Oh Min

Oh Min is an artist who explores the nature of time through experiments in various mediums such as music, sound, and performance. Oh expands the realm of the senses in her research of time. She studies the temporality, movement, and characteristics of light in performance and visual arts, delving into physical considerations affecting gaps in time and paradoxical contradictions that range from the perfect to the imperfect. She has held solo exhibitions at Platform-L Contemporary Art Center (2020) and Atelier Hermès (2018), and her works are housed in the Seoul Museum of Art, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art and SongEun Foundation.

Interview

CV

Education

2008

MFA, Graphic Design, Yale School of Art, New Haven, USA

2000

BFA, Industrial and Visual Communication Design, Design, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea

1998

BM, Piano (major), Instrumental Music, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea

Selected Solo Exhibitions

2020

Min Oh: Invitee, Attendee, Absentee, Platform-L Contemporary Art Center, Seoul, Korea

2018

Étude, Atelier Hermès, Seoul, Korea

2017

Notations, DOOSAN Gallery New York, New York, USA

2016

1 2 3 4, DOOSAN Gallery, Seoul, Korea

2015

MIN OH: TRIO, D project space, Seoul, Korea

2012

The Suite, De Nederlandsche Bank Gallery, Amsterdam, Nederland

2011

Min Oh: How Things Genuinely Speak and Sing, Kunsthalle Erfurt, Erfurt, Germany; Onomatopee, Eindhoven, Nederland

Selected Group Exhibitions

2021

(upcoming) Thomas (co-curated by Min Oh, Suzy Park), Total Museum, Seoul, Korea

Watch & Chill, watchandchill.Korea; MMCA, Seoul; M+, Hong Kong; MAIIAM, Thailand; MCAD, Philippines

New Ways of Living for ▭, Suwon I-Park Museum of Art, Suwon, Korea

2020

Liebesding – Object Love, Museum Morsbroich, Leverkusen, DE

2019

Take ( ) at face value (curated by Kim Kim Gallery), Korean Cultural Centre Australia Gallery, Sydney, AU

Poetic Diction, Pohang Museum of Steel Art, Pohang, Korea

2018

Nuit Blanche, Cité internationale des arts, Paris, FR

2018 Title Match: Hyungkoo Lee vs Min Oh, Buk-Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

Object Love, Museum de Domijnen Hedendaagse Kunst, Sittard, NL

Collecting Highlights: Synchronic Moments, MMCA, Gwacheon, Korea

2017

2017 SongEun Art Award Exhibition, SongEun Art Space, Seoul, Korea

Ex-exhibition (curated by Haejin Pahng), Platform-L Contemporary Art Center, Seoul, Korea

Moving / Image (curated by Haeju Kim), Arko Art Center, Seoul, Korea

(screening) Le monde Plié: séminaire in(ter)disciplinaire & projection, La Générale, Paris, FR

Score: Music for everyone, Daegu Art Museum, Daegu, Korea

2016

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland – Virtual Reality, Suwon I-Park Museum of Art, Suwon, Korea

wellknown unknown (curated by Sungwon Kim), Kukje Gallery, Seoul, Korea

(screening) La Nuit de l’Instant, Marseille Expos, Marseille, FR

Emerging Other, Arko Art Center, Seoul, Korea

2015

Move & Scale, Audio Visual Pavilion, Seoul, Korea

Random Access 2015, Nam June Paik Art Center, Yongin, Korea

2014

Korean Young Artists 2014, MMCA, Gwacheon, Korea

2013

(screening) Modern Times: Modern Housekeeping, Eye film museum, Amsterdam, NL;

Cinema Zuid, Antwerpen, BE”

2012

Rijksakademie Open Studio, Amsterdam, NL

KAAP, Fort Ruigenhoek, Groenekan, NL

2011

Rijksakademie Open Studio, Amsterdam, NL

Selected Awards and Fellowship

2021

Seoul Foundation for Arts and Culture, Seoul, Korea

2020

SongEun Foundation, Seoul, Korea

2020

Seoul Foundation for Arts and Culture, Seoul, Korea

2019

Arts Council Korea, Korea

2019

Seoul Foundation for Arts and Culture, Seoul, Korea

2018

Arts Council Korea, Korea

2018

Seoul Foundation for Arts and Culture, Seoul, Korea

2017

Fondation d’entreprise Hermès Art prize, Paris, FR & Seoul, Korea

2017

SongEun Art Award, 4 Shortlists, Seoul, Korea

2014

Dommering Foundation, Amsterdam, NL

Selected Residencies

2018

Fondation d’entreprise Hermès, Paris, France

2017

DOOSAN Residency New York, New York, USA

2014-2015

Artists residency, The Cité internationale des arts, Paris, France

2014

Regular Residency Program, Seoul Art Space Geumcheon, Seoul, Korea

2011-2012

Rijksakademie, Amsterdam, Nederland

Selected Collections

National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea

Daejeon Museum of Art

DOOSAN Gallery

Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art

Seoul Museum of Art

Songeun Culture Foundation

Platform-L Contemporary Art Center

De Nederlandsche Bank, Amsterdam, Nederland

Rijksakademie, Amsterdam, Nederland

Critic 1

A sensory experimentation that deconstructs the temporality of modernity

Jade Keunhye Lim (Director, ARKO Art Center)

Many aspects make Oh Min’s work fascinating: the artist’s experimentation in deconstructing, crossing, or expanding upon existing mediums and genres in defiance of limitation; the ways in which she forges relationships and attitudes among artists in different fields, collaborators, and spectators; and the novel sensation she awakens in subverting the standardized temporality that the modern system has tamed it to be.

The audience familiar with the language of visual art may find the texts discussing the artist’s works somewhat foreign, especially for their prevalent usage of terminology and concepts pertaining to music. However, understanding Oh Min as “an artist addressing the sense of anxiety by means of the universal structure of music” and the methods or materials to “control” situations and objects as central to her work rather than its musical elements allows these texts to feel more accessible. The artist has stated her early works to contain “antipathy and ridicule toward external forces that invade an inherently personal space of control” and subsequent works to “contemplate all methods of control, including rules, systems, rituals, and hierarchies.” Accordingly, her video works, which may be characterized as “music sans sound,” simultaneously evoke nuanced tensions and aesthetic pleasures through a method of musical construction the artist deemed most efficient in controlling the performer’s movement and visualizing it into hyper-restrained, sculptural beauty.

