Sojung Jun

Sojung Jun has worked in a variety of media, including video, sound, sculpture, installation, performance, and books. In her solo exhibitions As You Like It (2010, Insa Art Space) and The Other Side of the Other Side (2012, Gallery Factory), she began to think deeply about how to bring out the stories of individuals who are obsessed with one thing or another, as well as those who are obscured by events, and in her solo exhibition Ruins (2015, Doosan Gallery) she questioned the attitude of making art through “everyday experts.” Since then, she has shared her questions with collaborators from various fields, including music, dance, criticism, architecture, and literature, and actively sought to expand our senses, holding solo exhibitions such as Kiss Me Quick (2017, SongEun ArtSpace), a contemplation on movement, and Au Magasin de Nouveautés (2020, Atelier Hermès), which explores the contemporary sense of speed through the medium of the eponymous poem by Yi Sang. In the past, she has been awarded the Villa Vassilieff-Pernod Ricard Fellowship, the Hermes Foundation Missulsang, the Gwangju Biennale’s Noon Art Prize, and the SongEun Art Award’s Grand Prize.

Interview

CV

Education

2011

MFA, Graduate School of Communication & Art, Y onsei University, Seoul, Korea

2005

BFA, Sculpture, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea

Selected Solo Exhibitions

2023

Overtone, Barakat Contemporary, Seoul, Korea

2022

Green Screen, Leeum Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

2020

Au Magasin de Nouveautés, Atelier Hermès, Seoul, Korea

2017

Kiss me Quick, SongEun ArtSpace, Seoul, Korea

2015

Ruins, Doosan Gallery, Seoul, Korea

2014

Forget this night when the night is no more, Doosan Gallery, New Y ork, U.S.A

2012

The other side of the other side, Gallery Factory, Seoul, Korea

2010

As you like it, Insa Art Space, Seoul, Korea

Selected Group Exhibitions

2023

Korea Artist Prize, MMCA, Seoul, Korea

Ordinary People, Splendid History, Gyeongnam Art Museum, Changwon, Korea

2022

Watch and Chill 2.0: Streaming Senses, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea, Sharjah Art Museum, Sharjah, UAE, ArkDes, Stockholm, Sweden

Checkpoint. Border Views from Korea, REAL DMZ PROJECT, Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, Wolfsburg, Germany

The Brilliant Days, Ulsan Museum of Art, Ulsan, Korea

Facing the Movement: Crossing/Invading/Stopping, ARKO Art Center, Seoul, Korea

2021

CIRCA, Piccadilly Lights, London, UK

MMCA Performing Arts 2021: Multiverse, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea

Border Crossings-North and South Korean Art from the Sigg Collection, Kunstmuseum Bern, Bern, Swiss

Tactics, Nam June Paik Art Center, Y ongin, Korea

They do not understand each other, Tai Kwun JC Contemporary , HongKong

2020

RhythmScape, Ottawa Art Gallery, Ottawa, Canada

Art Plant Asia 2020, Deoksugung Palace, Seoul, Korea

2019

In one drop of water, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia

Dear Cinema: Difference and Repetition, MMCA Film&Video, Seoul, Korea

2018

Unclosed Bricks: Crevice of Memory, ARKO Art Center, Seoul, Korea

Fictional Frictions, HIAP – Gwangju Biennale Pavilion Project, Gwangju, Korea

re: Sense, Coreana Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

Synchronic Moments, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Gwacheon, Korea

2017

Samramansang from KIM Whanki to YANG Fudong, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea

L’Art au centre, Palais de Tokyo, Paris, France

Tell me the story of all these things. Beginning wherever you wish, tell even us., Villa Vassilieff, Paris, France

2016

Travelling Rennes Metropole Film Festival, Museum of Fine Arts of Rennes, Rennes, France

The Eighth Climate (What does art do?), 11th Gwangju Biennale, Gwangju, Korea

Degenerate Art, Art Space Pool, Seoul, Korea

Who’s Who, Audio Visual Pavilion, Seoul, Korea

2015

This Rose-garland Crown, Atelier Hermès, Seoul, Korea

Ana: Please keep your eyes closed for a moment, Maraya Art Centre, Sharjah, UAE

The 70th Anniversary of Liberation Day : NK Project, Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

2014

Why does the wind blow wherever we remember loved ones?, The Cube Project Space, Taipei, Taiwan

A cabinet of exhibitions, ARKO Art Center, Seoul, Korea

The 4th Anyang Public Art Project: Public Story, Anyang, Korea

2013

The Shadow of the Future, National Museum of Contemporary Art, Bucharest, Romania

