Kira Kim

Interview

CV

2014

<Illusory Contour: Hung-Chih Peng & Kira Kim>, Art Issue Gallery, Taipei, Taiwan

2013

<Artist Lunchbox>, Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

2012

<Two Doors> Kira Kim & Shin, Hak-chul, Gallery 157, Seoul, Korea

2010

<Common Good_Climb Every Mountain!>, Doosan Art Center, Seoul, Korea

2009

<Super Mega Factory> Kukje Gallery, Seoul, Korea

<Major Group Exhibitions>

2014

<2014 Dream Society: X brid 2nd The Brilliant Art Project>,Seoul Museum, Seoul, Korea

<Photography & Media: 4 AM>, Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

<Weaving Viewpoint> Space Cottonseed, Singapore, Singapore

2013

<TRANSFER KOREA-NRW> Kunsthalle Dusseldorf, Osthaus Museum Hagen, Germany

<#1_SCENES VS. SCENES>, Buk Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul,Korea

Critic 1

Buoy indicating the Coordinates of Floating Life

Sunyoung Lee (Art Critic)

Floating life in the 21st century Republic of Korea

Kira Kim comprehensively addresses our floating lives in Korea Artist Prize 2015 under the theme of Floating Village. He consumed an initial idea to transform the space in resemblance to a 40-pyeong apartment (approximately 130 m2) for his exhibition. This might deliver a familiar sense of space to some audience who rarely visits the museum. Coincidentally, large-scale development projects for building apartments are underway in Hapjeong-dong, Seoul where Kim’s studio is located and the residential areas and commercial districts adjacent to Hapjeong-dong are currently being reorganized. Kim also has to move his studio due to the skyrocketing rental cost caused by such development. He probably realized how there are others who benefit from the current conditions of Korea’s residential environment, often symbolized as the republic of apartments, while some had to leave their household for the others. Images and messages that flow out of the video installations in the exhibition space are contrary to our expectations for the future as presented by the 40-pyeong apartments, the dream of Korean middle class. While walking through the exhibition space from its entrance to the exit, utopia turns into dystopia, with each room becoming the site of the advent of the respective events.

This is not the place for slow leisurely appreciation of the aesthetics, but a place where the inconvenient truths, we are unaware of or want to avoid, are unlocked one by one. They are truths uncovered in a dark room. It is indecent to convert a white cube redolent of a religious space of the past into an apartment space. However, this is the way in which Kim weaves reality into art. Most of the works he had produced raised controversial issues. Isn’t debate the business of philosophers or politicians? Conveying significance through art is becoming more and more difficult since the onset of contemporary art. Why should an artist do such tough, rough work? Paradoxically, the autonomous nature of art allows such interference. We can interact with life when we are detached from it. On the contrary, if politics is autonomous, people suffer from it. We can say with conviction that our politics is very much so when facing a reality, in which sly old politicians keep coming to the fore. If artistic autonomy is misunderstood, it is ‘art for art’s sake’ but if it works properly, art could be the most ideal model of autonomous life. Art is precious not because it is merely art but because it guarantees the potential for ideal reality.

Art desires not only the freedom of artist but also the freedom of others. Unlike individualism, liberal society stresses that art proves its real worth in that one’s freedom does not clash with another’s freedom in its territory. I have witnessed Kim’s work in person since the early 2000s. He has consistently made comments on the reality from serious assertions to light-hearted jokes. His art has not been a repetition of the same words but comments on the realities he had faced. As both realities and subjects have changed little by little, the content and the form of his remarks have also been altered little by little. For this exhibition at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, He did not have a bombastic intention to showcase all his artistic capabilities, but intends to give full, detailed account of reality, making the best use of the exhibition space of great public attention. It would take considerable amount of time for someone to discover all of the hidden messages in his works. Of course, reading, hearing, and seeing are not the only components of his works. Such method even converts art into consumer good. Don’t we receive enough shocking news from the Internet and evening news reports? The realities he has excavated are shocking as well, but they are not merely to shock, as contemporary art usually does. Kim affects us in that his works come back to us even out of the exhibition space. He poses a question and does not answer but these questions already include the answers within. His works seem to depend on a virtuous cycle, in which viewers see reality through his art and understand it through their own reality. He has consistently executed participatory works but his facture is somewhat individual. He would not think of himself as the one who represents others or their positions. Such universal role of the intellectuals has faded into history after completing their work since the 1980s. He is also not an expert who is only devoted to the division of labor. Such experts have their own limitation to use amazing technology merely as accessories for the dominant system that contribute to the expansive reproduction of contradictions. Not the general public or the people but the era of the multitude; Kira kim is also an individual in this.

