JAE HO JUNG

Interview

CV

<Selected Solo Exhibitions>

2017

Heat Island, INDIPRESS, Seoul

2014

Days of Dust, Gallery HYUNDAI, Seoul

2011

Planet, Gallery SOSO, Paju

2009

Father’s Day, Gallery HYUNDAI, Seoul

2007

Ecstatic Architecture, Kwanhoon Gallery, Seoul

2005

Old Apartment Building, Kumho Young Artist Program, Kumho Museum of Art, Seoul

2004

Cheongwoon Civil Apartment Building, Gallery Fish, Seoul

2003

Travel to lncheon, Incheon Shinsegae Gallery, Gallery Fish, Seoul

<Selected Group Exhibitions>

2017

The red brick house, OCI Museum, Seoul

2017

Accidentally, the night again, WUMIN Art Center, Cheongju

2016

Realism, Maison d Ungno Lee, Hong Seoung

2016

Home Ground, Cheongju Museum of Art, Cheongju

2016

Retro Scene, Space K, Seoul

2015

Return Home, KOOKMIN UNIVERSITY Museum, Seoul

2015

Space Life, ILMIN Museum, Seoul

2014

Home, Where the Heart is, Arko Art Center, Seoul

2014

The Relics of Old Seoul, Buk Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul

2014

Parallax View, LIG Art Space, Seoul

2014

The Republic of Apartments, Seoul Museum of History, Seoul

2013

Real Landscape, True Reflection, OCI Museum, Seoul

2012

Urban Promenade, Pohang Museum of Steel Art, Pohang

2011

Busan my city, my strange place, SHINSEGAE Gallery, Busan

2010

Fragmented Paysage, Daegu Culture and Arts Center, Daegu

2010

Between, ONE AND J. Gallery, Seoul

2010

2010 Seoul Archive/ Urban Landscape, Daewoo Securities Yeoksamdong Gallery, Seoul

2010

Now, things that are expressed paintings, GANA Art Gallery, Seoul

<Collections>

National Museum of Contemporary Art

Seoul Museum of Art

Busan Museum of Art

Jeju Museum of Art

Seoul National University Museum of Art

Kumho Museum

Uijae Museum of Korean Art

OCI Museum

Critic 1

Paper-Brush-Ink, Modernity, Body

Kim Hak Lyang (Visual Artist, Independent Curator, Assistant Professor at Dongduk Women’s University)

Planet is a good index of the themes and ideas Jae Ho Jung’s paintings intend to convey and his artistic attitude. Through a rough terrain over which large flakes of snow fall diagonally a steam train is rushing to the right out of the picture plane. This image is borrowed from one of the photographs of Korea after the Liberation, and according to the artist, the steam train is “adrift” in snowy fields. To him an image referring to a specific moment of the past history never dies. It is not something that lived in the past and has been dead for long. Instead, it makes constant appearance before us like a ghost and throws cold water on our/the present’s directions, coordinates, ideologies and desires. Image is history itself and even ourselves: “For me, the image of a steam train running through cold, snowy fields occasions the most severe feeling of solitude. It has a fixed trajectory, but it seems that it will never arrive at its destination. So distant and so nebulous.”

There are two reasons for my recommendation of Jung for the Korea Artist Prize 2018. First, amidst of the high popularity of a kind of mental landscape that stresses arbitrary dismantlement- reconstruction-interpretation in the contemporary Korean painting community, Jung tackles head-on the important points with respect to attitude and ideas. His series of painting projects known as “Apartment”—Cheonguun Simin Apartment (2004), Old Apartment (2005), Ecstatic Architecture (2007) and Heat Island (2017)—makes a detailed exploration of the subjects as if he were a documentary director. His detailed brushwork deals in particular with those old apartment buildings to be torn down due to urban redevelopment or collective residential buildings for urban low-incomers. His aim is not the accurate, photographic representation of the façade of those sceneries but to portray the landscapes as comprehensive environments with their own history and presence or as living breathing organisms. So his apartments are living bodies breathing with us—individuals/groups/ histories—rather than some objects over there. What is also well known together with his ‘Apartment’ series among his works is his series of paintings whose images are indebted to photographs of certain incidents in the modern and contemporary history of Korea that he selected as an archivist—Father’s Day (2009), Planet (2011) and Days of Dust (2014). As mentioned briefly above, in these paintings Jung’s past/image haunts us/the present like a ghost or a fog or repeatedly puts our lives back to ruins. This past/image the painter scoops up from the abyss enables us to manage to meet ourselves hanging on just barely above the water.

