, telling a love story between imaginary individuals that incorporates references to ecological destruction, oil money, and state power. For another work, she presented her personal collection of items acquired at flea markets (e.g., postcards, uranium glass bowls, dry flowers), using these miscellaneous goods to distill the manmade tragedies of environmental destruction, biological extinction, and problems of nuclear energy. She has also composed radio programs of songs that press down on the listener with the heavy weight of ideology and created drawings and videos that represent tragic scenes from history. One of the most powerful examples is Shoes, in which she shot endless video footage of shoes floating in the ocean, representing the aftermath of the disaster of Korean Air Lines 007, which was shot down in 1983.

Song Sanghee’s methods of collection and invocation have been strengthened and enriched in increasingly complex installations that combine text, music, videos, and drawings. In That Dawn, Anyang: People Dreaming of Utopia, she combined scenes from a real Korean city whose name (Anyang) means “paradise” with texts, drawings, and music depicting dystopia or the collapsed utopian dream. For her 2016 solo exhibition, as well as the 2016 Aichi Triennale, she added more layers to this technique to create Song of Byeon Gangsoe: Looking for People, which might be called a “video-opera.” At various sites of historical tragedies, Song projected drawings of the victims of those tragedies, such as war prisoners and comfort women. She filmed the entire process, adding dialogue from the victims, who have often been perceived as coarse or common. This unfamiliar rite of invocation is again led to more recent and ongoing tragedies, such as the sinking of the Sewol ferry and the refugee crisis in the Mediterranean.

Some might claim that such multi-layered and complex works are difficult to bear, making them an inefficient way to address these tragic episodes. But in their purest state, these works embody Song’s continuous efforts to reveal the never-ending series of “ordinary” tragedies that accumulate every day, taking the lives of untold numbers of victims without investigations or condolences. In this day and age, as we are becoming increasingly desensitized to the pain of others, Song Sanghee refuses to overlook any possible way of awakening our sense of pain. The result may be uncomfortable, and yet we cannot take our eyes off this uncomfortable beauty.

Critic 3

Caressing The Skin of History

Beck Jeesook (Art critic, curator)

The Past of the Artwork: Reading Through Dialectic Images

In a past interview, Song Sanghee spoke about her “desire to stand up straight on a spot, something like a blade of a knife.”1 Her works were then engaging with a sharp identity politics as a non-disabled heterosexual woman from South Korea. As I observed the two edges of her blade transform into a daughter and a mother2, a prostitute and a classy lady3, the first lady and Yeongja4, and later into a missionary and indigenous people,5 I was picturing the artist perilously standing on a blade each and every time.

In her performance of the typical two edges that constitute cultural systems—tradition and modernity, colonialism and globalization, the divine and the secular, the normal and abnormal— Song Sanghee seems to be less following a given role than she is following an acting technique that threatens the system and discourse by embodying typicality. Perhaps she is so dedicated to the roles, to the point of becoming one with each of them, that the artist overwhelms the character—like Do Kum-bong did in Yun Bong-chun’s 1959 film Yu Gwan-sun, where she portrayed the Korean Jeanne d’Arc who sacrificed herself for the liberation of her people. The physicality of the actress, notably standing out during torture scenes, overwhelms the March 1st Independence Movement’s historicity and transmutes a typical nationalist film into a bizarre horror movie. Likewise, Song’s performance of the first lady’s tears and Yeongja’s smile penetrates through the symbolism of motherly love and diligence, spookily summoning the sacrifice, or even the revengeful spirit, of the female oppressed by dictatorship and state-led economic development. Here, the first lady and Yeongja are not separate characters but rather multiple personalities hiding within the same body, which are manifest according to social conditions and specific situations; any control that prevents total breakdown belongs solely to the artist (or to oneself who identifies with the artist). In other words, Song’s blade fractures the collective memory and official history imposed by the nation-state onto the individual and reveals mental traumas and personal secrets engraved on and hidden in the individual body.6

