LEE Seulgi

Lee Seulgi continuously explores her interest in ordinary objects, everyday language, and natural forms through sculptures or installations with an emphasis on formal aesthetics. She especially enjoys collaborating with master artisans of folk crafts, such as Korean quilters in Tongyeong and traditional basket weavers in Mexico. She lives and works in Paris, and her works are housed in the National Art Center of Paris and the National Gallery of Victoria (Australia).

Interview

CV

Education

2000

DNSAP École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts de Paris, France School of the Art

1999

Institute of Chicago (Exchange student program), USA

Solo Exhibitions

2000

We Are Not Symmetrical, la Casa da Cerca art centre, Lisbon

2019

SOONER’S TWO DAYS BETTER, La Criée art centre, Rennes

Machruk, L’Appartement 22, Rabat

Depatture, Centre d’art La Chapelle Jeanne d’Arc, Thouars

2018

DAMASESE, Gallery Hyundai, Seoul

2017

DAMASESE, Galerie Jousse Entreprise, Paris

2016

Echo, Sindoh, Seoul

SOUP, Galerie HO, Marseille

2015

COPROLITHE!, Mimesis Art Museum, Paju

2009

IDEM, Centre d’art—La Ferme du Buisson, Noisiel

2008

AUTOMATIC: hommage au voleur, Galerie ColletPark, Paris

2004

Informal Economy, Ssamzie Space, Seoul

Selected Group Exhibitions

2020

The Moment of ᄀ [Giyeok], Seoul Arts Center, Seoul

Words at an Exhibition—an exhibition in ten chapters and five poems, Busan Biennale 2020, Busan

Born a Woman, Suwon Museum of Art, Suwon

Ruch-Hive, Manifesta 13, Marseilles

HYUNDAI 50, Gallery Hyundai, Seoul

Reality Is Not What It Seems, Galerie Jousse Entreprise, Paris

Home is a home is a home is a home, Galerie Jousse Entreprise, Paris

2019

Shinmulji, Wooran Foundation, Seoul

2018

(Extra)ordinary, KCDF Gallery, Seoul

AFFINITé(S), Galerie Jousse Entreprise, Paris

Navigator Art on Paper Prize, Chiado 8 Fidelidade, Lisbon

L, Château de Rentilly, Bussy-Saint-Martin

2017

The Other Face of the Moon, Asia Culture Center, Gwangju

Voir Une Poule Pondre Porte Chance, Palais de Tokyo, Paris

Zigzag Incisions, CRAC Alsace, Altkirch / SALTS, Birsfelden

2016

Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening, Gallery Hyundai, Seoul

Potential Visual Evocations, Florence Loewy, Paris

The House is Looking for an Admiral to Rent, National Museum of Contemporary Art, Bucharest

Monstrare, l’Ermite au blazer raisin, Centre d’art La Chapelle Jeanne d’Arc, Thouars Close Encounters, Le Praticable, Rennes

2015

Korea Now!, Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris

Séoul, Vite Vite!, Lille3000, Lille

N’a pris les dés, Galerie Air de Paris, Paris

LE MAUGE, Région des Pays de la Loire, Lycée public des

Mauges, Beaupréau

2014

Black Coffee, 25 rue du Moulin Joly, 75011, Paris

Burning Down the House, Gwangju Biennale 10, Gwangju

KUL LE ON HO BAK, Syndicat Potentiel, Strasbourg

Anti-Narcissus, CRAC Alsace, Altkirch

2013

Keep Your Feelings in Memory, National Resistance Museum, Esch-sur-Alzette

2012

We Gave a Party for the Gods and the Gods All Came, Galerie Arko, Nevers

Fiction Walk, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Gwacheon

La vie des formes, Les Abattoirs Musée d’Art Moderne et Contemporain, Toulouse ça & là, Fondation d’entreprise Ricard, Paris

La Triennale: Intense Proximity, Palais de Tokyo, Paris

2011

Les Innommables grotesques, Galerie L md, Paris

Basket Not Basket, Galerie Jousse Entreprise, Paris

La formule du binôme, Les Instants Chavirés, Montreuil

2010

Festival Plastique Danse Flore, Le Potager du Roi, Versailles

Sound Effects Seoul Festival, Sangsangmadang, Seoul

2009

Evento 2009: intime collectif, La Biennale, Bordeaux

Platform in Kimusa, Kimusa / Art Sonje Center, Seoul

2008

Annual Report, Gwangju Biennale 7, Gwangju

En marche, La galerie extérieure, Paris

B side, Gallery Hyundai, Seoul

2007

Elastic Taboos, Kunsthalle Wien, Vienna

We can’t be stopped, Galerie Nuke / Musée d’art contemporain du Val-de-Marne, Val-de-Marne

