Kim YoungEun

Interview

CV

Born in 1980, Seoul

Lives and works in Santa Cruz and Seoul

Education

2021–present

Ph.D. Candidate in Film and Digital Media, University of California Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, USA

2013

Certificate in Sonology, The Royal Conservatoire of The Hague, The Hague, The Netherlands

2007

MFA in Fine Arts, Korea National University of Arts, Seoul, Korea

2004

BFA in Sculpture, Hongik University, Seoul, Korea

Selected Solo Exhibitions

2022

Frames of Sound, SONGEUN, Seoul, Korea

2019

Bones of Sound, Visitor Welcome Center, Los Angeles, USA

2014

Bespoke Wallpaper Music, Solomon Building+CAKE Gallery, Seoul, Korea

2011

Room 402, Seoul Art Space Mullae, Seoul, Korea

The Units of the World according to ;Semicolon, Project Space Sarubia, Seoul, Korea

2009

Lesson for a Naming Office: Chapter 1, Alternative Space Loop, Seoul, Korea

2006

Listeners, Insa Art Space, Seoul, Korea

Selected Group Exhibitions and Screenings

2025

Korea Artist Prize 2025, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea

2024

PANSORI, a Soundscape of the 21st Century, 15th Gwangju Biennale, Han Hee Won Museum of Art, Gwangju, Korea

2023

Beyond the Crest, M+ Museum, Hong Kong

Image Forum Festival, Theater Image Forum, Tokyo / The Museum of Kyoto, Kyoto / Aichi Arts Center, Nagoya, Japan

Monitoring: This Image Will Become Important Later, Kassel Documentary Film and Video Festival, KulturBahnhof Kassel, Kassel, Germany

Ji.hlava International Documentary Film Festival, Prague, Czech Republic (Online Screening)

Jecheon International Music & Film Festival, Jecheon, Korea

Asian American International Film Festival, New York, USA

Real DMZ Project, kHaus, Basel, Switzerland

2022

Past. Present. Future., SONGEUN, Seoul, Korea

2021

Signaling Perimeters, Nam-Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

Humming to the Sound of Fear, Helen J Gallery, Los Angeles, USA

Border Crossings: North and South Korean Art from the Sigg Collection, Kunstmuseum Bern, Bern, Switzerland

2020

IAS 2000–2020, Insa Art Space 20th Anniversary Archive Project, Insa Art Space, Seoul, Korea

Artists in Their Times: Korean Modern and Contemporary Art, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Gwacheon, Korea

COLA 2020, Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery, Los Angeles, USA (Online Exhibition)

2019

LOOP Discover Award, Center Civic Convent de Sant Agusti, Barcelona, Spain

Sharjah Film Platform, Sharjah, UAE

2018

Unclosed Bricks, ARKO Art Center, Seoul, Korea

2017

17th SONGEUN Art Award, SONGEUN Art Space, Seoul, Korea

The Melting Sea, Art Space Pool, Seoul, Korea

2016

X: Korean Art in the 1990s, SeMA Gold, Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

Art Spectrum, Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

2015

Klingsor’s Last Summer, HITE Collection, Seoul, Korea

Radiophrenia, Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, UK

Selected Lectures and Presentations

2024

“GB Talk,” Gwangju Biennale, Gwangju, Korea

“Sound and Writing in East Asia,” Center for East Asian Studies, University of Chicago, Chicago, USA

2023

“Atmospheres of Violence,” Department of Art, Film and Visual Studies, Harvard University, Cambridge, USA

“Arts and AI Innovations,” Science & Justice Research Center, University of California Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, USA

2022

“Differentiating Sound Studies: Politics of Sound and Listening,” Music Research Center, Hanyang University, Seoul, Korea

2020

“How to Collect Time – Please bring your work saved on an external hard drive,” Nam-Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

2019

“Ear Level: Sound and Museum,” SeMA Nanji Residency, Seoul, Korea

2016

“Listening to Space,” Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

Selected Awards and Grants

2023

Korean Competition Short Winner, Jecheon International Music & Film Festival, Korea

2020

City of Los Angeles Individual Artist Fellowship, USA

2017

Grand Prize, SONGEUN Art Award, Korea

Honorary Mentions, Prix Ars Electronica, Austria

2014-2015

Mondriaan Fund Fellowship, The Netherlands

Selected Residencies

2018

Q-O2: workspace for experimental music and sound art, Brussels, Belgium

2014-2015

Rijksakademie van beeldende kunsten, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Selected Collections

Jeju Museum of Contemporary Art, Korea

Museum of Contemporary Art Busan, Korea

National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea

Seoul Museum of Art, Korea

The Sigg Collection, Switzerland

Critic 1

Kim YoungEun and Sounding the Fray

Casey Mecija (Assistant Professor, Department of Communication & Media Studies at York University)

There was also a special quality to our wind. [...] Eventually, my ear would become attuned to background noise. And even, or perhaps especially, when you are explicitly taught to keep quiet and not ask too many questions, you can’t resist pulling on that thread of familiar silence once the edges of the fabric have begun to fray.