Meanwhile, the locations of the photographs—Wolmido, Maehyang-ri, Dongducheon—are parts of Korean territory that the U.S. military either attacked or was stationed at, sometimes bringing Korea’s identity as a nation state into a crisis. In the event-based system (as opposed to structure-based) of this photographic world, the human body serves as an element of the social landscape. For instance, the missing arm in Blue Hope, the marks of arrows that hit young girls in Maehang-ri, as well as the black tape over the woman’s eyes and mouth in Dongduchun, compose the scene like fingerprints left on a victim’s body do. In terms of geopolitical landscape, this is both a terrain bearing traces of the patriarchal state and an empty lot signaling the absence of sovereignty. The mise-en-scène of identity, constructed through inner oppression and outer exclusion, quickly crumbles in a national territory occupied by international superpowers; instead, a mise-en-abîme takes place that both oppresses and excludes the interior, resulting in an endless void created by self-confronting and self-reflecting national images. Mirage, a mid-air installation of Gwanggaeto Stele made of plastic wrap, appears to be an empty and rebellious memorial to the modern national identity in this context.

The Future of the Void: Reading Through Rhetoric

This is perhaps why Song Sanghee confesses that she “believed [she] can stand up on any place. But . . . it may well be that [she has] been floating in a void.”7 Once dancing between blades and the void, the artist now attempts to levitate. The weakening of national identities by intensified international political dynamics dislocates gender politics in the process, providing Song Sanghee with a chance to “rise up” to the international level.8 The further she floats above the blade of identity politics, the larger the void captured by nation-state ideology; a transnationalist mythology unfolds in a global perspective, beyond a single nation’s territory and airspace.

Evening Primrose, Song’s 2006 project during an artist residency in Amsterdam, Netherlands, was initiated as poems written by sex workers were shared through the network of the International Union of Sex Workers and other related organizations. The poems were projected using lights installed above the walls of a church in the middle of the Red Light District in Amsterdam; passersby and sex buyers could read the light-poem projected on the sidewalk. Light and poetry here, as media that cut across the red dark, effectively carry the individual sensitivity and character of each woman who wrote the poems—instead of objectifying or generalizing sex workers. The artist emotionally connected with them, gaining self-awareness as a connected being within a certain world.9 Fittingly to its title, Evening Primrose came to an end during the night after a sex worker, discomforted by the unusual brightness, asked to have it taken down. For Song Sanghee, who delicately coordinated the project since its conception, the project’s abrupt halt was most likely an opportunity to contemplate more radically on the artist’s relation to others in the world.

With the residency over, Song Sanghee decided to relocate abroad. Unlike younger generations who supposedly leave Korea for their “contempt towards Hell Joseon,”10 she belongs to the last generation that experienced the steady political and economic developments of post-war South Korea. Also, unlike older generations, she belongs to the first generation of artists that benefited from a systematic and accumulated cultural education as well as a growth of public funding towards the arts. Immigration for Song Sanghee must have meant more of an opportunity to become a better person. I imagine her decision was made in order to secure personal freedom and independence as an unmarried woman who grew up in South Korea’s compressed mixture of pre-modernity and postmodernity, as well as to connect directly with a more open knowledge and flexible technology as an artist. Around this time, Song Sanghee went through a complex self-verification and efforts for adjustment that she has to confront as “part of the emancipation of the fleeing non-western artists,”11 attempting multiple artistic projects that oscillate between skepticism and reckless courage. She even dies an early death. Rather than the guilt of a rebellious patriot who ends up turning her back to her country, or the shame of leaving one’s family and friends behind,12 Song Sanghee willingly embraces near-death experience in Her funeral (2006) and Ready to die (2006). The year she applied for permanent residency in Netherlands, she completed The 16th book of Metamorphoses (Metamorphoses, 2008). This work led Song Sanghee to be regarded as epitomizing the complex identity of the artist in general, which is closely tied to the larger network of identities within diverse social realities, in the context of post-colonialist cultural politics.13