Paradoxically, it is precisely from the moment the interference of chance sways the complete control compulsively pursued by the artist that her work becomes even more intriguing. Up until 2010, Oh Min’s entire modus operandi of filming, recording, enacting the performance, narrating the voice-over, composing, and performing the music was done alone. To “conceptualize” time and “compose it as material” for her practice-oriented experimentation, however, she needed a hand from experts working in genres other than time-based art. “Collaboration with others that require appropriate distance and balance while gaining new knowledge and skills” ultimately boils down to “questions about the desire and value of the artist.” In other words, unlike a faultless performance that follows unilateral instructions, collaboration demands finding common ground by “relinquishing complete control to obtain new inspiration or discover the joy of broadening one’s technical scope.” The sense of a temporary community developed by the artist, collaborator, and audience that withstands clashes and conflicts by enduring disparities and differences seems to have brought both a deepening mellowness and steadfastness to Oh’s work.

In her recent pursuit of “research and experimentation on the properties of time,” the artist “explores how the body senses, manages, consumes, and generates time” as she studies the structure and correlation between the presence of a performance and its video recording, which accumulates sound and images in crystallized time. This leads to the artist’s tangible realization of the concept of time, generation of a sense of time through sound and images, or various questions around the material and form of temporal art. Though the artist’s concern may seem rather abstract, it can be inferred that this eventually touches the utterly practical dimension of life that is the (re)establishment of the relationship between oneself and the world and the (re)construction of quotidian sensibility. Due to the restrictions to our time and space brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic, we realize that the sense of time and space familiar to us is, in fact, simply the outcome of having been accustomed to a certain social system for a long time.

From Oh Min’s practice-oriented work seeking new connections between heterogeneous elements, embracing both the tension of control and the flexibility of collaboration, and cultivating a new consciousness and sensibility that transcend existing frameworks and norms, her efforts to preserve the individual’s subjectivity within a massive social system are heartfelt. By listening to her inner voice rather than jumping on the bandwagon or repeating existing discourse, she creates a unique methodology, the promise of which is the reason I am recommending Oh Min for the 2021 Korea Artist Prize, especially now that it has become self-evident that returning to a pre-COVID-19 world is impossible.

References

Ki, Hey-kyung, Hae-jin Pahng, So-yeon Ahn and Il-u Ju. 2018 Title Match: Lee Hyung-koo vs. Oh Min. Seoul: Seoul Museum of Art, 2018.

Pahng, Hae-jin. “A/B: Oh Min and Pahng Hae-jin in Conversation.” Okulo, vol. 3, 2016.

Oh, Min. Invitee, Attendee, Absentee. Seoul: Workroom Specter, 2020.

Oh, Min. Score by Score. Seoul: Workroom Specter, 2017.

Lee, Jeong-seon. “Oh Min, Experimenting With Musical Construction.” Hello! Artist, 20 December 2016, accessed 1 October 2021, https://terms.naver.com/entry.naver?docId=3580967&cid=59154&categoryId=59154.

Critic 2

The Precariously Urgent Here and Now

Park Suzy (independent curator)

Introduction

Regardless of the times, the most urgent and the most important rarely refer to the same. On the one hand, urgency is clearly proven through the voice of the majority driven by its many requests or rallies. Sometimes, importance comes from being obvious or urgent. On the other hand, what is important does not always seem urgent. If we may deem “classics” those works that the public has revered since their birth and celebrated time and time again, then it could be said that there must exist something that has always been held important in art. In other words, what is important remains important even after hundreds of years, standing separate from the specificity and preference of the subject, who assigns and calls for this importance. If there is one important value that has stood the test of time in the history of art, it must be newness. Newness has been experimented with, exploited, challenged, and considered cliché, only to be resuscitated and endlessly discussed thereafter. Newness in art has not been a value strategically required for social transformation, cultural discovery, or overthrowing tradition, as there is innate motility sufficient to instigate newness itself. Therefore, newness can be considered a classical value of some sort.

Then what can be said about the proposition that there is no more newness? Is it a manifestation of arrogance, a kind of renunciation, or merely pedantic rhetoric? Given that art is not created for the sole purpose of serving newness, the arguments run extreme on either side and may have been exaggerated. Nevertheless, judgment on what is new is inevitably fraught with immense limitations based solely on the experience and knowledge of those who make the judgment. This signals suspicion that “I,” the sensory receptor perceiving and interpreting these senses, may have become outdated myself while accumulating various experiences over the years. Furthermore, “I” can stay alive for a mere one hundred years. Even if “I” tried, no way could “I” obtain full knowledge of the past 2,000 years. This renders “me” insufficient to judge whether an artwork will become a classic in the future. In such a sense, artists might be those who must strive to be both the most trusting, especially when it comes to the senses, and the most excluding of themselves.

Oh Min is one of those rare artists who continually strive to expand their scope of knowledge while not hesitating to question what they supposedly know. Her expansion of knowledge does not necessarily pertain to the time that has yet to come, nor to the time that has already passed. Such tendencies make the system of knowledge she is constructing all the more distinctive. In a way, it seems as if she has a sense of mission, although, interestingly enough, one without a goal. More precisely speaking, the lack of any goal makes her sense of mission all the more interesting. The goal here refers to something beyond reaching fulfillment and being fulfilled by a certain action. It refers to employing action as means to earn something, a result entirely separate from the pure joy that arises from the action itself. For any human in

action, and for an artist in particular, technē and methodos, as well as action and choice,1 carry enough meaning as is. That is why we are curious about the motivation and process behind her actions, what she seeks, and what she tries to avoid. This writing follows artist Oh Min’s perspective on art, her attitude and point of view, and her practice and program. The writing also attempts to answer the question “Would it be possible to discuss all of Oh Min’s works without listing the inherent uniqueness in each and every one?”

Technē and Methodos, Action and Choice

“So if what is done has some end that we want for its own sake (prakton),

and everything else we want is for the sake of this end;

and if we do not choose everything for the sake of something else,

then clearly this will be the good, indeed the chief good (ariston).

Surely, then, knowledge of the good must be very important for our lives?”