2006

A question(ing) of gesture, Leipzig Opera House, Leipzig

2005

Attention à la marche: histoires des gestes, La galerie / centre d’art, Noisy-Le Sec

Almost Something, Flux Factory, New York

2003

Propaganda, Espace Paul Ricard, Paris

May Your DV Be With You, Palais de Tokyo, Paris

2002

Korean Air France, Glassbox, Paris/Ssamzie space, Seoul

Anomalie italienne, Space Lima, Milan

Domino Party, Glassbox, Paris

2001

Traversées, National Museum of Modern Art, Paris 1997 FLIRT, Infozone, Paris

Selected Residencies

2009

Residency at Pilot program, Gyeonggi Creation Center, Ansan

2004

Residency at Ssamzie Space, Seoul

Selected Awards

2015

Sindoh Art Prize, Korea

Selected Projects

2019

IKEA Art Rug Project 2019, Stockholm

2017

Collaboration édition d’artiste, Hermès, Paris

2016

PETITE DENT, Manufactures des Gobelins du Mobilier National, Paris

2014

U, Aide de la Fondation Nationale des Arts Graphiques et Plastiques, Paris

2002

Le collège invisible, with Paul Devautour, ESADMM Beaux-Arts de Marseille, Marseille

2001

Le pavillon, workshop with Ange Leccia, Palais de Tokyo, Paris

Selected Collections

Mimesis Art Museum

Fondation Nationale des Arts Graphiques et Plastiques

FRAC IDF (Fonds Régional d’Art Contemporain île-de-france Le Plateau)

Lycée public des Mauges

National Gallery of Victoria

Critic 1

Talking through touch; listening through sight: The work of Lee Seulgi

Yang Okkum (Curator, MMCA)

Artist Lee Seulgi was born in Seoul. Since moving to Paris in the early 1990s, she has gone back and forth between Europe and Korea, producing mixed works that combine craft, sculpture, popular design and folk elements. An active artist whose work encompasses exhibitions, collaborations and public projects, she also established and ran alternative space Paris Project Room from 2001 to 2003.