The biggest change observed in Metamorphoses is that the artist goes beyond dismantling the existing system and rigid typicality, moving towards weaving new textual narratives. The piece’s protagonist is an asexual creature that morphs between human and animal, between living and object, traveling across Ovid’s Greek and Roman mythology and the Bible, creationism and evolution, sciences and fables, and historical events and allegorical spaces. The blinded and muted female character from Dongduchun starts expressing thoughts and emotions in Evening Primrose, before eventually obtaining a voice of its own as the narrator of Metamorphoses. The voice follows tragic protagonists who are murdered, kill themselves, and finally self-destruct along with the Earth, before giving way to whale sounds in the end credits; it maintains a prudent and considerate, yet hesitant tone. The narration here does not reduce the polymorphic creatures into the single voice of the artist, nor does it take an omniscient and objective perspective. The protagonists pursue love and revenge while being precariously swayed by war, cannibalism, self-replication and sonar systems; they are fully exposed to the instability and vulnerability of contemporary life, closely tied with capitalism, military industry, and financial networks. The artist’s voice is but a receptacle of such feelings.14

The pencil-drawn animation lively illustrates the main theme—metamorphosis—before ending on the Earth being catastrophically covered by oil. The 2010 blowout in the Gulf of Mexico of the Deepwater Horizon, owned by the multinational oil and gas company as well as oil flooding forerunner BP, remains one of the worst recorded disasters on the marine ecosystem, along with the Samsung-owned Hebei Spirit’s oil spill in Taean, an accident addressed in Song’s Mohang (2008).15 The massive amount of spilled oil devastates not only natural environment but also the very human existence and modes of perception. Faced with the boundless ocean covered with sticky black oil, we realize that the end is nigh. Ecological theorist Timothy Morton writes that oil allowed us to “[burn] a hole in the notion of world.”16 In a world where the scale and impact of disasters have surpassed the capacity of any single nation, and the post-Anthropocene acceleration of Earth’s destruction is beyond control, ecology is much more than just natural environment. Global warming, ultrafine dust, radioactive waste, and sonic weapons spread like invisible toxic gas, not only altering a wide range of relations but eventually disabling the human subject’s perception of the world. Hyperobjects that stick to, penetrate, and coat the subject with their oil-like viscosity, reveal that “[i]t’s not reality but the subject that dissolves, the very capacity to ‘mirror’ things, to be separate from the world like someone looking at a reflection in a mirror.”17

For the Korea Artist Prize 2017, Song Sanghee installed two flat pieces at opposing sides of an empty space that is larger than 20 meters in every direction. First of all, this empty and deserted space is significant. Some of Song’s works are, in fact, large and empty.18 The importance of void in her work relates to the size of the piece: the bigger, the emptier. While this might invite an environmental interpretation on material, or be seen as a feminist parody on size, it seems more than anything that Song Sanghee attempts to compose the void. The bleak and desolate atmosphere of the exhibition space presents a fast-forwarded post-apocalypse to our senses—in a Korean peninsula threatened by an unprecedented US-North Korea nuclear crisis. So reemerges the distance between the world and I—the relationship between a world-reflecting artwork and I, which had once vanished in the era of viscosity.

Come Back Alive Baby

Song Sanghee explains that the protagonist’s name in Metamorphoses, Khora, comes from Plato’s notion of khôra, which designates a receptacle of being. Khôra is a space that was already formed before the very first matter was composed. It is neither existence nor creation, form nor imitation, being nor nonbeing; it is a space in-between. Moreover, khôra is a receptacle as well as a stomach and a womb; rather than merely being an empty recipient that can only be shaped by matter, it wields a certain power to distinguish and arrange incoming objects and to attribute heterogeneous motility.19 In Metamorphoses, Khora was a creature that transformed constantly by eating and being eaten; at the same time, it only existed through this relationship. In this exhibition, Khora transforms into a “nurse (tithēnē)-like”20 space which nourishes the post-apocalyptic ecology and brings it to creation; the space embraces the baby and brings it back to life.