Secondly, Jung leads us to look into the reflection on the aesthetics and medium from the context of Korean modern and contemporary art. As well known, most art practices and aesthetics on Korean ink painting in 20th Century have‘t been liberated from the colonized aesthetics from Joseon Art Exhibition under the Japanese occupation or been obsessed with that of the literary painting as a doctrine for the radical recoil. As a result, the ink painting artists of today have to find their way to be free from the colonial aesthetics and ideological nationalism/traditionalism from the ground. We should raise a question if the artist with brush and ink to confront head-on the jarring conditions of the city with new sensibilities, from new critical perspectives and with new insights while still working with traditional painting materials while following the canons and languages of western art instead of our tradition of “Poet- Calligraphy-Painting”.

It might go too far but Jung is the first artist of our contemporaries who goes into the city and the life in it while using the traditional medium like Ungno Lee in 1950s. Ungno Lee, who left tranquil scenary paintings for Joseon Art Exhibition during Japanese occupation, produced improvisational paintings on the vivid daily lives of lower classes in the city from 1945 to the mid-1950s. After the liberation in 1945, Lee was liberated from the classicism or the canon of colonialism and went into the street where the real lives resided in humble but vivid way. To encounter reality and the world with nothing but his or her own bodily senses, Ungno Lee painted the world nothing but his own bodily senses and feeling. Jae Ho Jung has been away from the doctrines of the history and tradition and put himself into the “bodily encounter” with the real lives since he graudated from the university.

Jung undoubtedly stand out in the history of modern and contemporary Korean art—namely in the history of Korean art since Korean literati ink painting the modernization of Korean art gave rise to the reduction of its classical paradigm of literati ink painting that combines text, calligraphy and painting to Western-style visual artistic practices, and when one sets out to find among painters working with paper, brushes and ink those who have felt, experienced, questioned and interpreted his or her body, reality and the world with nothing but his or her own bodily senses, For Jung, all his senses—not only visual sense but also auditory, olfactory, gustatory, tactile sense— from his own body became an artistic medium instead of pursuing freehand painting or thoughts from the heart.

Then artist body becomes a media between the world and art and the modernity of sense and medium begins at this point. This is what the Korean ink painters missed in 20th Century. They seem to come to close to the visual modernity via adopting western art canons at a glance but they never consider the modernity themselves from the perspective of sense, recognition, attitude and body. Since Ungno Lee expand the boundary of Ink Painting with his own spirit to what he saw, listened, smelled, savored, touched without the conventional concept and composition in 1950s, Jae Ho Jung treats all the images produced in the Korean modern history whether they are real landscape or object as the real body. For him, they are not the shadows of the world but also the real body it affects to the world. For Jung, the most essential concept is a kind of “vividness”. This “vividness” or “vivid energy” is born in the relationship between artist’s body and the world. For Jung, to paint is an encounter the world with his own senses as a reality and an attitude to access the light and shadow of life, and even the decision to open up himself to the inner/outer world. (Modernity begins from the body, its senses, and the world interpreted by them. If ink painters can’t realize it, they cannot but escape from the trauma of the distorted modernity. Artists should open his body not to art but to the world.

