Kim Sangjin

Kim Sangjin has worked with various medium and forms to address the contemporary perspectives on the world and human beings as well as the changes they go through. He spotlights today’s contemporary art by making visual through his work the human experience of living with and questioning the absurdities in our present reality. he has held solo exhibitions at Alternative Space LOOP (2014) and Kumho Museum of Art (2013), and his works are housed in the Museum of Contemporary Art Busan and Arario Museum.

Interview

CV

Education

2013

MFA Fine Art, Goldsmiths, University of London, UK

2010

BFA, Sculpture, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea

Selected Solo Exhibitions

2021

In the Penal Colony, Wumin Art Center, Cheongju, Korea

2019

Crosscheck, osisun, Seoul, Korea

2016

control beyond control, out, sight, Seoul, Korea

2014

Phantom Sign, Alternative Space LOOP, Seoul, Korea

2013

Landscape: Chicken or Egg, Kumho Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

2011

Ingredients, Gallery Min, Seoul, Korea

Selected Group Exhibitions

2021

Sustainable Museum: Art and Environment, Museum of Contemporary Art Busan, Busan, Korea

2020

Sugar Cum Pro: White and Viscous Gold, OS, Seoul, Korea

Plicnik Space Initiative, D02.2, Online exhibition, UK

2019

Kumho Young Artist: The 69 Times of Sunrise, Kumho Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

2018

A-Mode, Yeji-dong, Seoul, Korea

APMAP 2018 jeju – volcanic island, OSULLOC Tea Museum, Jeju, Korea

2017

I, II, III, out, sight, Seoul, Korea

Korean Eye: Perceptual Trace, Saatchi Gallery, London, UK

Museum Zoo, Seoul National University Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

Landscape, Micro Museum, Seoul, Korea

2016

Uncertainty, Connection and Coexistence, Suwon Ipark Museum Of Art, Suwon, Korea

Jikji, The Golden Seed, Cheongju Art Center, Cheongju, Korea

The 4th Amado Annualnale, Amado Art Space, Seoul, Korea

2015

The Brilliant Art Project 3: Originability, Seoul Museum, Seoul

Rain Doesn’t Fall for Nothing, Creative Industries Centre, London, UK

Into Thin Air, Kumho Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

Robot Essay, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, Seoul, Korea

Un Certain Regard, Kumho Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

2014

Duft der Zeit, Kumho Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

Dreaming Machines, National Centre for Contemporary Arts, Moscow, Russia

2013

London Art Fair 2013: Location of Reality, Hanmi Gallery, London, UK

2012

Phobia, Hanmi Gallery, London, UK

Situated Senses 02: 30cm of Obscurity, The Old Police Station, London, UK

2010

Instant, Unknown, Uncontrolled, Unacclaimed, Kosa Space, Seoul, Korea

2009

Sulwha Culture Exhibition, KoreaING, Seoul, Korea

2007

Hello, Chelsea! 2007, PS 35 Gallery, New York, USA

Selected Awards

2020

Wumin Art Prize, Wumin Art Center, Cheongju, Korea

2016

SeMA Emerging Artists, Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

2013

Alternative Space LOOP, Seoul, Korea

Kumho Young Artist, Kumho Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

2007

70 Young Emerging Artists, PS 35 Gallery, New York, USA

Selected Residencies

2013

Kumho Art Studio, 9th Resident Artist, Kumho Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

Selected Collections

Kumho Museum of Art

Museum of Contemporary Art Busan

Arario Museum

Critic 1

On the boundary between belief and doubt

Kim Younok (Curator, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea)

Kim Sangjin’s work begins from his doubt of the human cognitive system generally believed to be absolute. A proposition that serves as a basis in the artist’s oeuvre is that people’s value systems for what they consider to be fixed, such as languages and symbols, time and space, and institutions and laws, are incomplete and in fact, the results of a societal agreement. The artist’s interest in such extensive systems (language, institutions, laws, etc.) and their incompleteness (or dark underbelly) arises from a gap in our human cognitive process grasping between our perception of whole and parts.

The artist gives shape to such concepts through sound installations and sculptures using an array of everyday materials. His installation works incorporate mechanical devices accompanied by distinctive sound and movement, such as in the In Visibility series (2013) that utilize printers to print ink on surfaces of water or Meditation (2013) that presents a speaker to play a pre-recorded sound of a moktak alongside the actual Buddhist wooden percussion instrument. The Three Little Pigs! (2014) employs animal sounds alongside wooden crates, and Icarus stuffed birds (2013) places a speaker to play bird songs inside a birdcage suspended in midair by helium balloons. These works portray the fallibility of perception while also recounting the breakdown and reproduction of the original’s symbols (language). The artist regards this “simulation”—that is, reproduction in the form of “pretense”—as one of the distinguishing features of our time in constructing reality. Decaffeinated coffee retaining the taste of coffee, mint-flavored candy not containing actual mint, and active noise control systems that block noise with noise all reveal the prevailing contemporary method of reproducing or replacing the original symbolically.

Kim’s early work Air purifier (2011) best summarizes the gap between linguistic value and our perceptions, presenting an air purifier and flower in a glass case. There, the machine, misidentifying the flower’s scent as odor, runs until the flower finally withers. The work thus sheds light on an incongruity produced when the linguistic values of “scent” and “stench” are coupled with a mechanical sensor built to imitate the human olfactory system. As such, the artist speaks about certain points of irrationality and ambiguity in respect to the audience’s various emotions (curiosity, guilt, etc.) produced by a staged situation and the uncertainty it poses.

Recently, Kim Sangjin has moved beyond his interest in human cognition, extensive systems, and their incompleteness (or dark underbelly) to present works on today’s reality and future, repeatedly deviating from and supplanting any original intentions. The artist’s recent work Fuck you, and I will see you tomorrow (2020) is comprised of a large dining table set in a purple-hued room with multiple displays fixed on the ceiling showing a sky overcast with storm clouds. On the table are five smartphones, each device laughing and chatting away. It is a web- and digital-based tech utopia, which the artist presents along with its new possibilities and prospects, the resulting emptiness and anxiety that coexist in our reality and our future.