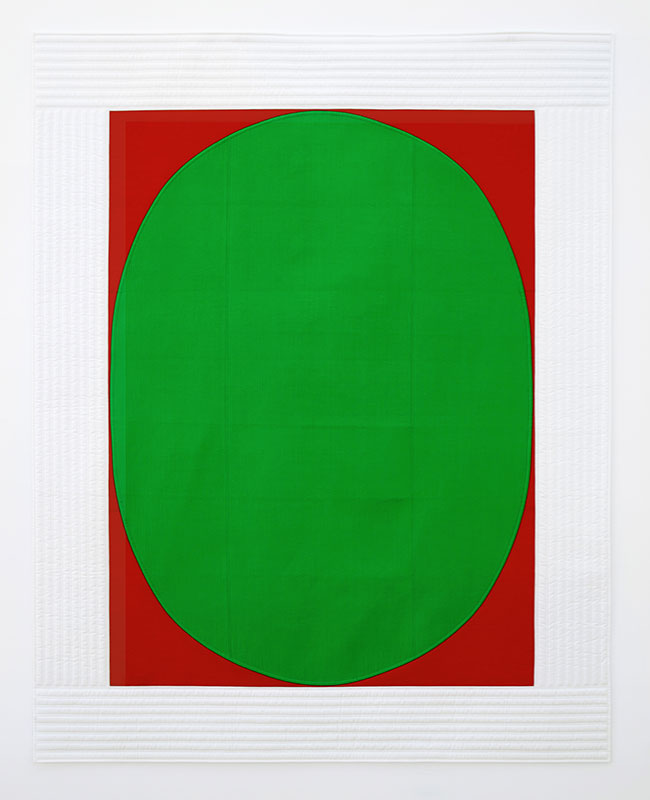

Blanket Project: U, the main work in Lee’s 2018 exhibition DAMASESE, at first appear to continue the lineage of geometric abstraction in view of their canvas compositions and visual symbols. But their titles—The Shoots Are Yellow, Spilt Water, Home Alone, My Own Fish to Fry—penetrate these powerful visual elements, providing a key for us to approach the works with greater lucidity. Built solidly on quilted blankets, the geometric-abstract faces and patterns combine with the proverbs in the titles of the works, neatly and lucidly revealing the narratives and implications of proverbs imbued with the group consciousness of a community. In one text, Lee and Arlène Berceliot Courtin write, “a proverb is a single metaphor built through a situation or picture. People believe proverbs, yet don’t believe them. Proverbs move our subconscious. Doesn’t a community become possible when we start recognizing certain forms and symbols together? Regardless of where we are born.” These implications contained in tales and proverbs that pass through accumulated layers of time, remaining alive and refusing to evaporate, are visualized by handcraft techniques through Lee’s collaboration with master quilters in Tongyeong. Lee calls quilts, “places on the boundary between dreams and reality, and shamanistic sculptures that influence dreams.” As items used in the act of sleep, which links the subconscious and conscious, Lee’s quilts combine the visual language of contemporary aesthetics with the tactility of crafts, condensing the narratives of proverbs that form a concise and humorous system.

In addition to her work with master quilters, Lee Seulgi has engaged in various collaborations of a different nature. Here, her attempts to sustain disappearing languages and cultures by borrowing matter and materials from the past have been expanded into her work. In Basket Project W, she worked with craftspeople in Santa María Ixcatlán, a small village in the north of Mexico’s Oaxaca state. The disappearing magic culture and language of a Mexican minority community are made into sculptures and videos featuring the community’s symbolic baskets, and the people and processes that make them. These works are meant to call into the present the language and culture that once existed but are now dying out, and to build a bridge to their primitive forms. This serves to recall the memories and existence of things forgotten in our era as it races on toward somewhere in the future, attempting to postpone their disappearance and, thereby, evoking our current lives.

Lee Seulgi’s works, beginning with explorations of daily life and objects, demolish fixed ideas about them and enable new views. They use single objects to link past and present, showing tactile weavings that built narratives mixing fine art and craft, the abstract and the figurative, tradition and contemporaneity, literature and art, the linguistic and the visual. Here, weaving is an important technique and device in Lee’s work that includes the “tying together” that she speaks of, the relocating moves and images that characterize weaving, and the narrative features that unfold in the rhythm of predicting the next move. The products of Lee’s working methods and attitudes, flexibly influenced by the mixing and changing of different genres, leads me to believe that Korea Artist Prize would allow her to further increase the range of her work in the future; I think now is a more appropriate time than ever for this to happen.

Critic 2

The Aesthetics of Weaving: Lee Seulgi and Sculptural Practice

Kim Sungwon (Curator/Critic, Professor at Seoul National University of Science and Technology)

One of Lee Seulgi’s featured installations in this exhibition is entitled DONG DONG DARI GORI, a portmanteau term that combines a famous Goryeo folk song named “동동” (i.e., “Dong Dong,” sometimes called “Dong Dong Dari”) and “달걸이” (i.e., “dalgeori ”), which is a type of folk song with thirteen verses, consisting of a preface and twelve verses describing the singer’s wishes for each month. The “Dong Dong” song, which is thought to have originated from the sound of a drum beat, takes the dalgeori format and was often sung by Goryeo woman longing for their beloved in each month. Also, the Korean word “달걸이” contains “달” (moon) and “걸이” (to hang), which inspired Lee Seulgi to think about a motion or device for hanging the moon. Furthermore, “걸이” is a homonym with “거리” (streets), thus evoking the streets where people walk and interact. While these linguistic associations might seem trivial to some, Lee Seulgi’s relationship with language goes much deeper than mere wordplay. As a Korean who has lived in France for more than thirty years, both of her primary languages— Korean and French—can at times be familiar and unfamiliar to her. This intermediary status helps Lee to formulate a new grammar that reveals unfamiliarity in the familiar, and familiarity in the unfamiliar.

Like its title, DONG DONG DARI GORI transcends familiarity by infusing everyday things—such as doors, water, songs, and games—with new vibrancy. However, it is not easy to explain or understand the works expressed by Lee’s linguistic associations. In The Craftsman, Richard Sennett outlined the difficulty of delineating the relationship between thinking and working with one’s hands. Using the model of cooks explaining their recipes, Sennett emphasized the power of empathetic examples, scene narratives, and metaphors for triggering the imagination. He further suggested that this method applied not only to the culinary world, but also to almost any conceivable field, from computer and music instruction to philosophy.1 While it might be overly simplistic to correlate a chef’s explanation of a dish with an artist creating works, metaphor—which flows forward and spreads sideways, forming new meanings—certainly plays an essential role in understanding Lee Seulgi’s art.2 Through metaphor, Lee’s creative language and ideas avoid the trap of familiarity to be reborn as living forms that stimulate the imagination and deepen the meaning of her exhibitions. Hence, metaphor is the driving force of Lee Seulgi’s works.