— Grace M. Cho, Haunting the Korean Diaspora

Kim YoungEun has, for the past twenty years, shared a multidisciplinary practice that inaugurates intimate contact with Korean histories of sound. Employing “sonic ethnography,” the sounds collected and staged across her expansive portfolio elaborate the complex psychic, sensory, and historical specificities of time and place.1 Pulling on the threads of Korean legacies of militarism, migration, and diasporic relationalities, sound fills the gaps in perforated narratives disavowed by colonial violences, processes of modernization and their concomitant sensory hierarchies. Across the work, Kim’s conceptual interventions antagonize Western regimes of perception that overemphasize vision as the locus of knowledge. Alongside her critique of the hegemony of vision, Kim also importantly draws attention to how listening modalities are inscribed by racialized logics. Emerging from these inquiries is a vigorous archive of aurality that reveals sound as a quotidian remnant of often suppressed or underrecognized sociopolitical and historical contexts. For Kim, the sonic paradigm offers ethnographic entry points through which audiences might differently attune to what Grace M. Cho might describe as “the edges of the fabric [that] have begun to fray.”2 It is precisely within the fray of colonial imposition that sound resonates, and listening becomes a form of imagining and enacting otherwise.

Scholars and artists alike have argued that listening is more than focused attention; it is also a process of becoming aware of how ideology may creep into the act of listening itself.3 Xochitl Marsili-Vargas suggests that “while listening is an act of interpretation, it also entails occupying a particular social space, a way of being in the world.”4 The listener’s context is distinct and thus institutes agency over how a given sound is codified and represented. But listening to sound is not without ethics or responsibility. According to Kim, a question that guides her practice remains: “What possibilities can listening offer in knowledge production and decolonization processes?”5 In many of her works, Kim’s “sonic ethnographies” seek to represent, with care and fidelity, the overlaps of history and acts of political dissent that resonate beyond official state narratives. Notably, this methodology observes sounds in all modalities, from text to music to environmental and paralinguistic. Throughout her practice, Kim assigns unique significance and transformative potential to sounds thought to have none or that evade the immediacies of legibility.

What can Sound?: Exploring “Phonic Substance”

Lesson for a Naming Office: Three Treatments (2009) is a book that contains treatments for three videos created by Kim between 2009 and 2011. Conventionally, a treatment is a written document describing a video project’s overall concept, storyline, and stylistic approach. The treatment is also an opportunity to introduce characters and share narrative details before production. This book and its related video trilogy feature unlikely protagonists in the form of punctuation, speech utterance, and phonetic signs. For example, In “Chapter 1: Oral Ground” (2009), text is laid out like a novel. The opening line reads: “Drrrrrrrrr –” The lines that follow describe a child making sounds with their tongue to mark the beginning of a game. The word “magma” is introduced and then repeated fifteen times successively. The last line on the page reads: “The word gradually loses its meaning as much as it is repeated.” According to the artist, in this chapter, each page documents an event scene that showcases a sound, a sign, a phonetic symbol, and their related signified object, all derived from a single word. The withholding of pragmatics and the airiness on the page encourage co-authorship with its audience. “Magma” becomes a shapeshifting protagonist whose plotline is indeterminate without our participation. The performative frame loosens the relationship between sound, sign, word, and referent, creating opportunities for different stories or relations to the work to emerge.

In the treatment for “Chapter 3: The Units of the World According to ;Semicolon” (2011), the protagonist, the semicolon, is tasked with formulating a report on its fellow punctuation marks. Each punctuation mark (for example, the hyphen or ellipsis) demarcates specific roles and functions within a sentence. However, punctuation marks are soundless despite their formative impact on language and how it is communicated and comprehended. One page describes semicolon’s encounter with colon; “It was easy to meet him. As he was living near me, I come across him from time to time. […] I was once seriously jealous of him. He was doing a sacred job of designating John 3:16 or Romans 5:18.” By ascribing voice and character to punctuation marks, Kim culls “phonic substance” from the image of words and signs.6 Stretching the imagination, the semicolon is filled with personality, offering the audience intimate insights into the protagonist’s ideologies and psychic life. Through this challenge of semiotics and its sensory constraints, the sounds and signs that constitute language are emphasized as flexible social and material forces. When manipulated, the arbitrariness of their relations is exposed, and the “almost the same, but not quite” of linguistic hegemony is playfully enacted.7

(Re)sounding History

In 2014, from September 28 to December 14, the Umbrella Movement staged a seventy-nine-day pro-democracy occupation of Hong Kong’s commercial districts. The opening of umbrellas to shield from police pepper spray and tear gas would become a lasting signification of the protestors’ sustained and non-violent actions. As with most protests, demonstration sites are often sonically animated by speeches, activist chants and political slogans. However, an unlikely sonic tactic emerged when a protester, intent on diffusing tensions between demonstrators and disgruntled opposition, accidentally activated a rendition of the song “Happy Birthday” over their megaphone.8 The accident is met with a momentary hush from the crowd, followed by spontaneous applause and the singing of “Happy Birthday” in Cantonese, until the counter-protesters leave the scene. This “nonsensical soundscape”9 would become a global political strategy for protestors to de-escalate potential violence and inspire the creation of Kim’s work titled Flesh of Sound (2015–2019).