- An Intermedia Mosaic

Come Back Alive Baby (Baby, 2017) takes as motif the Agijangsu (“Mighty Baby”) tale, a Korean folk legend which revolves around loops of birth and death, revolt and suppression, massacre and resurrection. Similar in format to Anyang at the Dawn of the Day, The City Dreaming of a Utopia (Anyang, 2014) and The Story of Byeongangsoe 2015: In Search of Humanity (Byeongangsoe, 2015),21 its montage of archival film, documentary videos and photos, staged footage, pencil drawings, text, and sound attests to the establishment of a certain visual grammar. Anyang mainly consists of documentary videos of the city’s nightscape with minimal movements or events. While the modern industrial city’s name means a utopian space where all can rest comfortably, Anyang in Song Sanghee’s 2014 piece is set up as a post-nuclear explosion society of the future; Anyang functions as science fiction by exposing the dystopia that is already here. Two scrolls of pencil drawing hung next to the screen, partially highlighted by moving head multicolor lights that are synced with the video, contribute to the piece’s kaleidoscopic diversity. Byeongangsoe, completed the next year, is an installation which involves three monitors of different sizes and a projection screen that display videos and text, while moving spotlights illuminate different parts of the exhibition space. The work is seen as a multilayered video opera which adapts the iconic and classic Korean pornographic tale of Byeon Gang-soe and Ong-nyeo into a corpse trading story.22 This is likely due to the images and text densely compressed into each channel, reminding one of an opera stage where chapters are led by a monitor-prima donna. In contrast, Baby keeps the large and empty screening space as its constitutive outside and incorporates drawings and spotlights into its three video channels, maintaining genre conventions of essay films.

In the three works, Song Sanghee connects and arranges images of different textures, inviting a heterogeneous spatiotemporal intermedia experience. This experience, synchronized with technologies that borrow from and transform conventions of the genre,23 helps to bootstrap historical orientation and sensibility. In Baby, archival material is carved onto an intermedia mosaic as its principal pattern. The compilation of archival footage and photos from around the world mostly consists of documentations of horrible events committed by state powers such as fabricated espionage cases, famines, and concentration camps. We tend to think of these historic events as familiar. However, when montaged together with other images, text, and sound within the piece, the archival image clips notably stand out; the indices were created through direct contact with the historical event. Archival photos of the East Berlin Case, that seem to be developed in real time, come across as more tactual, than visual, facts. Re-recorded footages of documentary monitor screens in the Ukrainian National Chernobyl Museum are less historical indices than they are real cinematic objects that touch and react with our present body. The large eggs on the beach in Ouddorp or the giant mutant catfish in Chernobyl’s cooling pond, projected on the other screens, are other organisms/environments that induce this interaction.

- Hyper-Archival Impulse

A sequential review of the three formally similar pieces reveals that the archive is not only a component of these works but also a cinematic device that leads to a creative and ethical confrontation of the real. In this complex representation process of history and memory, the artistic mnemonics required from the attentive observer is activated as well. The three pieces could be called an archival trilogy, respectively emphasizing and cycling through the future, past, and present. Anyang‘s mechanic and cold documentation of a dystopian future not only is an early record of the post-apocalypse but also leaves the city of Anyang as an archive for the future. The following year’s Byeongangsoe archives the deaths of homo sacer, pervasive throughout East Asia from the 19th to 21st centuries. Notably, it establishes a non-chronological, yet almost compulsive, death archive. This piece, along with drawings of victims’ faces and mid-air installations of empty scarves that chant The Story of a Desperate Lady, transforms Art Space Pool, with its exposed walls and ceiling, into an archival space for Gothic summoning. The artist states that the idea for Byeongangsoe came at a period of collective depression and lethargy in South Korea, following the Sewol sinking disaster. As the aftermath of the horrific man-made disaster stuck to one’s skin like the epidemics mentioned in the piece, the stubbornly material and fragmented structure of the archive is none but the symptom resulting from an existential shock and the artist’s responsibility.24 Meanwhile, Baby, the last piece of the trilogy which was shown after the Korean “candlelight revolution,” is filled with the present. Eggs roll around a scifi-esque beach, next to photos of victims of the Committee for Re-establishment of the People’s Revolutionary Party Incident; an interview of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the father of the atomic bomb, is juxtaposed with landscapes of Pripyat, Ukraine; dolmens and drawings of babies’ hands from around the world are put one next to another. The past archive, rather than being an absolute origin, provides vague clues to pursue; the documentary scenes and staged footage constantly flow towards the future, as yet unfinished projects without ampliative meanings.