Exhibition Expressed Through Metaphor

Rather than conveying some semantic meaning about the exhibition, the title DONG DONG DARI GORI simply provides a certain sound, rhythm, and movement, like an incantation or the fanfare opening an event. The core elements of DONG DONG DARI GORI—door, water, play, song—are similarly neutral, impartial, and even abstract. Some of the motifs invoke Korean traditional culture, such as the patterns of wooden frames, designs representing dancheong (decorative coloring on wooden buildings and artifacts), and songs of the darisaegi (leg counting) game. But here, those elements are combined with toys from seventeenth-century France and water from various rivers, sent to Lee Seulgi by her friends around the world. Together, all of these components encourage us to explore the relationship between oral tradition, handicrafts, folk entertainment, and contemporary art. Moving and operating within the same space and time, these diverse and antiquated components prompt new ideas about the relationship between traditional culture and contemporary art, as well as about dualities such as materials and culture, artifacts and organisms. Lee’s use of the folk song “Dong Dong Dari ” derives from her research on oral tradition, which she has conducted over the last several years. During this time, she has studied the French tradition of chanson légère (literally “light song,” referring to sexually suggestive folk songs), and also collaborated with contemporary trainees of intangible cultural heritage. The artist originally looked for such light, suggestive traditional folk songs from Korea, but was unable to find what she was looking for. Thus, her preliminary design for this exhibition focused on the traditional “Beggar’s Song,” which combines such content with references to the moon. To evince the public square of the past, where the sound of drums would resonate, she connected a large drum resembling the “rabbit in the moon,” which she had previously made, with a sinmungo, a type of drum that was once sounded by Joseon civilians to report injustice to the king. Hence, the “거리” (streets) in DONG DONG DARI GORI symbolizes the square, where various narratives are created and exchanged among people, while songs of labor or revolution resound. But upon entering this square, we notice that it is almost empty, with only a few odds and ends randomly placed here and there. Lee Seulgi claimed that she wanted to “undress the space,” or strip it.3 Was she perhaps motivated by her research into lewd folk songs? In any case, despite being “undressed,” the square never feels squalid or desolate. Indeed, the intentional sparseness and restraint allows exotic new narratives to emerge. In our current era of information overload and material abundance, Lee’s square reminds us that deprivation and loss can be effective catalysts for the imagination.

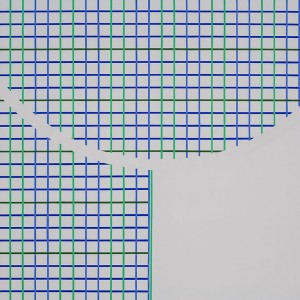

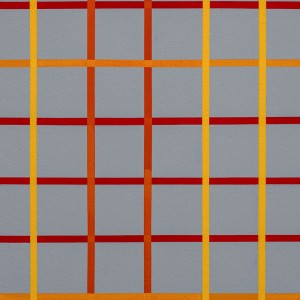

The square does not contain any of the brilliant colors or striking shapes that we have come to expect from Lee Seulgi. The various works—including glass bottles, geometric wall drawings, and structures made from achromatic cement and wood—cannot be easily perceived, while the songs are barely audible. Wall drawings representing the Northeast Gate, Northwest Gate, Southwest Gate, and Southeast Gate open wide in four directions. But the exit and entrance to the space are somewhat vague, since these “gates” do not resemble ordinary doors. Instead, they are “moon doors,” featuring geometric wooden frames with designs representing the rotation of the moon. Visitors are encouraged to imagine how the semicircles (i.e., partial moons) can overlap and rotate into a full moon. Thus, a set of minimalist geometric wall drawings come together to create the “moon door,” illuminating the square while also recalling the shape of a woman in late pregnancy. The “moon doors” are the only works in the square that are colored, having been painted by dancheong artisans with special pigments containing shellfish powder. Notably, however, one of the colors is purple, which is never used in traditional dancheong. This heterogeneous intervention implies the coexistence of the artificial and the natural. Standing in the center of the square is a wooden frame structure entitled 13332244 (2020) which is slightly concealed by a pillar. The arrangement of grids on this structure mirrors that of the “moon door” drawing on the wall. Although the structure still recalls the “井” shape of classic wooden frames, the geometric form has been reinterpreted outside the context of tradition. According to the artist, the structure of this door and frame are meant to reflect the moon and the surrounding melody. The combination of the rigid wooden frames and the soft love songs sung by women (such as “Dong Dong”) form a compelling metaphor for the relationship between men and women, or yin and yang. Using another level of wordplay between the homophones “문” (“mun,” the Korean word for “door”) and “moon,” Lee links the circular revolution of the moon and the geometric structure of the Korean wooden doors. In a recent interview, she said that “removing the outer part of the frame of the door would leave just the inner tines, which are like bones, as the primary content.”4 Eliciting movement and flexibility, the “moon door” to this exotic square opens and closes. In the process, the inside becomes the outside and the outside becomes the inside; the familiar becomes unfamiliar and the unfamiliar becomes familiar.

