Kang Seung Lee

Kang Seung Lee is a multidisciplinary artist who lives and works in Los Angeles and Seoul. His work frequently engages the legacy of transnational queer histories, particularly as they intersect with art history. Lee has exhibited internationally including at Hammer Museum, Los Angeles (2023); Palais de Tokyo, Paris (2023), de Appel, Amsterdam (2023); Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (2022); National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul (2020); and PARTICIPANT INC, New York (2019). Recent solo exhibitions have been held at Vincent Price Art Museum, Los Angeles (2023); Gallery Hyundai, Seoul (2021); and Commonwealth and Council, Los Angeles (2021). He has also participated in New Museum Triennial, New York (2021), and 13th Gwangju Biennial, Gwangju (2021). Lee’s work is in the collections of Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles; National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea; The Getty, Los Angeles; among others.

Interview

CV

Education

2012 MFA, California Institute of the Arts, Valencia, CA, USA

Selected Solo Exhibitions

2023

The Heart of A Hand, Vincent Price Art Museum, Los Angeles, CA, USA

2021

Briefly Gorgeous, Gallery Hyundai, Seoul, Korea

Permanent Visitor, Commonwealth and Council, Los Angeles, CA, USA

2020

Becoming Atmosphere (with Beatriz Cortez), 18th Street Arts Center, Santa Monica, CA, USA

2018

Garden, One and J. Gallery, Seoul, Korea

2017

untitled (la revolución es la solución!), Artpace San Antonio, TX, USA

Leave Of Absence & Absence Without Leave, Commonwealth and Council, Los Angeles, CA, USA

2016

Covers, Los Angeles Contemporary Archive, Los Angeles, CA, USA

2015

Kang Seung Lee: Untitled (Artspeak?), Pitzer College Art Galleries, Claremont, CA, USA

2012

My Nights Are More Beautiful Than Your Days, Centro Cultural Border, Mexico City, Mexico

Selected Group Exhibitions

2023

Made in L.A. 2023: Acts of Living, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Out of the Night of Norms (Out of the Enormous Ennui), Palais de Tokyo, Paris

Queer Threads, San Jose Museum of Quilts and Textiles, San Jose, CA, USA

We Cry Poetry, de Appel, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Strings of Desire, Craft Contemporary, Los Angeles, USA

2022

Let’s Talk: Vulnerable Bodies, Intimate Collectives, Whitney Museum of American Art, New Y ork, NY , USA

Terracotta Friendship, MMCA Korea & Documenta 15, Kassel, Germany

Nosotrxs, Commonwealth and Council × Galería Agustina Ferreyra, Mexico City, Mexico

Annotations, how we are in time and space, Armory Center for the Arts, Pasadena, CA, USA

2021

Soft Water Hard Stone, the 2021 New Museum Triennial, New Museum, New Y ork, NY , USA

Minds Rising, Spirits Tuning, the 13th Gwangju Biennale, Gwangju, Korea

Omniscient: Queer Documentation In an Image Culture, Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA

Gardening, piknic, Seoul, Korea

Queer/Feminism/Praxis in Korea and Korean Diaspora, Rhode Island School of Design, RI, USA

Close to you, MASS MoCA, North Adams, MA, USA

2020

[Glyph], ICA San Diego, Encinitas, CA, USA

Solidarity Spores, Asia Culture Center, Gwangju, Korea

MMCA 2020 Asia Project: Looking for another family, Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea

No Space, Just A Place. Eterotopia, Daelim Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

Queer Correspondence, Cell Project Space, London, UK

When we first arrived…, The Corner at Whitman-Walker, Washington DC, USA

2019

Touching History: Stonewall 50, Palm Springs Art Museum, Palm Springs, CA, USA

Altered After, Participant Inc, New Y ork, NY , USA

Condo London, Mother’s Tankstaion, London, UK

2018

Commonwealth and Council, Tina Kim Gallery, New Y ork, NY , USA

2017

Reconstitution, LAXART, Los Angeles, CA, USA

2016

De la Tierra a la Tierra, Centro Cultural Metropolitano, Quito, Ecuador

Selected Public Projects

2022

la revolución es la solución!, LACMA × Snapchat: Monumental Perspectives, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, CA, USA

2019

QueerArch, Hapjungjigu, Seoul, Korea

2017

Leave Of Absence, Sunset Blvd Digital Billboards, City of West Hollywood + IF Foundation, CA, USA

Selected Residencies and Fellowships

2022

MacDowell Fellowship, USA

2020

18th Street Arts Center Lab Residency, Santa Monica, CA, USA

2019

California Community Foundation Fellowship for Visual Artists, CA, USA

2017

International Artist-In-Residence, Artpace San Antonio, TX, USA

Selected Awards and Grants

2023

Artadia Award, USA

2022

LACMA × Snapchat: Monumental Perspectives, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, CA, USA

2019

apexart International Open Call, NY, USA

2018

Rema Hort Mann Foundation Grant, CA, USA

Critic 1

Practices for Opening a Tangled Future from Memories and Mourning

Nam Woong

Practicing Extended Gardening

#1. The biomes of Papua New Guinea are relatively isolated from external predators and climate change, and therefore free from the usual pressures of survival. The birds of paradise that live in these conditions devise their own methods of seduction in order to mate. One of these birds, the bowerbird, is known for bringing together all kinds of shiny objects in garden-like shelters. Bowerbird males, which are polygamous by nature, do not concern themselves with childcare. In addition, they build bowers, a type of shelter traditionally made with sticks, more as a means to attract females than as a nest, spending much of their time decorating it, except for the three months when they molt. Male bowerbirds will collect different kinds of color-specific materials or objects. Anything which has a certain color to it or is shiny becomes potential nesting material. Among the things they collect are leftovers, garbage, and plastic jewelry discarded by townspeople or left behind by visitors. Another skill the bird has is the ability to mimic the sounds of its environment—they can copy the sounds of other animals and even machines.

#2. Carl Ferris Miller, who was born in the United States in 1921, was assigned to Okinawa, Japan as an interpreter officer in April 1945, and came to Korea as a naval intelligence officer with the Allied forces in 1946. He took a job at the Bank of Korea in 1953 and was naturalized in 1979, taking the Korean name Min Byung-gal. Over the course of his lifetime, Miller studied Korean plants and created an arboretum. He lived much of his life alone, cultivating his arboretum in Cheollipo, before dying in 2002. He promoted the environment and plants of Korea through seed exchange programs with overseas societies, and as early as 1978, he discovered a new plant that was the result of a natural hybridization of the holly tree and Horned Holly. The plant, which grows only on Wando Island in Korea, was recognized as a rare species and named “Wando holly.” It was later registered as Ilex x Wandoensis C. F. Miller & M. Kim with an international botanical society. Today, the Cheollipo Arboretum he left behind opened to the public in stages, starting in 2009.