Translation: Kim Jawoon

Critic 2

The Rusty Reality of the World:

Painting as a Struggle Against Contemporariness

Sim Somi (Independent Curator)

1. Prologue: Note on Anachronistic Painting

Some people might wonder why we should rethink works by Jung Jae Ho at this point. Is it because Jung has documented what has happened in our cities since modernization? Or is it because he has pursued Korean traditional painting which struggles to survive in contemporary art? Neither or both could be a reason. Apartments as subjects and Korean traditional painting have been important features in defining Jung Jae Ho as an artist. However, there are already plenty of artists in the Korean art world raising questions about apartments, architecture, and modernism. Also, he is not the only one who endeavors to retain traditional painting in a modern way. If I had not seen Heat Island1(2017), I too would have had such doubts. I mention this exhibition at the very beginning of this essay because Jung became different after it. As we know, before Heat Island Jung was an ‘apartment artist’; after it, realism appears prominently. This exhibition, Rockets and Monsters (2018)*, solemnly addresses the latter. Since the late 1990s his interest in reality has drawn him to cities and apartments to track fragments of modernism which survive like ruins. He had to undertake all these journeys to arrive at reality.

About this time last year, he was painting buildings. He was painting a protruding façade in detail, even the old stains, dust and dirt, each one with a detail brush. Watching him doggedly painting his subject, I hesitated when it came to deciding how I should perceive his realistic painting. Month after month passed, and I watched him still concentrating on the same piece. I was in trouble. Isn’t his painting overly anachronistic? Continuing to practice realistic painting in an era when representing things as they are is nothing new, apparently indicates a determination to be anti-contemporary and anti-painting. Isn’t he just practicing the grammar of anti-representation which contemporary art has achieved—more faithfully and even, paradoxically, more happily? It may seem difficult to find any connection between Heat Island which depicted shabby apartments in Hong Kong and Rockets and Monsters. However, I will still attempt to link them in terms of their anachronistic features and their pursuit of anti-contemporary performance. It is evident that he has brought to light things overlooked by contemporariness through his ‘overly, excessive painting’.2 In his new work, Jung opposes contemporariness in a broader sense, incorporating temporality, placeness, and the current painting norms.

2. An Exhibition without Apartments: Rockets and Monsters

In the new work, there appear none of the apartments Jung is known for. Instead, it deals with modernist architectures built in central Seoul in the 1960s–70s. It includes film stills, cartoon rockets, advertising images and landscapes of Cheonggye Stream seen from a rooftop on Sewoon Plaza. Some might wonder why his characteristic subjects are missing. However, Jung has approached old apartments not as a subject but as a theme that helps to make sense of the period since the late 2000s. By noting such changes, his work can be divided into two periods. The first period, starting from his solo show in 2001, was a journey during which his interest in cities gradually led him to delve into places such as apartments and buildings. In the second, beginning in 2009, Jung has focused more on the background of the times which such places connote. Meanwhile, a turning point in his practice has recently emerged and this is Heat Islands in 2017. I single out this exhibition as significant since the gap between the two axes of time and place which had been getting slowly closer ‘became none’3 and were ‘patched up’ through painting. If we only examine the title, Rockets and Monsters may appear to have no connection with any of the other exhibitions. However, there are three axes that closely interlock.

First of all, the exhibition is based on a reflection on modernity. Regardless of apartments, buildings, objects, place, and period, there is a consistent axis of time running through his entire practice. Jung repeatedly looks back to the 1960 and 1970s when modernization was happening nationally, not to remember the past but to examine the dilapidated landscape along with the remaining social aspects of the time. Urbanization was a central feature of the country’s drive to achieve rapid modernization, and architecture has been the façade of the era in which such dramatic growth and great leaps forward were proclaimed and flaunted. In his new work, Jung focuses on the social imagination that scientific technology promoted under the flag of ‘modernization of the nation’. Analyzing media such as film, cartoon, and advertisements which were communicating with the public, he investigates the ruins of the collective dream of utopia. The somewhat childish title Rockets and Monsters came from what he learned of the relationship between propagandistic social vehicles and the public of the time.