What We See, The National Museum of Art, Osaka, Osaka

ArtSpectrum 2012, Leeum Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

Selected Fellowships and Awards

2018

Hermès Foundation Missulsang, Korea

2016

Noon Art Prize, Gwangju Biennale, Korea

Villa Vassilieff Pernod Ricard Fellow, France

2014

Grand Prize Winner, 14th SongEun Art Award, SongEun Art and Cultural Foundation, Korea

Critic 1

The Helping Vowel

Valentine Umansky

I. Of linear and Westernized time

Standing in stark contrast against this congruous landscape, Sojung Jun’s new video, Syncope (2023), foregrounds the toll hegemonic time standards have taken on bodies and souls, proposing a new approach to experiencing reality. By manipulating and collapsing space-time into a non-linear, thirty-minute-long video, the artist brings about more desirable, possible futures. The montage, a blend of footage filmed by the artist in Seoul, Yogyakarta, Paris, and Tokyo, as well as clips generated with the Mobile Terrarium application, follows the mechanical movements of the Trans-Siberian train, as it zips along across continents, compressing the cities’ spaces and times.

Following the curvilinear journey of the train, spanning a length of over 9,289km, Syncope’s premiere at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Korea, is resonant. To Koreans living in a divided country, the longest railway line in the world remains a highly symbolic endeavor. Devised to rapidly connect Moscow to the Pacific port of Vladivostok and expand trade between Russia and East Asia, the train represents a missed opportunity for Korea and Europe to come closer.

Operating an aesthetic, cultural, and conceptual shift, Syncope converts the Transsib into a hypothetical Ginga Tetsudō Surī Nain (Galaxy Express 999) — a steam train running through the stars. Directly referencing the Japanese manga series by Leiji Matsumoto, Sojung Jun’s work embraces spacefaring. The narrative of her video conflates the temporality of a Russian expansion into Manchuria and Korea, which the building of the Transsib underpinned, and the fictional time of Galaxy Express 999, wherein humans have learned how to transfer their minds into mechanical bodies achieving immortality. It reminds viewers how Westernized time constructs and connects nation-state building with space-time and speed management. At the crux of Syncope, the Transsib allows Sojung Jun to pinpoint to the railroad construction fanning flames that later led to the Russo-Japanese War (1904-04), initiating a process which would end, much later on, with the partition of Korea in 1955. The train is also conjured as emblematic of our accelerationist times, its speed and linear path aptly subverted by the artist. But maybe most importantly, the Trans-Siberian impacts the film’s structure. To quote the artist, it acts as “a medium” for the video, be that in the very first scene, in which small lights slowly enter the frame from the bottom left and exit through the top right, or in the very last, which emulates Star Wars unforgettable opening crawl. Within a black sky featuring a scattering of stars, the generic text recedes toward a higher point, as if it was disappearing in the distance; the way trees do, when stared at from the inside of a running train. Throughout, the train’s windows operate as screens, or as a framing device, delimitating our field of vision and conditioning perspective. A temporary wall emulates this idea in the museum’s installation, both revealing and obfuscating Syncope. Suddenly, the horn resounds at a Korean train station. It’s time for the film, and this text, to transition to their second chapters.

II. Bifurcations & labyrinths

In mathematics, the Bifurcation theory is

the study of changes in the topological structure of a given family of curves.

It provides a strategy for investigating the bifurcations that occur within a family.

In common language, though, a bifurcation is a fork in the road;

a break in the line. The train’s derailment…

Reinforcing its structural syncopation, Syncope forks between two main characters, each of them a musician, each of them having experienced their own derailment in life. “Maybe this is the beginning of the second part of my life”, says Celia Huet, as she describes to the filmmaker her move from France to Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

Celia is the character we first encounter, in the starting sequence of the film, but she appears for a mere instant, before a scenic clap, her introduction into the work itself a syncopated entry. Adopted into a French family from South Korea, she had already featured in Sojung Jun’s earlier video, titled Interval. Recess. Pause1 (2017). Her diasporic journey is at the core of Syncope, Indonesia serving as the background for, and at times as the beating heart of, the film. It is in this new home that she started practicing the Gamelan, a traditional ensemble music of the Javanese, Sundanese, and Balinese peoples of Indonesia, made up predominantly of percussive instruments. In one of the crucial scenes of the film, Celia explains having experienced a deja-vu or a deja-entendu (already heard) when she first heard the music during Indonesia’s annual Sekaten. Reflexively looping the work back onto itself, the Gamelan, too, reemerges throughout the shots. The instruments’ sounds percolate to the point at which it is hard to distinguish them from the soundtrack of the work. In interviews, Celia highlights the sensory dimension of memory and sound’s potential to bridge individual and collective experiences. This may explain why, in Syncope, her recollections are often carried over through sound rather than sight. Afterall, isn’t a syncope synonymous to a memory lapse?

