MINJA GU

Interview

CV

<Selected Solo Exhibitions>

2018

Inside the Belly of Monstro – Citadellaan 7, Gent, Belgium

2016

Leaking Pipe, Roundabout, Seoul

2013

Personal Reconstruction & Self Expression, Guminja Art Fair, KimKim Gallery at Takeout Drawing, Seoul

2011

Atlantic-Pacific co., Moore Street Market, New York, US

2009

Identical Times, Croft Gallery, Seoul

<Selected Group Exhibitions>

2017

DO IT, Seoul – Ilmin Museum of Art, Seoul

2017

The Great Machine IV, J. Trepat Museum,Tarrega, Spain

2017

OK VIDEO Festival, Jakarta

2016

C as in Curry S as in Seen, Marion de Cannier Art Space, Antwerp

2016

Who’s Who, Waley Art, Taipei, Taiwan/Audio Visual Pavilion, Seoul

2016

Belgium Performance Festival 3, Brussel

2016

Impact Festival: Authenticity?, Utrecht, NETHERLANDSs

2016

Untimely Encounter, Alternative Space Loop, Seoul

2016

Mille-feuille de Camélia, ARKO Art Center – Seoul

2015

Loner’s Guide, Common Center, Seoul

2015

View From Above, BIN, Turnhout, Belgium

2015

And No Matter What The Phone Rings, the 6th Moscow Biennial Special Exhibition, CCI Fabrica, Moscow, Russia

2014

Anyang Public Art Project 2014, Anyang

2014

Home/Work, Audio Visual Pavilion, Seoul

2014

Once Is Not Enough, Audio Visual Pavilion, Seoul

2014

The Part In The Story Where A Part Becomes A Part Of Something Else, Witte de With, Rotterdam

2014

The Breath of Fresh, Gyeonggi Museum of Modern Art, Ansan,

2013

New Vision, New Voices (Young Korean Artists 2013), National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Gwacheon

2013

Our Hesitant Dialogues, Art Sonje Center, Seoul

2013

Republic of the Two, ARCO Art Center, Seoul

2013

Love Impossible, MoA, Seoul

2012

Trading Futures, Taipei Contemporary Art Center, Taipei

2012

The Cabinet in the Washing Machine, Seodaemun-gu Recycling Center, Seoul

2012

Doing, Kumho Museum of Art, Seoul

2012

Community Art, Gyeonggi Museum Of Modern Art, Ansan

2012

Creative Attitude in That Distance, Seoul Art Space Geomcheon

2011

The 10th SongEun Art Award Show, SongEun Art Space, Seoul

2011

About Books, KT&G Sangsang Madang, Seoul

2011

Life, No Peace, Only Adventure, Busan Museum of Art, Busan

2010

Anyang Public Art Project 2010, Anyang

Has the Line Killed the Circle?, La General, Paris

2010

The 10th Seoul International New Media Festival, Seoul Space, Seoul

<Awards>

2010

SongEun Arts Award, Excellence Prize, Seoul, Korea

<Residencies>

2016

Gasworks Residency Program, London, UK (Supported by Art Council Korea)

2015–2016

Hoger Instituut voor Schonen Kunsten, Gent, Belgium (Art Council Korea International Residency Support, Korea)

2011 2011

ISCP(International Studio & Curatorial Program), New York, USA

2010–2011

Gyeonggi Creation Center, Residency program, Ansan, Korea

2008

Hangar Fellowship & Residency, Barcelona, Spain (Supported by Ssamzie Space)

2007–2008

Ssamzie Space Studio Program, Seoul, Korea

Critic 1

With eyes wide open to the world

Park Soo-jin (Curator, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea)

I recommend Minja Gu (1977- ) as a candidate for the 2018 Korea Artist Prize. The life and work of Gu correspond, each confirming the other. Rather than merely handing out an artwork of a specific brand as a whole in itself, the artist enables one to see the world with wide-open eyes by capturing the one-centimeter zones that have not well visible despite its sure presence within the frame of the world and inviting one to look into them. “There are certain frameworks that have been built in the course of a long time and are shared (or seem to be shared) by the members of a collective—in other words, particular ways in which one understands his or her society, the system that is agreed upon or certain ideas. And when my thoughts fall upon the fact that they are intricately connected to one’s daily thoughts and behaviors in one way or another also as the framework for one’s private life, a feeling of dread comes upon me, and that dread serves as a starting point for my works.” The artist’s everyday approach to the macrodiscourses such as the value of labor, the function and role of social institutions and processes and standardized perceptions encourages one to rethink existing stereotypes.