Today, although their intentions may be different, we may be able to begin discussing Kang Seung Lee’s work by overlapping the bowerbird’s behavior and doing three things: explaining the behavior of the male bowerbird as a decorative act that defies uselessness, even if it is not practical; making the assumption that it is a courtship gesture, but not solely for the purpose of mating; and imagining the function of this behavior as a way to gather or alert other birds by mimicking the sounds of the environment. The bowers in Papua New Guinea, often referred to as “gardens,” are the result of the collection and arrangement of surrounding objects, thus becoming part of the landscape. As a result, if we turn our attention to the life of Min Byung-gal, we can also consider migrating to and settling down in a foreign country, thereby revealing the invisible to the outside world and consequently expanding connections with the outside world.

Kang Seung Lee, who is now based in the United States, used the concept of a “garden” as the theme of his first solo exhibition in Korea in November 2018. Held at ONE AND J Gallery, Garden showed a place and loss—somewhere to remember loss—with the activity of gardening used to visualize a place for memory and mourning. In other words, the exhibition showed forms of art though gardening. Taking soil from Tapgol Park (formerly referred to as Pagoda Park) and Namsan Mountain, as well as Prospect Cottage in England, and then burying it in a “place beyond,” the artist stages a burial ritual, while also carefully utilizing small objects in the process.

Tapgol Park and Namsan Mountain, both located in Seoul, are places where gay and transgender people used to cruise in the past—and today where they still gather at night—and have always harbored the shadows of physical contacts and encounters that have not been officially recorded. Like unnamed sand and weeds, these people have long been uncounted or rejected, and often portrayed as perverts who occupy sparsely populated urban spaces, as well as disorderly boundary-crossers who are vulnerable to crackdowns and public scrutiny. Moreover, the spaces they occupy are often referred to as slums and remain in need of maintenance and development.

For Garden, the artist calls on Joon-soo Oh, a longtime member of the Korean gay men’s human rights group Chingusai, which has been active in the inner city of Seoul for thirty years. At the same time, Lee connects to the garden of British queer filmmaker Derek Jarman. Surrounding a cottage on a barren plot of land in Dungeness, Kent, southern England, Jarman arranged waste materials from the beach and planted grasses and flowers native to the coast. With no fences and not a single tree taller than an adult, the space is still visited by people. Today, it is an empty area in a public space, a dark site where people meet with a collection of trash and native plants from the area, and a garden where anything can find its way in, even during times of constant management because there is no fence there. Lee’s work of bridging the gap between Joon-soo Oh and Derek Jarman invites anonymous members of the public to take part in the garden, those who might otherwise be wandering around a public space and waiting for someone, and welcomes the uninvited by overlapping private land touched by an individual on top of a public space. This can also be approached as an attempt to intervene in the order of the plaza by making those who have not been publicly recorded in the city’s history appear in the public space, demanding a share of the citizenry in the process.

The act of burying things, which takes place in both locations, intertwines pairs of differences, whether they are places and times, lives and life circumstances, public and private lives, or memories of the two men who are bound together by similar sexual orientation and illness. The two unrelated men, Oh and Jarman, shared a common life as homosexuals who died of HIV/AIDS in 1998 and 1994, respectively. Even now, HIV/AIDS, a global epidemic that was often stigmatized as a “gay cancer” in the past, evokes images of mourning and funerals over the garden here in England. A kind of patchwork that connects the Korean park which functioned as a nighttime ghetto with the garden of someone who would have wandered through a park also extends to the actual stitching of the artwork. The artist embroiders hemp cloth with gold thread, the objects he embroiders being either shapes designed from excerpts of texts from his research or images of small objects. On top of the ritualistic documentation of burying materials collected from one place in the other place, the method of using handicraft-based labor to add the meaning of mourning to the artwork is reminiscent of a work for which quilting—a traditional craft still practiced by some North American families—was used to preserve the records and faces of the deceased in fabric throughout North America and elsewhere during the HIV/AIDS crisis, while simultaneously recalling the shrouds that cover the body.

The work of interconnecting not only what is remembered but also how it is remembered shows that the semantics behind gardening as an art form is extended beyond the simple act of planting flowers and trees. Gardens are somewhat conservative in that they involve the selection and placement of plants in a fenced-in space and the creation and maintenance of artificial landscapes. Crucially, however, gardens cannot help embracing changes, such as decaying and renewing themselves. Unexpected animals arrive to nest or trample on the grass. Sometimes seeds fly in from outside the boundaries and weeds grow. The landscape changes with the weather and the seasons. The act of gardening utilizes even these changes as elements of creation and appreciation. Kang Seung Lee shows exquisite skill in expanding the formats of gardening while making the gardening methodology compatible with a white cube, library, and museum. At the point where gardener and artist become one and the same—yet diverge as art—Lee manages to reference Derek Jarman’s gardening practice of collecting useless materials, though in the place of uselessness, he superimposes the strands of ethnographic history. He then follows the sparse traces of history, devises a methodology to reveal them, and intervenes in the linear order of time and space. In such a way, the artist’s experience of migrating from Korea to the United States may have served as the background and motivation for sculpting the unilluminated from the uneven histories of race and gender to bring them into contact with someone else in a different space and time to create a synergistic sensibility.

The sensory labor in a garden presents a formal extension of artistic creation followed by curatorial practice. The artist arranges reference materials, drawings, and objects in the exhibition space, connecting and reorganizing their own narratives and subject matters. The connections are not made at random, but use specific keywords as quilting points. Images of HIV/AIDS, queerness, missing histories, and shame are private, and they lead to an attempt to intervene in the previously natural order of the white cube with faces and names that were only treated as private and have never been publicized. What is noteworthy is that the act of collecting and arranging images of fragments and parts of people’s lives confesses not only forgotten memories but also attempts to remember them as inevitably fragile. The act of searching for traces of memories leaves the existence of a void, while connecting partial sentences, images, and fragmentary objects, rather than recreating them with the intention of fully restoring memories. Although the arrangement is incomplete and fluid, it holds the possibility that various meanings can be discovered from it. By collaging drawings and installations, the artist invites viewers to come and make the effort to connect and rediscover the meaning of each. This leaves clues—about the bowerbird, the life of Min Byung-gal, and the Mnemosyne Atlas methodology—that can be aesthetically appropriated with gardening as a link. Thus, while strongly connecting the physiology of the bowerbird and the life of Min Byung-gal, both of which inspire critical interpretations of gardening as an extended field of art, Kang Seung Lee directly recalls Derek Jarman, who spent his later years tending to Prospect Cottage in Dungeness. Furthermore, Lee even alludes to the Mnemosyne Atlas methodology that Avi Warburg used to construct art history, weaving together disciplines and histories regardless of source or material much earlier than that. Ultimately, the incompletely recorded materials of these precarious people lead to a present-day practice that connects at the artist’s fingertips the vulnerable aspects of memories that history has overlooked.