The second individual journey we learn from is that of Soon A Park, who also featured in one of Sojung Jun’s Eclipse (2020), and is the focus of the fourth chapter of Syncope. A North Korean gayageum player, Park is from the third-generation of Koreans born in Japan. Her parents moved to the country before Korea was divided, and transited through to what is now North Korea where she studied gayageum before settling in Seoul. As a player of a traditional Korean plucked zither, she crisscrosses the cultures of Pyongyang, North Korea and South Korea in Japan.

Both Soon A Park and Celia Huet make manifest the bifurcations of diasporic journeys, a space of inbetweenness that Sojung Jun favors. Discussing her own relationship to the in-between spaces, the artist explained: “I’m interested in liminal spaces – the things that happen on borders and their ambiguity. (…) I put my passion into re-writing stories, time, and landscapes of individuals who have been left behind by the speed of the city.” Throughout her practice, concepts of translations and transliterations reappear, as in The Ship of Fools (2016), in which she features with three other characters, all taking part in an exercise of live translation. By word of mouth, a sentence is chiseled and transmuted from one language to the next, and the next, and the following. Syncope is haunted by those images of roads intersecting, sometimes symbolically, like in this Indonesian graffiti of a woman with pigtails which is no other than Celia, crossing borders. I am reminded of Vietnamese poet Vi Khi Nao writing about her own family’s exile: “In the exodus mayhem, shrapnel and shards of glass sliced a chaotic cartography of scars on my grandmother’s body, creating bifurcated roads of the war I could use later as map and compass to find my roots.”

The mythological figures of half-demigods Karna and Bari are similar invocations. Both represent nomadic identities hovering between life and death. They act as secret amulets, protecting the wanderers during their diasporic journeys. While Karna is described as the secret son to an unmarried Kunti, who, fearing outrage from society over her premarital pregnancy, abandoned her newly born in a basket over the Ganges, hoping he would find foster parents, Bari guides the souls on their way to the land of the departed. I am reminded of the spirit of Èṣù-Ẹlẹ́gbára, the Trickster God of Crossroads; of Beginnings and Opportunities, who provides second chances… All are liminal deities. But what I liked about Èṣù-Ẹlẹ́gbára is that it is said to have control over the past, present, and future. Often, the spirit is depicted holding a set of keys. As a trickster, it plays time. Bypassing linear constructs, modernist like accelerationist, it derails…

In common language, though, a bifurcation is a fork in the road; a break in the line.

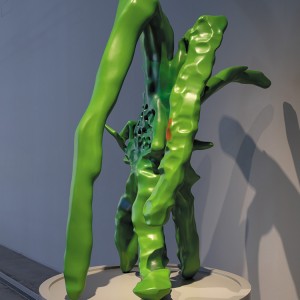

Sojung Jun’s exhibition evokes a labyrinth. It invites visitors to transit through a series of installations before reaching the newest of her works, created for the presentation. One of the first they encounter is Despair to be reborn (2020), a maze-like sculpture of metal, which organizes a video and a set of sculptures in a runway of curvilinear bars reminiscent of department stores. The video refers to an early poem by Yi Sang, born Kim Hae-Gyeong (1910-1937), one of Korea’s most renowned modernist poets, intersecting contemporary and modern Korea. In this text, titled Au Magasin de Nouveautes, the author questioned the concept of the “modern”, problematizing its connection with capitalist economy. Curator Ahn Soyeon2 who first exhibited Sojung Jun’s video highlighted the poem’s enigmatic quality: it combines “a French title” with “Japanese, classical Chinese characters, Chinese and English.” Kim Hae-Gyeong, like Celia Huet in Syncope, inhabit a language I call diasporic —the space of roads that bifurcate.

The installation problematizes some of these diasporic questions. Despite its futuristic look, the maze hints at the design of 19th century Wardian glass houses, oscillating like the video between the future and the past. A product of British imperial pursuits, these terrariums were invented by medical doctor Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward’s to transpose foreign plants into his own geography and time. In 1842, in his essay “On the Growth of Plants in Closely Glazed Cases,” he elaborated on the experiments he started in 1833, explaining how he shipped two glazed cases filled with British ferns all the way to Sydney. One can read that after a voyage of several months, the plants arrived in good condition. Reading about it though, I wondered how many other plants had died as a result of his colonial quest for botanic knowledge… Sojung Jun studied Bagshaw Ward’s cases, and transposed them into the digital world, creating 3D animated sculptures in an application called Mobile Terrarium. These “escaped garden plants,” as she calls them, spread from seeds of the epiphyllum plant, a tropical succulent species that also appears in Syncope. Shown in the video, and accessible to all via the app, the plant-sculptures can be carried into a new setting. Like humans, they may “live here” and still “desire another place”3, like Celia, who in the fifth chapter of Syncope mentions her difficulty to “adjust” to life in France. Epiphyllums are ‘queens of the night’; they bloom only at night and close themselves again before the sun rises. As alien plants, they are “not here to stay”4. Not unlike Youssouf, 4 years old, and Yunus, 2 years old, who sailed from Turkey to Greece, raided by waves, and whose journey is mentioned in Sojung Jun’s work The Ship of Fools, a little further in the exhibition5.

