Koo Donghee

Interview

CV

2013

Extra Stimuli, PKM gallery, Seoul, Korea

2012

Donghee Koo, Doosan Gallery, Seoul, Korea

No dog walking on the roof, Doosan Gallery, New York, U.S.A.

2008

Synthetic Experience, Atelier Hermes, Seoul, Korea

2006

Disturbance, Arario Gallery Seoul, Seoul, Korea

2005

The Day Off Duty Free, Akademie Schloss Solitude, Sttutgart, Germany

<Selected Group Exhibitions>

2014

Korea Artist Prize 2014, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Gwacheon, Korea

How to Hold Your Breath, Doosan Gallery, Seoul, Korea

2013

Animism, Ilmin Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

Expanded Cabinets of Curiosities, Arko Museum, Seoul, Korea

DEEP FEELINGS. From antiquity to now, Kunsthalle Krems, Krems an der Donau, Austria

2012

I spell on you, The 7th Media City Seoul 2012, Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

The 13th Hermes Art Award, Atelier Hermes, Seoul, Korea

The Body as Sculpture III, Musee Rodin, Paris, France

Road to 12,104 miles, Placio Nacional de Las Artes, de Glace, Buenos Aires, Argentina

The Itinerary of Mobility and Translation, Korean Cultural Service New York, New York, U.S.A.

Santarcangelo.12 Festival, Museo Storico Archeologico di Santarcangelo, Rimini, Italy

How Physical, Yebisu International Festival for Art & Alternative Visions, Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, Tokyo, Japan

2011

Vidéo et aprés, Ondes et flux, Centre Pompidou, Paris, France

Space Study, Plateau, Seoul, Korea

19min Performance Relay, Alternative Space Loop, Seoul, Korea

From blank pages, Art Space Pool, Seoul, Korea

2010

Courage, Contemporary Art from Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, Centro Saint-Bunin, Aosta, Italy

Platform Seoul 2010 Projected Image, Art Sonje Center, Seoul, Korea

2009

Video: Vide&0, Arko Museum, Seoul, Korea

Magnetic Power, Coreana Museum of Art, Space C, Seoul, Korea

100 Daehangro, Arko Museum, Seoul, Korea

2008

Now Jump!, Nam Jun Paik Art Center, Yongin-si, Gyeonggi-do, Korea

Donghee Koo, Hyunjhin Baik, Dongwook Lee, Arario Beijing, Beijing, China

On the Road, The 7th Gwangju Biennale, Annual Report; Gwangju, Korea

2007

Disturbed, Peres Project, Berlin, Germany

Le Truc, Project Arts Centre, Dublin, Ireland

Close Studio, Open Café, Tokyo Wonder Site, Tokyo, Japan

AllLookSame? Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, Torino, Italy

2006

Beautiful Cynicism, Arario Beijing, Beijing, China

2005 Video Screening, Ssamzie Space, Baram, Seoul, Korea

2004

Interference, Römer Str. 2, Stuttgart, Germany

Video Screening, Platform Garanti Contemporary Art Center, Istanbul, Turkey

<Awards>

2012

The 13th Hermes Foundation Art Award, Seoul, Korea

2010

The 1st Doosan Yonkang Art Award, Seoul, Korea

2000

Susan H. Whedon Award, Yale University, Connecticut, U.S.A

Critic

A Way of Replay by Koo Donghee: Amusement and Vertigo

Chung Yeonshim

(Critic and Associate Prof., Hongik Univ.)

I. A Way of Replay, August 2014

An intense yellow track is presented before you. This atypical installation that commences at the entrance of the exhibition space resembles a cave with narrow entrance. This structure, composed of stairs, appears as if it is taking off and soaring. As you follow the path with your body slightly slouched, you run into several projection screens installed by the areas around the curve. I have never been this high up inside the museum. Heading toward the ceiling, my body tenses up like never before in an effort to keep my balance as well as my sense of coordination. The further I go, the more I realize that the trail in no way serves as a guide for the path to come. The moment I notice this, going back does not seem like an option.

Seeing that continuing forward is much easier than taking steps backwards, I arrive at the halfway point. A permanent wall has been erected at the center. Spanning the width of that wall, each step of the trick stairway that forms this structure conforms to create an illusion of a discontinued path; thus, these are stairs in form only. Glancing at the surroundings, I picture the amusement park rides that I used to enjoy as a child and keep a keen eye on the flowing line of movement. This is not the conventional gallery scene. It feels as if the ceiling is suspended above my head. It becomes difficult to keep your back straight and you naturally begin to slouch. The scene of the space changes according to the standpoint of the audience. As both a participant and an observer, the viewer is able to reconfirm the space and objects through what is called parallax viewpoints.