Expanding Connections by Starting from Imperfections

The conceptual meaning of a garden—which requires researching the space and its surroundings, and constantly managing and refining all of it—is both a motivation and a reason for summoning the places of those who have always been consumed with an image of shame only. The attempt to connect gardening as a methodology of artistic work opens up the possibility of expanding the interpretation of gardening as well as its skill in the curation of art spaces.

In the exhibition QueerArch, held at the gallery Hapjungjigu in October 2019, the attempt to grope for disturbing faces in the media and unremembered communities became more serious. Here, Lee was not only an artist but also a curator and exhibition director. As he organized an exhibition that connected “queer” with “history” as the main keywords, he called on artists and colleagues from all walks of life. (To be more precise, in Lee’s own mind, these people became immediate colleagues of his by being called upon to work together.) If the faces in the drawings are objects of mourning and memory, fellow artists and activists remember and honor them based on the drawings and give them contemporary meaning.

It was at QueerArch that Lee’s curatorial practice really came into its own. In the 2019 exhibition at Hapjeongjigu, he invited artists to participate in the act of collecting and arranging, and encouraged them to create artworks based on a public archive named the Korea Queer Archive. Fashion designer Kim Se Hyung (a.k.a. AJO), archivist and researcher Ruin, artist and stage performer Moon Sang Hoon, drag performer Azangman, visual designer Kyungmin Lee, and sculptor Haneyl Choi were invited as Lee’s colleagues to participate in the exhibition and present queer histories, as well as to present queer collecting and archiving practices related to queer histories. Although it falls under the category of art curation, the attempt to gather fellow queer artists, give them a mission based on Korean queer history, and exhibit their proposed works also had the effect of creating a temporary sense of community. The participants researched the reference materials and recreated formats that reflected their own context. This, of course, was based on thirty years of LGBTQ+ activism, which had continued to demand a place in the public realm for LGBTQ+ people who had historically been forced to live in marginalized environments. It is worth remembering that while the previous Garden exhibition was made possible with the help of Chingusai, a Korean gay men’s human rights group that Joon-soo Oh was an active part of, QueerArch was able to take their materials out into the open and display them or utilize them as material for the exhibition through a collaboration with the Korea Queer Archive. Conversely, collecting materials by tracking a community, and coming up with devices to preserve them, can actually contribute to the community. Therefore, the inclusion of collaborating artists in the exhibition credits is a reminder that Lee’s exhibition cannot remain a personal achievement and narrative. The work of organizing the exhibition by making connections inside and outside of art allows us to perceive a queer community that has once again responded to a crisis, that is, the contour of a queer community in which members sought each other out in order not to be isolated in a crisis, and that sought safety and a new tomorrow through a crisis.

Furthermore, Briefly Gorgeous, an exhibition held at Gallery Hyundai in 2021, shows how archival practices should respond to a situation where the past cannot be fully summoned and the present is in crisis. In the shadow of social disasters, including the outbreak of epidemics, everyday social inequality and discrimination are magnified. Vulnerable places and groups are targeted and attacked, and those who are not counted as citizens are not included in those to be protected through the prevention of disasters. The garden work of uprooting diseased branches and species is carried out in the world as discipline, confinement, targeting, and stigmatization in a life-or-death environment. In the midst of any pandemic, confused authorities and the media take pointless ad hoc measures, while being quick to target specific groups, accusing them of spreading a contagion through their senseless disregard for taking any precautionary steps. Yet the people they target are often the most vulnerable and in desperate need of community. In 2020, migrants, delivery workers, and gay men in clubs were vilified with spreading COVID-19. Early the following year, a series of transgender suicides made news in Korea.

The disaster of a disease-ridden epidemic is nothing new. For the 2021 exhibition, Lee thought back to Asian artists among the artists who died or survived the HIV/AIDS crisis, including photographer Tseng Kwong Chi, who was born in Hong Kong and died in New York in 1990, and Goh Choo San, a Singaporean choreographer and ballet dancer who brought fame to the Washington Ballet in the 1980s. In addition, he juxtaposed drawings of the late Kim Ki-hong, a South Korean transgender activist and music teacher, and the late Sergeant Byun Hee-soo, who was forcibly discharged from the Korean Army after undergoing gender reassignment surgery, both of whom died in early 2021. His process of shedding new light on them is often described as an attempt to challenge not only heteronormativity but also white-oriented queer histories. Recently, he seeks to sculpt forms of connection by extending his artistic attempt to ever-present contemporary crises. Photographs and video footage, ceramics and canvas paintings, notes and doodles, flowers and grasses, and maps all showed a careful arrangement of fragmentary images, texts, and objects, rather than being something definitive or monumental. The reconstructions, which reference patchworks and mosaics, integrate past and present times—those who stood or fell in different regions and contexts, and contemporary perceptions and sensory elements—while maintaining a particular sense of place. Together with El Salvadoran writer Beatriz Cortez, the artist asked his colleagues what a “queer future” would look like, and then asked them to complete their sentences in the future tense: “When the future comes, I will…” Those sentences would have been a collective mantra that gathered the longings of individuals dreaming of an ideal future instead of the status quo based on the faded records of those who had not been counted in the trajectory of history and on the desire of the person seeking to find those hard-to-find records.

In the basement of the exhibition hall, the logo of Itaewon’s King Club, a nightclub that was targeted during the COVID-19 spread in Korea, set up as an assembled puzzle-like object, with music playlists from fellow artists played in a club-lit space. While the lights, a mirror ball, and objects unfolded to the music in the basement, archival materials were placed on the first floor, while the second-floor walls were covered with hand-drawn faces. The exhibition was organized so that visitors could explore the underground club, the archive on the first floor, and the specific faces and traces of one’s life on the second floor. This came about as a result of observing queer spaces in Korea and reorganizing the flow of their functions in the building structure of the museum. An example of memories and a sense of community being embodied in a specific space seemed to have been organized in a more community-oriented form than in the special exhibition Looking for Another Family (2020), which was held at the MMCA Seoul a year earlier than Briefly Gorgeous. For the 2020 special exhibition, Kang Seung Lee created a lounge-like reading space. The books selected by literary critic Hyejin Oh, while wary of being treated (as described by Oh at the time) as “a synecdoche of a certain purposive intellectual history or a fetishized object of queer heterotopia” or “an obsession with the queer,” constituted an arbitrary and fluid network, revealing that this exhibition space also has the meaning of a temporary occupation. However, unlike Lee’s intention, the open space became the hub of the exhibition, giving the impression of connecting the works by other artists around it. The viewers wandered around, thumbing through materials and looking at videos and drawings. The arranged shelves and furniture functioned as partly closed partitions and, at the same time, fences that blurred the boundaries between the two—and yet also connecting the two. In and around them, Lee displayed a collection of queer-specific content and images. The nature of the site, where a community’s private history and archives are knotted together in a public space, was reminiscent of the ghettoized nature of a certain group (such as queer people, for example), but also of the design of urban spaces that connect in all directions.