― Aristotle, Book I, Chapter 2, Politics as Master Science of the Good, Nicomachean Ethics2

Oh Min has always said that musical performance is her mother tongue. It is difficult to tell how proficient she is in her mother tongue, or whether she still has affection for it, from such a statement alone. However, as inherent in the origin of the mother tongue, it is possible to surmise that the artist would have spent a long time in such a language. That would have been a process of refining her body and thinking with the perspective and attitude of a performer. So what is this perspective of a performer? How does it differ from the attitude of a painter or the perspective of a sculptor? It is alike in that all three involve practice. Nevertheless, the resulting sound makes the performer’s practice distinctive. Heavily impacted by the “passing of time,” sound is made only to disappear, which is as natural as the providence of the universe. However, this disappearance of sound — or, in other words, the direct confrontation of the passing of physical time, inability to fabricate indestructibility or leave behind visible material, and the world of musical performance that cannot pose as infinite — seems to have left Oh Min with a notable question: what is really happening while time passes?

Oh Min has been asking whether art has accepted time as its material. Given that history and time are inseparable topics in art, what made such a question possible? Oh Min seems to refer to time in art as the “notional idea of time,” such as implied time, time accumulated as depth, time not exposed, nonlinear time, stopped time, and time not heard. Such a notion of time has indeed served as an essential factor that has given birth to exciting works. However, it seems Oh Min could not overlook the cruelest aspect of time, the changes it creates as each minute and second pass by. Then what is “time as a material” to Oh Min? First, we must look into her definition of art materials. Historically, art materials have expanded from those traditional and physical to the intangible, such as light, sound, or movement. Oh Min further adds, “Representation in art incorporates events, history, and culture as its materials, which indicates that content matter or themes can also be considered as material.” She continues by saying, “Forms, questions, and reason are also in the realm of material,” stating with certainty that “understanding the properties of a material as well as an artist’s attitude towards it is part of material research.” If so, what are Oh Min’s thoughts on the form of art? She says, “Form can be understood as physical, conceptual, and historical relationships established among expanded materials, as well as the organizational structure resulting from such relationships.” She also adds, “Form offers a chance to glimpse into the method of reflection, as a tool and result of said reflection.”

In other words, for Oh Min, art materials are not limited to matter based on visibility. Her materials are both complex and pure in nature. Including gestures of the practitioner, thoughts of others, and audience experiences, she takes on materials that are in realms impossible to control or fully comprehend. Such an approach fundamentally differs from the conventional, which had simply accepted the result of an uncontrollable event as a work of art. Moreover, to Oh, form goes beyond a frame that holds its content. Not the work’s outer appearance or its concocted method of communication, the content itself becomes equal to its form, as the work’s essential and true nature. Then the artist’s technē and methodos, actions and choice, can finally address art’s material, form, composition, and relationships. Such a conversation begins with the artist’s self-definition, although, of course, such a definition never reaches completion. This impossibility may be said to be the drive that generates art or the immaculate pursuit of art.

Sufficient Conditions for a Radical Relationship

“The dividing line between authentic art

that takes on itself the crisis of meaning

and a resigned art consisting literally and figuratively of protocol sentences can be found in the following.”

— Theodor W. Adorno, Aesthetic Theory3

The most radical politics does not have an objective. This directly equates to the artist’s attitude regarding her reflections on the relationship between materials. Oh Min frequently questions the “equivalency between sensory materials” and the “state when nothing serves as a background for another.” The “equivalency” here must be examined. Equivalency is not a movement that negates the hierarchy of social status. Treating variable materials as equal, alike, or impartial is identical to not making any difference; it is a declaration of refusing to make anything. Ultimately, relationships between the sensory materials are independent, considering the validity of unique properties that create their unique differences. It is only mutual recognition and deep understanding of each other that sustains this independence. Therefore, “equivalency” becomes a sufficient condition for the pure pursuit of a holistic sensory state. In other words, the truly greatest of politics, in which actions without any purpose densely overlap with one another, is the state of “equivalency.”

In such a set-up of radical relationships, then, what conditions should be considered? Oh Min seems to begin her questions with those dependent or essential relationships that have been considered as given. A question such as “Is sound essential to music?” makes one wonder what conditions are necessary for something to constitute music. Such a method of inquiry leads to many relevant questions: Is image essential to art? Is structure essential to reflection? The way of asking such questions puts a brake on almost everything we had deemed “natural.” It raises questions about common sense and conventional wisdom that construct our experiences, a process that is in itself a radical model of art. However, Oh does not stop at this radical gesture.

Satisfying an expanded notion of material and a radical conception of form by themselves are not enough to be discussed as art. In today’s exhibitions, however, “artists” seem content to call an arrangement a composition. Too often do we witness artists succumbing to this inertia of false self-satisfaction, calling a combination a creation. The difference between experimenting with a role and abusing an appellation lies in how the composition of materials has been constructed. Oh Min says that composition is “a process of defining relationships between the materials within the frame of rationality within a complex activity of accepting numerous variables. Composition comprises all large and small conceptual or actual relationships forged between the expanded materials within the expanded form, including the acts of choosing and deciding to form such relationships. It is about defining the movement’s relationship between the creator and the material that does not cease, not knowing where it is headed. Composition is a collection of motility that encompasses the entire selection process of creative work.” What choice, then, do we face when confronted with artwork that is a collection of such uncertain motility?

What Do We “See”?

“I imagined a sock that, as it was being taken off, had been turned inside out;

but only in part, for its inside and outside to be seen at the same time.

I also supposed there was a constant motion that, in fact, stayed put in its coordinates. Meanwhile, I thought of a tree in a garden too, trimmed in such a way that it was difficult to distinguish the parts untouched from those that were cut. Inside and out; before and after; natural and artificial.

I pictured having two independent things in a state intertwined with one another, so complicatedly, intricately, and neatly that attempting to distinguish between the two becomes meaningless.”