Here is an artist who says, “The expectation that every problem can be solved since anything has become possible, and the fear that everything can be miserable for that same reason are simply the two faces of a future where all is void for everything has been (ful)filled.” Kim thus prods us to question both our absurd reality that faces a virtual world and a world of networks picking up speed since the pandemic and our future as a double-edged sword. And, as such, Kim continues to build upon his oeuvre of fifteen years that uniquely combines various mediums including sound, kinetic installations, and new media, inviting us to examine our own cognition and values in which we believe unquestioningly.

Critic 2

We Will Disappear

Lim Jinho (Director, out_sight)

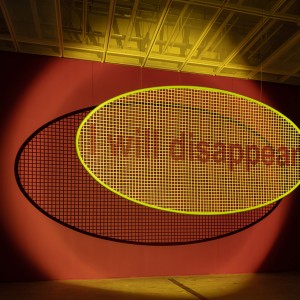

So goes the red text on the grid hanging in midair:

“I will disappear.”

And as the red-lettered text “disappears” fulfills its duty as a prophecy or referent by disappearing from the shadows of the wire mesh (#I will disappear#, 2021).1 But it is a matter of fact that language alone cannot speak for itself. This scene where language speaks on its own reveals the missing voice—the agent (human)—and altogether erases the narrative of representation. And the explicit, self-referential cycle revealed in this work certainly seems to portend a situation that is to come.

On the square lawn beyond the glass window stands a yellow sign that reads “wet floor” (#Oasis#, 2021). Submerged in a glass water tank filled to the brim, the sign remains wet inside the sealed tank, rain or shine. The audience acknowledges the sign from a dry spot indoors, where the rain can never reach. In this sense, the warning “wet floor” applies singularly to the warner—the sign itself—and neutralizes the general narrative structure of the sign. This sign, trapped in an internal cycle, appears to block out the viewer, the agent of language. Thus it is the humans, once again, who “disappear” in this space.

Taking a second look around the exhibition, viewers will notice the prevalence of signs, namely, signs of disappearance. Examples include people half-gone, permeating into protective colors, or entirely gone save for the remaining eyeballs. Everything about this space flushed with light, depth, and color screams of disappearance. Many of the expressions of disappearance found in the exhibition space borrow from the form of memes2 and are straightforward in their delivery, which viewers can grasp intuitively. However, for a deeper understanding, it is necessary to understand something of the process behind Kim Sangjin’s past works and how he has reached today’s theme of “disappearance,” the theme piercing through the entirety of his artistic practice.

Among his early works, the project that most details Kim Sangjin’s question about language is #Dog sounds# (2010). The work involves 48 speakers attached to a metal drum container, playing the sounds of barking dogs in 40 different languages. Heterogeneous onomatopoeia such as “mung mung,” “bow-wow,” “kong kong,” and “blaf blaf” come together and collide in a cacophony of strange barking sounds that dismantles the functions of these collected signifiers while simultaneously creating yet another signifier to the original form a dog makes naturally, not present anywhere in the work. The validity of this question is established by the fact that the onomatopoeia closely resembles a direct depiction of reality, deviating from the dogmatic relationship3 of the signifier and the signified. In a 2013 interview, the artist described this project as an audible forensic sketch montaged to catch the perpetrator (dog sound) who has disappeared.4

It goes without saying that the new sound resulting from the collision of different sounds is not the archetype of the original dog sound. In its place remains the void of the archetype (the referent of signifiers). In this regard, Kim Sangjin revealed that, from the beginning, the purpose of the piece was to collide these dog sounds. Since language itself is a source of involuntary loss,5 we have no choice but to lose the original referent when we start using language. And what is lost cannot be recovered. Interestingly enough, similar to how Immanuel Kant declared impossible the cognizance of a noumenon beyond our five senses, Kim Sangjin has also been denying the possibility of retrieving what is lost. However, the artist has persistently traced the remnants of what disappears behind language as if he were an amnesiac trying to retrieve himself.

Language6 has always functioned as the ultimate medium. It doesn’t speak for itself but only allows the mediators of language to speak. While coercive powers may cunningly abuse language, that doesn’t change that language itself stands as a fair and impartial mediator. This is especially true when it assumes the form of numbers.7 In this manner, language may belong to humans but seems to rest on a different plane from the impulsive, ambiguous, or uncertain nature of humans, acting as a rational mediator in human-to-human and human-to-external-world interactions. Moreover, we oftentimes equate ourselves with language. We speak, think, and understand the world through language, all the while forgetting its existence. At the same time, amidst a continuous torrent of language, we also experience ourselves fading.

Even when we experience something that transcends language and feel an urge far removed from its form, we have no choice but to express ourselves with language and face its sovereignty over our own limitations. As such, we are bound by our dependence on language. Consequently, through numerous experiences that teach us so, we come to realize that even if it may not deliver the whole truth, language is still the only world we can grasp. Ultimately, we exist in the middle stratum of a language network, one that connects what is internal with the external.

So what exactly disappeared from this giant prison of language? As dictated by Jean Baudrillard,8 “By naming and conceptualizing things, human beings call them into existence and at the same time hasten their doom, subtly detaching them from their brute reality”; when language points to the referent, the referent disappears behind language. Jacques Lacan described this structure through, firstly, an a priori world of language (the Symbolic Order) to structure the self—from the creation of self to one’s subconscious—and its external world into linguistic symbols, and secondly, the true form of the archetype (the Real) to disappear behind language. The place where these two orders are constantly at odds with each other, which exists only in a person and is separate from the outside world, is where Lacan saw the human self to be born. This is captured as follows in #Walks# (2017), a text-based work in which he describes the process of verbal reduction and loss by reminiscing upon personal experiences and the concept of “love.”

“Love is an ancient (one cannot possibly gauge how old), imaginary creature that is gargantuan in size. It is a rabid monster of excuses and rationalizations that swallows everything in sight, something only seen in an index much lacking in substance. … No, when I think about it, I resisted quite a bit for a young fellow. It was limper than I had imagined, swept up so easily by the heat of the moment, and standing erect in ire; naked emotions impossible to be named. Soon enough, someone (most likely through love songs) told me these feelings were love. As I hurriedly saved them by stuffing them into a storage unit, I lost its map promptly. In other words, all that I retain from that experience comes from the moment of locking that storage unit, this split second of tragic regret.”