However, the work at the special exhibition may have left a different impression on visitors than Lee’s Covers (QueerArch) (2019/2020), in which he collected the covers of publications covering queer-related papers, magazines, and books, made them into scrapbooks and wallpaper, and pasted them all over the exhibition space. The work, which seemed to encompass everything at once, gave the impression of overwhelming the space by spreading vertically and horizontally the recorded materials and research of those who have somehow created their own language and grammar despite being placed in a peripheral position within the existing market and system. Indeed, it created the effect of a quantitative spectacle, while also relying on an archive that spans the keyword and framework of “queer.” Although this is not like the direction of Oh’s notes from the earlier book selection, we need to keep in mind that this is another limitation of the work: it simply cannot be all-encompassing. Lee’s work, which is incomplete and promises to be endlessly continued, focuses on admitting that nothing can be fully collected and given meaning, and not on uphold an exclusive identity by giving meaning to everything. Thus, a methodology that is close to a collectomania emerges as one of selection and editing when it comes to exhibition curatorial practices, including archival spaces. In this case, the markers of whose point of view or criteria have been applied complement each other by inserting collective opinions into empty spaces and by embracing ways to secure and organize a space where we can examine those opinions one by one. The imperfection of memories and conservation are the inevitable limitations of any community and the basis of all connection.

Disturbing Memories and a Tangled Future

Lee overlaps the records of public and private lives, featuring past figures and surviving subjects—as well as the memories of life and death—all in one exhibition space. The artist juxtaposes subject matters with different “grammar” (i.e., ways of interpreting things or people) and value, while also reinterpreting discovered reference materials and proposing new “grammar” rules. This artistic practice follows the unfair context in which the lives of others are obscured, and reveals those people who have been filtered through this unfairness.

However, the virtue of being revealed also becomes a concern for exposure. This is because the lives and faces introduced in art spaces can be easily bleached as objects of representation and aesthetic representation. We may suspect one thing here: The traces of people’s lives that the artist has drawn from—the representations that failed to be remembered earlier—may serve to remember and introduce the times and faces he tried to draw from while only giving them meaning as the lives of the Others. Or, on the contrary, does the work of targeting the Others not easily leave behind an attitude of respect and consideration? In other words, the attitude of respect for vulnerable records and objects secures the virtue of giving public meaning to the memories, people, and materials that the artist has unearthed by presenting them in the exhibition hall. On the other hand, there is also a concern that he may inadvertently capture someone as the Other. This concern acts as a reason for doing nothing more than intervening in the targeted beings and renewing their time in the form of art. In other words, there is an essential dilemma in dealing with the Other: the revealer and the revealed are not placed in equal positions. When other people’s bodies, their sensory representations and records, and their lives and histories are placed in the forgotten and obscured realm, they are once again framed as the Other that should be discovered and named. One-sided referencing & representation, and the attitude of respect and consideration seem to be contradictory, but they are common in that they separate the subject from the Other without doubt. Therefore, the position of the Other as an archival object once again summons the status of the subject who collects, edits, reconstructs, and uploads it to the art space. Although the two kinds of attitudes may reflect on themselves, do they not inevitably uphold the position of the artist as a reflective subject who reveals and rearranges subject matters that remain hidden? What kind of destructive force can this subject secure? In addition, how can the lives and bodies that appear at the invitation of the artist go beyond restoring honor from the past shame and continue with their disturbing values and desires?

Before answering those questions directly, let us shift or attention to the drawings for a moment and take a slight detour. The pencil (graphite) drawings, which delicately match the light and shade, as well as the tone, encompass a variety of subject matters, not only figures but also newspaper articles, local vegetation, and pebbles. In short, he does not miss any letter of any word, any crinkle in the paper, or any holes in the stones he comes upon. However, rather than describing the subject matters with lines of conviction, his pencil wanders across the canvas like a smudge, making and crushing shapes, with the trajectory of this crushing creating the shapes. Sometimes figures are drawn partly erased. The marks of erasure and crushing remain like smoke or stains, appearing as the evaporation of a figure’s place. This is both a meticulous depiction of the time he failed to capture and a gesture of refusing to be captured in the first place by leaving the faces of others as ghosts. He thoroughly draws the records in his hands, but leaves them blank or burns the corners to create soot, as if to admit that he cannot fully capture them. At this point, it would be easy to categorize his work as a typical representation of the inability to capture the faces of others.

Lee’s drawings also include renditions inspired from the photo series East Meets West (1979-1989) by the aforementioned photographer, Tseng Kwong Chi. The way Tseng practiced his art during his lifetime leaves clues as to how and approach Lee’s drawings differently. Wearing sunglasses and dressed in a Mao suit, Tseng Kwong Chi pressed a button in his hand to take pictures in front of iconic and typical American and European landscapes. The resulting pictures are said to have performed a stereotype perceived by the eyes of others looking at Asian people. The recorded materials frame one’s isolation as being part of the landscape, and show the tension and competition of the gazes that refuse to be captured by hiding the artist’s own eyes. In Kang Seung Lee’s case, he draws the photographs someone left behind, erasing the person’s face rather than trying to recreate it, and imagining the spot where it was erased. The artist’s painstakingly precise depiction suggests that the motivation for his drawings is the impulse to thoroughly express a longing for the memories that cannot be fully recalled and restored. Additionally, the method of erasing and leaving empty spaces in drawings makes a critical reference—from a contemporary perspective—to Tseng’s tireless attempts to devise a form of visualizing himself while at the same time distancing himself from the lens through which people of color were viewed. It would not be unreasonable to approach this as an exquisite form of memorializing an artist who passed away from HIV/AIDS. For him, Lee took into account the concern that the perspective Tseng took during his lifetime might be captured as an archetype of a possible choice by an East Asian artist who lived in the developed world.

Conversely, how should we understand Lee’s conflicting modes of representation that bring to the forefront the faces of Joon-soo Oh, Kim Ki-hong, Byun Hee-soo, and other unnamed queer figures from the past? The statuses of those who can claim citizenship by revealing themselves and those who erase themselves from the race, nationality, and gender stereotypes that imprison them are not that far apart. However, it is important to note that the choice to reveal or not reveal depends on the local political situation, who is the Other that is represented as an object of art, what lifelong attitude the person expressed during their lifetime, and the social context in which it was formed. There are people who have resisted the power of representation that categorized them as subordinate subjects and repeatedly reproduced stereotypes. Beyond them, we also need to remember the names and faces that those people—those same people who had not been recognized behind the over-represented—desperately tried to leave behind.