Lastly, in the field of mathematics, the Bifurcation theory is the study of changes in the topological structure of a given family of curves. This came back to my mind as I first sat through Syncope. In the video, each chapter is introduced by a drawn-out curve; each a specific wave pattern. As it reaches its end, almost beyond the generics, all the curves reappear, like a series of bifurcated paths gathered together again…

III. A sudden drop in oxygen supply

In 1993, discussing the theoretical, historical and social framework he called the Black Atlantic, sociologist Paul Gilroy6 explained the effects of “syncopated time” as both counter-culture and constitutive of modernity. The following year, historian James Clifford published his article Diasporas7, which further emphasized the productive possibilities of syncopated time, wherein “effaced stories are recovered” and “different futures imagined.” It is helpful to keep those in mind as one journeys through Syncope.

The title of Sojung Jun’s work hints at a medical context: the short-term cognitive trouble caused by a sudden drop in blood oxygen supply in the brain with, at times, slowing down or interruption of the pulse. While the return to consciousness is most often spontaneous, syncopes bear an intimate relationship to death. They represent the body’s most ultimate loss of control; an interruption in the beat; a disruption in both music and narrative. One of these regular interferences is the artist’s microphone, which reappears in various scenes: at a railway crossing; when the story of Karna is told. It grabs our attention, disrupting our disbelief’s suspension, interrupting a flow, and ultimately reminding us of the filmmaker’s existence.

However, it’s in the editing that the syncopation operates at its best. In various scenes, the screen splits into three vertical windows, the video’s landscape segwaying into fragmented views. While the middle section remains sharp, as if filmed by the phone of a camera, the background image, which appears to the left and right of the central vertical window, lays out enlarged and pixelated sights. It repeats, with a variant, what appears in the center of the frame, making us lose a bit of perspective. Amidst a sea of pixels, Sojung Jun deliberately creates a central path for our eyes to journey on. As author Catherine Clément puts it: “the syncope will always make a fuss: it cannot be discreet, it demands to be seen […] It shows off, exposes itself, smashes, breaks, interrupts the daily course of other people’s lives, people at whom the raptus is aimed.”8

As the film progresses, the rhythmic elements of the video conflict further and further with its tempo and measure, as if the narrator was travelling to the speed of light, à contretemps. It’s at that moment that South Korean musician and DJ, Lee Sowall, takes center stage. Set against a blurry background, she is filmed finger-drumming, but her body and table seem to escape the frame, deriving beyond gravity. The image against which she stands turns into a decelerated image of central Seoul, pictured from a train, but slowed down to the point of staggering. And suddenly the train derails. A leap out of the space-time continuum. “In the end, we all move at different speeds,” says Sowall. “We live in the gaps.”

I remember asking myself what lived in the intervals when I first saw Himali Singh Soin’s video The Particle and the Wave (2015), in which the artist studies the rhythmical pattern of Virginia Woolf’s The Waves. Working through the author’s novel, Singh Soin erased the words to only leave the semicolons behind as hinges to help us measure time. What lives between the beats, the words, the times? Are there plants, mycelium, that spreads and grows surreptitiously like Sojung Jun’s epiphyllum? What lives in the off-key sounds of the Gamelan?

In one of my last emails to Sojung Jun, I asked her to tell me more about the concept of Nonghyun, central to the gayageum’s left-hand technique mastered by character Soon A Park. She responded: “nonghyun is an unwritten sound,” “a void,” “the margins of sound that goes outside the notation.” Funnily, in one of my obsessive digs about the work and Lee Sowall, I read an interview in which the journalist inquired about the precision of her beats. Asked how she managed to remain so precisely on beat without an obvious click track, Sowall too praised the interstice: “I’m obsessed with tempo, which can work for you or against you. It comes naturally to me to lock in to the beat. But when I’m finger drumming, I try to forget what I cared about when I played the drums.” “I’m a little bit more free.” “Finger drumming has been a getaway to escape.” How does one operate from a counter beat perspective, that very “counter beat” which Paul Gilroy called upon in his book, Black Atlantic. The Gamelan, whose actual name comes from the Javanese word gamel, which refers to the act of striking with a mallet, in other words the beat. But what makes it unusual, and connected to the gayageum, is that it relies on an ensemble working on scales that are not standardized. Within one set, each instrument is deliberately tuned off so that resonance occurs only when all are struck simultaneously. Dissonant to the point of harmony…