In WINTER-ING (2011) the artist and the viewers shared kimchi and rice showing on the TV screen the video documentation of her helping the residents of Sungam Island, Ansan, Gyeonggi Province for which she got rice and kimchi. As the production process of an artwork is replaced by the process of laboring, this work invites one to speculate on the value of labor. Her photographic documentation, The World of Job shows Gu’s performing the role of a foreign worker as it depicts the process in which an immigrant’s story about the difficulty of finding jobs in Taiwan leads to her carrying around a sign for a job opening on the streets and her finding a job through an employment agency and her working there. In 42.195 (2006) the artist finishes her own two-day marathon during which she walks, eats and walks again instead of running in an actual several-hour marathon race and by doing so 구 voices her defiance against the idea of competition. In The Authentic Quality (2014) the artist reproduces the foods in accordance with the photos of them on their packages and serves them to the viewers. The realization of this project took her about two years as she got a cook license in Korean cuisine. The artist ordered the same bowls and plates as ones in the photos and imitated the colors and shapes very closely, and this substantiation of those designed and intended images reveals the gap between the real and the image. 23:59:60 (2016) captures a myriad of faces of the world at the leap second, which is known to occur every three years. Between 23:59:59 of June 30, 2015 and 00:00:00 of July 1, 2016 is added one leap second. The artists asked people in various places throughout the world to take a picture as directed by her. The Square Table: Public Hearing of the Requirements for the Artist-position Government Official (2013) is of two mock public forums where a public official, an artist, a professor, a magazine writer, a curator and a cultural critic talk about the various matters in relation to the establishment of the position of the artist-official including qualifications, duties, the kind of the department and salaries. This project allows one to ponder upon aspects of social structure such as the roles of art, the system of the government, the employment and salary of young people.

Gu does not scrutinize the everyday life from critical perspectives. Rather she documents in the forms of photography, video and publication her performances in which emphasis is given to intents and processes. In these performances the artist is not a mere observer. She executes them by herself, experiences and shares with viewers. She puts into practice the social function of art to let one see from new, different perspectives. Her way of thinking is based on the humanities which are concerned with what is human. Her work does not involve the evaluation of humans in the criterion of ‘average’ understanding but encourages to reconsider such understanding and value. In the present times when social is pluralized and various social networking services are popularly used as communication means, either the new or the ideological is not the sufficient condition for a work of art. Artists of these days form relationships with and get along with other people as a member of society and therein make and complete their works. Here they encounter the unexpected accidents and discover variable significances, neither authoritative truth nor fixed meanings. Gu does not judge them by the measure of good or bad but accepts them as they are and feeds them into her works of complicated and multilayered structure. Minja Gu is an artist who is capable of stirring up such a discourse, and thereby more than qualifies for the Korea Artist Prize, one of the substantial patronage-oriented art projects in this contemporary Korean art scene.

Critic 2

Thoughts on the Work of Minja Gu

Martin Germann (Senior Curator, Stedelijk Museum voor Actuele Kunst (S.M.A.K.), Ghent)

It was in the spring of 2015 that I met Korean artist Minja Gu for the first time. It was during my studio visit at Higher Institute of Fine Arts in Ghent as a Visiting Lecturer, in a city where I work at the municipal museum S.M.A.K. This scheme is part of those rituals that keep the international art system running: as an institutional expert, you are put in a position to expect a mostly young artist laureate performing his or her work to you, so that you can judge it. Ideally, you judge it positive—to remember and to recommend it further, which is for the sake of the artist, and of course also for the institution that pays you. From that first visit, I recall various projects that Minja told me about, in front of her computer with a screen presentation—because there was nothing in terms of “material” she could show me. Some were realized as her works, some others did not—those were rather sketches hovering in the artist’s mind, waiting to be executed one day. Local consumer stuff stood around, such as pasta noodles, various other groceries primarily of Belgian supermarket brands, some beer cans—but nothing could be immediately considered as “art” in a traditional, commodity- oriented perspective.

But I remember other parts of that visit more clear. Minja told me that she had already been in Ghent for four or five months. Of course, I asked about how was her use of the time at the residency by then, and what it would be in the near future. She then told me that she still didn’t yet know what exactly her project in the upcoming months might be. I remember being very impressed by this candid answer. To extend her response, she expressed a vague interest in the infrastructure facilitating the city (as in every city), as well as statistics and information of all kinds, from the register of the local population to product palettes at local supermarkets. In a way she articulated that everything between the particular and universal that is guaranteeing life to be as fluid, secure, and free of obstacles as possible would be of interest to her—almost in the sense of common rituals structuring our daily routines. But no real strong focus in the usual way regarding her project seemed to have arrived yet. And while camouflaging hesitation in this very discrete manner, Minja was actually working already.