We need to note that the method of representation, that is, one which is devised by looking closely at the environment of those who lived in those days, continuously reconstructs relationships by looking at the context of the time and leaving room for reinterpretation from a contemporary perspective, rather than only looking at others who have lived or died earlier as the objects. Thus, Lee not only invites fellow artists, writers, activists, and others to engage in critical archival practices as he seeks to interconnect contemporaries but also to include artists of past generations as contemporary colleagues, invoking the methodologies of art practiced during their lifetimes to renew and give new meaning to these methodologies in the present.

Lee’s collage-like arrangements and drawing methodology have recently been presented in the form of gestures, on the stage and on the screen. Clad in the easily forgotten rhythms of the body, the artist takes up the motions of the past and creates contemporary gestures. In fact, he designed a font derived from the American Sign Language used by Chinese-American artist Martin Wong, who died of AIDS, to apply it to sentences in Lee’s own works. In The Heart of A Hand, Filipino transgender/nonbinary choreographer Joshua Serafin deconstructs Goh Choo San’s 1981 dance Configurations to set it to the music of Seoul-based transgender musician KIRARA. The artist’s call to remember and adopt the gestures of queer artists—but also to express one’s own disturbing gestures and gazes right now—may be a prelude to a more radical gesture: While adopting the past as an artist-subject, he cannot simply make divisions between the past and present. Lazarus, which premiered at the Korea Artist Prize exhibition, referenced and networked simultaneously, like the release of a held breath. Based on Goh Choo San’s original ballet Unknown Territory and recreated by choreographer Daeun Jung, two male dancers express their interaction with each other by donning and doffing costumes with two dress shirts sewn together up and down, in reference to Lazarus (1993), the last known work of Brazilian conceptual artist José Leonilson. By incorporating text from queer Chicano artist Samuel Rodriguez’s 1998 experimental video Your Denim Shirt and transcribing it into a font using the American Sign Language invented by Martin Wong for his paintings, and by collaborating with L.A.-based filmmaker Nathan Mercury Kim and using KIRARA’s music, the creation process is in the form of condensing the separation between past and present, as well as the collaboration of contemporary artists, onto a single stage. This allows for the prospect that his future work may attempt to cross-reference and even appropriate between collaborators and references. It invites us to examine the marks of faces and bodies that appear erased in Lee’s drawings, and the outlines of faces and bodies that reappear from them.

If the above stages imply complex references and processes, asking the viewer to make an intellectual effort to appreciate them, his objets d’art reveal the process of more intuitively disparate contexts meeting in a material way, meaning viewers can see this aspect concentrated throughout his ceramic works. He collects soil from different places, kneads it, fires it in a kiln, and makes pots, which he then fills with other soil and transplants plants grown by a person he remembers. While the objects intersect different points of reference, each material functions as its own indicator of memory, and the viewers can savor and connect with the memories by alternating between the captions and the ceramic objects. The methodology of ceramics is a mashup of subject matters and materials beyond collection and collage, opening up the venue for networking through a stage where gestures and rhythms are generated again, not only referencing and paying homage to the past but also weaving in collaboration with contemporary living artists.

Conclusion

The journey of expanding the collaborative relationships with a work’s references and renewing them by crossing the boundaries between the two reminds us that the artist-subject is also dependent on the time of others, that the artist is in a state of decay and imperfection, and, as a result, that he can only survive by being captured and occupied by others. He proposes the phrase “Who will care for our caretakers?” by American lesbian poet Pamela Sneed as the title of his Korea Artist Prize 2023 exhibition. Written while having her colleagues pass away during the AIDS crisis in the 1980s and 1990s, the sentence looks beyond the perspective of the mourning survivor to recognize that the mourner in the here and now can also be someone else who will die damaged at any moment. It passes through the challenge of the time to rethink—beyond the one-sided memory of a single party—a shared life lived, mutual care, tangled care that surpasses the care system and the care industry, and the social structure of care for sharing the anxieties of life around poverty and aging beyond the exclusive family model.

In an interview for the Korea Artist Prize 2023, Kang Seung Lee described himself as a messenger. This somewhat qualifying expression asks that he examine what languages he needs to master in order to connect different times and regions, and what devices he needs to employ in order to articulate and secure a life worth living. It goes beyond compiling records and reference materials and organizing exhibitions, and asks him to take up the position of a director who re-invents gestures from the past that have not been given meaning, and to then make them appear on stage. Furthermore, contemporary collaborators and colleagues are asked to provide an opportunity where co-creation can continue to generate discussion and discourse based on cross-reference and coordination. This suggests that the work of remembering and the work of unlocking time can happen simultaneously. A more perceptive reader may even recognize that this act of unearthing and connecting has been described as queer temporality, but it is not so different from the practice of democracy.

Kang Seung Lee put the images of shame at the forefront. Those people who were constantly “discovered” or “caught” in the titles described with revelry and disturbance, and who could easily evaporate as objects of “reportage,” instead appear in the limelight. The image he put on the forefront of the exhibition is that of a group of people who, in the face of a violent outside gaze, were decorating themselves in a dark place at night very disturbingly, and left behind the image of themselves as if for commemoration. Of course, society would not have perceived the decorations they wanted to show off as harmless. Considered perverted, disturbing, and not to be seen in public, they were constantly subjected to crackdowns and gossiped about, but in the end, they refused to give up their expressions and performances and kept themselves attached to the screen on which they were performing. It is not a jump in logic to interpret this as a hope and a sign of fragile connection amidst struggle, degradation, isolation, and a legacy of gardening that each of them must have cultivated. The attempt to push his work based on memory and collection into the possibility of radical care leads to an attitude of collaboration which presupposes that—like those who mourn, discover something for mourning, and have difficulty remembering someone fully—one’s work is dependent on the traces of others. Calling on colleagues and devising attempts to reproduce the programs of community may very well be the efficacy of the art that Kang Seung Lee has maintained throughout his career.

The impossible attempts to convey the temperature of one’s unreachable body exceeds the artist’s capacity as a subject. At the same time, however, these attempts connect through him. He continues to create and devise places to create a time to come and a time to open up, finding colleagues and connections along the way. While walking through the thoughtfully collected and rearranged exhibition, I consider the forms of aesthetic touch that the artist has been devising, and think how and to whom this time will open or close.

Critic 2

Setting Things in Motion

Kavior Moon

Community, collaboration, and continual transformation have been central to the works of South Korea–born, Los Angeles–based artist Kang Seung Lee. For over ten years, he has developed a research-based practice that mines public and private archives to revitalize the works and legacies of queer artists, writers, dancers, and gay and trans rights activists who have passed away. Some of these transnational historical figures have remained well-known in the present-day, whereas others have fallen into relative obscurity. To create his works, he has engaged closely with caretakers of these archives and with those still living who were involved in the histories contained therein. Lee has employed a range of materials and techniques in his works, including graphite drawing on paper, embroidery on sambe cloth, collaging found objects, among others. He has also collaborated with artists and other cultural producers in his queer community to create ongoing, open-ended art projects, group exhibitions, and videos.