— Oh Min, Jinan Kang, … 57studio4

Recently, I have often thought about literacy. Literacy has its basis in communicated language that is, in turn, predicated upon collective promise. Hence literacy also impacts how we perceive and think about the world. While language is composed of letters and sensory information, there is more to understanding a language than simply looking at letters or taking in sensory information through our eyes. Reflecting what we see and understanding what we hear signifies that a reconstruction is taking place. Thus, literacy perhaps entails seizing a time in passing and inserting it into the area of understanding. Then, what do we say the difference is between seeing something visible with our eyes and “seeing” what exists or occurs beyond the visible? The latter essentially describes “thinking.” Of course, “seeing” here refers to sensing all vibrations that come flooding in from the world onto our skin. The act of facing time, thus, equates to watching some narrative. More coarsely put, time itself is a narrative, one that is constructed to be apparent and stubborn and discerning between microscopic yet massive discrepancies. And our way of understanding the nature of this narrative determines our way of perceiving time.

The creation and understanding of a narrative require many abilities. We must recognize that time flows in its construction while also connecting between the before and after, as well as the inside and outside, by mobilizing all our memories and imagination. When these connections are made smoothly, we regard their result as a conventional narrative. For example, we are very quick to grasp the narrative of pop culture. It is familiar and predictable when it comes to creation and reaction. However, there are times when we have to mobilize everything, including our perception, cognition, reflection, knowledge, and imagination. For Oh Min, a narrative signifies “a flat structure and flow of time” and a texture “a vertical structure and synchronicity of time.” Viewing Oh Min’s work is a process of confronting a mass of such narrative and texture as one solid world. In this world, therefore, there is an immense difference between “merely existing” and “existing while seeing.” Such a difference depends on the sensing individual. Because seeing is equal to constructing in this context, Oh Min’s “synchronicity” can be seen as being constructed in reality and disintegrated by the sensor. Disintegration, thus, means reconstruction. The processes of remembering what we see, anticipating what we will see, and constantly slipping away from what we see are all open to infinite possibilities.

Impossible completions and open decisions

“There is a coexistence of two concepts in Études: ‘practicing’ and ‘ending.’”

— Oh Min, Études5

Oh Min once made a point of saying that “the opening of an exhibition does not necessarily denote the completion of the work.” Artists are often asked to determine the completion of their work, whether it be painting or sculpture. How do they know when their work is complete? Often it seems that they judge by their “satisfaction” and sense of “sufficiency.” For Oh Min, however, the word “completion” seems to be a synonym for “variability.” It should be noted that Oh Min decided to call her “video” work a “time-based installation.”

Video works are fundamentally limited in duration; they inevitably need to be constructed within a specific timeframe. But Oh Min’s construction does not focus on the arrangement of images; instead, she focuses on “movements” and “changes” that generate image and sound. Therefore, describing her work as a video, a very generous grouping of a medium, falls short. Further, defining the work as a “time-based installation” also considers that time, as the construction’s content and format remain the same, while its physical installation takes new forms in each of its displays. Furthermore, if the work is time-based, the completed work would naturally indicate time as arranged in space.

The series of works conceived from “études” also reveals the artist’s notion of completion. An étude refers to a simple piece of music made for practice. It is a textbook for helping performers practice their techniques and a piece of music in its own right composed with a high level of artistry. According to the artist, a performer would select challenging parts from the entire score and practice them in tempo, rhythm, and accents different from the original piece before going back to the original interpretation. Through such practice, all senses, cognition, body, and sound surrounding the performer change, and the performance edges closer to the essence of music. Here we must ask what the difference is between practice and completion. Does time distinguish them? Time is never practiced; it concludes newly to infinity. We all live without giving much thought to every concluding second, hoping that these moments “accumulate” to reach some sort of completion. However, such an idea is closer to an illusion. Practice means many completions. In other words, a time-based installation can be deemed complete only in the sense of being a temporary original copy that perpetually delays the realization of the possibility of permanent completion that it possesses.

In an interview, Oh Min said that “time is ironic.” Time both generates things and makes them disappear. The here and now thus becomes a perpetually unreachable point as soon as it is met. Then what does a music score, which essentially records a performance’s organization, order, and method of execution, complete? What does it make possible, and what kind of incompleteness does it forewarn? What does it mean for a score to be generated after time passes, instead of being prepared beforehand to instruct the time to come with its content and format? If it is possible to have a score that behaves as alive, confounds our initial questions, forces us to revert, doubt, and reflect, what does that look like? What if a score is no longer based upon shared rules, no longer instructs us not to deviate from its interpretation? What happens when a score, instead of being a crystalized perfect record, follows the principle of constructing a here and now that allows infinite interpretations? Here, we must take a closer look at the question posed by Oh Min.

Excellence of a Question Total

A question is valid when it does not hint at an answer. Although we anticipate an answer when asking a question, the act of questioning helps us broaden our thinking. Therefore, a good question behaves like a stepping stone that provides us with perseverance to explore the minute differences between reflections. It is also a firestarter that makes us passionately enjoy the friction created by those differences. A question, therefore, holds our thirst for what we have been curious about, as well as a response that can be predicted based on our

not-always-accurate knowledge. It is also interesting to see that a good question already has an embedded next question. Can a question, then, become a classic? Is there a question that can remain valid for hundreds of years and withstand the test of time?

Interestingly enough, the questions Oh Min poses are found far from a mechanism of advancement or development. The questions imbued in each of Oh Min’s works stay in the present in that they do not necessarily lag behind those of the past. Of the questions she brings forth through her works, none have been resolved and discarded. Depending on the materials used, their relative placements, and the kinds of practice incorporated in each of the artist’s works, the key questions differ starkly from one another. However, it is not difficult to compare one work’s questions with another’s. Her questions thoroughly contemplate the many branches of possibility that are entailed before a generation takes place. Questions that reexamine various factors found in the performance art itself, the difference between musical and dance performances, and the distinction between producing performance art and producing video works led her to ask whether a “time-based installation” could be made as a performance. These questions are not fragmented, but made whole through their differences and repetitions.

Oh Min’s questions make us contemplate the origin, but they do not lead to the birth of the universe or some kind of agnosticism. Her thoughts on relationships pose questions about the close connections between objects while also recognizing their relative independence. And this relative independence opens space for abstraction. The fact that everything changes does not necessarily throw one’s doings into the shade. Rather, does it not allow us to argue, struggle, discuss, and explore amid all the changes related to the here and now due to our willingness to invest time and space to gain reflections generated between changes? Assuming that we need to consider “questioning” for the next 30 years, what notions of questioning will we obtain? How far can we take thinking? Up to what level of detail can we examine? Integrated awareness and detailed discovery sustain each other. Like that one book we thought we had read enough times but end up encountering phrases that appear new whenever we open it again, Oh Min’s works are joyful in themselves for rediscovering questions.