Debates over the objectivity of historical accounts and the historical-philosophical questions involved in the selection, categorization, and accumulation of records also apply to the hierarchy of knowledge and information that constitute the archive. The fact that archival films have greatly increased after the World Wars point to the inevitability of confronting key issues of ethics and aesthetic power as one attempts to document death using film.25 Accordingly, any work that attempts to collect ‘the deaths left in the field’ by modernity (and its archive)—such as war, genocide, famine, human experimentation, and epidemics—necessarily demands a perspective and stance regarding the archive as an institution. Artists faced with such challenge often emphasize poetic approaches and metonymy while exploring fantasies and the unconscious, in order to deconstruct the existing archives and archival ideologies; in this sense, they have strong anti-archival tendencies. Furthermore, Song’s archival works eventually engender counter-memory, as the candle in Baby, invoking people abandoned by the state power, symbolizes. Her archive can be described as a nurse-khôra which nurtures and embraces “orphaned” films.26 More than anything, Song’s archival pieces firmly reject the nostalgic kitschification of the archive, or an abstraction which overlooks relevance for the sake of formal beauty. Instead, the artist chooses to exaggeratedly expose the existence of the archive, through a disorderly, unsystematic, and random over-accumulation. Hence her creation of a hyper-archival situation by tenaciously overlapping unfamiliar images, poetic text and solemn sounds over existing archives. While this is an allusion to the contemporary media environment where one supposedly no longer needs to shoot any new images, it is also a reaction to the Korean history which is void of any archive at all.27

- One Image, Two Skins28

The first image that appears on the middle screen of Baby‘s three-channel video installation is a glossy tile floor. Decorated and rough brick walls follow, while the two screens on the side show barren land, gravels, dusty roads, and such. The index printout indicates that all the locations are related to massacres or other tragedies. As Song Sanghee visited these places to film them, the world-historical scenes were not merely places with traces of past events, but rather living skins of history.29 All skins of history have wounds, especially when we read literally the ending scene where a hand caresses the burnt skin of another hand.

In André Bazin’s definition of film as the skin of history, the important part was less the skin itself but the wound revealed as the skin tore; the wound would be what reveals the true skin of history, the factual flesh and bones concealed under the surface of the film. Documentary footages that make up most archival films play back the skin of history, thanks to cameras everywhere and even more screens, but “[a]s soon as it forms, History’s skin peels off again.” On the other hand, by ripping archival footage out of its original fabric and reassembling it into a new film of the present, we are confronted with a previously unconceived reality of history. The second skin, created by wounding the ever-peeling skin of history, emits a certain aura. This aura allows one to sense the other strange and unintended meaning, which has always existed behind the surface of the original subject.

For instance, let us consider the footage of a baby farm where Nazis led racial crossbreeding experiments. The image of the babies and the pretty baby as described in the Agijangsu tale, displayed textually, are severely disparate; the wiggling lives are juxtaposed with drawings of insects, which emphasizes the stubbornness of reproduction. Ironically, as the on-screen movement intensifies, the living creatures only emit a corpse-like strangeness. The wiggling babies create wounds which reveal deaths that are not portrayed on the screen; from the revealed true skin emerge massacres in Auschwitz, murders of disabled babies in crossbreeding experiments, and the killing of refugees on a boat. Then we return to the textual surface, only to be faced with the wings of Mighty Baby, born “abnormal” and repeatedly killed by its parents. The superimposed images ask: Are we not men?

If a cut is literally a wound on a film, an editing that reveals the relationship between coincidence and reality can develop the signification of wounds beneath the skin-image more radically. Baby is an essay film written on three screens. While three-channel films are not uncommon in contemporary exhibition spaces, a notable thing about this piece is its maximized horizontal field of view, stretched across screens separated by gutter-cuts. Tilt shots taken by the artist create movement on the side screens; one needs to look left and right between text and image in order to read the essay film. The heterogeneous textures of images, text, sound, and black- and white-outs are assembled through a “horizontal” montage “as opposed to traditional montage that plays with the sense of duration through the relationship of shot to shot.”30 Baby juxtaposes images that ventriloquize notions and theories in a lateral expansion of time-space. This editing rhythm eventually turns Baby‘s semantic structure into a sort of complex network, open in all directions and all dimensions.