Engagement of Artist in Reality

Kira Kim stresses the importance of bonds between individual and individual. In this exhibition, he collaborated with numerous professionals, active in their own fields and worked to maximize these bonds, producing works that evade the logic of any political parties, avoiding political justifications and potency. He is an artist who lets us know how an individual’s will and ability is important in the continuation and expansion of the work beyond mere reflection of the times. The method and style of his work is rather without purpose: he makes the next phase of his work possible by pouring all his energy into solving the current problem rather than saving his energy for an upcoming project. Looking at it from a long-term perspective, his method is not actually unintended but is the only way to endure and survive through reality. When facing his work and life, which are insurmountable by other artists, the wisdom of life comes across, “If you hold onto life, you will die. If you fight death, you will live.” Death appears often in his works since the process of producing artwork itself is commonly imbued with death. Just as a life that strives to forget death is considered ‘superficial,’ art distanced from death is considered ‘surplus.’ Kim’s focus is on the social death. Death in his works is not largely dependent on some ambiguous, existential, or fatalistic reason. Does that make Kim’s art a tool for politics? Art is not political by nature but may become so since the artistic life is often desperate and thorough. Some artists say, “I am about to die if I keep working but I will to die sooner if I cannot keep working.” These people are right. Many insiders of the art scene have the illusion that they eat well and live better through art. Could only the ones who gave up such false expectations from early on become artists? Considering the current desperate situation of artists including Kim, his title Floating Village seems relaxed, as if the term ‘global village’ reminds us of a peaceful atmosphere. This title harks back to a scene of exotic houses or futuristic architectural structures.

His perspective toward the present, not past or future, is condensed in this term. It was only a few decades ago that ghetto towns were lined along the Cheonggye stream area. The artist believes that it wasn’t wealth but a concept of ‘floating’ found in Korean society that helped Korea to achieve rapid growth. ‘Floating’ is not a vision for the 21st century in which we can freely surf in the sea of information or wander elsewhere like a nomad. It merely stands for death. We cannot fully understand this connotation due to the determined and dominant system that is consolidated behind Korea’s floating reality. The concept of ‘floating’ in his work conveys tragic, paradoxical images and connotations that may rise to the surface after death. Ubiquitous death in our society is also found in many works such as On the Bridge and Erased road, And who were without light (2015) on display in this exhibition. Floating Village also includes self-referential comments on the venue, which is merely a temporary space during the 3 months exhibition period. Kim witnesses the unstable lives of people here and now.

He draws attention to the most concrete space in the exhibition. He accentuates that this place, despite of its resemblance to an apartment, is rather an abstract space. Some areas in the republic of apartments situate an individual into certain coordinates of horizontal and vertical axis. The village, name, and size of the apartment one lives in define one’s class today. However, such coordinates can be altered. All members of the society are divided into two categories – those who manage and those being managed – and multitudes of people are degraded to something like chessmen. There is a structural power that causes many to undergo misfortune and tragedy. Kim tries to unlock the nature of such a power that works with another in a dynamic relationship. His works are thus loaded with both implicit and explicit hostile relations. The concept of a ‘floating village’ refers to the relocation and variability rather than individual placing roots in a land of concrete reality. This variability is the hallmark of modernity in contrast with the tradition. Contemporary men are individuals free from the traditions, however this freedom is conditioned by possession, something that aggravates the phenomenon of ‘the rich get richer and the poor get poorer’.