Described by Kim as “a small, accidental event [that] gained symbolic power through the collective voice,” Flesh of Sound examines the recontextualization of “Happy Birthday” as an immaterial sound that, through collective participation, is transformed into an embodied tool of resistance. A recording begins with a single voice humming the melody of “Happy Birthday.” Repeating at regular intervals, the voice is gradually overlapped to accumulate and form a chorus of voices. With each additional recording, the once singular voice grows in depth, weight, and dynamics. “Happy Birthday” and its association with celebration are transformed through contextual incongruence and collective expression. The materiality of collective voices is examined as a potent tool for mediating meaning. But in this context, the fleshiness of sound is recalcitrant; it makes meaning possible but does not create it. The fortuitous mistake of a mispressed button and the collective singing that followed illustrate that it is through corporeality and the specificity of context that the signification of the song and the voices that sing it are transformed. Winnie W. C. Lai shares that “dissenters have to recontextualize the sound with their current existence as physical bodies in the protest space. In other words, they must ruminate on their roles and actions as political participants.”10 In Flesh of Sound, the singular voice transforms into a collective body, and it is through the accumulation of voices that Kim gestures towards the sonics of political possibility.

While sonic ethnographies of resistance can be gleaned across Kim YoungEun’s catalogue,11 she does not take for granted that voice and sound are also tools used to fortify militarism and facilitate violence and war. In 2017, Kim exhibited Guns and Flowers (2017), a sound installation inspired by the loudspeaker systems that line Korea’s Demilitarized Zone DMZ, a heavily militarized de facto border between South and North Korea. After the signing of the Korean War Armistice Agreement in 1953, which symbolically halted the war for control over the Korean Peninsula between Chinese and Soviet-backed communist forces in the north and the American-backed government in the south, the two Koreas remain in a latent state of conflict. Both North and South Korea maintain a significant military presence on either side.

Described by Kim as examples of “sonic warfare,” the two countries strategically positioned loudspeaker walls on opposing sides with the intent to transmit propaganda and blast sounds like music, global news, military marches and even the sound of howling wolves and the clang of gongs deep into opposing territory. It has been reported that the high-powered speakers can project sound over a distance of more than twenty kilometers (12.4 miles). The sounds emitted by these speakers cannot be contained by the Military Demarcation Line MDL that partitions the north from the south. Sounds travel; they swell, diminish, and puncture. They evade territories and enemy lines. Reverberations are indiscriminate (sometimes relentless) and will bombard regardless of content and form. Sound engages all the senses and lingers in the psyche. Its multisensory capacities call for attention to the body, posing inquiry into the felt dimensions of sound. Describing warfare as sensual seems counterintuitive, as it is a word often associated with experiencing pleasure. But as Amber Musser argues, the sensual orients attention to “felt details” and the ways in which “flesh summons its own ways of knowing.”12 It is through full-body contact with sound that Kim elicits a more sensuous and synesthetic sensitivity in ethnographic engagements with borders.13

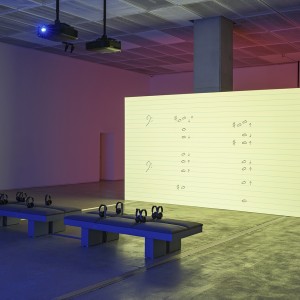

In Guns and Flowers, Kim reconstructs a listening experience inspired by the weaponization of sound through the form of the popular love song. The incongruence between the widely perceived intent of love songs, as sounds that evoke emotional associations with romance, and the method and context in which they were deployed highlights how any sound can be mechanized to prompt sensations of fear and domination. The installation features five horn speakers positioned atop speaker stands arranged in a V-like configuration. A four-minute loop constructed of sounds extracted from popular love songs used by the South Korean military is edited and rearranged. Kim YoungEun was particularly struck by how the loudspeakers created a material experience with these songs. She describes these amplified sounds as “a tactile sensation with the energy of vibrating air working remotely to beat one’s eardrum—just as a bullet shot from a distance has a physical effect on its target.” The weaponization of these love songs physically impacted bystanders in their line of fire. Their melodies were blasted with such force that even as their aural qualities diminished, their vibrations lingered with the listeners’ bodies.

Nina Sun Eidsheim refers to sound as an “intermaterial vibrational practice” that shapes our relations to one another.14 The loudspeaker broadcasts created distress for soldiers and the people living in communities along the border. With Guns and Flowers, Kim reconstructs this sensory experience through the process of audio “sculpting.” Using a spectrogram, which provides a visual representation of audio, Kim extracts frequencies from one of the love songs, resulting in an audio loop of fragmented and percussive sonic jolts that, at times, ring at discomforting levels. The sounds “attack” listeners at varying pitches and timbres, subverting any associations with love that the music may have originally intended. The piece was received with critical acclaim and earned Kim the grand prize at the 17th SONGEUN Art Award, a prestigious annual accolade granted by the SONGEUN Art and Cultural Foundation.

“Ear Training”: Sound & Listening as Sociopolitical Terrain

In 2022, a series of works which includes Ear Training, A Story of Oseonbo: Sounds Lost in Translation, and Brilliant A, Kim YoungEun continues to examine the overlaps of histories of sound and listening as mediated by processes of modernization and colonial incursion. In Ear Training, Kim grapples with Korea’s history of music education by staging pitch-perception exercises inspired by Japanese military training aimed at developing soldiers’ pitch and rhythm recognition of enemy airplanes and submarines. The reenactments draw from soldier scores, audio recordings, interviews, and academic research to recreate soundscapes experienced by the Japanese Army and Navy during its occupation of Korea. Through the reconstruction of these exercises, Kim draws attention to the militarization of the senses as weapons of war. A Story of Oseonbo also turns to historical archives to highlight another form of perception training in Korea. The forty-seven-minute, single-channel video tells the story of the first scorebook that was transcribed by a Korean musician into Western notation in 1914. The process of translation between these systems leaves the original score full of erasures and distorted interpretations. Turning to experts in traditional Korean music, Kim reassembles the compositional elements extracted through Western annotation. The audience is left with a powerful reminder that translations leave elisions shaped by cultural dynamics of power and engineered by histories of racialized dispossession and loss.