The space also contains a long, low gray structure in the shape of an “L,” where three unusual wooden devices can be found. Respectively entitled BAGATELLE 1, BAGATELLE 2, and BAGATELLE 3, these devices are derivations of the French game Bagatelle, a pre- cursor to billiards, pinball, and pachinko that was popular in the seventeenth century, during the reign of Louis XIV. Using a stick, the player tries to maneuver a ball into a small hole, avoiding nails or pegs that are pounded into the board. Significantly, the French word “bagatelle” means something that is useless or trivial, but it can also be a slang term for sex. The bagatelle games are reborn as unique and sensual “sculpture-game devices,” wearing the body of a prehistoric goddess discovered by archaeologist Marija Gimbutas.5 Walking past BAGATELLE, visitors hear a song coming from somewhere, but the sound is mumbled like someone talking under their breath, much too weak for a song in the public square. This sound work is taken from the aforementioned “leg counting” game. However, whereas the original tune is used by people to count, Lee’s version replaces the numbers with random words. But even with its meaningless lyrics connecting mundane and crude words, the song is oddly addictive, with a pleasant harmony. A set of five songs are played in the space at 5, 10, 15, 30, and 45 minutes after the hour. In the square of DONG DONG DARI GORI, the revised versions of BAGATELLE and the “leg counting” game exist as simple monuments to oral tradition and folk entertainment, illuminating the neglected history of leisure, unproductive labor, and secular folk values.

Hanging on one wall of the exhibition are several small but elaborate glass bottles with various shapes. From a distance, only traces of light reflected from these bottles can be seen, neatly evincing the presence of inconspicuous beings. A closer look reveals that the containers actually hold small amounts of water from rivers in Europe, the US, and other distant places. The artist asked her friends around the world to collect this water from any nearby rivers that flow to the the sea, which thus represent a natural network connecting the planet. In a world that has been brought to a halt by COVID-19, this act represents people’s dim hopes to regain mobility, freedom, and exchange. Amazingly, this hope was realized when Lee’s friends were able to come to Seoul to see the exhibition despite the pandemic, if only in the form of river water in glass bottles. Collectively, the glass bottles are entitled Différence entre Fleuve et Rivière, but each bottle is also labeled with the name of the river that the water came from and the name of the friend who collected it. In addition, each glass bottle is roughly shaped like its respective river.

Weaving baskets

In previous projects (e.g., Blanket Project U, Tamis Project O, and Basket Project W ), Lee Seulgi has explored local identity, folk culture, and tradition by observing artisans and handicrafts and converting her observations into aesthetic language. Collaborating with local artisans, Lee created abstract geometric structures based on colorful quilts, round tamis sculptures from an old beech tree, and basket sculptures woven from palm leaves. In Basket Project W, for example, Lee worked with the people of Oaxaca, Mexico, who rely on basket weaving to support their entire village. For these villagers, who begin learning to make baskets from the age of three, basket weaving is an essential form of work and play. In fact, the transmission of basket weaving through actual practice is the driving force that sustains the village. However, the practice of basket weaving is inextricably tied to the villagers’ native language of Ixcatec, which is now going extinct due to the spread of Spanish as the predominant language of Mexico. For this work, Lee Seulgi placed various baskets made by the villagers on tall geometric pedestals resembling flamingo legs, produced by French metalsmiths, resulting in forms that looked like people or animals. Each work was accompanied by a title in the Ixcatec language. Hence, “W” from Basket Project W is like an imaginary place where Georges Perec’s W ou le souvenir d’enfance (1975) meets the basket weaving and Ixcatec language of the Oaxaca natives. Reconstructing (language) extinction, disconnection, wounds, and the memory of a community, Basket Project W raised questions about how contemporary art can engage with oral tradition and folk handicrafts to forge new paths and possibilities. Indeed, such questions continuously appear from the works of Lee Seulgi, to the point that they form the foundation of her art.