No one observes the exhibition in exact same way. Not before long, you encounter the second projection screen. My body instinctively swerves the instant I turn the curve, and there it is, the second screen. It is a video of people on the rides at Seoul Land, and it is unclear whether the accompanying jumbled noises are screams or sounds of joy. I continue walking a bit further and arrive at the third screen; this is the final peak – the climax – of the track. If too tired, viewers have the option to stop here and get off the track via the stairs attached on the side to either end this journey or to simply take a break. Otherwise, viewers can carry on toward the last spot. The minute you reach the last location, you face the last screen, as if you have come across a cul-de-sac. Each viewer begins this exploration with a camera secured on his or her head, and the video on the screen displays the path – the journey – that each individual has just taken. I complete this journey by jumping off the track.

Upon entering the exhibition space, you immediately become a constituent of the space and, thus, directly participating in the exhibit is inevitable. I met with Koo in advance to gain a conceptual understanding of her work, and I visited the museum again a week prior to the opening of the exhibition in order to see firsthand how the structure is actually assembled1. Although Koo worked in collaboration with architect Seohong Min in designing safety measures, method of construction, and three-dimensional mapping systems, the inherent concepts of “replay” are a part of Koo’s own idiomatic expressions and are extensions of her previous works. (In the following pages, I examine the associations as well as the idiomatic expressions of contemporary art that Koo incorporates in her works).

Situated inside the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, Koo’s installation bears resemblance to the Möbius strip; indeed, the inner and outer sides of the structure are quite ambiguous. Albeit not like the glass pavilion works by contemporary artists like Dan Graham, Koo’s structure appears to be composed of numerous yellow tape belt-like formations that enable viewers to observe the space simultaneously from both the inside and outside. While this pseudo-architecture or pseudo-structure may appear to be a provisional edifice with indistinct boundaries, it has actually been constructed to ensure sturdiness and safety; and (although not intended by the artist) children are required to be accompanied by an adult for safety reasons.

If this structure is in fact modeled after the Klein bottle and the Möbius strip, it should lack an structural endpoint. This is related to the mathematical logic behind the Klein Bottle; just as the interior and the exterior of the bottle is undecipherable, we cannot be entirely sure about whether we are walking on the inner or outer sides of the track. With such structural concepts in mind, Koo’s Way of Replay presents projection screens as a form of media that connects such notions with reality. Hence, the screen at the final point of the track symbolizes a recreation of images that connect the gallery space with these notions as well as a collage of images that represents our memories (or, perhaps, our traumas). The images on the screen function as a sort of “reenactment code” that are reminiscent of the route that I have taken.

My recollections about the Klein Bottle are from Se-hui Cho’s novel, The Dwarf. To the generation of people who read this novel, the Klein Bottle or the Möbius strip are conditional expressions as well as symbols that reflected the reality and the adversities of the time; and to the people who weaved their everyday lives along that ambiguous path, those terms were metaphors that carried paradoxical meanings of despair and hope. Relating the Klein bottle to the circumstances of the time period, the narrator of the novel states, “In this bottle, inside becomes outside and outside becomes inside. Because there’s no inside or outside, we can’t talk of containing the inside – the notion of closing has no meaning here. If you just follow the wall, you can get out. So in this world the notion of enclosure itself is an illusion.”2 Way of Replay is more than just an installation. While influenced by the Klein Bottle, Koo’s work goes further and makes the constituents of the space the axis of life stories.

Accordingly, the title Way of Replay for Koo’s pseudo-architecture/pseudo-structure carries various meanings. The term “replay” signifies not only the idea of playing something again but also images that inform us of and confirm our past. As a verb, “replay” means to playback recordable media (e.g., cassette tapes, videos, films) or to repeat a series of incidents. As a noun, it refers to a meticulous examination of recorded audio or video via playback or to a pattern of recurring past incidents or appearances. By combining the words “replay” and “way,” Koo arouses our sense of daily routine and recollections and, also, links the various points in which our past journeys turn into images and return to our minds in the form of memories. These points take on the role of stimulating forgotten memories.