Thus language is a tool of segmentation that simultaneously clarifies and reduces everything to a specific image. Doing so, language segments the referent from the mass of totality and ultimately displays it within an empire (reality) of images (simulacra). The faith in Western traditions—namely language (sign)—has accelerated since modernity. This blind faith augmented reality by surrendering attempts to obtain compensation for language’s imperfections from a world outside of language and instead choosing to cover up its shortcomings with an endless torrent of language instead. This surrender of the archetype evolves into faith in language, which in turn evolves into an oblivion of the world outside of language. In the end, oblivion expands and circulates into dependence upon and drives to complete a linguistic world. Segmenting the lumps (totalities) and arranging them as homogeneous particles; reconstructing the disconnected into connectable modules; placing the connected modules in the symbolic chain of flow: this is how language, constantly renewing the realities of symbiosis (language–human), made the world of archetypes disappear.

However, here rises a critical paradox. If the real world is what has disappeared as a result of humans projecting the order of language onto a world outside of the human, this means humans, too, cannot avoid disappearing, for, in this age and era, the linguistic definition and images that define humans seem more entrenched than ever. But this disappearance of the human is not on the same level as a simple event whereby one vanishes after a speech. It is complex at the level of the body (the real), self (the imaginary), and language (the symbolic), and the artist has, in his past works,9 continuously traced this aspect of the void in numerous contexts and subject matters. Even in this exhibition, the disappearing humans showcased by the artist share the prerequisite of “the disappearance of the human in contemporary situations where the virtual precedes reality.” At the same time, they implement disappearances on different levels.10(It should be noted, however, that they all disappear within a self-referential structure.)

The first disappearance is the human body. In #Chroma Key Green# (2021), a green figure sits in a transparent punching bag that hangs before a green background, staring at its viewers. Here lies the first element of a paradoxical structure: the color green. As expressed by Kim Sangjin in his text-based work, #Crosscheck# (2019),11 modern humans have escaped from the totality of nature and proceeded to diminish its mystique with the structures of language (concrete, measurements, surveying, biological research, climatology, capitalism, etc.). However, because humans live in bodies that are part of nature, they are inevitably nostalgic about nature they themselves have removed. Thus, in modern visual signs, the color green is the quintessential symbol for mankind’s wish to return to nature (think of the names “green growth,” “green belt,” “Green Party”). Nevertheless, the “chroma key green” here happens to be the most artificial of greens, a color that exists to erase reality during the process of media production. If green, the color that of nature, stood for a longing for the past, the green of a new era, one that caters to the narrative (media), looks to the future. This is why the human body in the chroma key suit becomes all the more meaningful. In this paradox of green that spans—from the past to the future and from nature to artificiality—the far ends of the spectrum, this chroma key figure that exists to disappear is the sole body that retains its full physical form in an exhibition filled with disappearances.

As the saying goes, “Anatomy is destiny.” Humans are double-bound by a structure that locks our bodies in a grid of language and our minds in the prison of the body. As such, we are destined to exist in conflict. In the past, there were traditions of sensing, exploring, and respecting the body as a basis for the existence of spiritual entities and acts of moving towards finding the self, beyond-self, or losing the self to reach transcendence and discovering meaning or liberation (most of these traditions stem from outside the Western rationalist framework, such as animism, Taoism, or the physical practice of yoga). However, contrary to traditional or historical views on the matter, we see the body today as an object for diagnosis, treatment, and renovation under the guidance of postmodern scientism. Psychologists of the modern era have discovered the unconscious as an entity of the body that exists beyond language, although the unconscious also soon disappeared as another subject for analysis and treatment to improve linguistic consciousness.12 Thus, the body metamorphosed into a well-tamed, self-supporting device, disappearing under the shadows of meticulous analysis of excessive language.

Consequently, we are now able to say, “It doesn’t matter. It is only the body, and it will soon be over!”13 In this analytical view of the physical, the body becomes thoroughly and exhaustively signified. Drugs penetrate the body, the Real that is absolute, and rearrange it within a network of signs of the medical and pharmaceutical industry. In this manner, the body’s supposedly forgotten senses appear more apparent than ever as a symbol that rests above the reality of language. Thanks to the electron microscope, the body is now informatized down to its virtually smallest microscopic particles (DNA). As Donna Jeanne Haraway predicted in #A Cyborg Manifesto#, are we not of bodies that are interchangeable with and, as a result, disappearing into numerical values? This contemporary context of the body uncannily overlaps with the one in the chroma key suit.

Here we make an important discovery of a broader possibility. In the past, the only way we could or yearned (Thanatos) to return to our original body of existence —the nature of Eden—was to escape the reality of language (death) altogether. Nowadays, we dream of a possibility to disappear into a linguistic reality (hyperreality)—a new kind of nature—by completely conquering the body through technological means.14

But the body in the green suit is forever trapped in a plastic punching bag, unable to enter the utopia of extinction. In this mechanism of simulation that exists for transparency, the body dons the mantle of disappearance. But by sitting within a transparent structure of constraint, the body puts itself in a contradictory situation, where it cannot disappear or be obscured. Consequently, the mid-level transparency evident in this work enters a cycle of self-referential structure by simultaneously presenting and omitting the body in endless repetition. So there lies the helpless body, unable to disappear or exist.

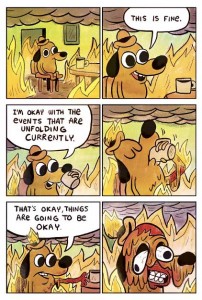

Of course, in reality, we may not be that interested in the disappearance of humans. If so, the scene opposite—where eyeballs uncannily roll inside a smartwatch saying, “This is (unexpectedly) fine”—may not seem like much of a paradox (#This is fine#, 2021). The work, named for a meme of a dog15 sitting in a burning room while sipping a cup of coffee declaring, “This is fine,” is reminiscent of us following COVID-19, hit by the disastrous event of losing our then reality. The void revealed by bodiless gazes, staring at each other from a transparent table and stand, is dramatically at odds with the famous performance16 by Marina Abramović. Should #Chroma Key Green# present a body unable to either disappear or exist, #This is fine# offers a body and reality already disappeared, predicting for us a daily life of emotionless void, where we can neither have high hopes for the future nor feel the tragedies of disaster.