Highest State of Alert

“In my videos, often seen are practitioners who seem to sit still.

But in reality, nobody ever just sits still.

Most of those cast for my works are trained dancers and are seen acting out an intricately composed score.

— Oh Min, from Oh Min: Invitee, Attendee, Absentee (2020).

There are times when we can hear but not see what is moving or who is practicing in Oh Min’s works. It is possible to witness the practitioner engaged in practice, seeing, listening, and thinking in the same space as the moving object or person. As the artist said, everything is composed very intricately. Then where and how is the artist positioned in Oh Min’s artworks? Since Oh Min regards music performance as her mother tongue, does she weave

herself into her work or put herself outside it? Her works range from films and live performances, and she is always engaged in some type of practice. She often cites a choreographer as an example; the choreographer who created the performance is the one who enjoys the performance the most. Following this example, the person who can enjoy Oh Min’s works the most is probably Oh Min herself. As the artist, she is positioned to sense the most minute differences, and also differences created from repetitions. Regardless of the relationship between the artist and her artworks, Oh Min’s physicality and reflection go between the repetitions of here-now and never stop.

The same goes for the audience. Through a single channel or more than two, the number of ways to view her work can be amplified into the infinite. Things happening inside the channel, things that can only be identified with the channel, and even the conditions of the venue where the channel is installed become time that occurs for the first time every minute, every second. Additionally, the channel here is again divided into a channel for projection and a channel for sound. This is because different viewers see the works differently. More specifically, the factors of seeing, hearing, and thinking change with the situation. In other words, that nobody can see the same work in the same space and time puts Oh Min’s here-now in a unique status. At the same time, the habit of trying to identify the visual origin of a sound or story while looking at images sometimes hinders enjoying the art. It is almost impossible for everyone to know everything simultaneously, especially when an artwork is constructed from various directions, colors, focuses, distances, balances, textures, noises, speeds, sounds, orders, patterns, counts, gestures, expressions, thoughts, and memories. However, we might have a chance if we see it many times and practice viewing it. At some point, the viewer’s body should enter a state of alert. And training in viewing, attempting the impossible, transfers the viewing of the artworks into another dimension.

Connecting to Oh Min’s here and now, which creates newly constructed time within the entirety of time, is simple yet complicated. Once one attempts to access multiple here-nows, the most urgent and the clearest here-now make one present in the “highest state of alert.” Therefore, putting Oh Min’s art into words makes one wonder whether it has to attempt to write each and every time-space with its infinite possibilities or just transfer time-space itself as one mass. The experience of existing in the awakened state is multi-dimensional and intense.

Closing

With the 1990s as the turning point, the art world has come to focus on the “topic” of newness. While exploring various theses and global issues, today’s art world’s “newest” topic seems to be the factors related to “justice, righteousness, or equality.” There are only a few ambiguous positions that artists can take: becoming a public whistleblower by visualizing social issues from an artistic perspective, persuading people to apologize for their human-centric attitude, or immersing themselves in contextualizing the subject of creation by borrowing from trendy topics of the time. This is why people tilt their heads in doubt; the “topic” seems to change only every three or four years. It is relegated to a mere tool to make people think they are a part of “the new trend” rather than ingredients used by artists for reflection.

How does someone’s conviction gain trust? Inevitably, an artist can work for only a limited time; her artwork can flourish while she is alive or be appreciated after her death. An artist’s true ambition cannot be bound to her time. It takes at least one hundred years to be considered a classic. Therefore, the artist’s question should not be in the here and now. However, today’s art seems to have embraced being a selfless response made to satisfy others’ expectations. An artist’s original questions are quickly replaced with questions seeking the approval of others. Have we entered a timeline in which the existence of art has become the most precarious? So that the most political and the urgent here and now is, in fact, the here and now missing from such questions? It seems that Oh Min’s following questions already started to emerge a long time ago.

1 “Every art (technē) and every way of proceeding (methodos) are thought to aim at some good.” Aristotle, “Book I, Chapter 1, Good as the Aim of Action,” Nicomachean Ethics, trans. Sang-jin Kang, Jae-hong Kim, and Chang-uh Lee (Seoul: Gil, 2011), 13.

2 Ibid., 14.

3 Theodor W. Adorno, Aesthetic Theory, trans. Seung-yong Hong (Seoul: Moonji, 1997), 245.

4 Min Oh, Sungwan Kim, and Yeasul Shin, Jinan Kang, Yeonwha Kong, Minjung Kim, Sungwan Kim, Kitae Bae, Sulki & Min, Yeasul Shin, Jinyoung Shin, Woosup Sim, Min Oh, Sanghoon Ok, Minsung Lee, Sinsil Lee, Yanghee Lee, Youngwoo Lee, Taehun Lee, Hyewon Lee, Taesoon Jang, Kwangjun Jung, Joseph Fungsang, June Moon Kyung Hahn, Yunkyung Hur, Sungjin Hong, Chosun Hong, 57studio (Seoul: Specter Press, 2019).

5 Min Oh and Jihye Chang, Études (Seoul: Specter Press, 2018).

Critic 3

The light that reveals shadows

Shin Yeasul (music critic)

Olivia1 was deep in thought. At times, she escaped from her thoughts into the scene before her eyes. The cameras hanging from a crane, attached to a dolly, in someone’s hands—all faced Olivia. She returned to her thoughts and, for a fleeting moment, acted out the motion of thinking before she started to sing. Vibrating her vocal cords, Olivia hummed. Although her mouth was shut, the sound leaked out of her body. Here, Olivia thought once more. And in synchronicity, everything was in motion.

Though the cameras faced the same direction, they managed to catch scenes that differed subtly in nature. Depending on the ways they absorbed light and color, their speed of focus, and the object or body they hung from, the scene and movement the cameras were mediating changed. These cameras moved constantly, as if to align themselves with an angle that would glean the best shot. They would focus on Olivia before bringing the wallpaper behind her into clarity.