The institutionalization of Western music is also examined in the video Brilliant A. In its opening scene, a large wooden crate is tied with rope and pulled across the shore of a beach by an unknown force outside the frame. While this happens, a narrator shares: “March 26, arrived at Samun and the piano was already on shore, we were devoutly thankful for this.” Drawing from a historical archive of early 20th century materials, the video recounts the arrival of the first piano in the city of Daegu, Korea, along with the introduction of the pitch system foundational to Western music. It’s widely believed that Western music was brought to Korea by Protestant missionaries near the end of the 19th century.15 The piano was shipped via Samunjin Port to missionaries Richard and Effie Sidebotham. The instrument was referred to as “the ghost-barrel,” an allusion made by Korean bystanders about the “strange sounds” that were emitted by the wooden box.16

Pitch A corresponds to an audio frequency of 440 Hz, which is the standard pitch preference for tuning most modern musical instruments. Tuning instruments to higher frequencies creates crisp and clear sounds. In line with Western preferences for “brighter” music, the piano and its related musical standards would shift taste and auditory preferences from Korean traditional music toward the modern standards of Europe and the United States. The piano would symbolize a privileged elite in Korea and serve as a pathway supporting a political shift toward modernization. The instrument would also maintain an inseparable connection to missionary work and religious education. As a means of proselytizing, Western music played a role in Christianizing the country. It would contribute to a process of training Koreans in music and Christian ideologies from the United States.17 In Brilliant A, Kim reconstructs a significant moment in history that points to some of the sociopolitical consequences of the piano’s emergence in Korea. The introduction of Western music altered Korea’s traditional values and would forever shape Korean experiences of sound and listening in the contemporary moment. The global dominance of the piano, along with the sounds and education it embodies, is not an innocent figure in history but a “strange” cog of Western assimilation that, if attuned to differently, reveals sensory regimes of knowledge, prompting speculation about what has been lost and what could have been.

Listening to Diaspora

What listening genealogies emerge when sound is situated in time and space? How do we listen to histories of trauma, and what are ethical responses to its embodiment? What does diaspora sound like? Sounds carry data, and it is through listening that we process and communicate this information. However, we know that listening is not a neutral act. Listening “is an interpretive, socially constructed practice conditioned by historically contingent and culturally specific value systems riven with power relations.”18 In Kim’s most recent work, the artist expands her sonic ethnographic approach to the Korean diaspora. Focusing on language, music, and the everyday aural events of Korean diasporic communities, Kim considers how histories of migration produce distinct modalities of listening. Writing about the Korean diaspora in the United States and the aftermath of the Korean War, Grace M. Cho describes the Korean diaspora as “transgenerationally haunted.”19 She writes that the Korean diaspora is “constituted by unremembered trauma and loss. When an unspeakable or uncertain history, both personal and collective, takes the form of a “ghost,” it searches for bodies through which to speak [and is] distributed across the time-space of diaspora.20 Giving form and sound to traumatic histories of violence and displacement, Kim’s aesthetic practices communicate a multiplicity of narratives that point to the “haunted spaces” of Korean diasporic experiences.

Go Back To Your (2025) is a single-channel video that immerses its audience in the sounds of racist violence experienced by Korean women in America. In the soundscape, amidst the sounds of falling rain, a voice is heard shouting, “Go back to your country.” The protagonists’ response to this racist invocation is displayed as text. She replies: “I hesitated for a moment, then walked toward you. You looked startled and took out your phone, threatening to call the police. I said, “I was born here.” The xenophobic call to return to a place one was never from is met with a response that, for the antagonist, provokes an unanticipated reaction that, coupled with her subjectivity, is also perceived as threatening. The affective charge of the statement “I was born here” elicits a defiant impulse towards subjection. Koreans carry histories of militarized violence and trauma that have led to erasures and silences, conditioned by unspeakable loss.21 Akin to Grace Cho’s methodology of writing to “flesh out the ghosts” of disavowed history, Kim YoungEun’s sonic ethnographies recognize that the trauma of racism is a “transgenerational haunting.” The text in Go Back To Your gives form to alterity and voices agencies that may have, in the past, been too painful to articulate.

For Kim, the soundscapes of the Korean diaspora urge listeners to jettison habitual modes of perception. These habits negate the ways in which diaspora disorders knowledge shaped by nationalist imaginaries. In the video titled Listening Guests (2025), Kim focuses on the diasporic experiences of members of the Koryoin (Soviet Korean) community in Korea and Korean immigrants in Los Angeles. In one scene, two middle-aged men sit at a table, reflecting on the disjuncture between how they are socially perceived in Korea and how their histories of migration have made them otherwise. One of the men shares: “I’m Russian. I even dream in Russian. That means I’m not Korean—I’m truly Russian.” Here, culture is described as a dissonant experience where the language one speaks and the rituals one enacts do not align with the normative expectations of assumed race and ethnicity. The man continues to describe the source of social perplexity: “We have to explain we’re foreigners. Sometimes people think we’re joking because we look Korean. So, in the market, I say, “I’m a foreigner. My Korean is limited. Please understand,” before I speak…We were born in Russia, but don’t look like typical Russians…”