At the center of the exhibition space, we see bodies half-gone (#Lo-fi Manifesto_Cloud Flex#, 2021). The ceiling display plays a video of colorful, hypnotic flashing graphic patterns on repeat; as the students are sucked into its vortex, left below are neatly lined empty desks and chairs. Unlike other works in the exhibition that, with their paradoxical nature, manifest pessimism or hollow contemplations, this huge installation has a simple structure that gives us hope for the future. At first glance, the work is reminiscent of the Pink Floyd album #The Wall# (1979), but it’s hard to detect any hint of oppression and resistance on this stage, from which even the teacher by the podium has disappeared. The space resonates a dreamy, electronic music that is fitting with the mood of the piece, heightening anticipation. Does this mean there’s a bright future ahead of us? Franco “Bifo” Berardi argues that the future is gone.17 This is because the idea of a predictable tomorrow no longer entails a future where possibilities and uncertainties coexist, but is now a mere extension of the disastrous realities of today, and the overstructuring of reality will remove doubt and uncertainties that are considered human by the future and mankind.

However, the future is a fast-approaching reality, and we are forever sandwiched in the gap between present and future. Just as the reality of the modern age centered on divine order meeting its end, today’s reality is disappearing. (Keep in mind those moderns who, at the heart of change, shouted that the end was nigh as God was disappearing.) As delineated by Hannah Arendt, the scientific and technological revolution collapsed the perceptions of a feudal system.18 Similarly, today’s disappearance is driven by a new Archimedean point called the meta. The structure of the meta is far from new. It is a self-referential structure that moves one’s perspective to the outside of the level of “absolute reality”—namely, the existence of the subject—and objectifies the situation the subject is placed in as “part of the choice.”19 Don’t humans do their share of slaughtering subjects of the divine order using scientific metrics as their basis?

As Jean Baudrillard mentioned in #Simulacra and Simulation#, in the era of God, it was God in all His mighty power who warranted all existing signs. Following the death of God, however, the reality of simulation constructed a huge empirical world by harnessing the power of numbers (science, technology, economy, capital). This readily replaced the aura of reality by presenting both the mighty human and his trusted friend-and-guarantor, numbers, to the “void” hidden behind the signs and symbols of reality. Nevertheless, as the artist details in his text-based work, #Crosscheck# (2019), modern dynamics were convinced that numbers—which erased God—would create a utopia the almighty mankind dreamed of, paradoxically leading to today’s reality where humans are swallowed in a simulation of numbers. 20

Hitherto, we observed a world of new possibilities in the meta structure created by the disappearance of the body. Now we are aware that “the world of simulations as a stand-in for reality” is not the only card in our deck. When the meta of reality is realized, the aura of reality disappears (while meta speaks of a state of transcendence, it coincidentally means “death” in Hebrew). All that remains is the choice, and the choice boils down to a question of whether to “supply electricity to the lamp in real life” or “supply electricity to the lamp in the game.” The situation of choice is now our absolute reality.

Behold the Messiah as he fast approaches, steadily pitter-pattering upon that infinite grid yet never quite arriving (#Messiah is coming#, 2021). The incompetent savior is doomed to walk forever, trapped in a meme of infinite repetition, suggesting that utopia may not arrive after all. But what of it? Just as hell does not exist without heaven, dystopia cannot arrive without utopia. The vague expectations of the future suggested by Kim Sangjin in #Lo-fi Manifesto_Cloud Flex# are no antiquated hope that glorifies the traditional utopia as a reward for almighty humans who have replaced God. The excitement stems from an instinctive curiosity about an entirely new hierarchy sure to come with a new era of humans. 21

Now, let us return to the red text that dictates, “I will disappear.” This language, speaking the truth by fulfilling its own prophecy, is a great God of Silence. It spoke for and by itself even before we were born, weaving a reality of language and thrusting us upon its large fenced boundaries as if to herd sheep, entrapping us so that we might exist (or speak) only within its realms. This transparent voice—which has not once revealed itself since it gained life from humans—encouraged and urged us to make endless noise, and the voice grew on its own initiative. Consequently, it handed us the Lance of Longinus (numbers), instigated the death of our Father (God), and now reigns as the almighty ruler of the world, coveting its mother (body). The descendants of these shadowless ghosts are about to be born. The future, most likely, will resume from there.

1 The artist conceived the work after coming across a meme of a tennis racket (Figure 1), whose logo disappeared from its own shadow. The work is also in continuation of #We are not# (2017), a video installation showing security footage of an exploding rocket. Even as the ground churns and quakes, its anthropomorphized subtitles remain motionless, revealing the layers in language. The source of Figure 1 is as follows: https://www.reddit.com/r/memes/comments/8kqyzu/where_is_w/.

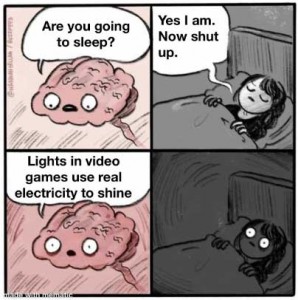

2 According to the artist, the exhibition title “#Lamps in video games use real electricity#” is borrowed from a meme born from a post on an American website, Reddit (Figure 2). Additionally, his works #This is fine# (Figure 3), #I will disappear#, and #Oasis# (Figure 4) were also conceived from memes. The source of Figure 2, Figure 3, and Figure 4 are as follows: “Are You Going to Sleep? is an exploitable webcomic made by Hanna Hillam. The webcomic which was introduced in June 2017 became an exploitable in 2018,” article from #Know Your Meme#, https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/are-you-going-to-sleep. KC Green,#This Is Fine#, 2013, https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/people/kc-green. The original entry is #SpongeBob SquarePants#, https://knowyourmeme.com/photos/1421465-spongebob-squarepants.

3 The linguistic theory of Ferdinand de Saussure presupposes that there is no natural or inevitable relationship between the signifier and the signified.

4 Kim Sangjin explains the work by citing a phrase from Umberto Eco’s novel #The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana#, where the protagonist hears something shocking and utters, “Where had I read that sound? Or perhaps it was the only one I had not read, but heard?”

5 “Involuntary loss” speaks of what is lost without realizing or noticing its absence.