Whether you move into a broader apartment or get thrown out of your home due to redevelopment project, both situations represent ‘floating’ within this era. There is a utopia far away from us and we draw near or grow apart from it but there is no stability. There is no here and now, but only the past we want to forget as soon as possible and the future towards ‘advanced country’ in Floating Village. In this transitional state of reality – the somewhat dynamism of becoming renewed day by day – the impression of Korea that foreigners usually have – are made, but it takes away the crucial element of stability in life. The artist elucidates that Floating Village conveys three connotations. ‘One is the original meaning of information on individuals and images floating online in cyber and Social Network Service spaces. The other one is the social and cultural aspects that remain unsettled like social phenomena and issues such as a lack of politics, temporary employees, lack of households, goose fathers, the 880,000 won generation, political and labor issues, the Sewol ferry incident, and suicides. The last one demonstrates just how important the problems of such floating individuals really are’, Kim reveals.

The innumerable conflicts he suggests arise from the underlying contradictions between labor and capital. The contradiction that comes from the division of Korea is also another significant axis in this exhibition, entangled with others between labor and capital. Floating Village_Government_Consumer_ Individual_The sole in Seoul installed in the entrance of the exhibition space demonstrates the locations where such conflicts took place. This work assumes the role of prelude to his exploration to come, videotaping the places where the conflicts actually occurred but not the concrete aspect of the conflicts themselves. He documents such sites, dragging the camera on the streets. The sites of conflicts include the Seoul Railway Station, Namdaemun, City Hall, Gwanghwamun, and lastly the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul. Typical landmarks are included in his journey, indicating that conflicts are omnipresent. His political economy of conflict is explicitly described in its prelude, emphasized with the symbolic color of red. Redolent of blood, red stands for a fray those results in war. The four-channel video installation on display, features the primary issues within Korean society. Two men whose necks are bound together illustrates a metaphor for how different realities are tangled with one another while a scene of sharing breaths to the dying person reminds of the meaning of the common good.

The Wheel of History

A more macroscopic dimension unfolds after the introductory section of the exhibition. The Red Wheel_You Belong To Me presents a stark contrast between cruel power and the victim who is harassed by the authority. ‘Ideology is always beautiful and peaceful but history shaped by the ideology is always violent and painful’, said the artist. A beautiful woman wearing a ruff collar and a man beaten by water bomb are the metaphors for the contrast of beauty and violence. Power is often decked with beauty but power is violent per se. The countless monuments left on the earth clarify the combination of power and beauty while power internalized in everyday life can even be found in modern times when most monuments have been destroyed. Exquisite portraits in art history were mostly portrayals of the ruling class such as the royal family and other aristocrats. The archaic ruff collar resembling a wheel is a metaphor for those living with wealth and honor. The garment of the collar is adopted as a synecdoche in that it describes a part as the whole and also as metonymy in that it uses an aspect to represent the whole. A ruff collar places emphasis on its wearer’s dominant position, thus leading a mob of angry people to decapitate their rulers in the historical events like the French Revolution.

The body represents symbolic order. And it often becomes the venue of violation. The represented order is where such condition of violation is critically revealed. This is why Kim has collaborated with multitude of professionals in the realm of body language such as actors, performers and dancers. Workers cannot wear a ruff collar. This was the attire for the ruling class (or it was often worn by clowns to satirize rulers). It is also interesting in terms of structure. The pleats flowing to the center draw in things around them. This process is repeated like the turning wheel. The wheel turns here and perhaps have turned in the past.