What I found remarkable about this encounter was not so much how she claimed to be searching for the right thing to come, because we know that the force to realize permanent reinvention is one of the many challenges of an artist’s life. I was rather intrigued by Minja’s security towards her pace of working, which on the first impression felt like a misuse of time—or, leaving standardized morals about work left beside—like a different yet very self-conscious way to think about her own (artistic) production, and in the same fairway on production as such. Minja seemed to have an uncorrupting insistence on is how she was going to use her subjective time, and what that was. By looking closer to some projects the artist has materialized in recent years, one realizes that this attitude is necessary, because she never works on singular pieces, objects, artefacts. Rather, her working field lies in the tracking of larger contexts of meaning or situations, which she then— with a couple of gestures—choreographs or personally fills in as or with “art,” and from the moment of activation those situations produce their own material or gestural outcome. One could mention here, of course, the marathon she was walking within two days in 2006, or the self-imposed task to find a job in Taipei to follow a blueprint of an aboriginal woman’s biography that dates back 40 years in 2009, with a plain and uncomfortably witty title World of Job where the artist fulfilled all tasks one had to do to find a job, so that the border between art and real life could be evaporated. One of those works which obviously has already been in motion when we met in her studio in 2015, was exhibited in the usually private setting of her apartment in Ghent in the beginning of 2018, with a particularly non-discrete title Inside the Belly of Monstro.

The information about the exhibition again indicated nothing else then when Minja Gu had arrived and left Belgium, including all exact entry locations and data in 2014 – 2016. The exhibition itself consisted basically of—almost—all the remnants of objects Minja has consumed, used, touched, in one way or the other—from the exact moment she started and ended her residency at HISK. The work, including the publication, showed various stages of her apartment slowly being filled up into a gargantuan yet elegantly sorted a collection of remnants of all kinds. It was nothing else than a veritable portrait of the artist’s time of two years. By sorting and indicating all those natural and artificial objects, things, and rubbish – let’s leave all culture behind and call it “material”—in the same archeological manner, almost no difference was made between the things – everything was treated similarly, in the sense that it was kept: Piles of empty egg shells, small branches without raisins, little sticks to eat French fries, fag ends, emptied fruits, and plastic bottles – literally everything one uses for daily life was present, but in a certain way as a negative space of time’s flux. In some images in the catalogue, arrangements and constellations became visible in a way that the artist tried to realize. Those evoked certain object poetry, but the idea of classification was, at least in my opinion, not the core of her practice. Those attempts, the underlying wish to produce a decisive “form” and meaning, pointed rather in an indirect manner to usual expectations on art, and from there they were able to emit a poetic pointlessness. If we would put her project into lines of artistic predecessors and would think of, for example the unavoidable Marcel Broodthaers, we could state that Inside the Belly of Monstro created a giant accumulation of shells through which the many exchange economies of life were executed— embedded within two other shells: the private environment in the sense of a “living space”, and the bespoken two years of time in the sense of a “duration”.

While thinking about portraiture, it might make sense to jump to that particular medium where Minja’s practice is, at least from an academic perspective, grounded in: painting, a subject that she studied at the art school. But most probably the representing capacities of the two-dimensional plane were not sufficient for both the motives and also the motivations of the artist. Minja’s idea of painting—portraying a poetic realism of the contemporary life while remaining in life—turned from the beginning into the social space. Because what she was portraying in Inside the Belly of Monstro was, as we saw before, something as simple as plain duration. But those remnants also posed questions such as: How do you use the systems that hold you, direct you, manage you, and keep you suspended? How wide apart do you like the bars of your cage? Apart from their function for the everyday these objects lead inevitably to questions of control and desire, security and freedom that can easily be scaled from the micro-nuances of the intimate everyday life up to international geopolitics.

But the particular way Minja Gu’s work functions is leaving the tracks of a simple critique on consumerism and possession. Instead, it goes deeper into the viscera of contemporary life. This is exactly because of the position from which she takes on the role of an artist. It is, in fact, the opposite of any idea of position, which is usually articulated through language, a tool to apply for each artist seems to be necessary and unavoidable. But the artist’s practice is obviously not bounded to any kind of language connected to the myth of the artist’s hand. Rather, the opposite is the case: the purification of each of the —necessarily—few projects she realized in require each their own “language,” but each time closely connected to the particular specific environments and surroundings with its capacities, rules, and norms. Those were activated and transformed to provide an artistic vocabulary. Now, more than three years later, I am invited for the second time to write on Minja’s work. It happens once again in a ritualized scheme, but this time the artist is nominated for the Korean Art Prize, which is an honor for her and great to hear for me, since I have trust in the artist, and am chosen to comment.