Koryoin are ethnic Koreans from the former Soviet Union. The first generation of Koryoin migrated to the Russian Far East, fleeing famine, exploitation, bureaucratic control and later Japanese occupation. With this wave of Korean migration, the Russian Far East became a bastion of Korean culture, politics and anti-Japanese resistance. Following the Japanese invasion of China in 1937, Stalin perceived the Korean diaspora as a racialized threat to national security. In that same year, approximately 180,000 Koreans were forcibly deported to Central Asia by his regime.22 The Koryoin diaspora in Korea primarily comprises descendants who, following the establishment of official diplomatic relations between South Korea and the countries of the former Soviet Union, began migrating in the 1990s in search of improved economic opportunities. For many second-generation Koryoins and the generations that follow, “race” ties them to a culture and geography with which they share a ghostly affiliation through ancestry alone.

The film shares their struggle to learn and speak the Korean language, a collection of sounds and symbols that, for them, mark contradictory terms of belonging to the diaspora. The sound of Russian explicitly marks them as foreigners in Korea, but it also connects them to history, family, and community. In this work, along with many other pieces found in her archive, Kim YoungEun invites audiences to engage in critical listening practices that anchor sound in relationality. In Listening, Thinking, Being: Toward an Ethics of Attunement (2014), Lisbeth Lipari writes that it “requires courage to listen for the not-already-known, and in so doing, reveal our own particular vulnerability and weakness.”23 Following Kim, if we take the ethnographic capacities of sound seriously, we might bravely confront the humbling realization of our ignorance. It is from these frays of knowledge that more ethical approaches to how we sense and make sense of others enable new and, hopefully, more just forms of being together.

1. For uses of “sonic ethnography” see Steven Feld’s 2004 interview with sound artist Don Brenneis, where Feld questioned if anthropology could be imagined in sound rather than about sound. Also, see Ernst Karel’s work, a practitioner of sonic ethnography who uses recording, editing and composition to create nonfiction sound works. Steven Feld, and Donald Brenneis, “Doing Anthropology in Sound,” American Ethnologist 31, no. 4 (2004): 461–474; Ernst Karel, “Notes on ‘Space of Consciousness (Chidambaram, Early Morning)’,” Anthrovision, no. 4.2 (2016).

2. Grace M. Cho, Haunting the Korean Diaspora: Shame, Secrecy, and the Forgotten War (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008), 2.

3. Don Ihde, Listening and Voice: Phenomenologies of Sound, 2nd ed. (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2007); Christine Bacareza Balance, Tropical Renditions: Making Musical Scenes in Filipino America (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016); Nina Sun Eidsheim, Sensing Sound: Singing & Listening as Vibrational Practice (Durham: Duke University Press, 2015); Alexandra T. Vazquez, Listening in Detail: Performances of Cuban Music (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013).

4. Xochitl Marsili-Vargas, Genres of Listening: An Ethnography of Psychoanalysis in Buenos Aires (Durham: Duke University Press, 2022), 33.

5. Kim YoungEun, from the Artist Statement.

6. Fred Moten, In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003).

7. Homi Bhabha, “Of Mimicry and Man: The Ambivalence of Colonial Discourse,” October vol. 28 (1984): 125–133.

8. Michele Fan, Doug Meigs, “The Umbrella Movement Playlist,” Foreign Policy – the Global Magazine of News and Ideas, Oct. 9, 2014, https://foreignpolicy.com/2014/10/09/the-umbrella-movement-playlist/.

9. Winnie W.C. Lai, “‘Happy Birthday to You’: Music as Nonviolent Weapon in the Umbrella Movement,” Hong Kong Studies 1, no. 1 (2018): 73.

10. Ibid.

11. More examples of Kim’s sonic ethnographies of resistance include Tripartite Confrontation (2013), Ballad (2017) and Echo Chamber (2020).

12. Amber Jamilla Musser, Between Shadows and Noise: Sensation, Situatedness, and the Undisciplined (Durham: Duke University Press, 2024), 7.

13. L. S. Min, North Korea So Far: Distance and Intimacy, Seen and Unseen (Ph.D. diss., UC Berkeley, 2020), 145.

14. Nina Sun Eidsheim, Sensing Sound: Singing & Listening as Vibrational Practice (Durham: Duke University Press, 2015), 3.

15. Jeongseon Choi, Western Music in Korea with an Emphasis on Piano Compositions since 1970 (Ph.D. diss., University of Maryland, 1997).

16. Robert Neff, “Daegu and the Legend of Korea’s First Piano,” The Korea Times, Mar. 18, 2022, https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/opinion/20220318/daegu-and-the-legend-of-koreas-first-piano.

17. Choi, Western Music in Korea with an Emphasis on Piano Compositions since 1970.

18. Jennifer Lynn Stoever, The Sonic Color Line: Race and the Cultural Politics of Listening (New York: New York University Press, 2016), 14.

19. Cho, Haunting the Korean Diaspora.

20. Ibid, 40.

21. Ibid.

22. German N. Kim, “Koryo Saram, or Koreans of the Former Soviet Union: In the Past and Present,” Amerasia Journal 29, no. 3 (2003): 23–29.

23. Lisbeth Lipari, Listening, Thinking, Being: Toward an Ethics of Attunement (University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2014), 206.