Friedrich Nietzsche had claimed the idea of eternal recurrence against the linear historicism of his time and stated that only the inevitable returns. In this perspective, power is inevitable. Power will not vanish as long as human society maintains. Power is more or less interactive. As is often the case with history, people have selected their dictator. The wheel of history in Kim’s work travels through the dual wheels.

Unlike the actual process of history, an ideology argues that there may be a determined force leading the history. Kim defamiliarizes the dominant ideology, displaying a gap between imagination and reality through the two contrasting scenes. Whenever a man suffers, the cruel woman’s hysterical laughter grows louder and her white collar gradually becomes red. The red petals also fall to the ground. The figure of power seems to slowly lose potency but exploitation will continue in a different manner. Liquid images of blood and water blurring the two figures in different ways respectively reproduce violent realities, alluding that the boundaries have to be extinguished. The title of this video, The Red Wheel_You Belong To Me, was appropriated from a novel by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. The scenes of getting beaten by the water bomb came from his experience. Pouring down water bombs, as if to suppress fire, is a primal way to cope with danger. Past dictators cracked down on dissidents with violence. Water bombs seem less violent but are the same in that the heterogeneity is removed to keep homogeneity. An obsession with hygiene is reflected on politics: it is particularly influential in the era of totalitarianism.

Discourse in which politics is combined with medicine offers justification to get rid of external enemies who disturb the internal world. This is the way one defines the other, and the way to suppress by exclusion. The contrast between blood and water harks back to biopolitics (Michel Foucault) commenced in the modern times. Unlike blood, water is neither positive nor negative but feels neutral.

Blood is hot whereas water is cold. Water is microscopic power working silently between meshes spreading around life. While blood works in a revolutionary situation where macroscopic power operates, water is quotidian. In Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life, Giorgio Agamben shows a process of integrating natural life into the mechanism of state power and altering politics to biopolitics through preceding research on Michel Foucault who advocated the concept of biopolitics. “Politics here becomes something that lends a certain form to people’s life.” Agamben asserts, “politics is the determination of non-political things (bare life)”. A modern state is governed not by bloody cruel violence but by legitimate violence.

As Walter Benjamin and Jacques Derrida stressed, the law and violence are not opposite to each other. In From the Law to Justice Derrida asks, “how can we distinguish the force of the law from violence we always consider unjust?” In The Name of Benjamin, however, Derrida argues that “Violence is not outside the order of law and things intimidating the law are affiliated with the origin of law.” saying that “there is just a stake in the law.” Like the de-constructivist philosophers, Kim intends to deconstruct the base of legitimate violence. In From the Law to Justice, Derrida considers the structure of law to be deconstructed by nature because its ultimate basis is not founded on justice. As all historical progresses and political opportunities can be found in this possibility of deconstruction, “deconstruction is justice.” The deconstruction of binary oppositions is deconstructivism’s first priority since it keeps up preexistent contradictions. These structures often appear in Kim’s work. However, they do not fight with one another but are used to struggle against invisible enemies.

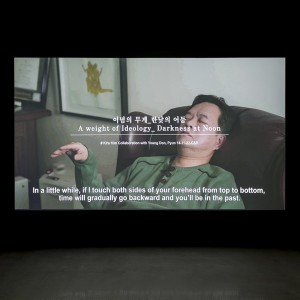

Division, Ideology, and Peace in Everyday Life

Another contradiction in society that Kim points out is the division of the Korean Peninsula. A Weight of Ideology_Darkness at Noon features a painter whose life was devastated. He had made several suicide attempts due to the trauma he suffered around the end of the 1980s when the National Security Law wielded absolute power. This middle-aged man is a real person who had a bitter experience on suspicion of espionage due to his geolgae gurim, a hanging painting. What he had stated during a hypnosis therapy session with a psychiatrist is shocking. The audience is able to hear his statements pertaining to state violence inflicted on an individual. The only thing Kim did was simply arranging a meeting with the doctor and mediates the process of healing without intervention. There is no fiction here, only a potent reality that seems like fiction. The paradoxical title of this work is borrowed from Arthur Koestler’s novel of the same title. The novel addresses the author’s realization that a bright ideology for the revolution concludes to gloomy death in reality during the great purge after the Russian Revolution.