This time, I am not visiting the artist: She is realizing a project for her exhibition by herself. I am trying to reach her to speak with her about the plans, but I cannot do so. The reason: Minja is realizing a project she had already told me in 2015, which, again, deals with time, and then, logically, with space. The performance she is preparing brought her to the Taveuni on the Fiji Island, exactly to that part of the world where an ultimate division physically takes place: The International Date Line (IDL) is running exactly through that archipelago. In a physical distance as thin as a piece of paper, the distance of time, the invented currency that makes our world running, is almost endless, like 24 hours. This paradoxical spot, since so many dreams of different kinds culminate there, raised not only the interest to many tourists worldwide, but also a certain interest to the artist, to use this strange yet culturally coded phenomenon for a performance, which basically consists of a trial to live the same day twice. It is a performance that uses the imaginary potential of the place— even on Wikipedia, the IDL is described as an “imaginary” demarcation line—for something impossible.

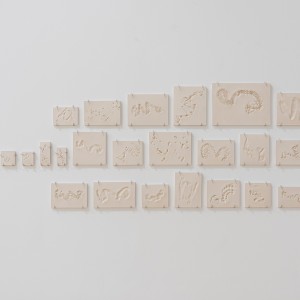

Basically, the work consists of the execution of this performance, trying to live the same day twice and later on a presentation of its various parts, from the tools to film materials, in the museum. What she needed was a second person to take on the role in the mirror image, a film camera, instructions, rules to choreograph the day, two sets of the same everyday objects she borrowed from the place, two tents, food, and the possibility to prepare it—the world as a twosome. But, as the asymptote in mathematics will never touch the line it approaches, to live a day twice remains an impossibility. The performance, or rather, its documentation, is gently presented in the museum, with an installation consisting of various materials built in the museum with its architectural particularities: a ventilation shaft on the floor was used as the demarcation line for a split or mirror image presentation of the different sets of objects. On a row of museum walls, photographic slices are glued, showing the exact perspective from the IDL 180 degrees in Northern directions, vitrines with the T-shirts worn by the performers, quoting On Kawara’s historical exercises in a dry and funny way, the plans with exact instructions, many photographs from both sides of the IDL, as well as, necessarily lengthy documentary of the 48 hours of the two days—since it is captured and presented in a real-time length—with the performers next to each other, each in another day. And then, finally, there are some objects presented. The objects are, once more, just shells—hollow castings of things the artist found in the other day, again, no objects, no shadows neither.

Vasif Kortun once described attributes such as ‘frail,’ ‘intimate,’ ‘grace,’ ‘wit,’ and ‘poetry’ as key qualities that come into mind when thinking about Minja’s work, and, just as she does with products, statistics, and standards—I am appending my opinion to an existing judgment. By the way, wasn’t it Douglas Huebler who once formulated this famous sentence: “The world is full of objects, more or less interesting; I do not wish to add any more. I prefer, simply, to state the existence of things in terms of time and/or place.” It seems as if Minja took Huebler’s wise sentences from the 1970s as a genuine point of departure for her performative trail through the objects and social relations that exist in the world: the certainties of our daily lives that Minja steadily confronts with their blind spots, so that her work reminds us that everything is fluid.

What makes her work really unique and cross-cultural in the best sense is its combination of both a laic and Kafkaesque equanimity towards the endless course of things versus the invaluable, undeniable value of a singular moment. And it is exactly this nexus of Western and Eastern thinking, of pure teleology and pure presence what her work is balancing. One might think of artistic predecessors, such as for example Tehching Hsieh or the yet quoted On Kawara, who also used time as a working material, artists, whose practices are based on the futile grounds in the Conceptual Art histories of the 1960s and 1970s. One has to admit though, that quite literally, times have changed. Art is urgently searching for its function and its place, in a world that is increasingly shaped by issues of separation, polarization, and reduction. The symbolic space which, at least in a Western Modernist idea, art was filling for an idea of “The Other” does not exist anymore. Minja Gu is certainly applying those recipes, but within a world that has completely changed, accelerated, and globalized since then. In this sense, her slowness might be a key strategy—not to surf on the waves, but resist the waves. The combination of this slowing tactics with the old—or even eternal—themes makes her art touching and deems her practice unique.

The commission for this small essay was to write on the theme of “universal empathy” in the work of Minja Gu. And actually I do not really know if empathy in itself is a driving force of the artist’s work. Behind the practices stands some kind of unswerving and incorruptible indifference, which is described as the sheer opposite of empathy in a common reading of her work—on the first site. It is because her bastion of pure artistic subjectivity provides her a capacity for a maximum of withdrawal of any artistic language, prefiguration, gesture, and expression on the other hand. But this maximum of restraint shows us even clearer and brighter sense of the authoritarian, controlling, basically absurd systems that we are implanted to live in, which navigate our dreams and our desires. The position where Minja’s work is speaking from is not any utopian outside nor does it point to anything “better” from a superior perspective. Rather, it speaks from the most casual and common inside of human coexistence. This strange capacity of Minja’s work is then able to produce something like empathy, an almost emotional glimpse that we are not but always alone, right here and right now. With the strategy of the snail, or, as a famous German artist once said: “The avant-garde of today is running after.”