Critic 2

A Keen Ear Attuned to Form

Carlos Quijon, Jr. (C-MAP fellow for Southeast and East Asia at the Museum of Modern Art in New York)

Across Kim YoungEun’s practice, forms emerge from an assembly of sonic and acoustic materialities: from the traditions and technologies of creating sound; its various addresses; listening and responding to it; the ways in which it materializes a social space or relations mediating its circulation or its place in the history of culture. Throughout Kim’s practice, we see the artist lean into questions around how sound is sensed, made sensible, and creates sensible form. Sound carries through atmosphere, through walls, across spaces, suffuses, and signifies (whether its source is identifiable or not). In Kim’s work, sound takes form, conjures a world.

Sound, in Kim’s practice, is a scenographic and choreographic provocation: it enlivens objects, annotates space, distributes affects throughout, gathers bodies around and alongside. In other words, sound becomes a stimulus to arrange space and materialize an environment (scenographic) and a stimulus to organize bodies and allow these bodies to respond and act out (choreographic). In thinking about how sound becomes scenographic and choreographic in Kim’s practice, I pursue a related interface in the theorization of sound: the diegetic.1

While the discourse of the diegetic is mostly interrogated within the framework of the cinematic or the audiovisual, I find its discourse resonant in discussing these works. The diegetic in this instance escapes its coupling with the “nondiegetic” in cinematic discourse, a binary that cinema scholar Steffen Hven pries open. He explains: “Diegesis is experienced as our immediate, yet mediated, spatiotemporal environment. It is immediate in the sense of being manifest to us in its kinetic, material, affective, and semiotic presence.”2 Furthermore, he remarks: “The diegesis pertains to the entirety of the audiovisual structure, and any attempt to disassemble its parts into strict categories—e.g., diegetic versus nondiegetic, story versus discourse, content versus style—betrays our initial, multisensorial experience of the diegesis as the environment of the film.”3 For Hven, the way diegesis has been largely understood is as a textual premise—that elements of films work to flesh out a narrative that preexists the mediations of the audiovisual stimuli. This narrative takes priority and shapes the signification of the elements of the cinematic object. Moving away from this binary, Hven proposes the diegetic as a question of “ecological sensemaking,” a method of surfacing “a felt, mediated environment that comes alive through its encounter with the spectator’s embodied organism.”4

As a form of “ecological sensemaking,” I am interested in the reconsideration of the diegetic as “emergent on the basis of the spectator’s cognitive and affective capacities for sensemaking (turning the film material into a felt environment or affective ecology), but also how being embedded in media ecologies modulates not only our affective and perceptive capacities but also our general thoughts, feelings, and disposition.”5 Within this framework, cognitive and affective capacities coincide with their modulation through media ecologies. Sound becomes “our immediate, yet mediated, spatiotemporal environment” which structures our environment and our response to that environment. The scenographic and the choreographic unfold in and through these immediacies and mediations.

In an early work titled Tripartite Confrontation (2013), we see these tendencies interface. The work takes inspiration from the slippery polyvocality of Korean-American writer Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s novel Dictee (1982), where a narrator shapeshifts and speaks as Ryu Gwansun (a prominent activist in the March 1st Movement against Japanese colonial rule in Korea), a mother, “myself,” and Mother Teresa. Three objects are presented in the exhibition space: a telephone, an exhaust vent cover, and a framed photograph. Snippets of sound play at timed intervals in the space: the phone ringing, a barely audible whistle from behind the vent, knocks and thuds behind the photograph. Within this staging, we respond to each sound as a prompt, a provocation. Except for the telephone ringing, the sources of the sounds are not seen. The phone rings and as soon as one picks it up, the call ends. The relationship between sound and the object that we see in the exhibition offer us a range: the phone’s ringing is part of its function and is made by the object itself; the vent is a channel for the unidentified sound to travel, there is a possibility of sound traveling through from a different source; lastly, the photograph is neither an object of sound or a channel, and the relationship of sound and object proposes a different acoustic ontology—not of source nor object but mere coincidence. Each sound offers a scenography of sound-object-audience relationship. The experience is ecological: the gathering of these objects happens in this particular space, which is experienced by a feedback mechanism between the objects and the people who interact with them. The works are meant to be experienced in relation to one another.

The provocations of Tripartite Confrontation find compelling extrapolation in Bespoke Wallpaper Music (2014), a sound performance held at the Solomon Building, an old building in Seoul that used to be a market hosting small secondhand shops. Shop partitions create corners and enclosures and with them unusual vistas, skewed entry points, dead ends. Kim uses these architectural idiosyncrasies to create scenographies of sonic experience. Performers would hide themselves in these discreet spaces where they make sound, respond to a conductor’s signals remotely, and take cue from whatever faint sound they hear from the other performers. The audience sits in the same situation, trying to follow the performance through the faintest cues and the subtlest shifts. A choreography of bodies trying to listen and bodies trying to be heard structure the performance. Bespoke Wallpaper Music is an exploration of what the artist nominates as “aural spaces,” spaces where “visibility is obstructed [and] aural experiences take on a new identity, allowing the space to be sensed in an entirely different way.” She further explains: the physicality and placeness of aural spaces—what she describes as “visually featureless or entirely invisible spaces”—can only be revealed by sound.

An ecology of sound scenes shapes the experience of both Tripartite Confrontation and Bespoke Wallpaper Music. It is this ecological sensemaking that extends Kim’s sonic interventions into realms of material, psychic, and affective implications. Sound is emplaced in the thriving vitality of ecology—not just spoken of in relation to its technology or style or aesthetic or even art history, but through the ever-evolving history of sense and the sensible. This ecology is also structured by what French film theorist Michel Chion discusses as the “acousmatic,”6 or the experience of sound without knowing its sources. A vaster relational world is implied though this acousmatic intuition, precisely, an ecology that exists beyond the immediacy of the exhibition space.