The psychiatrist puts the painter under hypnosis and travels to August 1989 when the event took place. The painter reveals the aspects of state violence that have been imprinted on his body and mind, at times reacts violently to the doctor’s questions. “I was just walking. Some strangers popped out from a car. —– I resisted them, kicking the car door, but I was forcibly pulled into the back seat. I was stuck there as if being flattened. ——- It appeared like I was passing through a huge steel gate. —— There was a hallway lined with steel doors on both sides. ——- They took turns asking different questions and had me write down my answers with a ball-point pen. —- I wrote down my answers, and they asked the same questions again and again. —— I was with investigators around the clock. —– I wrote down my statement on countless pieces of paper and used over 10 ball-point pens. —– I repeated the same content. —— I wanted to stab them.”

The conversation between the doctor and the patient, which lasted for about 40 minutes, reveal how the madness and violence of the system could lead into the madness and violence of an individual. A Weight of Ideology_Darkness at Noon also suggests that the form of confession can be considered in the both the detectives and psychiatrists. Criminals and madman are otherized. Power shifts from outrageous violence to another form, meaning a transition from power is one-sided and suppressive to an immanent power that makes us administer and control ourselves. This is the subject of Michel Foucault’s Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason. The paradoxical articulation of ‘darkness at noon’ harks back to madness. In the exhibition, madness is revealed and analyzed in the public space of an exhibit hall. The origin of his way of addressing the normal-abnormal can trace back to his early exhibition ‘Standard’ (2001). All works on show at this exhibition are videos but drawing still plays a significant role in his art. He has displayed a large number of drawings whose concepts and images pertain to those of ‘The Last Leaf’, an exhibition held at Perigee Gallery in 2014. He showcased immediate images instead of elaborately honed images at the exhibition.

Images are excreted like a madman’s babbles or doodles. As art seeks a multitude of paths, not a single one, and roundabout ways, not shortcuts, rulers consider this an extravagant element. When the concept of production as the highest value reaches its limit, such extravagance will show its strength in earnest. Past communities used to get rid of the risk of excessive production and accumulation by having opportunities to squandering their time regularly as in a festival. However, this risk of excessive production is resolved by war in the globalized era when the competition of all against all is often encouraged. The cause of war is built in contemporary society in which people seek infinite growth: war is not an exceptional event. A doodle getting a clean wall dirty symbolizes an act of breaking taboo. Order in a society is established and maintained through taboo but there have been no taboos violated in history. Drawings done in the style of doodles show the tangled aspects of a multitude of images. Energy that comes out from all holes of his body is involved in and entangled with one another in his drawings that are the basic of all genres of his works including video. His drawings are just enumerated through conjunctions like ‘and’ and ‘or’ but are not constructed organically.

They are not organisms suggestive of hierarchical order but are ‘bodies without organs’ (Gilles Deleuze) possible to be connected like rhizomes. Organisms are faithful consistency while the ‘body without organs’ in which organic order is deconstructed verges on deformation. Drawings often used as the backdrops of his videos like A Weight of Ideology_Darkness at Noon are charged with others’ desire in which power cannot conquer. Drawings in this exhibition are behind the scene like shadows but become a medium to unfold conceptions freely. His video images are not connected smoothly. There are severe leaps and gaps as in his drawings. And an important message is created in empty space and time. His works thus demands imagination, moving beyond seeing and hearing given things. Representing something is not everything in his videos as in drawings. He explains video images in the exhibition are depicted like drawings one by one. A ruff collar is portrayed as a doodle, and the video is completed by adding a narrative to this.