Wearing the attire of metaphor, Basket Project W, Blanket Project U, and Tamis Project O sport brilliant colors and unique shapes, but they do not remain objects for mere contemplation. Furthermore, the baskets, blankets, and tamises that were elaborately produced with expert craftsmanship are not intended to shed new light on traditional crafts. Rather than simply trying to convert traditional handicrafts into contemporary art forms, Lee Seulgi seeks to achieve a deeper, more meaningful connection between the past and present, which promises greater rewards.

Her mode of production exemplifies the ideas of British anthropologist Tim Ingold, who wrote about the narrative characteristics of weaving, wherein all movements have a linear history, developing rhythmically from previous movements while predicting the next movement.6 While offering new prospects for the relationship between language and handicrafts, Ingold’s conception also integrates history, artifacts, organisms, nature, and culture, and the entire world formed by the interactions of these elements. Using the example of basket weaving, Ingold challenges the notion that artifacts are produced while living organisms grow. Although baskets are obviously not living organisms, they are made with a process that completely differs from the production of other artifacts, and this process shares many similarities with the growth of living organisms. In basket weaving, as Ingold explains, the artisan interacts with the materials without changing their properties, constructing a unique surface with no distinction between the inside and outside. By erasing the divide between humans and non-humans, Ingold revises our conception of nature and culture. For Ingold, the process of production is based on an action’s capacity to produce a given object, whereas weaving focuses on the essence of the process by which the object is produced. Thus, in production, the object is regarded as an expression of thought, but in weaving, the object embodies rhythmic movement. With this in mind, Ingold recommends replacing production with weaving, and replacing thought with movement.7

Ingold’s concepts nicely illuminate Lee Seulgi’s artistic practices. Using handicrafts and oral tradition as her materials, she proposes new prospects for tradition, community, regional identity, folklore, and locality. In Ingold’s sense, her efforts to use art to reestablish relations with the world is closer to weaving than producing. While all of her projects spark contemplation, they also manifest function, while the various elements evolve and create new forms, like living organisms. Like the works from her previous handicraft collaborations, her Bagatelle games are also sculptural objects that presuppose functionality. Beyond their obvious or immediate use, her sculptural crafts function by connecting us to the world, enabling movement, and weaving history with the present. Originating from her observations of sustainable technologies, her works involving baskets, tamises, and blankets address vanishing languages, memories, and communities, and are thus never finished or completed. With such functionality, Lee’s sculptures remain open and alive as part of an ongoing process for something that is yet to come.

From Basket Project W to Blanket Project U, Tamis Project O, and Island of Women and DONG DONG DARI GORI, Lee Seulgi’s artistic practices cannot be reduced to simple expressions of fixed concepts. Each sculpture of a basket, tamis, or quilt represents a type of movement, weaving the traditional and contemporary, sculpture and handicraft, oral tradition and text, individuals and community, private and public sphere, the local and global. In Basket Project W, she used Georges Perec’s W ou le souvenir d’enfance to revive the disappearing Ixcatec language, while in Island of Women, she used oral tradition to revive dead symbols and places. In Blanket Project U, she connected geometric figures, quilts, and folk proverbs in blanket sculptures that dream, speak, and imagine. In Tamis Project O, she used round tamis with unusual shapes as triggers for wordplay. Finally, in DONG DONG DARI GORI, she invites us into the square where doors, water, songs, and games mix, move, and become metaphors. Rather than objects for quiet contemplation, the assorted works of this exhibition arouse the complexities of our lives, experiences, and environment, encouraging us to weave the world ourselves.

1 Richard Sennett, The Craftsman, trans. Kim Hongsik (Seoul: 21th Century Books, 2010), 298–308. Ibid., 309.

2 Ibid., 309.

3 From my interview with Lee Seulgi on October 14, 2020.

4 Ibid. In Korean, the inner tines of the frames are called “살,” which also means “flesh.”

5 Lee Seulgi said that she was inspired by an image of a prehistoric goddess in Marija Gimbutas’ The Language of the Goddess: Unearthing the Hidden Symbols of Western 5 Civilization (San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1989). From my interview with Lee Seulgi on October 14, 2020.