Community and collaboration have structured Lee’s practice since his earliest exhibited works, such as his Untitled (Artspeak?) (2014–ongoing). Billed as a “common-sense guide,” Artspeak: A Guide to Contemporary Ideas, Movements, and Buzzwords, 1945 to the Present is a reference book that defines a number of art movements and terms used in contemporary art; it also features a timeline that lists, year by year, events categorized as “world history” or “art history.” To make this work, Lee invited around twenty people in his social circles in Los Angeles and Cal Arts (where he received his MFA) to collaborate; each person was asked to “edit” an enlarged, hand-drawn copy of the timeline page in Artspeak that shows their year of birth. The group of people that Lee invited were diverse in terms of their age, gender, race, sexual orientation, and cultural backgrounds.1 In the wide blank margins that Lee used to frame each book page, the participants added their own annotations, anecdotes, events, and drawings of artworks, musicians, filmmakers, and others left out by Artspeak. The edits collectively undermine the implicit masculinist, heterosexual, and colonialist point of view in Artspeak’s version of history by introducing multiple historical narratives, ones reflective of the varied interests and personal backgrounds of Lee’s international, intergenerational community at the time.2

In recent years, Lee’s communal approach has become more dynamic and open-ended, as evident in his so-called Harvey project, begun around 2019. This project has its origins in a work titled Archive in Dirt (2019–ongoing) by fellow artist and friend Julie Tolentino. Archive in Dirt consists of a potted Christmas cactus plant that Tolentino grew from a small cutting; this cutting was taken from a “mother” plant that had belonged to San Francisco Supervisor Harvey Milk (1930–1978), one of the first openly gay elected officials in the U.S. who was tragically assassinated less than a year after taking office. Tolentino received the cactus cutting—which arrived very limp—in a mailed envelope alongside print ephemera from a queer activist and archivist friend, who had in turn received cuttings from one of Milk’s former roommates (who had been giving cuttings to various friends over the years).3 When Lee encountered Tolentino’s work, he was touched by how generations of people had taken care of and propagated Milk’s plant during the four decades since his death.4 Since 2019, Lee has helped Tolentino propagate the “Harvey” cactus and has created his own artworks in response to the growing number of plants, which have been entrusted to others in their network of queer friends. The “Harvey” project generates acts of caring and gifting that have enlivened a sense of community around a shared desire to keep Milk’s memory alive and present.

Continual transformation is integral to the “Harvey” project—which literally changes form as new generations of cuttings and owners come into being—as well as Lee’s larger artistic practice. In his works, Lee doesn’t claim to use original subject matter, but rather he sees his mode of making in terms of “appropriation.”5 From archives, books, and particular locations, he collects found images, objects, organic matter, and other materials with specific histories and symbolic resonances. These source materials are recontextualized and often translated into other mediums—especially drawing, embroidery, collage, and video, as I discuss in this essay—in ways that transform their original meanings. In this way, his works look backward and forward in time, functioning as spaces for remembrance as well as opening up new possibilities.

Drawing: Presence and Absence

A number of Lee’s graphite drawings memorialize queer lives that have been cut short, such as those presented in his exhibition Absence without Leave (2016–2017) at Commonwealth and Council, in Los Angeles. For this show, he presented meticulous graphite drawings of photographs that capture the milieu of gay life in the 1970s and 80s, particularly in New York.6 Source photographs for this series include a self-portrait by Robert Mapplethorpe, a portrait of David Wojnarowicz by Peter Hujar, a portrait of Martin Wong by Peter Bellamy, scenes of gay cruising at the Hudson River piers taken by Alvin Baltrop and Leonard Fink, among others. Lee’s drawings faithfully reproduce the photographs save for one part: the human figures are blurred, rendered unrecognizable, made to appear as if they are disappearing into a cloud of smoke. On the one hand, the figures’ erasure alludes to the traumatic devastation wrought by AIDS in queer communities in New York and other cities around the world, as well as how politicians and governments initially refused to recognize the epidemic. In the U.S. alone, hundreds of thousands of people died from AIDS or AIDS-related complications by the end of the 1990s, including Mapplethorpe, Wojnarowicz, Hujar, Wong, and Fink. Thus, the drawings can be read as grieving loss, as art historian Jung Joon Lee has argued.7 On the other hand, the figures’ erasure also indicates Lee’s artistic intervention into these images, a conceptual prompt that can be read as an opening dialogue between Lee and these artists of a previous generation. Lee has stated: “I would like my work to question the erasure of others who came before and remain unseen, to generate conversations about the space that holds intergenerational connections and care, and to be an invitation to reimagine invisibility as potentiality.”8 In this way, the drawings can also be read as affirmations of presence.

The laborious, time-consuming nature of Lee’s method of drawing encourages viewers to linger and slow down their perception of his works. This is particularly the case with his larger-scale drawings, such as Untitled (Joon-soo Oh’s letter) (2018). Whereas many of Lee’s drawings of photographs, such as from his Absence without Leave series, are intimately sized at around 32 x 28 cm, Untitled (Joon-soo Oh’s letter) is about five times as large, measuring 160 x 120 cm. The enlarged scale allows one to read easily the content of the letter by Korean writer and poet Joon-soo Oh (1964–1998). It is a searing account of his feelings of loneliness as he listens to music by popular singer Yong Pil Cho and imagines himself contracting AIDS and dying from it. He expresses his deeply rooted fear of being forgotten, as if his life had not mattered. Oh was one of the first gay men in South Korea to publicly disclose that he was HIV positive. He published a memoir of his experiences as an AIDS patient under a pseudonym9 (he would die from complications of the disease) and worked with the gay rights group Chingusai, which he helped to found, for the remainder of his life. In Lee’s drawing, representations of the letter’s physical qualities stand out, from its uneven tones indicating the paper’s texture to its carefully rendered creases. The letter was once folded and sent by Oh to a close friend. The drawing’s large scale monumentalizes the letter’s intensely personal subject matter as well as the friendship such correspondence represents. When displayed, its monumental scale allows the work to address multiple viewers at once—a public—helping to ensure that Oh’s life and work will in fact not be forgotten.

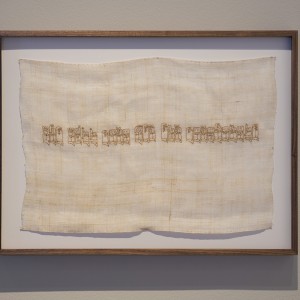

Gold Embroidery on Sambe: Death and Eternity

Since 2017, Lee has been making gold embroidery works on handwoven Korean sambe that evoke notions of mourning and transience. Sambe, a cloth made from hemp, is associated with funerals and death in Korean culture. Before the 1950s, sambe was widely used to make summer clothing for farmers and middle-class families as well as funerary clothing for mourners and the deceased. Since the 1950s, however, as Western-style clothes became more popular after the Korean War, sambe has now been used primarily for burial practices. Sambe is considered appropriate for burial clothing since it is thought to decay more quickly than other fabrics, such as cotton or silk.10 A labor-intensive and highly skilled process, handmade sambe in South Korea is now largely made by a generation of elderly women in rural areas. As more young women from agricultural regions seek higher education and employment in cities, and as the ubiquity of imported, mass-produced sambe makes Korean sambe prohibitively more expensive, the future for Korean-produced sambe seems increasingly unviable.