6 In this essay, the word “language” forgoes its common definition but is employed to encompass all recognizable signs, including the number system and signals perceived by sensory organs such as sight, hearing, touch, and smell.

7 In his text #Landscape: Chicken or Egg#, Kim Sangjin describes the nature of language as follows: “Language is inherently assumed to be an equivalent system of signs. Thus, there shouldn’t be involuntary loss other than the ones triggered by the act of transferring the original non-language to language. (Though in reality, many errors and involuntary losses occur). In this manner, it can also be said that what is digital is a linguistic (symbol-systematic) fixation phenomenon of a more advanced reality. People seem to put blind faith in the objectivity of machine language and its recreations as langue that exists without #parole#. Alternatively speaking, machine language becomes a medium that hides its existence in sporadic transparency. This transparency is a privilege awarded to the most steadfast and universal religion and worldview of the times.” http://www.domadome.net/domadome/text_1/chickenoregg.html.

8 Jean Baudrillard, #Why Hasn’t Everything Already Disappeared?#, Trans. Ha Tae-hwan (Seoul: Minumsa, 2012), 17.

9 The following are Kim Sangjin’s works that explore the human body, agent, and the linguistic void: #Human copyright information# (2007), #The street where I’m living# (2010), #An approximate value# (2014), #Mars Spiritual# (2015), #In Visibility_refugee# (2015), #Jack# (2017), #We are not #(2017), #I know this steak is not real# (2020), #Fuck you and I will see you tomorrow# (2020).

10 These different contexts require an understanding of how each disappearance occurs relative to the others. This is because it is impossible to paint a void within a void, much as it is impossible to tell by a picture of the sun hanging at the horizon if it is a sunset or sunrise.

11 “Nowadays, the most important thing to consider when desiring something (or perhaps, what we should be desiring) has become the possibility of its mathematical (economic or scientific) restoration, and therefore, uncertainties have become things not desired or needed. Even when I rack my brain for something left in this world that defies such an equation, there is no denying that even the endless sea, lofty sky, winding sierras, and unrelenting rivers are but resources we can measure, process, and trade off. Nature exists as a resource for development, or at times environmental conservation (though even this is ultimately for the good of mankind). Of course, this does not apply only to nature.” Excerpt from #Crosscheck# (2019), a work of text by Kim Sangjin.

12 “We may say the same of the Unconscious and its discovery by Freud. It is when a thing is beginning to disappear that the concept appears,” from Jean Baudrillard, #Why Hasn’t Everything Already Disappeared?#, trans. Ha Tae-hwan (Seoul: Minumsa, 2012), 17.

13 During a lecture on #Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto#—a work that considers the dualism of digital virtuality and the physical reality—author Legacy Russell uses this line lifted from James Baldwin’s novel #Giovanni’s Room# to present the possibility of a cosmic being that transcends the limitations of the body.

14 “Tools have become more than tools to us. They are now nature. We are born in numbers and die surrounded by numbers. Thus, numbers will be our next nature.” Excerpt from #Crosscheck# (2019), a work of text by Kim Sangjin.

15 Refer to Figure 3.

16 #Marina Abramović: The Artist Is Present# (2010).

17 Franco “Bifo” Berardi, #Futurability: The Age of Impotence and the Horizon of Possibility# (London; Brooklyn: Verso, 2017).

18 Hannah Arendt, #The Human Condition#, trans. Jin-woo Lee (Paju: Hangilsa, 2019).

19 The self-referential structure objectifies itself, abolishing the aura that exists above it. Now is an era when even mythical values are rendered into symbolic capital, an age when we ourselves are reduced to an economic resource, developing, investing, and operating as mere components of an economy.

20 “The naïveté of modernity’s yearnings—towards a belief that this world of tools (the world of numbers) would faithfully serve their uncertainties (traditional beliefs, emotions, and other belief systems customary of the almighty humans)—couldn’t possibly have predicted the realities of today, where all uncertainties deemed irreducible are reduced to tools for the sake of tools.” Excerpt from Kim Sangjin’s text-based work #Crosscheck# (2019).

21 “In this space, even utopia and dystopia are but retro symbols floating about in thin air (or they will be used to mock old-fashioned idealists). Therefore, we should put aside for now any antiquated, crumbling emotions of excess fear and joy regarding the future. It’s time for the new race of humans to brace itself for a new era created by the quagmire of collapsed symbols.” Excerpt from Kim Sangjin’s text-based work #Sugar Cum Pro# (2020).

Critic 3

Objects in the mirror are closer than they appear

Mun Hye Jin (art critic)

In the beginning was the Word. It was only afterwards that the Silence came.

The end itself has disappeared…1

1. I grappled with how to approach Kim Sangjin’s work because polar opposite attitudes clashed throughout his work yet made a discordant coexistence. I spent quite a long time thinking about what it was that was out of joint, what I had almost understood but ultimately let slip between my fingers. Was it because Kim Sangjin’s work is difficult? No. Kim Sangjin explicitly reveals comparatively conceptual materials (language, sign, conventional wisdom, standards, etc.) in a straightforward way for the work’s final form, leaving less room for contextual vagueness or obscure intentions. Rather than dodging the questions raised, he tends to confront them head-on. Then the question lies not in the work itself but in the relation between the work and its intentions. The seemingly clear-cut and straightforward work, presented in the form of an object without further explanation, clashes with its intentions formulated out of a complex and lengthy thought process. I am thus left unsettled between taking the work at face value and focusing on its inherent thought process and relevant discourse. Such an issue stems from the fact that all of Kim Sangjin’s works are, in part, conceptual art. They begin by questioning how the world and system ought to be along with the consequential absurdities born there. He has consistently approached the imperfection of our inconsistent perception and the errors in our manmade rules and systems through the domain of signs and senses. Extracting audio from a sound source, employing artificial vocal programs, and devising a printer that can print on water, the artist’s works, which heavily incorporate technological apparatuses, are often labeled media art. In theory, the interpretation of a work remains an open-ended question. Thus there is no need to reject such a categorization. In fact, used as a medium of perception, the apparatus bears significance in Kim Sangjin’s work. However, his works focus not on the apparatus itself or its produced effects, but rather on such aspects as the existential conditions of a human being, the difference between reality and illusion in our technological environment, the deconstruction of our contemporaneous time and space, and the change in our perceptions. This leads us to question: What am I looking at? What am I who am looking at the object? And what are the systems and structures that intervene in my vision and cognition? In this regard, my own perplexity may be substituted with the question generally raised in conceptual art: the dilemma between the concept of the work that reigns more important than its material substance or visual appearance and the non-linguistic medium and sensory attributes that undeniably deliver the very concept itself.