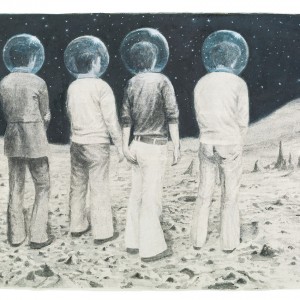

‘Rocket’ and ‘Monster’ are metaphoric references to the illusion of modernity and to its ghost, respectively. According to the artist, the rocket is a “dramatic fictional symbol for an illusion of modernity” and the monster is “an entity expelled from and discarded by the tides of modernization”.4 Nevertheless, in the exhibition, the rocket appears as a physical object carrying materiality rather than as an expression of a dismal ruin. At the center is a lunar module in three dimensions entitled Cast Away (2018). This spacecraft, a colored paper model in a scene rather like a shipwreck, emits smoke through a fog machine. At a glance, the piece could be mistaken for a display in a science museum due to its presentation. The simple shape and texture of this analogue reproduction are the sort of thing likely to be found in a children’s cartoon. On realizing this, Jung consulted a comic book Yocheol The Inventor, which he used to read in his childhood. This book, published in 1975 by a cartoonist Yun Sungyun, mirrors both the social aspects of collective dreams and the illusion of scientific technology at that time. Ruminating on this, Jung examines the gap between propaganda and reality around scientific technology as well as a syndrome of the time when such a hope floated about like some ghost.5

In the cartoon, the rocket launch was not very successful. The protagonist not only fails to perfect his rocket but also many different things: a flying machine; oil extraction from garbage; space food; a time machine. His inventive projects constantly fail. These failures, however, operate as a driving force for imagination and the cartoon continues with the story of each new invention. Jung painted a scene where the rocket actually lands on the moon, unlike the cartoon in which the protagonist’s attempt comically ends up crashing into a stream. Imagining this in a real life, Jung situates the rocket as if it is wrecked. He pictured a rocket roaming and rusting somewhere along the track of history and progress. This is neither a wish for scientific technology nor a realization of imagination. Instead, it resembles the very illusion that the nationallyencouraged science and technology induced in the public. The painting conveys a condition of incompleteness discarded by a society which hurries towards the future. The artist would have wanted to embody an aspect of the time that lost its way, by expressing a lost collective utopia with the image of a wreck.

3. The Three-Dimensional as The Fundamental Quality of a Flat Surface: How Did A Cartoon Rocket Become 3-D?

The artist’s contemplation on modernity began in earnest with Father’s Day in 2009. Since then, until Planet (2011) and Days of Dust (2014), he had persistently collected and painted scenes of the 1960s and 1970s, reflecting on “things floating endlessly, corroded or decayed in the flow of time”6 caused by the rapid economic growth which did not allow a pause to look back. We can find the same rocket in one of the paintings during this period. The rocket that made an emergency landing on the moon in the painting Inventor (2012) appears as a threedimensional object in this exhibition. The rocket is found in three places.7 One is in Cast Away (2012), another is in A Pilot’s Lab regarding the ‘Pilot’ fountain pen factory8, and the last is in A Ball of a Dwarf which portrays a view from the rooftop of Sewoon Plaza. The appearance of the rocket creates a route through the exhibition for the viewer to follow. During a journey from ‘a machine wishing to fly’ to ‘a rocket lab’, there appears ‘a girl dreaming of the promising future’. Then, ‘a rocket which made an emergency landing’ is encountered.9 This composition is in line with Jung’s works depicting scenes from popular films of the time. His blurry paintings reinterpret images from films embodying melodramatic sensitivity: Monster Yonggari (1967); Evil from Space (1967); and Love Me Once Again (1968). A dim afterimage is laid out on paper, consisting of modernity’s emotional pleading intermingled with reality and fiction.