6 Tim Ingold, Marcher avec les dragons (Bruxelles: Zones Sensibles, 2013), 217.

7 Ibid., 216.

Critic 3

In Search of the Rabbit in the Moon

Elfi Turpin (Art director, CRAC Alsace)

The writing of this text began in June 2020 when Lee Seulgi asked me to send her water from two rivers that I walk along every day. The first is the Ill. It flows through Altkirch, a French community that is home to the CRAC (Rhenish Contemporary Art Center) Alsace, the art institution that I direct. The second is the Rhine. This long river passes through Basel, a neighboring Swiss city, and provides the “R” (Rhenish) in CRAC. The Ill is an extensive waterway that spans the Alsatian plain from south to north. It feeds the Rhine, which delineates the border between Germany and France before it flows onwards to the North Sea. Once collected and mailed to Lee Seulgi, the waters of these rivers were encapsulated in small glass containers with shapes reminiscent of the portion of their flow where they were collected. They were then mounted as pendants on long chains to be hung on a wall alongside other waters collected from rivers and seas in the neighborhoods of dozens of curators with whom Lee Seulgi has worked in different areas of the world. While the pandemic confines our bodies inside distance, lack of contact, quarantine, and isolation, Lee Seulgi succeeded through this operation in arranging an artistic community to accompany her physically, if not metaphorically, through the process of research and production of an exhibition in Seoul and then in convening within the exhibition space the absent bodies of these interlocuters. The composition of these aquatic samples surely speaks volumes about the living environments of their senders, about the minerals, bacteria, other microorganisms, and the more or less toxic particles in which they bathe, as well as about the emotional, political, and artistic territories in which they act.

Looking back at the two photos ⦾ 1, 2 that I took to document the location of the collection of these samples, I think particularly about several works shown by Lee Seulgi at the CRAC Alsace when she participated in two group exhibitions. The first presents a sculpture of an eel that serves also as a tool for fishing for one.⦾ 3 It is a long branch that she collected, probably at the riverside. She peeled away its bark, polished it, incised it with a penknife, and then fully colored it with graphite to give it the shine of fish skin. A trident completes the head of the beast. Set at the entrance of the art center, this manipulable sculpture introduced the main issues of the exhibitiion, entitled Anti-Narcisse,1 which attempted to redistribute the relations between the viewers, work, and artist and between subject and object. It was an exhibition where we no longer viewed works as objects in which we tried to recognize ourselves, but as forms of thoughts produced by the artists whose multiple points of view we attempted to endorse; an exhibition where the artists themselves no longer produced objects but motive forms for which they borrowed devices and conceptual regimes from the environments in which the works took shape and came to speak, as if others had conceived them; an exhibition where people practiced an exchange of perspectives and the absorption of other points of view. Eel (L’ANGUILLE, 2012) by Lee Seulgi—a harpoon in the shape of a silver eel, an object taking on the appearance of the animal it is designed to harpoon— activated this practice of the exhibition by engaging the viewer to observe a thing from the point of view of the thing being observed, to shift perspectives and make art a matter of subjectivity in transformation. Lee Seulgi’s manipulable works are thus much more than performative, transferring viewers’ points of view into that of a motive object of a thought. In another room in the exhibition, Lee Seulgi presented her Nubi blankets,2 traditional blankets with geometric color patterns that she has been making since 2014 in collaboration with exceptional artisans in Tongyeong, South Korea. The colorful geometric compositions that she designs are visual transpositions of Korean colloquialisms brimming with imagery, such as “eating a rice cake lying down” (meaning doing something with great ease, like ‘piece of cake’), “licking the watermelon” (botching work)⦾ 4, or “showing duck feet” (feigning innocence). The blankets under which we sleep and dream speak to us. In this sense, these works that envelop, warm, and protect our bodies are active. They tip us into the reality of our dreams. One day, the colors left the blankets, giving way to blacks and whites, ghosts, and ominous sayings. To a series of nightmares.⦾ 5

The second image,⦾ 2 taken on the bank of the Rhine at the end of a day in June 2020, shows the first purple light of twilight and sends me back to an experience with Lee Seulgi at another group exhibition at the CRAC Alsace entitled Zigzag Incisions where she delved even further into a process of transformation regarding the relation to the work.3 On the walls of a room painted in the mauve of twilight in Altkirch,⦾ 6 Lee Seulgi offered the public a soup of the same color made by cooking local seasonal vegetables, mainly purple and violet carrots and mushrooms. It was served in bowls crafted by a ceramist in the city. According to Lee, if the color of what we ingest is the color of what we see, and if the inside becomes equal to the outside, then we can become invisible, or more like we can experience the disappearance and dissolution of the subject in its environment. Perceiving the color consisted in absorbing it in order to adopt its point of view: to become color.