Like Korean sambe, the gold threads in Lee’s embroidery works connote obsolescence. Lee uses 24 karat gold thread that was produced in the 1910s and early 1920s in Kyoto’s Nishijin district, long renowned for its high-quality textiles. To make this material, strips of pure gold leaf were wrapped around silk thread, a technique that fell into disuse and is now obsolete. There is a limited quantity left in the world of this specific type of Nishijin gold thread. Unlike Korean-produced sambe which is still being produced, though at dwindling rates, at some point the supply of this historical thread will run out.

While a sense of loss—and the anticipation of loss—underlies Lee’s gold embroidery works on sambe, they are also imbued with a sense of veneration. Gold has traditionally been used to signify holiness or purity (among other meanings) in religions such as Christianity and Buddhism.11 In Lee’s hands, the gold thread makes iconic what is embroidered, as in his Untitled (Cover) (2018). The source image for Untitled (Cover) is the cover of a memorial booklet for Oh. In this image, we see a line drawing of two clean-cut men in suits, looking in the same direction. One man places his hand familiarly on the shoulder of another man and seems to move one leg forward to touch the other’s leg. When viewed on the booklet’s cover, next to the title “In memory of Oh Joon-soo,” the image appears to represent Oh and his close involvement with Chingusai, which literally translates to “Between Friends.” In Lee’s embroidery, though, there is no caption to direct a specific interpretation of the image. It becomes more free-floating, a charged image of a gesture of affection between two men, one that oscillates between reading as homosocial and homosexual. Materially recontextualized in gold thread and sambe, the ambiguous image of male intimacy traced in shimmering gold becomes timeless, while its organic hemp support threatens to disintegrate if not cared for under the right conditions.

Collage: Connecting and Reframing

In many of Lee’s works, collage is used to make unexpected connections between disparate figures, places, and histories, relating what is recognizable to what has been obscured to extend visibility to all. A powerful example of his approach to collage can be seen in his pivotal exhibition Garden (2018) at One and J. Gallery, in Seoul.12 The exhibition brought together images and objects associated with two figures who had never met, Joon-soo Oh and British artist and filmmaker Derek Jarman (1942–1994).13 After coming out as HIV positive, Oh faced immense social stigma and died relatively unknown; many of his essays and poems were published posthumously through the efforts of his friends and colleagues. In contrast, Jarman’s avant-garde cinema, which combines representations of queer sexuality with a punk sensibility, were critically well-received during his lifetime and after. Both were committed gay rights activists and died within a few years of each other from AIDS-related illnesses. To create his works for Garden, Lee went to Dungeness in Kent, England, to visit Jarman’s final home and garden, a place dubbed Prospect Cottage. The filmmaker found and purchased this site shortly after learning he was HIV positive; he found deep solace in working on his garden during the last years of his life.14 In Seoul, Lee conducted research into Oh’s life and work at the Korea Queer Archive and spoke with Oh’s friends and colleagues from his time at Chingusai. Throughout Garden, Lee’s arrangements of publications, photographs, personal items, flowers, stones, and soils, collected in two different parts of the world, weave together Jarman’s and Oh’s uneven legacies in a layered remembrance of their parallel struggles and acts of creation and resistance.

Although Lee’s Garden exhibition as a whole could be viewed through the lens of collage, his work Untitled (Table) (2018), presented near its start, can be seen as representative of the show’s premise and his use of the medium. On opposite sides of a square wooden table top, we see an array of objects, including stacked photos of Prospect Cottage and places in Seoul tied to the history of its gay community; a stack of facsimiles of Oh’s daily memos; an issue of Buddy, one of the first gay and lesbian magazines in South Korea, opened to a spread featuring Oh’s obituary; snapshots of Oh in daily life as well as his funeral service; a folder of writings by Oh, opened to two pages of a letter; a copy of Oh’s memoir (under a pen name); and a copy of Oh’s memorial booklet. Down the middle we see a table runner made of sambe, embroidered in gold thread with the repeating motif of a leaf sprig with a heart on top. (The motif derives from a curtain Lee saw at Prospect Cottage, pictured in his print Untitled (Curtain at Prospect Cottage) (2018), included elsewhere in Garden.) On top of and adjacent to the sambe runner, we see rusted chain links from Jarman’s garden and small stones lying in pairs or side-by-side in a group—metaphorical images of the intimate bond between two entities, or a group of entities. An unglazed ceramic work made from California clay mixed with soils from Dungeness and Seoul’s Tapgol and Namsan Parks—storied gay cruising sites that Oh mentions in his writings—sits near the table’s middle, a vessel meant to be filled with a fresh offering of plants when on view. Above the table, suspended on a piece of gold thread is Oh’s gold rosary ring. (Oh, like Jarman, was raised Catholic.)

The emotional gut punch of the installation derives from Oh’s two-page letter on display (one page of which Lee drew for his aforementioned Untitled [Joon-soo Oh’s letter]), in which he speaks of his aching loneliness in relation to his sadness at not having experienced profound romantic love and his fear of not having mattered to anyone. Lee has spoken about using Jarman’s story as a way to introduce larger audiences to Oh’s story,15 though his Garden works, such as Untitled (Table), also bring the two stories together to reframe Oh’s legacy: instead of considering Oh as someone who was largely forgotten, Untitled (Table) shows Oh’s historical significance and how he has continued to matter to people, as evidenced by the publications, memorabilia, and other objects saved by members in his community that were loaned for the show. Just as Jarman coaxed a thriving garden into existence from a rugged landscape, so Lee’s Garden works help to nurture Oh’s own growing legacy.16

If Untitled (Table) brings together objects to connect the legacies of two gay figures, Lee’s Untitled 1, 2, and 3 series (2021) from his exhibition Briefly Gorgeous (2021) at Gallery Hyundai, in Seoul, collages together a more expansive and sprawling history of queer desire and its manifold manifestations, one that spans the past century to the present day. A heterogenous set of images and objects were assembled onto the surfaces of three large wooden panels. They include a photograph of Jarman’s Prospect Cottage; a still from Lee’s three-channel video Garden (2018); a graphite drawing of Andy Warhol’s Hands with Flowers (1957), tonally reversed; a photograph of the Transgender Memorial Garden in St. Louis, Missouri; a graphite drawing of Jean Cocteau’s illustration for Jean Genet’s Querelle de Brest (1947); a photograph of a group of men standing in front of a large banner that reads “WE’RE ASIANS / GAY & PROUD”; a graphite and watercolor drawing of a work from the series For the Records (2013–ongoing) by the New York–based queer women collective called fierce pussy; a graphite drawing of a photograph of James Baldwin; feathers dating from the 1850s; pearls; stones; among many other objects. Taken together, these elements represent the aesthetic discourse of numerous generations of queer cultural producers, tragic consequences of trans- and homophobic violence, as well as grassroots organizing of different groups of queer activists. The insertion of Lee’s graphite drawings of other artists’ works and small prints of his own works into this series indicates the subtle integration of his own presence within this cultural and historical microcosm. If conventionally we are taught to separate “art history” from “world history” as represented by mainstream publications like Artspeak, Lee’s collage series Untitled 1, 2, and 3 tears down such a construct by instantiating that art history is world history.