Precedents of alluring, maze-like works similar to Way of Replay do exist. An example is Koo’s Look Who’s Talking – a mixed media installation from 2009 – that was installed in the Arko Art Gallery for its 30th anniversary ceremony. Following the route created by an undulating space, you arrive at an area where the visual works that you had seen earlier are nowhere to be seen. Surely, the audience can tell by looking at the installation that the path inside resembles a labyrinth; however, even after passing by a monitor, a large mirror, a bird’s nest, among other objects, the audience is not able to precisely discern what is going on inside the gallery. The works that we experience and observe inside the gallery provoke our sense of visuality; in contrast, deep inside the gallery, we find a parrot. Once the exhibition begins and for the duration of it, the gallery’s docents and staff members teach words and phrases to the parrot, and the bird learns by repetition. A gallery space is normally a room that artists oversee and in which they install their works. However, in Koo’s case, it is a space of “uncontrollable coexistence,” and we are persuaded to contemplate the interaction between a gallery and a zoo. When designing the Panopticon, which enabled watchmen to observe all inmates from a single point, Jeremy Bentham regarded the royal menagerie garden at Versailles as the ideal archetype to model his design after. By the same token, many artists considered that zoos are a perfect example of an ocularcentric spatial design that both controls the works’ subjects and divides spaces. Koo seems to be suggesting that we reconsider the visual element of seeing, the limitations of visuality, and the rational and practical notion of “seeing is believing” against gallery conventions. The sounds of the parrot imitating words symbolize a new rule that breaks the old museum convention that places much focus on objects. Likewise, our vision and auditory senses interact within a neutral space. In this 2009 installation, Koo experiments with a maze-like structure as well as monitors that connect the structure’s corners.

Instead of drawing attention to a coherent artistic style, Koo seems to focus on dissecting sporadic concepts and has shown much interest in the ideas and coincidental correlations that arise as a result. She does not work toward a goal with distinct aesthetic ideas and effects in mind. She is comparable to a writer who, instead of providing consistent stories, focuses more on imagery and powerful diction that connect scattered words. However, this project is slightly different from her previous works. Compared to most of her earlier works that came across as intellectual and conceptual, her current work enables a person to become immersed into the installation. Her Kinkaku-ji model installation at the Atelier Hermes, Blind Spot – a multisensory work – shown at Space Study, Plateau, and the works displayed recently at Doosan Gallery all fulfill theoretical desires and come across as both conceptual and somewhat vague.

Nevertheless, the yellow Way of Replay is reminiscent of our organized memories that feel very familiar yet foreign to us. Once you hear the title – Way of Replay – that emphasizes repetition of structure or, perhaps, patterns, we begin to wonder about a repetitive journey that everyone has experienced at least once, a transient journey, and strange but familiar memories that you promised yourself not to think about but constantly reappear in your mid. This is not a “way of replay” that awakens basic personal experiences but a road that recalls traumas that we all share as a group.

Koo expresses that Way of Replay is used as “an allusion to a preference for ceaseless repetition of sections” as well as a means to “intervene into a situation in which the relationship between physical experiences that respond organically to spaces and memories of things perceived through our eyes breaks apart without much conflict.” For instance, in the case of the non-orientable loop that influences this work, if we link form with function, it is regarded as a sort of gyroscope that acts as a device that sets a sense of direction inside our physical body. Similar to the fundamentals behind a spinning top, it is an apparatus that sustains balance in spite of leaning. Similar to the principle behind a gyroscope that maintains its central balance despite seeming precarious, participants that walk along the “way of replay” experience an eerie vertigo, a dangerous obsession, and a sense of amusement.

II. Visual Apparatus of the “Time Track”: Amusement and Ilinx/Vertigo

On the way from Seoul to the Gwacheon National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, you pass by Seoul Land. I remember riding the Koggiri Train (Elephant Train) to the museum. One wing of the museum was hosting an exhibition of eminent Korean contemporary artists and on the other side was a screaming crowd going on amusement park rides and enjoying recreational culture. The two different sides – museum on one side and an amusement park on the other – composed different emotional axes. Seoul Land, as the artist explains, “is a place of dreams where people buy a ticket and strive to make the most of a day’s experience in which they must get on as many rides as possible within a designated time period.” Especially for people who felt that their daily routines were far removed from the arts, the two locations – the museum and the amusement park – did not come across as similar concepts. We tend to perceive art museums as an intellectual space where people build a sophisticated palate and knowledge, and amusement parks are seen as an entertainment space that brims with joy, excitement, and leisure. In a way, both are products of the modern era. Furthermore, in theory, culture and leisure are not separate, but in our memories and education the two undoubtedly exist as distinct concepts. Nonetheless, by creating a “playground for adults” inside the museum, Koo’s work raises a sense of amusement, momentary ilinx/vertigo, as well as dizziness.