Proof-reading: Park Jaeyong

Critic 3

Our Past Is His Future, Our Future Is His Past

Hye Jin Mun (Art Critic)

I

A place where yesterday becomes today and today becomes yesterday. Island of the Day Before, Island of the Day After (2018) reminds me of a science fiction novel that I read a long time ago. In this story, an astronaut who was accidentally sent to the distant future struggles to return to their home (and to the time they belonged to), and in the process encounters the moment where their trajectory and Earth’s orbit intersect. At this moment, the astronaut is able to touch the ground and see other people who are looking at them, but since they belong to different times, they are unable to communicate. Every year the astronaut make an appearance in the present day, though they only pass through our time for a short while. The time before the Big Bang, which is in the past for us, is the future that they will return to; meanwhile, our future is the past that they have already been through. The time of their appearance also continues to change in the time of solar system.1

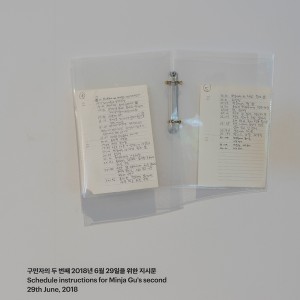

While some may think that time travel could only exist in a fictional world, it does exist in reality. Island of the Day Before, Island of the Day After is a 4-channel video about the International Date Line (IDL) of Fiji’s Taveuni Island in the South Pacific Ocean. With this imaginary line acting as a central point, the area immediately west of the line is a day ahead of the area to the east. This is the place where you can go from yesterday to today and vice versa with a single step. In the video performance, this strange coexistence of spacetime becomes embodied by two performers, who respectively spend 24 hours in the area to the west and the east of the International Date Line; each performer spends a day from 12 midnight to the next midnight on one side, then swapping locations to spend another full day on the other side. More precisely, on the first day, performer A (Minja Gu) exists on the west side on June 29, 2018, while performer B (Soojung Choi) is on the east side on June 28; performer A, who moves to the east side on the second day, lives the 29th once again— because a day has passed from the 28th to the 29th on the east side—while Performer B who moves to the west, goes directly from the 28th to the 30th (See Table 1). The result is that the same day (the 29th) is repeated twice for performer A, whereas the day of the 29th is lost for performer B. This situation is recorded in the 4-channel video shot continuously during the periods of the 29th/28th and the 30th/29th. The repeated day is represented through performer A’s actions, which mirror their actions of the previous 24 hour period, and the lost day is visualized in the daily necessities for a day’s use that are unused and left.

II

“What would happen if someone could live a certain day twice, while that same day does not exist for others?”2 This philosophical question is lived as an ordinary day—one that is not particularly different from any other—by the figures in the video. The performers do not do anything special. They have three meals a day, sleep, clean up after themselves after eating, and spend their spare time reading or walking around. These are daily activities focused literally on “passing the time” (according to the artist.) Sometimes tourists who come to see the date line sign appear in the background of the video, but they are not concerned with, nor do they make any intervention in, the activity of the performers. However, invisible boundaries and the distinction they make implicitly pose restrictions on the actions of the performers. They do not cross the virtual date line to go to the other side. They separately go about their daily lives, as if they do not know the other exists. There is also a distinction between the repeated day and the missing day. In the case of performer B—who skipped from the 28th to the 30th—the missing of a day does not lead to any visible change in actions, but performer A—who lives through the 29th twice— repeats her actions from the previous day.

Island of the Day Before, Island of the Day After recalls the practices of two art historical precedents who both equated art making with the daily processes of living life, and whose work often functioned to archive life: On Kawara and Tehching Hsieh.3 Since 1966, Kawara created date paintings of almost every day, continuing the practice for 50 years, while also rendering his daily activities into an enormous accumulation of recordings of the places he visited, the things he read, and the people he met. Hsieh equates the artistic practice to the “embodied time that is lived in person,”4 imposing constraints and conditions on his life and performing them in “Lifeworks” created between 1978 and 1999. Although there is no direct association between the works of these two artists and Island of the Day Before, Island of the Day After, some parts of it do evoke Kawara and Hsieh. In addition to the fact that the artists perform the task of recording as performers of the work, Gu’s work surreptitiously calls to mind humorous parodies of the predecessor artists in its way of making the performers and the viewers aware of time. For example, the performers paint the date in their location on a t-shirt at the beginning of the performance, and there are newspapers that are delivered in the middle of the performance, naturally evoking Kawara’s Today series (1966—2013). Additionally, the actions of Minja Gu, who repeats the same day–struggling to record every action while reading, eating, and sleeping on the first day and attempting to replay them on the second day–resonate with Tehching Hsieh’s second year-long performance Time Clock Piece (1978—1979), which attempts to synchronize organically-flowing biological time with the standardized mechanical time of a time clock.