The wall shifted from time to time. It would keep its place for a while before suddenly changing spots. Pasted onto a faux wall, yellow wallpaper seemed to quiver with vivid patterns. Three kinds of wallpaper had been prepared that day, and the wall behind Olivia would suddenly change patterns on a whim. All three wallpapers sported vibrant colors and patterns; depending on the lighting, their entire aspect changed.

The lights continued to change color and position. They illuminated the subject and wall in hues of peach, brown, and other colors as they lit up the face, revealed silhouettes, or halved the face with their brightness. These lights moved of their own accord, refusing to blend into the scene or become part of the person. In this domain of synchrony, where all things moved in tandem with one another, lights too continuously shaped color and form. In all likelihood, this was the light’s process of finding the balance in everything.

At first glance, the four subjects of Heterophony of Heterochrony—namely, Olivia, the cameras, the wall, the lights, and all that surrounded them—seemed to be occupying the same time and space. But the more the movements of these four subjects through the five-channel video and eight-channel sound installation were scrutinized, the more doubts arose. Initially, the work came across as the same scene observed from many different angles. At other times, it appeared to be different observations taken at different times that just happened to be arranged concurrently through several channels. The occasional humming was at first understood to have been recorded when Olivia filmed on camera. But at some points, Olivia’s appearance on screen and her humming seemed not to coincide. Time did not flow linearly here. No matter what, it was twisted and tangled up in some way. Familiar acts, nothing out of the ordinary, aligned in unexpected ways. Everything seemed to unfold in synchrony, only to become a jumble of the past and present. What was seen and heard seemed to exist on entirely different planes of time. Repetitions could be told apart only ambiguously, whether they were facsimiles of the past or a present separate from the past. Here was a chain of deviations in time. In this realm where curious, undefined perspectives intersect, a question emerges: what on earth do we call this arrangement of forms that move of their own accord?

Key-word

The word heterophony is almost the only keyword to my unlocking the secrets of this work. It combines the roots hetero-, meaning “different,” and -phony, meaning “sound,” referring to a specific state that takes place in music. While the term itself is obscure, we easily encounter the situation in our daily lives—for instance, when two people are most definitely humming the same song, yet the resulting sounds are quite different, or when a person changes part of a song while singing in unison with another, but they’re essentially singing the same song. We call this state of entanglement heterophony, where we alternate between the same and different in an indefinite, flexible manner.

There are, of course, other “-phonies.” Several concepts in Western music, beyond heterophony, refer to the ways voices intertwine, such as monophony, homophony, and polyphony. Monophony involves a single voice or melody. Homophony is a form based on chords, where a single voice comprises the main melody as others stack upon it in harmony. Polyphony is when multiple voices sing their own melodies independently and come together at various intersections. The main differences are whether they have a single voice or many, and how these voices are prioritized within the score.2

These concepts evoke the following imageries: monophony as a single, moving line; homophony as a castle wall stacked high with bricks; polyphony as a group of straight parallel lines connected by a few perpendicular lines; and heterophony as both a line and a mass of tangled threads. While monophony, homophony, and polyphony are relatively easy to visualize, the form of heterophony is hard to define. This is because heterophony is composed of the “same-but-different” or “different-but-same” elements. Depending on where we stand, heterophony can be seen as a search for “similarities” within differences or “differences” within similarities. This is subject to constant change, contingent on the relationship these subjects create in a heterophonic state.

Consequently, the main interest that heterophony presents is not limited to the entangled voices on the surface level but extends to the “relational state” they create, which at times confuses the audience. Subtle movements that tiptoe the line between what is the same and what is different, voices converging towards the goal of sameness or diverging from sameness to a state of difference—all this can be found within the state of heterophony. The dissonance these movements and voices create between sense and cognition questions when a sound can be considered the same or different.

The problem is that Oh Min’s heterophony is not limited to sound. It is not even as simple as substituting another subject for sound or replacing sound objects with other objects. Instead, a type of phase inversion takes place. In music, heterophony refers to a state where different voices commingle and tangle within a definite time range. Thus time acts as a condition and scope, not an ingredient needed for creating a heterophonic state.

However, the title Heterophony of Heterochrony pronounces that heterogeneous “times” compose the state of heterophony. My explanation presents a “tangled line, or mass, of times that are either the same or different.” Then how does time, rather than voices, entangle? How should we understand a mass of time, rather than a mass of voices? Why do times come together in a heterophonic state? In the usual sense of heterophony, the audience identifies the similarities and differences between the individual melodies and traces their relationship. Heterophony of Heterochrony, on the contrary, allows the viewer and listener to sense the similarities and differences between times and trace their relationships.

The Structure of Time

Once again, there are four subjects: Olivia, the cameras, the wall, and the lights. Each assumes a choreography they all perform simultaneously. It takes each three full minutes to complete. While the movements of each subject remain independent, those three minutes can be divided into five segments by the moments when these subjects “collectively change.”

a. Olivia looks at something. The cameras advance towards Olivia. The light illuminates her silhouette. The wall remains stationary.

b. Olivia moves. The cameras gently retreat, only to advance on Olivia once more. An additional light illuminates Olivia’s face. The wall remains stationary.

c. Olivia thinks. The cameras repeatedly change positions, moving up, down, and sideways. Another light is directed at the wall, changing colors at short intervals. The wall moves a little.

d. Olivia hums. The cameras gradually become fixed to a spot. The light gradually fades. The wall moves to the left.

e. Olivia faces the filming crew, moving spontaneously. The cameras alternate their focus between Olivia and the wall. The lights create shadows on Olivia’s face. The wall slowly creeps to the right.

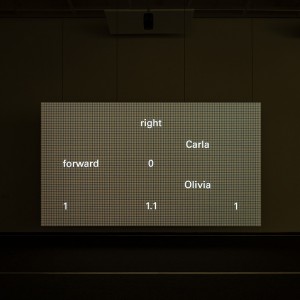

The actions of these four subjects intersect and co-occur. If the three-minute sequence were the work in its entirety, it would have been more closely likened to a “four-part polyphony” than to a “heterophony”—but what happens next is crucial. In Heterophony of Heterochrony, the sequence repeats five times in subtly different conditions. Among the five-channel videos, the difference is most clearly indicated by the circles below (*note to editor: this needs to be coordinated with where the figure is placed in the text).3

The installation structure of Heterophony of Heterochrony

If I understand correctly, the following major conditional changes occur in each iteration as the three-minute sequence repeats five times (these may be completely different from what others identify):

First, three cameras simultaneously unfold the scenes they have captured concurrently. Second, one camera simultaneously unfolds three different takes of a scene.