In 1968, Phalle Nielsen’s The Model – A Model for a Qualitative Society (Modellen. En modell for ett kvalitativt samhalle) turned the Moderna Museet Stockholm into an adventure playground.3 Anyone, regardless of gender or age, could participate in the playground; against the conventions of the museum, this work attempted to transform a space intended to display visual objects into a place that deals with socialistic implications. The difference between Nielsen’s and Koo’s works was that Nielsen’s playground only permitted children. Even kids accompanied by their parents had to enter the playground alone. Ten years prior to Nielsen’s work, in 1958, Roger Caillois, in his Les jeux et les hommes: Le masque et le vertige, describes that games instantaneously sabotage perceived stability, awaken panic within our distinct consciousness, and destroy our sense of security using shocks and spasms.4 The illinx/vertigo that arises from Caillois’ explanation appears in all rides, such as swings or slides, that allow people to feel a momentary sense of speed. This emotion is a mixture of fears and jouissance (joy) that people can easily perceive at amusement parks or playgrounds. Thus, it is a subtle feeling that accompanies instantaneous delight and fear. Due to this dual-sided emotion, amusement park rides induce vertigo as well as a desire to repeatedly go on rides. They induce ilinx – which refers to breaking away from a stable perception – and, in turn, arouse dizziness or vertigo. As Johan Huizinga wrote in 1938, humans are instinctively homo ludens (humans of joy), playing is separate from our daily lives and specific rules and regulations exist, and they create completely unpredictable factors that are coincidental and accidental. Koo’s current work resembles the “playground” model and, hence, is filled with dangerous elements that trigger momentary escapes and vertigos resulting from riding amusement park rides. Within this playground-like structure that Koo installed inside the museum, such psychological elements coexist with fear and jouissance.

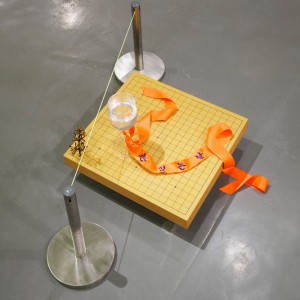

Koo’s Helter Skelter exhibition at the Atelier Hermes in 2012 revealed a similar playground structure. Helter Skelter is a helically shaped playground. On the 2012 exhibition catalogue, Koo is quoted as saying, “as a phrase, “helter skelter” reminds me of skyscrapers or helically shaped slides in amusement parks; in the dictionary, this phrase signifies a disorderly situation or a visually confused state.”5 Images that resemble helter skelter include easily searchable images of slides in the United Kingdom or the United States, as well as images of an upside down cone-shaped ice cream. The cone-shaped three-dimensional structure of Helter Skelter is transformed into Way of Replay, a more detailed configuration that people can get on and ride like a slide. Way of Replay is a structure made of iron and wood that is intended for people to walk on. On the other hand, Helter Skelter looks like a multiple layer of mosquito repellent incense. The fragments that fall from the burning incense create a circular archipelago; and two round incenses that are attached together resemble a gyroscope. The witty combination of the gyroscope’s steadiness and the frailty of the incense create an element of irony.

Other than the shape of the structure, Koo’s 2008 exhibition also conveys the themes of amusement and games. For the production of The King Fish, she visited a fishing site and recorded the people who were there to fish as well as the workers. Fishing is a form of leisure activity that people, especially men, have enjoyed since the ancient times. It began as a form of labor for primitive people living in the wild and has now become a type of recreational activity. Outdoor fishing has been transformed and expanded to include indoor fishing. Indoor fishing involves “fabricated nature,” which is a means of bringing nature indoors. According to Koo, “Fishing is a kind of static outdoor hobby that people have enjoyed for centuries, all the while thinking that fish is part of natural gift,” and it has changed into “a kind of virtual game as declined and analogue-era business, where ownership and possession, unlike pastime, have become the purpose.” In her work, the following unique elements exist: nature-object, nature-nature, nature-fabricated nature.6 Amusement and games have coexisted throughout the history of mankind as well as during civilization. However, industrialization has led to the institutionalization, industrialization, and capitalization of amusement; and along with this transformation, amusement has morphed into video games and entertainment with monetary goals. Considered a gift by many, fishing has endured the transformations of mankind. The same “gifts” that Marcel Mauss valued the most among the features of primitive culture were turning into barters and exchanges of materials and products in Western culture. People yearn to leave the city in search of happiness, tranquility, and relaxation from nature; however, people have substituted natural elements with economic ones. Expressions like games, gifts, and cultural products and themes of amusement and game have hitherto appeared consistently in Koo’s works. In particular, the devices implemented in Way of Replay arouse our conscious- and unconscious-level tensions during the moments that we subconsciously monitor the track for fear of getting lost. According to Caillois, seeking amusement is a basic human instinct and has accompanied us throughout our culture. Moreover, the suppression of ilinx leads humans to become addicted to alcohol or drugs.7