In the text accompanying her eponymous show9, art historian Daria Khan wrote: “a syncope is a multi-format ‘tender interval’ which can be described in music as an unstressed ‘empty’ beat; in linguistics as the suspension of a syllable, or a letter; in medicine as a partial or complete loss of consciousness. In this exhibition, syncope acts as a metaphor for rapture, delay, lacunae, and displacement.” As she would, I ask: can the syncope create an additional, unstressed beat, in the interstice, for a different time-space continuum? Phonologists and linguists came up with a concept for this idea: they call it the helping vowel. It refers to a rule of pronunciation that inserts a “brief” vowel as a vocalic release to help us pronounce a word with more ease. A surplus sound, if you will. The very last scene of Syncope occupies the very space of that interval. After the train has reached the speed of light. At its climax, the video takes on a most experimental quality, suggestive of avant-garde cinema, with its showing of sprocket holes, splice marks, and flickering. As Sowall finishes her set, afterimages of her body appear in a staccato of slow-mo, like a comet’s tail lingering in the sky, glitching.

Right as I reached the last line of this text, I received a mysterious PDF document titled “Clues.” In it, Sojung Jun revealed: “nonghyun is the most characteristic and important technique in Gayageum. It produces various decorative sounds in addition to the original note. As it is not notated; it is both objective and subjective; resolute, like a big wave.”

References

Clément, Catherine. Syncope, The philosophy of Rapture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1994. 328.

Clifford, James. Routes: Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth Century. Cambridge, Mass. And London:

Harvard University Press, 1997.

Gilroy, Paul. The Black Atlantic. Modernity and Double Consciousness. Verso London, 1993.

Powell, Amy L.. Time after Modernism: Postcoloniality and Relational Time-Based Practices in Contemporary Art. Wisconsin: University of Madison Wisconsin: 2012. 276.

Jun, Sojung. “Clues.” accessed over emails on 29 October 2023.

1 Interval. Recess. Pause. 2017, is exhibited at the entrance of Gallery 2 at Korea Artist Prize, where Sojung Jun’s artworks are installed.

2 Ahn Soyeon, “Standing before dazzling novelty,” 2020, accessed October 29, 2023, https://junsojung-text.tumblr.com/,

3 James Clifford, “Diasporas,” Cultural Anthropology, vol. 9, no. 3 (1994): 255.

4 Ibid.

5 Sojung Jun, The Ship of Fools (2016).

6 Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic. Modernity and Double Consciousness (Verso London, 1993).

7 Refer to footnote 3, 264.

8 Catherine Clément, Syncope, The philosophy of Rapture (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1994), 251.

9 Syncope, a group exhibition featuring Chooc Ly Tan, Himali Singh Soin, Lala Rukh, Mira Calix, Ruth Beraha and Qian Qian, curated in 2021 at Mimosa House by Daria Khan.