The bottom line is that I think that obscurity or complexity sets Kim Sangjin apart and fundamentally aligns with the artist’s repeated questions about our perception and reality. The tension between physical substance and conception can be said to parallel the gap between object and text, as with the conflict between the world in front of our eyes and the signs of its referents. Furthermore, since the expanded interest in our contemporaneous digital environment in 2019, the artist has been dealing with more-extensive complexities of the absurdity. Reflected in the artist’s contradictory ambivalence, crisscrossing modern thinking and postmodern mindlessness, is the issue of contemporaneity intertwined with the premodern, modern, and contemporary. This essay attempts to sketch out how the works presented in Korea Artist Prize 2021 reveal the diverse manifestations of the absurdity without being too serious.

2. Lo-fi Manifesto_Cloud Flex (2021), stimulating our sight and hearing with a repetitive rhythm reminiscent of 1980s synth-pop, is both visually and conceptually the exhibition’s centerpiece. Against the slow but hypnotizing music continually playing in the background, the viewers are drawn to look at an immense screen, composed of 20 individual screens, showing colorful patterns in repeated motion. The dazzling patterns stop our thinking and draw us to our senses. The delusion of our visual perception sucks us into the ever-repeating screen. Our minds sink into it while our bodies remain behind. Having soared over their desks to plunge into the screen, the students, or their lower bodies left dangling, become a portrait of and simile for today’s people drowning in the flux of images projected from the black screen. While our flesh exists in meatspace, our minds are confined in the virtual space of the screen. Although most of our life takes place in YouTube videos, games, and social media, the physical limitations of our body existing in the form of a biological being nevertheless constantly pull us back to our physical body formed of “flesh.” Such division, created by alternating back and forth between the virtual and the real, is the contemporary contradiction visualized in Lo-fi Manifesto_Cloud Flex. The artist states the theme of this work to be not the hi-fi virtual world pursued with great expectations by those of modernity but the lo-fi virtual world that has become our everyday reality. Current changes indicate the end of materiality-based traditional humanism, yet also signify the arrival of a new kind of human being and world based on the novel experiences of virtuality.2 The artist’s lo-fi virtual world neither clearly differentiates the virtual from the real nor substitutes one for the other. Instead, it appears to be a place where both worlds absurdly coexist.

The future has arrived, but we are still in an unresolved state of uncertainty as to where we are moving toward. This is the root of contemporary anxiety and the point that brings about a sense of déjà vu. It is unnecessary to extend the scope to philosophy to find déjà vu to be the driving force behind Lo-fi Manifesto_Cloud Flex. In keeping with the synth-pop aesthetic, Lo-fi Manifesto_Cloud Flex comes across as retro in concept and form. Primarily, symptoms of fragmentation directly relate to a postmodern delirium, which Jean Baudrillard and Fredric Jameson put forth. In a world absent of all referents and left rotating with nothing but simulacra, there remains uncanny schizophrenic happiness, devoid of any sense of depth or distance, leaving only an intensified present. What Jameson describes as “suddenly engulf[ing] the subject with indescribable vividness, a materiality of perception properly overwhelming”3 can be applied to Lo-fi Manifesto_Cloud Flex without much difficulty. Considering not production, but post-production, which reassembles rather than creates, the technological format that defines our contemporary digital environment, the retro-ness of Lo-fi Manifesto_Cloud Flex in itself is contemporary. However, repetition always yields difference. While Jameson described the intense excitement and hallucination of dismantling the signifying chain and liberating signifiers as the hysterical sublime, the glaring optical illusion visualized by Kim Sangjin comes closer to the exhaustion described by Franco “Bifo” Berardi. The “semiocapitalist acceleration” and the “overexploitation of nervous energies” make threshold values unresponsive to any stimulus.4 Of importance here is the state of repeating rather than clarifying contents. The temporality of repetition, continually circulating and nullifying the linear flow of time, is the contemporary time of semiocapitalism, one separate from the noumenon.

Lo-fi Manifesto_Cloud Flex can be associated by form with op art. While this association is coincidental, especially considering that Kim Sangjin’s previous works were far from visual spectacles, the analogy is worth considering. Lo-fi Manifesto_Cloud Flex resonates with op art so that eye and body correspond. Despite its pure visual properties, its optical illusion patterns cause such physical effects as dizziness, headache, and vertigo. The inherent duplicity of visual tactility was employed to criticize pure visuality from the standpoint of anti-art (Marcel Duchamp’s Rotorelief No. 6: Escargot, 1935) and made way for the art critic Rosalind E. Krauss to examine op art as an example of a “new perceptual abstraction” responding to the era of electronic media.5 Intertwining eye and body, Lo-fi Manifesto_Cloud Flex points to our mediated senses, a property of contemporary synesthesia. At the same time, the work reveals the inevitable coexistence of reality and virtuality caused by the inability to separate mind from body. Virtual reality, touted as the most realistic tactile epiphany, is, in fact, a false sense of vision mediated by a headset as its apparatus. The epiphany of tactility via sight is tangent to the body’s disappearing by being sucked into the delusional patterns. However, parts of the body not engulfed but left behind appear to expose the duality of contemporary there-being that crisscrosses the real and virtual worlds. And although the virtual world is given more weight as reality dwindles, the presence of physical existence exemplified by the fatigue of online lectures has, ironically, become even more underscored.