III. Composite Editing, Synthetic Experience

Throughout her works so far, Koo has focused on composite editing. Specifically, she has been compiling contradictory, non-interacting features in peculiar ways. Instead of simply editing images, she takes different forms of stories or formations of images and crafts structures that seek to synthesize these seemingly dissimilar aspects inside a single space. Rather than synchronizing or integrating two images or two stories, she restricts them from taking on complete individual importance and begins a sliding operation. It is meaningless to examine the characteristics of Koo’s tendencies, because each of her works boasts a sense of singularity.

During a 2006 interview with curator Alexis Vaillant, Koo revealed that, while studying at Yale University, she learned video editing and explained that video is “a forceful tool that extracts narratives of themes.” Bringing together videos, installations, sculptures, and minimal objects, Koo’s works are inspired by ordinary events. Once she is captivated by a certain topic, she surfs the Internet and discovers various associated images and contents. When ordinary realities meet digital media, which is characterized by hypothetical compilations, intrinsic meanings and intensions experience constant adaptation and new narratives are produced. Koo’s 2008 solo exhibition, titled Synthetic Experience, seems to make the best use of gathering information using the computer and using images floating on the Internet as data. Koo does not seem to be particularly concerned with the fundamental differences between nature and artifacts. In fact, scenes fabricated by Koo induce an illusion that makes it seem even more authentic than the real thing. For instance, the scenery portrayed in her Under the Vein; I Spell on You – revealed during the 2012 Spell on You exhibition at Media City Seoul – resembles an actual garden. Had the audience been unaware of the fact that the creek in the garden was artificial and the water was supplied by City Hall, they would have been completely deceived.

“Composite” was not a widespread feature in the world of analogue works. For her 2008 Souvenir exhibition, Koo combined disparate spaces, times, and places to create a Kinkaku-ji replica that seemed inexplicably realistic. In addition, she searched through national natural heritage websites and compiled data to create Natural Monument – Geological Features and Minerals of South Korea; this work is presented as a cave characterized by “hybrid beauty and an eerie artificiality”.8 The original Kinkaku-ji that inspired the Souvenir exhibition was destroyed in a fire, and a “restored” Kinkaku-ji that retains the original form of the temple remains. Hoping that the image of the actual Kinkaku-ji will continue to be endlessly recycled in any form9, Koo reads Mishima Yukio’s novel, The Temple of the Golden Pavilion, and gets to see the Japanese Kinkaku-ji. However, she is not able to feel anything from the image itself. Although it is just a souvenir shaped like the Kinkaku-ji, Koo is able to portray her sense of mental estrangement by using a mirror to create an endless reflection, thereby juxtaposing the actual image against the interpreted image in her mind.

Walter Benjamin’s aura is present in the restored Kinkaku-ji, and the destroyed original Kinkaku-ji exists in another form after going through a restoration process. “Composite” editing and “synthetic” experience – although Koo denies the idea of regulating work methods by assigning them simple terms – serve as guidelines for understanding her work. She says, “In an age when immense amounts of images and information erupt like a giant fountain, routinely witnessing the change of established, seemingly eternal values and convictions into clichés in just five minutes, I realize that within this banality lies the irony that status changes depending on perspective. Observing such elements – recombining them, and then producing images through different kinds of physical transformations – is my working method.”10 Using this method, she compiles digital and picturesque forms in an eerie way. Witness – her 2010 exhibition, for example, is a giclée print on canvas; this rather kitschy artwork uses a computer to combine images of religious roads from specific religious websites. Diverse kinds of animals and plants depict artificial scenery; this shining global landscape is quite grotesque but is also like a “barber shop picture.” Analogue images, words, and images found using a computer are all ingredients that jumble together and become connected to generate completely unexpected objects of meaning. Similar to how contemporary musicians collect various noises and conversations to compose music, Koo gathers data that floats around like zombies on computers or in our everyday lives and uses them as scenarios or materials. Consequently, Koo majored in sculpture but I have yet to see a sculpture made by her in her studio. Koo considers information as a medium that possesses the power to disseminate information to anyone.