The eggs laid on the beach in Ouddorp is reminiscent of legends of egg-born babies. As the eggs, once alive and moving, are stacked onto a cart with plants growing all over them, their meaning diverges. Juxtaposed with unjustly killed souls, the scene appears to depict a bier sending off babies that did not hatch. As the white round eggs transition into circular patterns, which transform successively into bullet marks on a wall, eyespots on butterfly wings, cuckoo eggs, algae cells, and then again into beans described in the text. This sequence leads one to think that the plants thickening over the eggs may be a life-image that summarizes this cycle of creation. Moreover, the circular patterns that repeatedly enter the screen seem to serve as a memorial symbolizing the self-sustaining elasticity of the archive, in which “[w]hat’s known [as existing, happening, or problematic] but ignored takes its revenge.”31 Or perhaps the eggs are empty, temporal buoys which inform the rhythm of horizontal editing.

This is the way the world ends / Not with a bang but a whimper

Baby and This is the way the world ends / Not with a bang but a whimper (This is the way, 2017), which are installed more than 20 meters apart, are connected via sound. As Baby‘s video installation approaches the end, and one follows distant sounds until reaching a tile-wall, unfamiliar speeches come out of intermittently installed speakers: greetings in 55 different languages that were included in the Golden Record sent along with the Voyager unmanned solar system probe, played back through the Google text-to-speech system. As this sound crossfades with The Song of Earth played back on Baby‘s screen and creates the soundscape of the empty space, blinking speaker lights seem to communicate with other speakers or with us, like satellites. The machine-produced broken Korean is strange and bizarre, as one would expect of earthly sounds that returned from space.

Tiles used as interior material are ordinary and familiar, like greetings would be. But when linked with music by Isang Yun, the Korean-born German composer who was imprisoned during the East Berlin Case, a fabricated espionage case, which returns us to Baby‘s footage, This is the way‘s tile wall obtains a whole new meaning. Holes in the wall and scratches across bed surface tiles of the human experimentation lab causes historical wounds to the giant smooth tile wall, as one comprehends that domestic tiles have also been used to cover the walls of laboratories and torture chambers. A close look reveals that the drawings on Delft Blue tiles are processed images of explosion scenes, familiar to us through mass media. Delft pottery, which was localized in the Netherlands based on Chinese porcelain, seems at first glance to attest to a rich and stable life. But once the deadly and fearsome exterior scenery is projected onto the interior wall, This is the way becomes a trigger that enlightens our reason, desensitized to violence. The tile wall is hence another second skin, which protects yet easily breaks; hides yet reveals; and connects yet peels off immediately.

This is the way belongs, in some sense, to Song Sanghee’s series of archival works. The drawings printed on the grid of tiles distills the history of Sino-Dutch trade, while hinting at the intersection of religious and monochrome paintings. On top of this are overlaid images of explosion collected from different periods and areas, from atomic mushrooms from 1945 to clouds caused by airstrikes of ISIS. Like the bath-archive discovered in France after World War II,32 This is a way‘s tile-made sound archive bears the contradiction and irony of simultaneous preservation and destruction. For instance, as voices extracted from the earthly archive that is the Golden Record pass through Google’s archive, it becomes clear that defunct languages are preserved on the record. Meanwhile, one realizes that the knowledge, information, and data once monopolized and distorted by superpowers during the Space age are now even more explosively modified and processed by transnational companies in this globalized age. Faced with the skin surface of history, where screen and monitors montage images of violence over a saturated Earth, I begin to doubt: perhaps these images are, as if confined within smooth tile walls, merely assembled together without a bang.

The title of this piece comes from the last line of The Hollow Men by T. S. Eliot. The poem, written while Europe was in flames due to World War I, was also quoted in Chris Marker’s digital image piece of the early 21st century along with incessant explosive sounds.33 In Song Sanghee’s piece, The Hollow Men is connected once again, this time with soundless images of explosions that cover the Earth. The skin of history only keeps being revealed as one follows with sensitivity and sincerity the relation of art and the world. In order to conceal this skin, Song Sanghee chooses to rely neither on leaves nor on leather. Instead, she covers herself with double-sided transparent tape.34 She then rolls her entire body and meticulously collects the dust, produced by explosions and covering the Earth, using her sticky second skin.