This question of ecological sensemaking offers us a glimpse of the history of the sensible in the contexts that the artist works within: music (traditional music knowledge systems and instruments; the production and reception of pop music in Korea and their use in ideological contestations across the DMZ border); urban environments (various contexts of audition in urban spaces, such as announcements used in public infrastructures [transportation, telecommunications, mass media]); protests; memory work. Throughout the practice of the artist, sound is emplaced in wider ecologies and cultures. In the context of both works discussed above, sound is not just a mode of textuality meant to be read, listened to, and deciphered; it also embodies infrastructures of sensing, recognition, translation to value, and the concomitant questions of assemblies and circulations. These elements are addressed and sound as culture is mapped out and fleshed out as an ecology.

These scenographic and choreographic impulses converse with an archaeological sensibility as well. We see this in particular in looking at the ways in which sound and its history may be drawn out from traces of the material and technological kind or, via negativa, by way of symptomatic absences. The diegetic structures these impulses, especially in relation to how sensemaking is mediated by the ecological, as it alludes to how material realities, our perception of these, and the mediations of sound, coincide as an expansive experience. As Hven further explains: “Our perception of the diegesis can neither be understood exclusively on the basis of our perceptual system nor solely on the affordances of the mediated environment.”7

The archeological sensibility plays out exceptionally in A Story of Oseonbo: Sounds Lost in Translation (2022). For A Story of Oseonbo, Kim interrogates how cultures of making and sensing music had been transformed through the colonial encounter, particularly relating to different ways of mediating music into legible notation and what shifts and gets lost in translating between the vernacular and the universal. In thinking about how this change happens in the history of Korean traditional music, she looks at the history of Jeongganbo, “a flow-based score that indicates both pitch and note duration.” In an effort to “introduce traditional Korean music to the outside world or to incorporate foreign sensibilities into Korean musical compositions,” musical notation slowly started abandoning this vernacular notational language for a more rigid staff-based system used in Western classical music, which has been deemed universal since. This shifted not only how people systematize music learning, playing, and recording, it also delimited what tones can be heard and appreciated. The staff-based system is not able to convey the fluidity of the notation used for Korean traditional music.

A Story of Oseonbo focused on Joseon Guak Yeongsan Hoesang, a score transcribed in 1914 by Kim Insik, a teacher at the Joseon Court Music Study Institute, who translated the yanggeum (Korean dulcimer) score for the piece Yeongsan Hoesang into Western staff notation. The work presented a documentary film with interviews with traditional music performers, composers, and researchers, on the implications of moving away from more vernacular modes of musical notation. A Story of Oseonbo threads through material and knowledge cultures, tracing how practices of hearing and listening and sensemaking in general, are constituted through and transformed by the colonial encounter. The scenographic and choreographic, which are fleshed out in contemporary terms in Tripartite Confrontation and Bespoke Wallpaper Music, are complicated by this archaeology of sensemaking. Through this archaeological turn the history of the sensible is made to allude to cartographies of knowledge and politics, the very materials that shape the history of the sensible. By historicizing the sensible we also historicize with it the knowledge and political regimes that structure what is seen and heard. Furthermore, the more we know about the history of knowledge and politics in a certain milieu the more we know about the possible materialities of sensible forms.

This archaeological sense also opens another important question: What transpires when we interrogate the fixation and consolidation of regimes of knowledge around certain senses?

The seventeen-minute video Brilliant A (2022) offers an account of the arrival of the first piano in Daegu, South Korea, which was brought by an American missionary. The piano was used to introduce the Pitch A, the standard by which instruments are conventionally tuned. In Ear Training (2022), a fifteen-minute video, Kim considers the collision of aesthetic education with Japan’s colonial and military history in Korea. The work simulates pitch-perception exercises that were designed in Japan during the country’s occupation of South Korea: students and army officers were made to listen to the drone of army planes and asked to notate what sounds they heard. Both works denaturalize sensemaking by mapping its learning and adaptation within frameworks of coloniality and warfare, interrogating relational agencies around sound—sensing it, learning it, discoursing about it—politically, ethically, and pragmatically charged. The history of the sensible is also the politics of it.

The archaeological shapes Kim’s obsession over forms of mediating sound and music through the different ways to translate external phenomena and stimuli into choreographic annotations, from scores and notations to transcriptions and recording, even to the more film-adjacent trope of “treatments.”8 This is prominent in works such as The Units of the World According to ;Semicolon (2011), where accompanying a single-channel video are thirteen drawings—scores—relating to various punctuation marks. The Units of the World According to ;Semicolon is the third part of Lesson for a Naming Office: Three Treatments (2009–2011), a book and a video trilogy where the artist looks at the necessary and arbitrary connections between symbol and sound. She explains: “Through the recontextualization and rearrangement of such linguistic acts, the work reexamines the conditions that make speech and writing possible, inviting us to envision alternative ways these elements might interact.” The scenographic, choreographic, and archaeological perspective help us appreciate the richness of the history of sound and music as a history and politics of sound, precisely, an aesthetics of the sensible. Kim’s artistic practice acknowledges the poetic potency of sound at the same time as it calls out its construction and contingencies.