His sculptures and sculptural installations that are not included in this exhibition due to space limitations were also derived from his drawings. This reflects his career: Kim initially pursued painting but later studied sculpture and cultural theories. Drawing is in a sense a language he used immediately after birth. It has been a seed for all types of his works including painting but also sculpture, installation, video and conceptual work in various forms. A Weight of Ideology_The Last Leaf focuses on the South-North dialogue and offers an auditory experience of the current state of division. Innumerable images pertaining to the division of the Korean Peninsula including the first televised meeting of separated families have been put together but unification is still. The artist tries to move beyond any fetishistic visibility under this circumstance. Representationalism triggered by visibility solidifies visual consumption of subject matter. The scenes are sort of spectacles. As Guy Debord concluded in The Society of the Spectacle, they help conclude contradictions as contradictions. Only the voice of a radio actor is heard in the gloomy room. He originally wanted to join in on the meeting of the separated families but could not as the author refused his application. He thus incarnated such a scene with his imagination. Absence and deficiency has been the core of his work rather than making it impossible to achieve.

In terms of themes this work reminds viewers of his work A Weight of Ideology_The Letters to North__Let me know how are you?_On the Yellow Sea (2013). The message ‘Let’s meet and have cold noodles together’ is delivered to the North by setting it adrift on the Yellow Sea. His works dealing with the themes of the division of Korea portray a situation in which both North and South Koreans cannot visit and see each other. Their conversations are all recorded and people in authority from North and South Korea join together, implying that discourse and power are in an immanent relationship. Kim addresses not only the grand discourses like the issue of division itself but also trifle discussions about daily life. He made use of the news programs we watch every day on television in 99 Days_Back to the Future (2015). A news program begins with a news anchor’s fresh remarks, “Hi, Everyone!” but these words are soon followed by the images of various accidents and other incidents. He saves and edits only the beginning of news programs rather than bringing the spotlight to something special. He brings life to reality in a way that makes more of an impact than artwork, leaving them as unprocessed as possible. Of course, artistic devices have the ability to make reality look like reality. His works are the results of his common practice but unveil the nature of seemingly peaceful everyday life.

Beside this work is On the Bridge, which shows how various events cause social death, not personal misfortune. A politician described the sinking of the Sewol ferry as ‘a mere traffic accident,’ a comment that aroused public indignation. Such a quiet death indicates that Korea’s suicide rate is the highest in the OECD. The Sewol ferry disaster is perhaps the biggest event that has greatly impacted our daily lives. This event let us realize that we are in no way comfortable and safe and can never be so. Erased Road And who were without Light (2015) was inspired by the work of Kathe Kollwitz, a German painter who underwent the loss of her son and grandson during the two world wars and became an ardent opponent of war. A maternal image meant to protect children is represented in a dance that discloses the feelings of parents who lost their children in the ferry sinking. Many child performers as well as professional dancers appear in this work.

Kim has collaborated with more than 100 people on this exhibition. Jaeryang Wi, an obscure poet, is one of them. He debuted as a poet while working as a municipal scavenger in Seoul despite the hard labor involved with the disposal of excrement. Kim produced a music video with his poem in collaboration with a film director. He also joined hands with musicians from subculture. A hip-hop performance associating poems with music will be presented at the opening ceremony. Actors, dancers, musicians, filmmakers, psychoanalysts, poets and others are all brought together under one roof. As Kim’s works of engaging in reality are not meant to instrumentalize art, these outsiders join the field of discourse, allowing the venue to become a public sphere. The artist here is a mediator and a mutual subject rather than a creator and subject. Thanks to his feast-like imagination that his themes secured from weighty realities do not sink. They float like buoys, letting us know of the coordinates in the vast sea.