When he planned to make a rocket out of paper, I thought it would be unsuccessful. He cut up some paper and started to build a structure. While his plan was gradually being realized, I noticed his voice was becoming more and more excited, and sounded strange. He even experimented with a cigarette to create smoke from a rocket which made an emergency landing. He did not look at all exhausted despite the heavy workload; rather he seemed to have fun realizing what he had imagined. One month passed, then another and the rocket came to look slightly worn-out and abandoned as if it had physically reacted to its apparent condition as a shipwreck. It’s almost as if the inventor Yocheol is resurrected through the painter Jung Jae Ho. Even though the rocket drops from the sky and crashes into a stream seemingly ending the play, the painting restarts it in the next act. We need to pay attention to the subjectivity of this three-dimensional sculpture. Jung could maximize the materiality of the sculpture and its spatial situation in realizing the rocket. But, why does he stick to the traditional method of painting which applies colors onto paper?

The beginning of his three-dimensional work goes back to 2005 when he examined and painted public apartments. He conceived paper monuments to commemorate old apartments which had disappeared under the rationale of development. In 2005, he made Daegwang Mansion Apartment in relief and Joongsan Pilot Apartment in three dimensions. Since then he has created more: Ahyun Apartment (2006); Monument for Public Apartments (2005); Anam Apartment (2006); Namdaemun Building (2007). These three-dimensional works are monuments to the irony of places from the old era that capitalist logic has neglected and treated as monstrosities. In this exhibition, Cast Away shares the artist’s enthusiasm for the monumental representation of loss and oblivion. All of these were symbols of modernity and yet are now monsters of the old era that will inevitably and gradually disappear.

The way in which Jung Jae Ho creates a three-dimensional object is not very different from that of painting. He paints the skeleton of a building and adds the surface and structural details to it. Cast Away went through a process of making the texture and the shape more sophisticated than an apartment in three dimensions. He cuts hardboard to make interior frames, adds layers of paper for the surface and applies many layers of color to express materiality and to produce fine details. The buildings and the rocket are equally solid whether in two or three dimensions. Interestingly, the solidity of the subjects is founded on these countless layers and the fine details of each brushstroke as well as the whole structure. The threedimensionality of the materialized rocket serves to accentuate the paintwork on every facet. Therefore, we experience and appreciate the rocket by looking from every angle and through the accumulated layers of time as well as peering into the surface, which is not how we see other three-dimensional objects. Circulating around the subject, the viewer gazes at every face as it appears. Seeing it this way, even the dichotomy of being both flat and three-dimensional is easily forgotten. The important point in appreciating artwork is not to clarify the identity of the work as somewhere between a flat surface and three-dimensional, nor to define what the painting is about. What we can find in the relationship between the two lies in the question: “What does Jung seek in his painting so that he can get closer to reality?”

4. Reconstruction of Perspective, A Head-to-Head Contest

It is evident from his perspective that Jung Jae Ho seeks reality. A survey of all his work reveals that one particular viewpoint recurs in his painting. It is frontality. Refusing the perspective which captures an object from a subjective viewpoint, he uses frontal composition in order to face the object as it is. This conveys his determination to depict the original object rather than a view which stems from the painter who tries to grasp it. Jung has persisted with this view which is present in his early work.10 In fact, certain viewpoints are impossible due to the limitation of human sight. In attempting to express architectural façades as absolutely smooth, Jung extends his effort to using photography. He works to capture every detail of enormous objects by thorough inspection of photographs in his studio; something which our eyes simply cannot manage. Starting with overall impressions of the sites, realistic elements are added and even distorted perspective is corrected. This is a way to paint a subject objectively.

An architectural reality is attained not by capturing perspective but from the protruding structure on the surface of the building. What Jung pays attention to is the three-dimensionality of the façade achieved through the structure and surface. At first, such three-dimensionality is emphasized by the structure—beam, wall, window, door—of the building. Then, our attention is drawn to individual and collective descriptions that interpose themselves within the gridlines of the façade. If the gridlines symbolize a modern enterprise and paternal regulation, the details surmounting them undermine the dominant forms and diffuse the power given to the structure into a multitude. This is linked to the flatness of the projected façade appearing subverted in Heat Island. His practice of painting buildings, as in Rockets and Monsters, spans 10 years between Ecstatic Architecture (2007) and Heat Island. As the grids, a symbol of the modern era, overlap with an after-image of that time which seem like ghosts rising from within, the reality of the buildings slowly emerges.