Video: Desire and Release

Desire, tinged with loss, longing, and eroticism, courses throughout Lee’s most recent series The Heart of A Hand (2023), which is based on the life and works of Singapore-born dancer and choreographer Goh Choo San (1948–1987). Goh trained in ballet starting at young age,17 and upon finishing university, he moved to dance with the Dutch National Ballet. While in the Netherlands, he choreographed a few ballets, which led to a position of resident choreographer and later associate director of the Washington Ballet in Washington D.C. An outside commission by Mikhail Baryshnikov for the American Ballet Theatre resulted in the critically acclaimed ballet Configurations (1981), which led to commissions from other renown dance companies around the world. Although Goh was recognized for his artistic achievements during his lifetime, his sexuality was not publicly mentioned. His longtime partner H. Robert Magee traveled extensively with Goh and was introduced to Goh’s family as his business manager, but their romantic partnership was never discussed. At the height of his career, Goh died from an AIDS-related illness, as had Magee some months before. Lee’s mixed media on goatskin parchment works for this series seem to reference the silence around this core part of Goh’s identity through the blurring out of Goh and other figures, including Magee, in his otherwise precise drawings of archival photos. Coded representations of gay desire appear discreetly on the parchment surfaces: pieces of oak gall from Elysian Park, a gay cruising site in Los Angeles; pearls that evoke drops of semen; watercolor drawings of stones from Prospect Cottage and gay cruising sites in Seoul and Singapore; fragments from poems about desire by gay poets, including Xavier Villaurrutia (1903–1950), Donald Woods (1958–1992), and Samuel Rodríguez (dates unknown),18 some translated into an American Sign Language (ASL) font designed by the gay New York–based artist Martin Wong (who also died of an AIDS-related illness in 1999).

If desire only subtly appears in Lee’s collaged, mixed media works for The Heart of A Hand, it undeniably takes center stage in his video works for the series. The video The Heart of A Hand was made in collaboration with members in Lee’s queer community, including Brussels-based non-binary dancer and choreographer Joshua Serafin, Los Angeles–based director of photography and film editor Nathan Mercury Kim, and Seoul-based transgender composer KIRARA. The video begins with floating hands in the Wong-designed ASL font forming lines from Villaurrutia’s poem “Nocturne” (1938) that speak of a rush of sexual desire brought on by the darkness of night. The rest of the video shows a masterful solo performance by Serafin, lit in dramatic chiaroscuro. Serafin dances using an amalgamation of classical ballet, modern dance, and dance moves that one might see at a night club. The music pulses with the intensity of an EDM track. The source material for this performance—Goh’s choreography for Configurations, set to Samuel Barber’s Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, Op. 38 (1962)—seems faraway. Towards the middle of the performance, Serafin falls to the floor and a light bulb drops down. The music slows down as their body twitches. Then, after a burst of ecstatic dance, the final movement begins: Serafin’s body, now covered in gold paint and glitter, dances languidly and sensuously. They slowly unspool a length of gold thread from their mouth. The video ends with them looking straight into the camera with a smile, and then laughing softly as they walk away. Through its imagery, sequence of movements, and pulsating soundtrack, Lee’s The Heart of A Hand video counters the prim classicism of ballet and the repression of Goh’s homosexuality with an aesthetic vision of struggle, seduction, and release, such as the kind of liberation that one might feel while out dancing in an underground club.

Whereas Lee’s The Heart of A Hand video centers on the narrative journey of a single dancer, his Lazarus video (2023) focuses on the intimacy created through interactions between two bodies. The source materials for this work include Goh’s ballet Unknown Territory (1986) and Brazilian artist José Leonilson (1957–1993)’s Lazaro (1993), a sculpture consisting of two men’s dress shirts sewn together, made shortly before the gay artist passed away from AIDS-related complications. The video begins with floating hands in Wong’s ASL font that spell out lines from Samuel Rodríguez’s poem “Your Denim Shirt” (1998). The poem’s narrator is speaking to a dead lover (“Mi Amor”) who has died of a virus; he is throwing away his lover’s belongings fearing that they might spread the virus, but he is still in love. The music is pensive, paced at a moderate tempo. Then we see a sequence of movements between two men, from close-up shots of their hands touching to different configurations of their bodies rolling, resting, and curling into each other on the floor in a large room. The room is lit by florescent lights in a triangular shape, recalling the triangle in the iconic “Silence=Death” poster (1987) distributed to raise AIDS awareness. About halfway through, we see Lee’s remake of Leonilson’s Lazaro sculpture in sambe on a hanger. The two men don the double-ended sambe shirt and the lighting changes from cool to warm. The music turns more dramatic as the two dance, moving away and towards each other repeatedly, in various configurations, within the physical constraints set up by their shared shirt. At the end, the two take off the shirt and set it respectfully on the ground as the lighting turns cool again. One man places his arm around the shoulders of the other man and together they walk away as the camera fades. The tone of Lazarus is multivalent: while the work mourns loss, especially in connection to AIDS, it also explores the emotional complexity and ambivalence of moving on from such loss. Notably, Lazarus’s narrative is left open-ended, with the suggestion that the Lazaro shirt can be reactivated and thus re-signified, perhaps indefinitely.

Coda

Lee’s artistic practice illuminates networks of care, nurturing them in the production of his series of works. His artworks help to raise the visibility of queer figures and histories that have been overlooked or under-explored. He operates from a place of abundance.19 Images, texts, and objects collected from archives, libraries, collections, historically specific locations, and more, are reproduced and reconfigured into new constellations. Forms regenerate, taking on new lives in new contexts and assemblages. Communities lead to new collaborations, as collaborations lead to new communities. His works set things in motion.

Notes

The author would like to give warm thanks to Kang Seung Lee, Sooyon Lee, Young Chung, and Uday Ram for their generosity in exchanging thoughts about Lee’s works and related matters. She is also grateful to her mother Eun Hee Moon for her translation help and insights into Lee’s works and their Korean cultural context.