Third, two channels show a scene taken simultaneously, except for one channel that offers a take from a separate time.

Fourth, two channels of the three showing Olivia switch to two of the filming crew. Fifth, three different wallpapers are shown at the same time.

Here, different cameras may have filmed at the same time, or a single camera may have operated at separate times. Presented are pairs of the same and different timelines, as noted by the appearance of different people and walls. Something most definitely is repeated, yet there also most definitely is dissonance. All of this is rather absurd. No matter which way we turn, there remains something unsatisfactory about our hypothesized explanations. It is possible to consider all the events as independent by neglecting the affinity among them. Then again, to call them repetitions raises the question of how much resemblance—or lack thereof—can be tolerated before something is considered different. Here lies the fundamental question of whether something not entirely identical can be deemed “repetitious.” Where do we draw the line? This question most likely applies to all time-based works that involve repetition.

In Heterophony of Heterochrony, a wide spectrum of moments inspire such questions. I sense a kind of discrepancy within these five sequences. It brings me to a constant awareness that “time,” against its steadfast linearity, is slightly off and can no longer serve as a reliable premise. Things that appear synchronous (同時, at the same time)4 or asynchronous (異時, at different times) continuously intersect. However, whether they are the same or different—things of the past, the now, or entirely new—continues to cast doubts. Why does Oh Min compose such time twists in Heterophony of Heterochrony?

Oh Min’s “Here-Now”

Artist Oh Min has been engaged in the language of visual arts by producing time-based media works based upon having musical performance as her mother tongue. While her works’ themes have varied slightly from time to time, they were all born within a series of questions. These themes were never separate but closely knit together. A few examples are as follows:

The “performative nature” found in the concentrating expressions of the performers’ bodies as well as the filmed media of Marina, Lukas, and Myself (2014); the materials, practice, and exploration of expressions for time-based media works in Youngwoo Lee, Shinae An & Elodie Mollet (2015); the sound relationships reconstructed in the specific language of objects and movement in ABA (2016); the experimentation on the musical concept of polyphony in Five Voices (2017); the composition of audience reactions and facial expressions as materials for performance by distorting the relationship among creator, performer, and audience in Audience and Performers (2017); the study of the scope of practice and performance in Étude for Étude (Dance Composition) (2018), Étude for Étude (Music Performance) (2018), and the serial work Étude (2018); the experimentation on the structure of time and material for performance in Jinan Kang, Yeonwha Kong, Minjung Kim, Sungwan Kim, Kitae Bae, Yeasul Shin, Jinyoung Shin, Sulki & Min, Woosup Sim, Min Oh, Sanghoon Ok, Minsung Lee, Sinsil Lee, Yanghee Lee, Youngwoo Lee, Taehun Lee, Hyewon Lee, Taesoon Jang, Kwangjun Jung, Joseph Fungsang, June Moon Kyung Hahn, Yunkyung Hur, Sungjin Hong, Chosun Hong, 57studio Live performance (2018); the relentless questioning of the genre, media, composition, execution, installation, and viewing approach of the interdisciplinary arts in Absentee (2020), Attendee (2020), and Invitee (2020); and the conundrums surrounding conceptual, constitutive, and performative time as well as the “here-now” in 412356 (2020). Oh Min’s works up until today have come to form a current in serial expansion.

The following concepts, appearing and disappearing repeatedly, have been continuously explored: a work’s materials, the construction of time, the interior and exterior of performance, and the relationship between what makes a work and the “here-now.” And in Heterophony of Heterochrony, these concepts pool together under the overarching theme of time into one enormous whole. A mass in continuous movement, the work has indeed established its own place in itself. Through gradual inspection of its interior, however, we discover newly articulated questions strongly correlated to past themes.

As the term implies, time has been a conditional basis for “time-based media works.” Heterophony of Heterochrony is also time-based and, thus, finds its basis upon time; however, the work employs time as its material more specifically. Namely, the work contains both a conditional time, corresponding to its duration, and a material time, forming its interior. Apart from such experienced time and compositional time, the work also embraces enthusiastic questions about the very concept of time.5

Next, the composition. Heterophony of Heterochrony repeats a three-minute-long sequence five times. Or time is composed by arranging in order five sequences that are similar but somehow different. This construct prompts questions about whether what happens in the work occurs simultaneously and whether it gives rise to a heterogeneous temporality in which different points in time coexist. To deem time a suitable material for composition, the artist would have had to go against the so-called “naturally recognized flow of time” and actively engage in its incorporation.

Then there are the inside and outside. From time to time, the one filming and the one filmed are not readily distinguishable. While some cameras film Olivia, who sits in front of a wall, other cameras film the cameras filming Olivia. At some point, two figures from the filming crew replace Olivia in one channel, and Olivia replaces the two figures in another. As the subjects switch places, the space for simultaneous observation becomes much broader. The inside and outside of the camera, the inside and outside of the performed area, and the inside and outside of the performance all end up indistinguishably intermingled. Notions of the inside and outside gradually blur.

And the relationship. Olivia, the cameras, the wall, and the light move independently from one another. The figure in front of the camera is very likely to be construed as the most important person or “main protagonist.” In many instances, all movements would be instigated by or function for this figure. But in Heterophony of Heterochrony, it is difficult to identify such a clear-cut hierarchy. Subjects composing the work move in their own flow. One element does not overwhelm or dominate another. To me, they seem to pursue the most equal relationship possible, sharing the time and the situation.

Last, the “here-now.” This work, which deals with time, thoroughly investigates the “here-now.” The “here-now” might appear lucid at first glance, but will likely turn murky when synchronous and asynchronous times are questioned; the more one delves into its identity, the more evasive it becomes. Where and when is the “here-now”?6 Up to what duration can we consider “now,” and up to which point can the spatial concept “here” encompass? Observing the installation in which synchronous and asynchronous time, the inside and outside intertwine elaborately, the subject of the here-now begins to feel like an unfathomable duration or size, a mystical unknown.