Critic 2

Ayami, Umbra Garten

Bae Suah

Houses. A few low houses quietly crouching in a field apart from one another. Clouds and willow trees. Winter. Hills, rivers, and bridges. Silent girls. Landscapes that are not here-and-now. It is an image that a friend is said to have made. The friend informed me of it in a letter. I had not known that this friend made paintings. It is because he said he was a tour guide and ran a used bookstore. I’m not sure if I can even call him a friend. We have never met. We haven’t even seen a photo of each other, and have only exchanged letters. I received my first letter before I graduated from college, so our letter exchange has continued on for quite some time. Of course, there were several periods in between, when years passed, without either of us hearing anything from the other. It may be a coincidence, but certain times in my life that could be called events always occurred during those gaps in letters. (Marriage, employment, vacation, travel, divorce and unemployment, small successes and big failures, bankruptcy, illness, childbirth and funerals, things requiring documents, things that make up the visible contents of life, involving joy and despair) I imagine that it was probably the same for my friend. As if a dream were suspended for a moment, and rote reality began to set in. When such a period came to an end, and we suddenly thought of each other and began to write letters again, we were all of a sudden in the “shaded garden.” (Breaking the silence of the past several years, we were back in Umbra Garten) In this text, I will call that friend by a random name. That name is Aksum. Coincidentally, Aksum is also the name of a city in Ethiopia, but I have no special connection to it. I have never been to Ethiopia, and, obviously, I don’t know an Aksum. One day, there was a proposal from Aksum. He wanted to make a painting of me. Not my portrait, but a painting attributable to me, uttered by me, from me. For this, I must become a unique word, a name. Or, I must become its sound. He said he wants to hear that sound. Perhaps a sound that consists of something flowing between one word and the next. In order to make the painting, Aksum needs a bit of my help. Though it may be a little, it is an inner help that transcends all physical boundaries. Does that mean he needs a description of myself or a text that describes me? No, that’s not it. Clearly, he said he didn’t need a photo of me. “What I need is your imagination itself,” wrote Aksum. “Imagine you are looking at your painting at this moment,” Aksum wrote to me. “Imagine, one day while you are traveling, you happen to go into an art museum, and there, you unexpectedly encounter a painting. The title of the painting is the same as your name. That painting is you. You check the name of the artist. It is Aksum. So the painting you are looking at before the fact, is like the painting of you I have yet to make. Please write to me what you will hear from the painting, the words that will ring in your ears, the echoes of those words and echoes of those echoes. I will make your painting based on your writing. The painting that you will one day come across unexpectedly and that will arouse something in you. In order to paint that picture, I need your writing that the painting will evoke beforehand. I need an imagination that anticipates your imagination. In this way, we, or rather the painting, leave everything open-ended and enter the cosmic ouroboros.” This is part of a novel. This will all be part of a story in a novel. Like the way we all become part of a story that already exists, from the moment we utter our first word. To live means to automatically become part of a story. As I was writing this novel, I thought I was writing a story that I would bring into being, yet at the same time, one by which I would have already been made from it in the past. That I write means someone’s voice is writing me. It means, I have heard the voice of the whisperer in advance and I am shadowing it. “Tell me what you will hear,” wrote Aksum. That became my writing. Writing, what was the inception of writing, I wonder. Where does writing begin? Love has no beginning or end, in my view. It may also be the case for a single book. Those things to which we have decided to entrust our lives. All of a sudden, I am in the middle of a large station square overflowing with crowds. “Ayami, let’s take the train now,” my traveling companion says. And so I know my name is Ayami. When I ask where she wants to go, my companion says without hesitation that she wants to go to the Yalu River. She doesn’t know the river, but she heard that it was a river that flows along the border between China and Korea. She, who was a writer of detective novels, said she was planning a story about a woman who will die on a train crossing the Yalu River train bridge, and for that reason, she felt she needed to go to the Yalu River herself. So she came to South Korea, a country that was unfamiliar to her. She said places are magical. She said old places that harbor stories draw her to them. But you can’t go by plane, because flying is supernaturally an act of losing your feet. Feet have the power of returning. Once you lose your feet, you can never return to the river again. My companion spoke again. She just had an idea, however, that she wants to name the woman who died on the Yalu River train bridge “Ayami.” She said that as soon as she heard my name, she had a flash of inspiration that the name suits her main character. Of course, as a matter of courtesy, she would need my permission for this. Although, even if I didn’t want to, I know very well that there is no reason why she shouldn’t give my name to her protagonist. Although a name is unique, it certainly doesn’t make it an Iexclusive property. Also, Ayami is a name I gave to myself, because I found it by chance in a book somewhere. In the book, Ayami was the name of a spirit. It was written that the spirit dwells in the shaman’s dreams, marries him, and stays with him for the rest of his life. Also, Ayami is a whisperer. The shaman conveys Ayami’s whispers to people. I know absolutely nothing about the detective novel my companion is writing. Her detective novel, in which Ayami will appear, isn’t finished yet, and she is just sketching out a draft. However, if a heroine named Ayami were to die, how different would that be from my own death? I instinctively want to prevent Ayami’s death, if possible.

I say to my companion from Germany in a light tone, “We can’t go to the Yalu River, because we can’t reach the the Chinese border where the Yalu River is located by train. This country that you are in is like an island.” My companion is greatly disappointed. And she makes the excuse that she didn’t know because it was her first time crossing into the eastern part of the Caucuses. Occasionally, a sentence lingers in my head. It is a sentence made of images. I move through the fragmented lexicon. What I am looking for is neither language nor writing, but a voice. I try to translate the whispering voice, leaving aside grammar and the many sensations that come at me all at once, into the form of writing, but I have never once succeeded. There is a vertigo induced by the boundless gap between the voice that spoke before me and the letters that dictated it. But sometimes that vertigo confers freedom to the act of writing. It is because writing is not a race towards a goal. I am interested in limitless, unconstrained writing that takes place in a closed environment under restrictive conditions. For example, the carriage of a night train crossing the Yalu River railway bridge. For example, the island if an individual’s life, for example, the entire life that takes place within the crystal ball of the medium. “So, what kind of writing do you do specifically?” My companion asks again. I reply that I am writing a detective novel. But the landscape of all of these words is not really here. This conversation never actually occurred. The meeting between me and my companion, the Yalu River, and the train are events that have never happened even once. The world was like a dream dreamt up simultaneously by inseparable eyes. I have the dual constitution of writing and voice.