To Future Listeners fleshes out this archaeological impulse further. A wax cylinder recording is at the core of the first two iterations. In 1896, American anthropologist Alice Fletcher requested three Korean students who were then studying in Washington, D.C., to sing Love Song: Ar-ra-rang 1, what ended up as the first example in the history of Korean traditional music to be captured in a recording medium. Fletcher’s ethnographic project is an achievement of 19th century American anthropology wherein the phonograph allowed the music and language of indigenous populations to have extended and mediated afterlives exceeding their utterance or performance.

In To Future Listeners I (2022), Kim leans into the preciousness of the material technology itself. Exposed to its environment, wax cylinders degrade at an exponential rate. The wax surface onto which markings that translate to sound gradually smoothens and deteriorates whatever intentional inscription into illegible abrasions. Kim feeds this information into a noise reduction plugin seeking to salvage what marks remain legible as musical notation. In this process, the software, instead of distilling a cleaner sound, interprets the data in the smoothened wax matrix entirely as noise. The resulting work is an audiographic representation of this process as it transpired, dubbed with an excerpt by the seminal work of sound studies pioneer Jonathan Sterne, who wrote about the cultural histories of sound reproduction and media formats.9

In conversation with this digital intervention is an actual phonograph, produced in the 1900s, which comprises To Future Listeners II (2022). Kim recorded herself singing Love Song: Ar-ra-rang 1, using the original wax cylinder technology. The recording continuously plays the artist’s voice, playing out the gradual degradation of the encaustic material. The two works allude to the futurity not only of the phonographic technology itself but also of the anthropological frontier that this technology surmounted.

The ethnographic motivation is complicated in both works by an archaeology of material. The stability and permanence that constitute the imagination of the ethnographic recording are eroded by the technology that has enabled it. In this way, the archaeological impulse itself fleshes out relationalities of the scenographic and choreographic kind: the phonograph standing aloof in one corner of the exhibition space inspires awe and intimidation and the recursive and disembodied operations of the software casts a clinical eye on what is supposed to be the longue durée of ethnography’s disciplinary and ideological history. This is an achievement of Kim’s practice that extends to the new works she is presenting for this exhibition.

It is through the scenographic and choreographic that we see how sound becomes astutely material and political. As moments of ecological sensemaking, both tropes situate our engagement with sound within the fraught frameworks of the public, the political, and by extension, the democratic. What happens when we reconsider definitions and deployments of ideas of the public, the political, and the democratic, in relation to the more ambient and more dispersed, and therefore more precarious and precious, history of the sensible? What happens when we engage with speech and song as embodied and emplaced practices of navigating social space? In Kim’s work, sound is made, heard, historicized. Taking stock of its promise as a mode of ecological sensemaking, it is through sound that in Kim’s works contexts of sociality beyond the immediate present and through contemporary immediacies are made sensible.

I end my essay with one of the newly commissioned works for this current exhibition. In Go Back To Your (2025), we hear recordings of conversations that diasporic women hear in open public spaces. It is a soundscape of threats and slurs and we listen in as if we are hearing these alongside their victims. There is something about spoken harassment in the way that it is heard not only by its direct addressee but also by a couple of others who might have experienced their very own trauma from comparable circumstances, who might be more than used to internalizing such violence. Kim recreates these soundscapes, some shared with her and some she personally experienced. Within this history, Kim looks at how Korean-American women have developed their own system of deflecting harsh words and defending themselves against these aggravations, such as faking a cough to drown or mask these unpleasant interpolations. During the pandemic, however, this gesture became more fraught, especially with the global respiratory pandemic being coded as an Asian one. Instead of drowning verbal harassment, coughing all the more instigated untoward verbal confrontations.

Go Back To Your offers a different conceptualization of the public, democratic space constituted as a space of audition. Hearing and listening flesh out notions of the public and the democratic as much as speaking as a representational act. Hearing and listening reconsider questions of address, in the way audition is always already ecological—addressed to whoever listens or hears, constitutive of belonging that exceeds the immediacy and intimacy of the optic or the haptic. When audition becomes the site of belonging, its subjects are everyone who hears and listens. When audition becomes the site of violence, its victims are everyone who hears and listens. Within these parameters, Kim stages the scenography and choreography of the democratic as it is made material not by who recognizes its people or its symbols, but by who is interpolated by speech in this open-ended spatiotemporal situation.

In Kim’s work we are made keenly attentive to the aesthetic of the sensible, particularly the poetics and politics of audition. It is not only a history of music or song or speech that Kim is inviting us to reconsider or review in her works. In many ways, Kim’s works are also an invitation to rethink the very agency that we rely on when thinking about sonic and acoustic material. If we rethink this agency as ecological, we draw not only from orders of signification but also the coming together of “a felt, mediated environment” and “the spectator’s embodied organism.” Precisely, we see these convenings across different schemes and scales in Kim’s practice: archaic instrument playing deteriorating song; attempts to rehabilitate deteriorating song by way of contemporary software; bodies responding to cues by other unseen bodies; ears learning which musical note sounds like the drone of a war plane. This ecological agency alludes to a vaster world where sensing and sensemaking extends, rendering our immediate contemporary only an aspect of a continuing and contingent being-in-the-world. In all these, an ecological sensemaking orients us: locates us within these environments, allows us to mediate various vicissitudes, gives us our cues, tells us when it is time to listen, when it is time to move.