However, in its intention and methodology, Island of the Day Before, Island of the Day After contains many different layers than the works of the two preceding artists. Compared to On Kawara’s performance where rigorous and systematic methods of recording are crucial, Minja Gu’s performance is relaxed and more human. Whereas persistence and accumulation hold significance in the Today series, Gu’s work is a short-lived, one-off piece that lasts only for two days. In particular, the nature of the time manifested in Gu’s work is crucially different from that of Kawara. Kawara’s time is not the kind of time that measures the lived experience of an individual. Instead, it is “an accurate and pure segmentation of measurement,” as well as a consideration of time as a pure abstraction that is “homogeneous and empty.”5 On the other hand, in Minja Gu’s time, the emphasis is inversely placed on the empirical temporality that the performers experience rather than a mechanical view of time. Also, unlike Tehching Hsieh’s commitment to complete all of his actions (including sleeping) within the bounds of a mechanical time in order to record the time every hour–and represent a “physicality that is being trained to the capitalist notion of time”6—in Gu’s performance, it is more important that her actions slip out of an accurate repetition.

The time in Island of the Day Before, Island of the Day After is not an abstract time that excludes the individual. What it reveals is the disparity between standardized time and empirical time, rather than the manifestation of the absolute time. The central focus of this performance is to show that an artificial segmentation of time is arbitrary, and differs greatly from the sense of the time that the body actually experiences. The situation of Taveuni Island—whose location, the exact opposite side of the globe from the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, England, allows two dates to coexist in one landmass—is metaphorically expressed through the awkward actions of the performers who pretend not to see each other while they are right next to each other. Though the IDL demarcates the boundaries between yesterday and today, there is no way that an organism’s biological time can be so clearly defined as completely in the past or completely in the future.

The arbitrariness of this artificial segmentation is emphasized through several episodes revealing that the land that each performer inhabits is actually an unbroken continuum: though initially they ignore each other, a moment occurs when all of a sudden the two performers begin to play badminton with the date line between them as a net. Dogs and cats abruptly enter the scene and freely cross the border to get food, alluding to the arbitrary, pointless nature of the date line and the central meridian of longitude that were established by imperial powers long ago. Attempts to introduce system and rules to confine the freedom of life continue to fail. Appropriately, the artist’s performance, which is supposed to function as a repeat of the day prior, is constantly hampered by the forces of nature. For instance, when it is too windy, the performers are unable to go to bed and scramble to find shelter in the time allotted for sleep. Or, Gu oversleeps due to extreme fatigue and fail to wake up at the appointed time.7

Issues that continually disrupt Gu’s plans represent the failure of rational time to control and manage biological time. As long as we are social beings, we cannot escape from the dominance of objective time divided into standardized increments; at the same time, we are still under the influence of subjective time governed by conditions of our own bodies. In Island of the Day Before, Island of the Day After, too, the performers are not independent from the linear time that is imposed by the outside. Every three hours, the performers align their bodies to the direction of the hour hand on a clock, a gesture that reminds viewers that quantitative time continues to flow without rupture while the performers are passing the time. Still, each performer’s efforts to repeat the same actions do not go as smoothly as anticipated, and the gap between the subjective time experienced by performers A and B only grows as the video progresses. Compared to performer A who moves relatively little, performer B often takes pictures and moves around the surroundings much more frequently. Even though the performers are not strangers, and are in fact old friends who have known each other for about 20 years, the differences in the way they experience time reveal the stubborn biological rhythm of two individuals that have not assimilated to one another despite how long they have had to adjust. Here, the external time that is measured and managed for certain causes, and the subjective and experiential internal time of the individual continuously intersect, but they never truly merge to become one.