3. Chroma Key Green (2021) and This is fine (2021) explicitly portray the contemporary digital environment, where the artificial has become the new nature and the human condition that simultaneously exists and does not exist. Today’s data matrix, in which tools are “no longer tools but have become nature (quoted from the artist),” is most directly stated in Chroma Key Green. Conventionally, the color green has symbolized intact nature as well as its intrinsic materiality. However, in our contemporary moving image production environment, where postproduction is essential, green is employed to erase such materiality. In this sense, the figure wearing a green chroma key bodysuit simultaneously embodies the real and unreal and serves as a metaphor for existence of contemporary human being.6 One interesting paradox in connecting concept and form occurs here: finding the expression of an image world, where physical properties disappear, even more limited by such physical properties. To render realistically a human being crouching in a transparent urethane vinyl bag, the artist looked to traditional carving techniques of sculpting materials from the outside along with 3D-printing techniques of building a figure from within. Since the massive sculpture had to hang from the ceiling, its physical properties inevitably became core to the overall working process, implying the relationship between the virtual world and the real world we cannot entirely escape, no matter how extensively numbers are substituted for the real world. In fact, Chroma Key Green combines two contradicting styles of previous works. At one end are works using traditional sculpting methods exemplified by Human copyright information (2007), which presents a sculpture as a replica of the artist carrying a bag containing another simulacrum, and The street where I’m living (2010), which experiments with the minimum condition of recognizing the noumenon by installing in the streets a sculpture that replicates the artist. And at the other are works realizing today’s electronic nature in which simulacra substitute for reality, such as I know this steak is not real (2020), depicting humans revolving in a world of crumbled hierarchical structures as drifting signifiers, and Electric Cave (2018) replacing the sound from an actual cave with an ASMR sound file to help us sleep. Kim Sangjin once mentioned in a text a slippery, sticky, and slimy subversive possibility of viscosity exuding out of an obsessive matrix of a world of tools.7 He most likely meant to discuss the general possibility of violation that may contaminate a data society based on consistent forecasts. However, the inerasable organicness of our age-old flesh may also pose as an impediment that paralyzes “Signifiers–the carcass of dead meanings (quoted from the artist).”

While Chroma Key Green deals with discordant symbiosis of the real, organic world and the abstract world of signifiers, This is fine focuses on the present landscape overpowered by simulacra. The eyes displayed on smartwatches, engaged in a staring contest, remind us of the predominance of virtual persona whose social media accounts replace physical beings in meatspace. This is fine presents a slightly different attitude from Chroma Key Green. While the latter offers a relatively serious existential deliberation despite its self-mockery and sardonic humor, the tone of the former is much more cynical, negligent, and dry. This sentiment is shared by the meme after which the work was titled. Sipping a cup of coffee in a burning house, a character uttering “This is fine” refers to the state in which we live disconnected from reality, immersed in a virtual world, or to the social atmosphere geared toward pursuing some insignificant but definite source of happiness detached from whatever going on in the rest of the world. In a world that consists only of an endless chain of slippery signifiers that deny any guarantee of standards or orders, who cares whether the steak is real? And does that even matter? After all, there are smartphone-mouths, devoid of physical flesh, engaged in lively conversation at a dinner table (Fuck you and I will see you tomorrow, 2020).

In connection, Kim Sangjin’s attitude toward memes requires attention. He once stated that memes, images that many people online enjoy as satirical amusements, had inspired him in many ways with their treatment of the absurdities.8 They are hidden plays for only those who know of their context, profane in the way that they disrupt and challenge rank and hierarchy. They are difficult to predict, mixing frivolity and gravitas. We can assume that all these characteristics grabbed the artist’s attention. Indeed, all Kim Sangjin’s works alternate between serious epistemic contemplation of the self and the world and half-joking nitpicking already aware of its uselessness. Besides his works, Kim Sangjin’s attitude harbors an absurd coexistence of modern thought and postmodern violation. Oasis (2021), another work that began from a meme, is half laughable internet joke and half conceptual study of the operation of signs. A “Caution Wet Floor” sign underwater invites its viewers to laugh. Subverting an object’s purpose to render it meaningless, the strategy vaporizes the signified (content) by transposing the context without damaging the signifier (form). Within the framework of art history, the root of this strategy lies with Duchamp. His infamous Fountain (1917) did not morph the object; merely changing its location from a bathroom to an exhibition space converted the object’s meaning. While Fountain redirects a physical location, Oasis devises a paradoxical situation to make the signifier meaningless.9 Duchamp’s play on the signification of signs often appears in Kim Sangjin’s other works as well. Time_watch sound (2010) emphasizes time differences between sounds to reveal that the measurement of time, which assumes simultaneity, is arbitrary. It is a time-based antithesis of Duchamp’s 3 Standard Stoppages (1913–1914), which unveiled the arbitrariness of measurement through different types of curves formed by threads in the same length. Time_watch sound_2 (2018), which deconstructs linear time by transposing functions, and Jack (2017), which moves the emphasis from the object of signs to the system of signification by uniting the measuring apparatus with the measured object, are both Duchampian interferences that disturb a signification often taken for granted. However, it is safe to ignore such theoretical implications and view Oasis as a funny meme. Is it not the purpose of this work to convey the absurdity of paralyzing slipperiness by filling up with excessive slipperiness?

4. I will disappear (2021), a work in the exhibition with as much gravity as Lo-fi Manifesto_Cloud Flex, compresses the most critical themes in Kim Sangjin’s existing oeuvre. They all lie in its title: “I,” the “language” that denotes it, and their “disappearance.” This work too can be traced back to a meme, this one showing a Wilson brand tennis racket with the “W” logo absent in its shadow. While it seems silly to exclaim, “Where did the W go?!”, that is how we usually are, forgetting time after time that what we see might not be what it seems. Although representation and reality are not equal, we understand, compose, and transform the world through images. In that sense, images can be said to exist prior to, rather than to derive from, reality, and to be involved in forming our consciousness and thinking. As viewers look at I will disappear, that phrase is generated by the difference in colors painted upon the grid. Since it is insubstantial, it is not reflected in the grid’s shadow. Language is thoroughly arbitrary among signs and can capture only parts of the world in simplification and abstraction. Nevertheless, as what structures our consciousness and unconsciousness, language is taken for granted. This transparency of language, so natural that we don’t notice it dominating our cognitive process, is exposed in We are not (2017), which shows video footage of a U.S. satellite exploding, severely shaken by an impact with a rocket. The subtitles imposed on the footage, however, remain steadfast. The text, separated from the image yet defining our comprehension, symbolizes the dogmatic status of language: it cannot precisely coincide with the world, but it still dominates our understanding. The imperfection of language as a representation of the world is also revealed in works that experiment with the omission of signs. Language is a net too sparse to filter the world, annihilating countless senses and experiences that cannot be indicated within the process of becoming language. 95% of data is discarded when converting a WAV sound file into an mp3 format; such data was collected and played alongside the 5% retained by the mp3 file in the work Moonlight sonata (2010), casting the world as a prototype that is lost in its representation.