Critic 2

Metamorphosis and Captured Capital

Cho Eun-jung (Art historian/critic)

From Standard to Division, Kira Kim has actively opposed elements of power and authority by critically revealing internal issues of contemporary Korean society. At the same time, however, he works with a prestigious gallery with a stellar collection of famous artists, known for its excellent marketing and sales. These two facts seem to contradict one another, but the situation actually suits Kim perfectly, invoking contemporary art’s tendency to subvert the visual system and raise the alarm to the cognitive worldview. Kim’s works have never left the realm of “contemporary” art as a modifier of the “uncomfortable.” Furthermore, he has never veered from his determined course to pursue new aesthetic languages while touching upon various taboos. Of course, in some ways, his anti-authoritarian works may actually serve to confirm and reinforce the establishment; given that all forms of resistance are inevitably generated by the system of power, they cannot completely erode that system. Nonetheless, once an artist has captured and collected all of the items and issues that we consume, from hamburgers to Slavoj Zizek (b. 1949), they become specimens for examination, like insects soaked in formaldehyde and stuck with pins. In this context, his works have great significance within contemporary Korean society.

Kim maintains that prosperity without harmony and co-existence is violence. Furthermore, he emphasizes that the ideas and concepts that permeate Korean society actually control our lives, like the steam that drives the pistons of an engine. After the early experimental works of his early career, which derived exuberance from his youthful magnanimity, he opened fire on the public, focusing on the minority that we conceal inside ourselves. His remarkable first solo exhibition was entitled Standard, a word that has deep implications for defining contemporary Korean society. For example, every product of a privately owned factory must meet certain “standards” that are defined and managed by the state. These industrial standards serve as a certificate of authenticity that is necessary for the distribution of goods as commodities. Of course, the system of “standardization” and “modernization” that now operates as the state power can also be applied to culture and people. The same system of “standards” provides the impetus for consolidation that allows every Korean to condense the complex lives of historical icons like Shin Saimdang (1504-1551) or King Sejong (r. 1418-1450) into a single unambiguous figure. Naturally, and inevitably, the industrial standards that provide a model for adequacy and restriction are now being applied to members of the society. The application of such standards to individuals and to culture casts various entities within the society as the “Other,” effectively castrating the differences that distinguish individuals. After all, the oppression and violence of of standardization is a self-replicating system that transforms subjects into beings that desire standardization. Kira Kim seeks to expose these beings by laying bare the desire for differentiation and the identity of those that promote such differentiation.

Kim’s works reveal how the grounds for standards are based on and determined by power, so that their principles do not result in integration, but in the production of others. Standards may be used to justify a policy of separation and segregation, no different from the case of patients afflicted with leprosy who were outcast on Sorok Island. Indeed, just as colonialists once justified their oppression with “rational” arguments related to sanitation and development, people with disabilities such as Down’s syndrome and autism are now differentiated by their “non-rational” behaviors. In one of Kim’s works, a video of a disabled person dancing is played at high speed, for a humorous affect. But then, who wouldn’t look funny doing a fast-forwarded dance? Recalling the bow-legged gait of Charlie Chaplin, jaunting back and forth with his cane, viewers are forced to interpret the relationship between the disabled and humor. In Kim’s series Wedding, he takes wedding photos of disabled couples in expensive designer clothes, revealing the inherent relationship between social discrimination and capitalist desires. The people in the photos get a taste of the life of luxury, wearing designer suits and wedding dresses and being photographed like models. For many people, wedding photographs are a normal part of life, but for the subjects of Kim’s photos, they are the realization of an impossible dream. What is the true nature of this unfamiliarity? Too often, we distinguish between disabled people and non-disabled people in terms of abnormal and normal, causing abnormality to be ghettoized. These strategies make people feel helpless, with consequences that are much more horrible than we think.

Ideas and concepts that are utterly devoid of substance can still be the source of true pain for members of society. After years of giving birth and raising children, an ajumma (i.e., middle-aged Korean woman) has inevitably gained weight and lost the desirable physique of her youth; she is now pressured to lose weight in order to be accepted again as a “legitimate” member of society. At one time, a woman’s fat was viewed as the pride of the Mother Goddess, but today, it only represents the laziness and gluttony of capitalism. Only through these unrealistic efforts to overcome involuntary physical responses are ajummas are able to secure a place within reality.