III

The imperfection of standardized time measurements, different ways of measuring time, and the relationship between measured time and empirical time have been enduring interests of Gu’s even before Island of the Day Before, Island of the Day After. In fact, the majority of her work is about time. One of Gu’s early works, Symposium (2007), was a performance held on the rooftop of Ssamzie Space where six 30-year-old men and women talked about love from 11:05 pm to 11:12 am—from the time when the moon rises to the time of its setting. In this work, the physical time of 12 hours is permuted by the empirical time of the young men and women who stay up all night talking. The objective amount of time—a half day—would feel longer than it really is to someone who is experiencing sleep deprivation, but for someone sharing their innermost thoughts with empathetic listeners, it might feel like a brief instant that is not long enough. The length of subjective time differs from one person to another in relation to their feelings. Identical Times (2008—2009), a work produced during Gu’s artist residency in Spain, is another subjective interpretation of 24 different times that are identically divided. Referencing a clock tower in a public square in Barcelona, Gu divided the city into 24 equal segments and explored places of which location correspond to the direction of the hour hand of a clock at certain times. For example, the artist takes a stroll for an hour at 3, somewhere in the direction of the clock hand at the 3 o’clock position, observing and depicting the things she finds there. Here, the standardized increments of mechanical time are converted into an embodied memory of place for the artist. 24 Hours (2009), produced in a similar period, correlates with performer A’s part in Island of the Day Before, Island of the Day After in that performers spend their time following a certain set of instructions. The dissonance that occurs when the body of an individual is forced to comply with the mechanical time is made much more noticeable due to the rigid rules of this work. Over 24 hours, the performers of the piece adjust themselves to the “Korean Time Use Survey.” They work for exactly 4 hours and 2 minutes, spend leisure time for 5 hours and 5 minutes, and clean up for 21 minutes. The process of conforming oneself to the standards that were set by others causes considerable stress. For example, some performers do not like to cook, but they have to cook their evening meals to fulfill their housework time, and another performers cannot go out to see their friends once they have used up their allotted travel time. The violence and arbitrariness of the criteria called “average” emerge to the surface only when the bodily time of the performers do not match with the ways the average Korean spends their time.

Gu’s relatively recent works 23:59:60 (2015) and Sunset-Sunrise (2017) are direct antecedents to Island of the Day Before, Island of the Day After in terms of concept. They deal with the relativity of time, that is empirically simultaneous but normatively varies. 23:59:60 is about a leap second, a unit of time that is introduced every three or four years to eliminate the difference between standard solar time calculated by the earth’s rotation velocity and standardized atomic time calculated by the unit of atomic vibration. In the work, 68 participants in 24 different standard time zones took a picture of their location at the exact moment when a leap second was added and sent it to the artist. Although it only lasts for a second, the existence of the leap second proves that scientific time is not absolute. Moreover, the moment when the leap second occurs is actually concurrent, but the times indicated on the clock are different. The imperfection of objective time and questions of time differences caused by geographical distance are also dealt with in Sunset-Sunrise. Having been based in Europe for the last few years, the artist has connected night and day in Europe and Korea in order to exchange messages with her friends in Korea. At the summer solstice, when the sunset and sunrise of London and Seoul almost overlap, the artist in London took a picture of the sunset, while her friend in Seoul took a picture of the sunrise for two hours at the same time, with a one minute interval. In the face of this contradiction—that measured and lived experience endlessly diverge—the nature of time becomes increasingly ambiguous.

One question emerges in front of these works that are similar yet seemingly different: Why is Minja Gu so interested in time? Why is the fictional quality of homogenous time so important to this person? The answer can be found in the artist’s first work 42.195 (2006). A marathon is merely an action of running 42,195 km, but the time, capital, and effort expended to win the race are enormous. Gu commented that it seemed strange for her, this competition of speed where everyone runs identically for something that can be pointless.8 In order to find a different speed from the outside, the artist instead walks more slowly. She does that to slowly find a different time, at her own pace. The quiet violence that equalizes the idiosyncratic differences of people, by way of rules and standards made by someone’s point of view either by chance or for convenience, these are the things that drive Minja Gu’s unique resistance. What is particularly noteworthy is her attitude and momentum within this resistance. While the rejection of oppressive standards can be easily found in other artists’ work, Minja Gu’s unique characteristics are revealed in the manner of her rebellion. Minja Gu does not directly attack or explicitly mention her object of criticism. She has not made cynical parodies like Andrea Fraser, nor does she take a form of self-torture to put self into a system, like Tehching Hsieh. Haeju Kim calls her way “a tacit repulsion:”9 a simple yet stubborn resistance to the rudeness of the notion of the average, that which abbreviates the individuality of all people and things to one or two words. Her way is a gentle persuasion that does not force her own perspective on viewers, yet still makes them easily nod through the creation of joke-like situations in which the structure she builds continuously fails so that the authority of the measuring index collapses accordingly.