The medium whispers: You don’t know this, but my name is Mill. I write it as M. The name came from my mother. My mother’s childhood name was Mill, like mine. I was also called Mill in my childhood. But the only person who called me Mill was my mother. Because no one other than my mother called me at all. In school and work, government offices and documents, marriage and divorce, birth and death, I exist under a different name. A name on paper is the name that officially declares anonymity. After leaving my mother, I forgot my name, but one morning, after receiving a letter, I became the most Mill. This is part of a novel. Mill has a thin, transparent boundary. Mill flows and permeates. At the beginning of the story I received a letter, and both the sender and recipient’s names were Mill. It was a letter that gave me a name. I can’t even imagine what times and spaces the letter passed through to finally reach me. But one thing is certain, the letter was written in the year I was born, and for some reason, it wandered from one address to another before it reached me. I woke up this morning, for certain, in Berlin. However Mill, my love Mill, is writing this having never left the hometown where she was born. Mill’s longing for a distant place is uncontaminated. It still has a transcendental character. If so, then, am I, on the contrary, full of loss?

I reveal to my companion that I am in fact a tree. “Therefore I cannot cross the border. To be honest, I have never once crossed the border.” “But didn’t we first meet on a train to Berlin?” My companion responds in confusion. “At that time you had your laptop screen spread out on the folding table attached to the back of the seat in front of you, and you were writing in a foreign language that I couldn’t read.” Still, I maintain my claim that I am actually a tree. I have an artist friend whose exhibition was held in a cabin in the mountains. Those invited went up the mountain path carrying heavy backpacks filled with stones. I had to carry several stones on my back. Anyway, at this exhibition, I saw the scene of two trees kissing. The tree hanging from the high ceiling of the cabin, which was originally a granary, swayed gently in certain directions depending on the slightest current of air, changes in humidity and temperature, and the presence or absence of wind, and for brief moments when the climate and physical laws fortuitously allowed, it narrowly grazed the branches of another tree that had fallen to the ground. During the ten days of the exhibition, we slept in the front yard of the cabin in sleeping bags and ate our meals from the dry bread and biscuits we had each prepared and fruit from the apple tree by the river. It was late summer, nearly fall. When we woke up in the morning, the first thing we did was to gather mushrooms and the apples that had fallen overnight. On hot sunny days, we swam in the river. When the Sun went down, all the doors and windows of the cabin were opened and the lights in the exhibition hall turned on. The tree begins to sparkle. We put the stewed apples we made in the kitchen on the bread and ate it with potatoes sprinkled with warm milk for dinner. Apples were plentiful and milk and potatoes could be obtained from neighboring farms. At night, we went into our sleeping bags with stones heated from the campfire. “Is there really no way for a revolution, or an art to survive in a way that is distanced from power, in a way that is furthest from the center?” wrote Aksum in the letter. The question fascinated me. This is because he chose “survive” instead of the word “succeed.” On the last night of the exhibition, we piled up the stones we had brought with us in the yard, and my friend placed the two desiccated trees from the exhibition hall on top and lit them on fire. The tree burned for a long time. We turned into ash. Ashes suggest that something that has now lost its form had been there. Ashes as a way for objects and landscapes that are not here to exist. On the night train back to Berlin, I wanted to record my impressions of the exhibition in a short sketch. (In a way that is distanced from power, in a way that is furtherest from the center) At times, an infinite wave of emotions that I am unable to face overwhelms me.

Ayami once worked as a telephone partner under the pseudonym Yoni. One reason was that the income earned as an office worker at the audio theater was terrible. (“A telephone partner, what exactly does that entail? Is it a euphemism for a typical phone sex service?” My companion asks, interjecting) Plus, the theater is scheduled to close soon, so Ayami will become unemployed. Ayami borrowed the name Yoni from her German teacher who went missing. For several years, Ayami went to Yoni’s house every day for German lessons. Yoni took out her German books, notes, and letters piled up inside a worn out trunk and read them to Ayami. That was their lesson. But one day, Yoni suddenly disappeared without letting anyone know, and never appeared again. Only her name remained. A name that has lost its body is like ash. Ash is a word made up of dust and suggestion. After that day, I went looking for Yoni. My companion is intrigued by Yoni. The fact that Yoni (or was that Ayami?) had two different kinds of jobs as a German teacher and a telephone partner simultaneously, also intrigues her. It is a setting suitable for a detective novel. What on earth kind of woman was Yoni? My companion asks every time she thinks of it. I answer that Yoni is like a garden submerged in a slight shadow. The kind of garden that appears every night in your dreams. I say her severely pockmarked face from a fever she suffered as a child, and the long period of solitude that she had become accustomed to was likely not unrelated. My companion says she wants to make Yoni into Ayami’s doppelgänger. In her detective novel, that is. Perhaps Ayami will die with the name Yoni. Or, you may already be dead under the name Ayami. Or even after death, will she continue to go on living under the name Ayami? Am I Ayami, who was called Yoni? Or, the opposite? At times, an infinite wave of emotions that I am unable to face overwhelms me. I think of the person who gave me my name. She sent me a letter one day. I open the envelope. The moment I pick up the letter, the paper that is old as a lifetime turns to ash. I am ablaze.