The people captured in the work seem fully focused, urgently viewing the here-now unfolding in front of them. But in this new flow of time, jumbled among the five channels, tracking down the “here-now” seems rather tricky. The here-now of performative time does seem to exist within the on-screen practitioners’ bodies. In contrast, it is impossible to know how far the here-now of constitutive time can be extended or twisted. It comes to mind that the here-now of conceptual time might have been an illusion, never actually existing. Also, to the audience, who must track all such levels of time in the exhibition space, the here-now of experienced time again becomes as urgent as it was for the practitioners’ bodies on screen. Different times flow on the exterior surface, the inside, the support base, and the outer world of this work. And these times circulate endlessly.

Movement

Everything surrounding this work moves multi-dimensionally, without stopping even once. From whichever part the audience starts viewing, the time and space of Heterophony of Heterochrony are not fixed at a single point. Everything continues in its own flow while crossing everything else. The viewers identify the relationship between these components and become aware of the flow of time as they continue to observe the work. Oh Min says,

“…The beauty of time comes from it producing an ‘invisible image,’ ultimately, through a ‘visible image.’ Whatever the material, as soon as it is placed upon time, it ‘disappears as soon as it is seen.’ Here, ‘memory’ acts as a ‘technique’ that turns this disappeared time into the abstract. The same goes for the acts of creating, practicing, and appreciating. Simple observation is not enough when it comes to appreciating time-based art. The audience must proactively consume its duration, collect sensory materials, remember them, and then, from recollection, abstractly combine relationships among the images to draw an invisible image. Only then does the appreciation complete.”7

Let’s indulge in a little imagination here. What would we be seeing if all these preconditions were reversed? It is most likely that only one shot of the many taken from multiple cameras would remain. A single-channel setup would have sufficed. Olivia’s humming would not have overlapped. The walls would not have moved. The optimized light would not have clung as tightly to her skin or to the wall’s surface. The cameras filming other cameras would have been unnecessary. And we would not have been able to see or hear the people directing the cameras or the scene. The result might have been a solid and complete “here-now.” There might have been no reason for the work to have any duration at all. All of these would have been true if the artist’s goal had been to make a virtual scene orderly, final, and closed. However, Heterophony of Heterochrony unfolds upon time its plentiful movements, which can never end as one fixed scene. As long as there is time, never will its movements cease. And the world where bodies move right before the viewers’ eyes and the world that has been video-edited move differently. Oh Min writes, “Time in film is different from the time of the ‘live.’ Time in film is a rectangle, while the time of the ‘live’ is a polyhedron. Outside the rectangle are many tremendous secrets, but the polyhedron can hold none.”8

There are countless potential worlds outside the rectangle. The sensory information placed in the rectangle is only a very small portion of what happened at the scene. It cannot contain as many multi-dimensional hours or experiences of a polyhedron. Thus are secrets made. In comparison, many subjects enjoy, intersect, and move by their own “here-now” in the time that is “live,” without any secrets. Moreover, this does not solely occur in the “time of the live,” distinct from video, but also in real life, in everything that lives and moves in time.

The way back to the outside world

St. Augustine once remarked, “What then is time? If no one asks me, I know; if I want to explain it to a questioner, I do not know.” It is not only time that comes across as clear-cut yet ends up drawing people into a conundrum. Music and performance, which unfold in time, provoke the same bafflement. The moment one asks what music is, music refuses to be grasped and quietly vanishes. The same is true of performance. A series of events that occur in a time and space involving so many performers does not finalize in a fixed shape. In many instances one cannot tell where the event begins or ends, nor what its scope is. Perhaps it is fundamentally impossible to draw a single, concrete conclusion regarding what happens in time.

If so, why does Oh Min continue asking questions about time? Why does she discover time in its multiple layers or create a temporal structure by stacking them? About time, Oh Min answers: “Time is an abstract concept created by mankind (Leibniz) and a form of intuition of the world (Kant). Because time results from change in matter (Mach), it does not flow without change (Aristotle). At the same time, time also flows regardless of change (Newton) or does not flow at all (Rovelli). If it does flow, its speed is relative (Einstein). The present is the past concentrated (Bergson), and simultaneously, the past, present, and future are mere optical illusions that persist (Einstein). Time can be measured, but it is difficult to know what it actually is. It might be that time does not exist at all (McTaggart).”9 Despite such disparate views, if senses encountering art or the world are not distinct but are in continuous interaction, then contemplating time through art will ultimately relate to the senses of time in general. That is why addressing time is so urgent and significant.

Heterophony of Heterochrony seems to explore a pure inner world, separated from the rest of the world. But upon closer reflection, it is clear that it holds Oh Min’s exploration of time that actually occurred in, and was constructed and experienced in, the real world. The understanding of time and synchrony, as well as the discussion of time and relationships, ultimately connects to an experience of something. There is no fixed scene in our experiences created within time, and the frame’s inside and outside always vary. Inside time, the world does not stop but is in constant movement. And as we observe and experience this, we do not stop. We too are constantly in motion.

Moreover, if this is the essence of time, rather than creating a virtual “here-now” that comes to a single ending, the disparate time in Heterophony of Heterochrony, generating doubt about the existence of the “here-now,” itself seems closer to the truth. Seeing the installation that disjoints time with five channels of video and eight channels of sound, the audience realizes that what “I” see and hear is a tiny part of a picture that can never be completed. Inviting the viewers into a dark room and placing them inside intersecting times, the work enables them to experience the inner workings of the world of Heterophony of Heterochrony. At the same time, the work allows them to experience a method of sensing the world composed of a heterophonic structure. And this is one of the ways that we may understand how the world is constructed, the world where we can have experiences in time.

I do not understand Heterophony of Heterochrony by seeing or listening to something in particular. Instead, I become more fully aware of what cannot be seen or heard. An unknown area, an unseen or unheard area, is more clearly sensed, while the surrounding time and space expands and thickens. Heterophony of Heterochrony reveals the tacit point that cannot be seen or heard by letting the viewers see and hear something. This is just like the very last moment shown in the work’s sequence, when the light actually lands on Olivia’s face to reveal the outer shadow.