The use of the composite method is evident in Overloaded Echo, Koo’s 2006 exhibition that utilizes HD single channel video. The production for this work began in 2004 during her stay at the Akademie Scholoss Solitude as the artist in residence, and it can be traced back to the time of the Kim Sun-il execution. Although the video of the execution was censored in Korea, the video floated around like a zombie on various overseas websites. As a result, many people observed the event and used the images without any hesitation.11 Even without reference to this story, we are able to feel the man’s anguish and desolation through the transient images. A naked man wearing a mask is ceaselessly rotating on top of a round table. While he cannot see us, bystanders are looking at his repetitive movements with an inquisitive gaze, as if all this does not concern them. The onlookers appear to be the culprits and the masked man in the middle seems like the victim; however, like a wavering string, this arrangement can easily change at any moment. At first glance, this production does not give the impression that Koo tenaciously deals with social issues; however, Koo is known to be a very scrupulous commentator and a realist that represents our generation. The artist, certainly, is not going to agree to such titles or give them meaning. The foundations of her work lie in the aesthetics of negation; she does not start her projects with aesthetics in mind and feels far removed from creating official manuals or statements used to facilitate the process of understanding her works.

In the age of post-medium – exemplified by ranking order of images, information editing methods, and positioning systems, Koo gathers images and data drifting around Twitter, Facebook, and other social media in order to form a spectacular story, not just one story believed to be true. She uses all this data and information in an effortless manner, as if they were clay or paint. In a way, this world is filled with various raw materials that could be used for her work; as both an observer and a constituent that interprets social gaps, she makes use of the physical attributes of digital media. Scattered images turn into artificial landscapes and synthetic compilations that challenge the true nature of our spaces, locations, as well as perceived visual realities. We often use the expression “our generation” when referring to Koo’s works. Contrary to the intensions of the artist, generational themes mingle and interact. The selected combination of words and phrases do not carry a single meaning or nuance but, instead, emphasize polysemy; as a result, we come across serendipity.12 Some describe Koo’s video work as “theatrical13,” but her works occasionally cause dyslexia. Even though her video installations lack a coherent story, viewers that are familiar with her storytelling style strive hard to uncover whatever they can through the characters’ gestures and behaviors. Her production is not a story with a distinct beginning, middle, and end. Instead, it exists as a single scene or a series of tableaus. In the museum, the audience attempts to figure out her work by looking at the constant replay of the videos, but they must realize that, at times, the video itself is a single image, a momentary impression that you encounter, or just a glance.

In such a world, Koo may be tackling the widespread visual arts tendency that overly emphasizes the visual aspect at the expense of temporal, spatial, and locational elements. With a single stroke, she dishevels our understanding of the empty canvas-like space of infinite possibility and the modern sense of time that prioritizes linearity and rationality. For her 2007 Blind Full Moon exhibition, composed of 12 C-prints, she took photographs with her eyes closed. Blind Spot, which was shown at Plateau, revealed a video that she recorded inside an enclosed space; she recorded the video with her eyes closed, so as to convey that she felt the space instead of seeing it.

IV. The Absurd: And the Unfinished Story

Koo recreated a given space by hypothesizing it as a “time track.” Viewers are impelled to break away from the customary movements and behaviors that they are accustomed to inside museums. It is difficult to walk with your back straight on this track that barely fits two people. You must bend your body forward and focus on seeing spaces horizontally, rather than vertically. This horizontality of vision offers a view of “a flat hexahedron devoid of natural light” and disturbs our sense of vision and time.14 In Albert Camus’ philosophical essay, no matter how many times Sisyphus shoves the boulder up the hill it rolls back down; similarly, in Way of Replay, no matter how many times you follow the track, the dead-end presents itself as another “way of replay,” reminding us of the reality of the absurd. Koo’s work cannot be condensed into a compressed, simple expression. This architectural structure that directly engages the audience can be a ride that offers amusement, vertigo, felicity, as well as shrieks; at the same time, it can also be a warm and cozy cave-like shelter.