This long introduction now brings me to the doors of the exhibition DONG DONG DARI GORI, at least to how I imagine it today. This is because the four doors that articulate this project have also undergone a slow metamorphosis. Initially planned to be built in wood using a complex assembly and weaving of long painted slats, these monumental doors designed to the scale of the space have gradually dematerialized to leave room only for the traditional decorative colors meant to protect their wood. Thus, the four grand sculptures were transformed into large wall paintings signifying the frames of open doors. The geometric weave of the wood has given way to a tangle of colored lines: a pictorial interlacing created in collaboration with painters expert in Korean color and the painting adorning the exterior of traditional buildings or Buddhist temples.⦾ 7 The object having disappeared, the painting lost its decorative function and became pure agentivity (agency). The pigments remain active and powerful. The doors are made up of four tones or shades corresponding to four orientations in space. There is a door that goes from a flesh color to dark brown (close to the color of the “red bean soup” that Koreans eat to ward off evil spirits), a door that goes from yellow to red, a door that goes from mauve to dark purple, and a door that goes from blue to green.

These four doors are respectively made up of two frames, and each has a semi-circular cutout, a sort of a half-moon or section of the moon that evokes the image of a star seen at night through the openwork shutters of a room within a house. If Lee Seulgi’s blankets tip our bodies into sleep and dreams, these painted doors oddly tip our bodies into the metaphorical space of a room, the intimacy of a night in search of, as the artist tells us, “the rabbit in the moon.” The intimacy of bodies, and in particular of women’s bodies, seems to be mobilized through this device, however immaterial it may be. It all goes back, in fact, to their delayed presence. The voices of old women recorded in the 1990s singing a song for a “counting legs” give a rhythm to the space and punctuate the visit. This song that accompanied a children’s game of entangling each other’s legs “in scissors” is repeated here in a loop of five voices, becoming an incantation.

Wooden sculptures are placed on a bench, taking on the form and system of an indoor table game practiced in Europe known as Bagatelle, a sort of analog pinball machine derived from billiards, an ancestor of pinball and Japanese pachinko. This game consists of a slightly inclined board on which a course consisting of holes and pins is set. It is played with balls and a cue. It is interesting to note that the word “bagatelle” in French spans di erent meanings. It can designate something unimportant and trivial, something inexpensive, or even carnal love, sex, or a short, simple, and light musical composition. Many expressions, now mainly fallen into disuse, feature the word ‘bagatelle’ and have a strong sexual connotation, such as “to love the bagatelle,” “to think only of the bagatelle,” or “to be no longer concerned by the bagatelle.” The manipulable version of the Bagatelle game made by Lee Seulgi synthesizes the uses of the object with its various meanings: The composition of the holes and nails recalls or hides a woman’s body, an entire body, or her sex, reducing the sexual act to ritualization through play. From this perspective, all the forms and objects invoked by Lee Seulgi in this exhibition take on a strong sexual intentionality. When worn, the long chains with their pendants containing rivers and seas reach between the legs, just like the footwork sung by women happens between the legs. In colloquial French, “the moon” means “the ass,” which one watches closely here with Lee Seulgi through the door in search of the rabbit in the moon, that is to say in search of a hidden motif that carries a popular story. If in this search the artist observes and experiments with vernacular practices, for example through collaboration with artisans, it is because she tracks the alternative or subordinate forms of epistemology that these forms condense. She traces the power of transformation of cryptic popular practices, their ability to resist and to act in the world.

⦾1

The Ill, Altkirch, June 19, 2020

⦾2

The Rhine, Basel, June 19, 2020.

⦾3

L’ANGUILLE, 2012. Photo: Paolo Codeluppi.

Seulgi Lee © ADAGP Paris.

⦾4

U: Lick the Watermelon. =Rush job., Coll.

The NGV Mel- bourne, 2014.

Seulgi Lee © ADAGP Paris.

⦾5

U: To cut water with a knife. =A quarrel between a couple never lasts.,

CRAC Alsace, photo: Aurélien Mole, 2017.

Seulgi Lee © ADAGP Paris.

⦾6

SOUPE, CRAC Alsace,

Photo: Aurélien Mole. 2017.

Seulgi Lee © ADAGP Paris.

⦾ 7

Jibokjae in Gyeongbokgung Palace, Seoul.