I first learned in Altai that a name is a gift. I was standing in the middle of the grassland. All around were endless green hills, flocks of sheep, a cold blue lake in a crater, and stones like bones rolling around the earth. The reason I went to Altai was to see the tombs of the Scythians. The Scythian tomb pointed out by the guide was a spacious and low round mound shaped like a large pit covered with earth. There were no signs or information panels in the middle of the grassland. Perhaps I had a vague hope of discovering a place, a symbol, or a name that I may have come from. Far away, a herd of horses galloped away. Shepherds chased the herd of horses. In front of the Scythian tomb, someone said he wanted to give me a newborn foal. He said it was a foal that had not yet been named. I answered that I was grateful but could not accept the gift. I cannot take the foal home, it’s impossible. “But you don’t have to take the foal home. You can’t and it isn’t possible. The foal must, of course, stay near its mother and with its own species.” The guide explained. “That we will give you a foal as a gift means we will give it your name.” In the meantime, the shepherds who were chasing the herd of horses caught the foal using a rope and had brought it in front of me. I did as the guide told me and called the foal by my name, which would now belong to it. People took turns taking a sip of the horse wine from the golden bowl and sprinkled the rest in the air. That was God’s doing. It was exactly the way my grandmother did it. (Sprinkle a spoonful of rice and meat in the air) The gift has been delivered. The people untied the rope, and the foal frantically ran away towards the herd of horses. My name remains here in the land of Scythia. By its mother’s side, together with its own species.

On the night I set out to find Yoni, my companion accompanies me. Because I promised that if she did that, I would lend my name, Ayami, to her heroine. Every time we come across a public phone booth, we call Yoni. But, it is always the voice Yoni recorded for her telephone partner on the answering machine that answers every time. My companion asks me to translate it. So, imitating Yoni’s voice, I whisper into my companion’s ears. “I see you want to speak to Yoni. Yoni does too.” This is what that voice whispered every time, I tell him. “I have a story for you. Let me tell you that first. Listen…” While I continued to whisper, my companion looked a bit puzzled. “This seems a little unusual for what we would normally imagine from a telephone partner service….It is clear that Yoni’s business did not make a large profit.” I don’t know if it explains it, but I say Yoni was poor, just like Ayami. Yoni’s telephone partner service only had a few customers, and above all, Ayami was her only German student, so it would have been difficult to even pay the rent. My companion nodded her head as if she understood. We decide to take the train. Although we cannot go to the Yalu River, Yoni wanted to go as far as possible as the train would take her (this was my companion’s claim). Imagine, she says. Imagine, when you finally want to run away, when you desperately want another here-and-now that is furthest from this here-and-now, when you want it without anyone knowing, which train, heading towards which direction, would you get on. For instance.

Uru. That is my answer. Uru is a type of name. The name rose up suddenly one day in my head like the first Sun. Only after a while did I realize that the name came from one of the first cities of humankind. Uru wakes up in a small inn in northern Brazil, realizing that all of her memories have disappeared. Actually, it’s not strange that Uru has no memories. It is because all first things have no accumulated memory. The spirit wants to enter the body of this Uru. The spirit needs a body. It is because it lost the body it originally resided in. The spirit, having lost its body, its home, wandered around for a long time. It was a long journey to find Uru. The spirit is a whisperer. The spirit’s newly inhabited body accepts the memory of the spirit as its own. So Uru begins her story. The story is the blaze of a bush that burns on its own. No, is it music? No, is it poetry? “Imagine.” My companion says. “Imagine, Yoni left without anyone knowing. Since you were Yoni’s only student and only friend, it is possible she left you a letter. Yoni put the letter in the mailbox at central station, but for some reason, it hasn’t yet reached you. Imagine, Yoni, who left on a trip, suddenly falls off the train one day and loses all her memories. So, Yoni forgot her name, forgot you, and the moment she arrived at some unknown place, she came to believe that she was Uru.”

This is part of a novel. When it began, the mail person came and I was handed a letter. The letter contains the events of the day when I was born. At times, an infinite wave of emotions that I am unable to face overwhelms me. At times like this, I fall into the illusion that I am safekeeping the events of that day intact in my memory. The events of the day when I was still nothing but a little salt and water, a whisper, and other soft substances wrapped in a semi-translucent membrane. That day, in this desolate world without a single blade of grass, your name is Umbra Garten (Whispers: I am like a slightly shaded garden, the kind that appears every night in your dreams) Who is it that whispers in my ear the words I am writing now, perhaps it is why I had no choice but to write this letter. A letter that will reach the shores of your lost body after countless years have passed, for Mill, my love.