In other works, Kim directs the viewers to see the world through the lens of a camera. One video consists of a point-of-view shot of a person climbing to the roof of a high-rise building, gasping for breath; then, the camera is thrown from the building, forcing the viewers into the perspective of someone committing suicide. Watching this video, many Koreans find their eyes welling up with tears at the crucial moment, as they perhaps connect the video to the aftermath of the I.M.F. crisis of 1997. Tellingly, there is now a popular pun that “I.M.F.” stands for “I am F,” referring to a failing grade at school. The subject in the video is never shown, but the heavy breathing sounds like a man, making people think of a father, who is usually the breadwinner of a family. By sharing the final moments of a person who chose suicide, the audience is forced to feel that they too are so-called “losers” of the society. Putting viewers in such a position is a very clear statement by the artist.

Unlike many prominent Korean artists, Kira Kim did not study art at a university in central Seoul, but he went on to attend Goldsmiths at the University of London, which was also the school of many of the YBAs (Young British Artists) attended. Thus, while in Korea, where there is a clear hierarchy of universities, Kim was somewhat in the margins, but he then moved squarely to the center. Although more and more Korean students are studying in Western countries, it is still relatively rare. In the past, the system for nurturing young minds was overseen by the state, with the goal of cultivating talented people, but today it is part of the desire system of the parents seeking to maintain or advance their own and their children’s social class within the capitalist system. But without question, in Korea, class differences are produced by education. Hence, studying in a Western society that emphasizes the public interest of education may have made Kim more aware of the vulgarity of the capitalistic desires he encountered upon returning to Korea. Thus, it is only natural that his works, which harshly resisted discrimination and prejudice, focused on delving into the system of desire.

Addressing capitalism, he created a series of linguistic works that compare advertisements and the propaganda of political instigation, two aspects of modernization. For example, Coca Killer, which invokes Pop Art and junk food, not only criticizes Korean capitalism, but also serves as a metaphor of Korea’s political situation as generated by Japanese colonialism, the U.S. occupation, and the insurgence of Western capitalism. Another work entitled We are the One reminds every Korean person of the 1988 Seoul Olympics, while also symbolizing the fabrication of “cosmopolitanism” that Koreans have eagerly adopted. Many viewers know Kim best for his contemporary still-life paintings, recalling the tradition of Dutch still-life paintings. Kim’s works have a distinctive “kitsch” sensibility, with their bright and brilliant surfaces inviting more detailed examination. The canvasses are overflowing with different objects, many of which—such as a dirty cup of leftover cola, surrounded by flies and grasshoppers—are modern examples of memento mori, the artistic equivalent of the ancient practice of slaves shouting “Remember death!” while following a general home from a victorious campaign.

The imagery of excess is maximized in Kim’s two series Security Garden as Paranoia and Super Monster. Viewers encounter chosen or collected imagery, as they are forced to consider the inconsistency of objects placed on the shelves of a gallery, as well as the absurdity of objects themed as a “super monster.” Eastern objects collected by Westerners are like words removed from context, which can only be combined as signs. Even so, they come to embody the East, as best exemplified in Dada. As such, the concept of the East or the Orient is eventually symbolized by matters and objects. Even when the objects are placed in a private space, they inherently assume the perspective of Imperialist museums.

In his recent The Last Leaf, Kim transcended the mere consumption of images of the division of the two Koreas, based on “glocalism.” Here, the periphery inside us is symbolized by hovering desires and the internalized images of the others, those with only a voice, but without true substance. Investigating the mechanisms and operations of capitalist society has led Kim to an understanding of the unique phenomena of Korean society as an unlimited orbit of consumption, exploitation, passion, and cynicism. The works of Kira Kim, as the master craftsman of capitalism, reveal the dichotomy of daily life in contemporary Korean society: spectacular yet vacant, modest yet powerful.