What about “oneself,” then? The epistemic dilemma—the inability to communicate without language despite its imperfections—can also be applied to the self. Because we cannot survive once we doubt our own integrity, we introduce an illusion called the self. Yet the existence we name “I” is a phenomenon that occurs by comparative differences through ever-changing interactions with the external world. Ever divided between the mind and body, “the world” and “I,” the self and the other, the past and present, we are vulnerable therein, as has been discussed many times in Kim Sangjin’s works. Because we cannot exist without being represented, the “I” has been endlessly duplicated as an image, statue, name, registration number, and other signs. However, none of these representations can wholly contain the “I,” which continues to leak. Human copyright information, a work presenting a replica carrying a replica, signifies the idea of a closed loop of loss. I’m not frantic yet (2016) displays an electric fan facing a mirror, its hard-working movements all but in vain. The work implies the existential nature of representations that strive with limited capability to capture the world. The same goes for the self, which has no choice but to convey itself through a proxy. In that sense, the phrase “I will disappear” printed on the grid gains significance in many ways. The “I” can be seen here as both the subject self and the language sign system. The future tense, which belongs to neither past nor present, attests to a willingness to disappear. Should “I” be a physical entity, “I will disappear” points to the weakening of its physical reality and a gradual transferral to the world of codes. Separately, if the “I” is seen as a language system, “I will disappear” can be understood as a paradigm shift, in which the analog system of representation is replaced by a digital sign system based on numbers. In any case, the disappearance is neither complete nor truthful. No matter how thoroughly machines replace humans, as long as its receptors remain human, an organic body’s physical properties will continue to limit the scope of data. Only signals within humans’ visible and audible ranges are extracted and given significance; this phenomenon indicates that our physical existence limits the potential of data. Humans have been fragmented into a data set that provides information to the matrix, yet the “I” continues to return. In addition, even if the organic language has been pushed behind mathematical numbers, the bureaucratic and patriarchal power of symbols does not disappear. In the sea of data, stirred even more rapidly as time goes by, intense, immediate images and affective economies emerge, rather than slow, static text. Behind them, however, lies the rule of an algorithm that perpetuates prejudice and discrimination, betraying its self-evident and transparent appearance. Thus, the phrase “I will disappear” becomes a paradox, being at once true and false. It is a ghost-like illusion that seems to disappear until you look back and see it appear again.

5. As a sentence in the future tense, “I will disappear” heads toward a future marked by a more intensive semiocapitalism than at present. Perhaps it is closely related to what Baudrillard described as the “great disappearance,” the “division of the subject to infinity, of a serial pulverization of consciousness into all the interstices of reality” made possible by the accelerated labor, time, and fragmentation of the self.10 In this disappearance, a person “is nothing but the residue … of the process of valorization,” and the only thing that exists is an “infinite brain sprawl, an ever-changing mosaic of fractal cells of available nervous energy.”11 Like a canary, Kim Sangjin is the first to detect the signs of value systems being overthrown. The augmentation of tools called reason and rationality unintentionally discards the human epic that began with the Word of God, and its gaping void is filled by the language of such tools.12As space-time, consciousness, and the subject disappear, so does the apocalypse. What exists is only an infinite present, with disappearance omnipresent.

What stance, then, does the artist take toward this numbing landscape of emptiness? Kim Sangjin begins by doubting the naturalization given to the smooth plane of the simulacrum. What is important is to betray the anticipation of what one regards to be natural and disrupt the system of predictions.13 Messiah (2021) is a small expectation, or sought-out way, of escaping a closed world of reduction from which the self has disappeared. Upon an endless gridded plane, there far away is the Messiah so small that he looks like a dot. He is walking but not getting any closer. Nevertheless, he keeps on walking. The Messiah here does not seem to be a savior in the conventional sense. He seems closer to some kind of possibility that creates an interstice out of a smooth, tightly constructed matrix. To Kim Sangjin, this is the absurdity. His methodology of the absurdity, described as “placing midway a twist in the road, pretending to be calm, just simply ending things, asking for trouble, etc. (quoted from the artist),” is a continued raising of issues, joking, and interrupting while recognizing its own uselessness. This futile nitpicking might be a version of Berardian resistance. Berardi sees expressions of passivity, such as uselessness, idleness, dullness, and withdrawal, as forms of radical resistance in a totally capitalist world emphasizing speed, efficiency, and productivity. Exhaustion could put the brakes on this restless climate of productivity.14 Compared with Berardi’s, Kim Sangjin’s strategy of revealing absurdities through doubting naturalization seems both more old-fashioned and more proactive. This is because Kim Sangjin’s strategy can be characterized by a Cartesian subject that begins with doubt15 and eagerness to unfold the practice of thinking. The exhibition’s title, “Lamps in video games use real electricity,” is another truth hidden as a joke. The lamp’s light rendered in the video game is virtual, but also real in the sense that the graphics are manifested using electricity. Setting up such an absurd situation, where simulation and reality coexist, the artist states in all seriousness, complemented by a meme-like attitude, the reality of our current day. Absurdity is discussed not only in his work, but fundamentally in the identity of the artist himself. Is he the descendant of Descartes, sure of his existence as a thinker, or one of today’s bots, clicking away without a thought? Surely we know the answer: he is both. To this extent, Kim Sangjin shares Hito Steyerl’s stance toward intensifying the paradoxical instead of solving it.16 Objects in the mirror are closer than they appear, but that could be just the way they are. There is no need to be perplexed with such duality. Baudrillard already guaranteed that people live in a state of dependency or counter-dependency, to their model, permanently challenging it. He went so far as to state that it is normal to lead a dual life and abnormal not to.17 Indeed, it might be far-fetched to distinguish the normal from the abnormal. Even without me or the artist pointing it out, is it not a known fact that human beings are themselves contradictory and live alongside the absurdity?