Another distinctive feature of Minja Gu’s works is that her resistance begins from her personal daily life, not from a rationalistic worldview or a discursive critique of ideology that homogenizes the world. The previous works on time that serve as the basis for the exhibition Korea Artist Prize 2018 are also based on the artist’s own experience: Identical Times originated from experiencing an unfamiliar temporal concept in Europe where, unlike Korea, “daylight saving time” (or “summer time”) is observed, and Sunset-Sunrise began from her experience of trying to find a time slot to exchange messages with her friends in distant places without disturbing the rhythm of their lives. It is a consistent fact throughout Gu’s work that the ideas are born from concrete life experience, rather than from grand narrative. This is especially noticeable in her works of institutional critique, which represent another axis of Gu’s practice. For example, The Square Table: Public Hearing of the Recruitment Requirements for the Artist-Position Government Official (2013) obliquely criticizes the artistic institution that standardizes the art world by replacing a round table with a square table and substituting the free concept of art with the administrative language of public officials, appointments, and public hearings. However, the basis of her criticism here arises out of the daily life of an artist rather than from the abstract notions that make up the institution (artists, artworks, art museums, discourse). The irony of the reality that artist herself is required to become public servants— due to the existence of public funds that are crucial to one’s survival—inspired the creation of this work. Gu & Yang Art Foundation (2013), a work about an imaginary foundation where the artist’s parents serve as chairmen of a board of directors, also exposes a reality of the Korean art world of this era, that a steady artistic practice is often not viable without the support of one’s parents. Minja Gu’s strategy of substituting her firsthand personal experiences of hanging on to life as an artist to the public problems on the level of institution is another form of resistance against the system. Not denying the given conditions, but voicing herself discreetly and steadily, and overcoming intense situations with humor and composure is her attitude.

IV

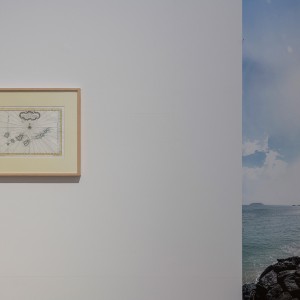

The centerpiece of Gu’s show in the Korea Artist Prize 2018 exhibition is a 4-channel video Island of the Day Before, Island of the Day After, with other small works related to the video displayed around it. The two streetlights placed in the front of the exhibition space are symbols of the sun, which defines the sensations of a day, and they serve as a metaphor for light that is inseparable from the segmentation of spacetime (the speed of light determines the time, and time is inseparable to space). Placed between the streetlights are objects used during the performance. Folded tents, cooking utensils such as pots and spatulas, mats, and camping chairs are displayed in a composed manner. Newspapers, wristwatches, and clothes with dates painted on them are placed farther away. The provisions for June 29, 2018, a day that was skipped over by performer B, Soojung Choi, are also displayed nearby. While these derivative props are scattered throughout this area, the main video is shown deep inside the space. There are schedule tables that were made for performer A to repeat her actions, six photographs capturing the performers’ switching locations at midnight that symbolize the date change, and a negative print on clay plates made by rolling stones, shells, and corals from Fiji on white porcelain clay.

The exhibition is designed to emphasize the relativity of measurement even in the props and spatial arrangements. Evidence that the current date line should not be taken for granted is placed throughout the exhibition space. For example, there is a text work discussing the process by which the current date line signs on Taveuni Island have come to be installed at their location, and a map of the Canary Islands showing El Hierro as the standard, before Greenwich was chosen as the prime meridian. The empty electronic signage on a wall also suggests the variability of maps that change depending on “who and for whom they are reproduced, and why and how they are reproduced, and what is depicted in them.”10 (Maps are unfixed things!) Also, eight vertical panoramic photographs arranged on the front and back sides of the four temporary walls that segment the space help viewers recognize that the date line is not a point, but a line. Tourists all gather around the place where the signs are located, but the actual date line is stretched throughout every place to the north and south of Fiji Island at the longitude of 180 degrees. The artist visited several places at the 180 degree longitude ranging from the southern coast of the island, through the forest, to the northern coast, recording these places in the format of a vertical panorama. This format suggests the 180 degree line of longitude which is a vertical line, but at the same time, it is another standard that deviates from the general format of a panorama (which is horizontal).

When installing the work shot in Fiji in Seoul, the artist included the specificity of the spacetime of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea within the work. The length of the original video, which was 48 hours long, was edited to an 8-hour and an 11-hour version to match the duration of the museum’s open hours.11 This way, the biological rhythm of the museum and the video’s rhythm are synchronized perfectly in real time. The beginning of the video is the opening of the museum and the end of the video is the closing of the museum, and there is no repetition, just like in life. The bearings of the museum are also reflected in the display. When looking at the installation from above, the temporary walls and the vertical panorama photographs are lined up in a row. The artist originally tried to match this line to the north-south direction of the museum. However, realistically it was not possible for the space to be composed exactly as the artist intended. Instead, the artist added a sign as part of the installation to inform the viewers of the actual compass position of the museum, as well as a drawing of the Southern Cross (which acts as a symbol of direction.) Although not intentional, this anecdote seems to paradoxically reveal the imperfections of maps. Maps are not perfect in nature, and the standards that determine the systems of our cognition are similarly arbitrary and random. The date line sign on Taveuni Island has moved to three different locations so far, and the church there exists in yesterday while the pastor’s house exists in today.12 There, our past is their future, and our future is their past.

Table 1.

Structure of the 4-channel video, The Island of the Day Before, The Island of the Day After

Translation: Doo Hee Chung

Proof-reading: Rave Hyo Jung Kim, Ana Tuazon