Jung’s gaze was captivated by those buildings as he strolled around Seoul city center. Mostly built between the 1960s and 1970s, the buildings reveal an architectural style, then fashionable, initiated by Sewoon Plaza and Samil Building, two landmarks symbolic of capitalist industrialization. However, what Jung’s paintings contain are not monumental architectures as a representation of the time but banal insignificant buildings encountered in our everyday lives. I would like to share a little behind-the-scenes episode regarding this exhibition. The artist struggled to decide whether to call the exhibition ‘Architecture of Banality’ or ‘Rockets and Monsters’. In fact, the title ‘Architecture of Banality’ could embrace not only his new works but also much of his other work. Ecstatic Architecture sees the artist’s gaze overwhelmed by customary architecture as well as by the wonderment of the subjects. The ‘architecture of banality’ therefore is almost synonymous with ‘ecstatic architecture’.

In the exhibition there are seven buildings with very ordinary titles: Namdaemun-ro Building, Nodeul Town Center, Insadong Building, Cheongpa-ro Building, Hwanam Building, Sogong-ro 99-1, and Sogong-ro 93-1. These titles are either what the buildings are actually called or official addresses. About his interest in buildings, the artist says: “It seems, in a corner of modernization, in architectures, I can see relationships like those between modernist architectures and copies of them, aping or imitating them, illegitimates, hybrids and so on”.11 Even so, he does not inject this thinking into subjects. He restrains his personal impressions so as to express with sophistication and as clearly as he can, reality. What he concentrates on here is the elements of the surface composed of ordinary solid forms. He makes the frameworks of buildings with a lattice of vertical and horizontal grids and goes on to illustrate in fine detail, down to the finishes on paints, tiles, bricks, or stones. The extraordinariness of ordinary architectures eventually comes into view, as a ‘formal condition’ and a ‘social code’ are subtly infused into the materiality of the surface.

5. Battle against Ghosts, Struggle with Materiality

Contemporary architecture has been regularly renewed at the speed of capital. In pursuit of sleek surfaces without frills completely, those architectures hide the uncontrollable private areas. Recent buildings whose surfaces are fully armored with more precise flatness and smooth tones rarely have protrusions in their façades. In comparison, buildings from the 1960s-70s look old-fashioned and shabby. Amplifying the marks of the time which remain on façades as a living element, Jung makes a strong stand against the ghostly nature of things disappearing from real life. This is in opposition even to nostalgia or to ruins which are today’s way to summon the past. This demonstrates the ‘existence’ of the being, rather than showing pity for the disappearance of these traces of the modern era.

The artist’s awareness of such matters is related to the ‘struggle with materiality’ that he has experienced by retaining his identity as a traditional painter. To unveil in minute detail a subject by carefully soaking it into a paper surface might seem to be a tedious battle against ghosts. Jung describes it as “a way to represent the death of materiality”.12 Noticing the predestined ghostly nature of Korean traditional painting, he decided to make the subject inhabit the existing surface as much as possible.13 His attitude reflects his willingness to call on all of reality, like a documentary painter or master artisan, by controlling even his own physical stance to paint the subject objectively. This ‘labor-intensive’ painting, ‘anachronistic’ and ‘old-fashioned’ painting, as mentioned earlier, is the artist’s way of combating the ghostly effect.

Let’s go back to the question at the beginning of this essay: “Is his painting overly anachronistic?” Jung Jae Ho is not interested in atmosphere, aura, mood, or message—things that the painting can change. He also does not appeal to new visual sensations, trendy discourses or contemporariness. Instead, he asks: “What can I do with painting, rather than meditating upon painting itself, in order to question what painting is”.14 His laborintensive painting, painting to faithfully represent the subject, leads to the subject constituting a reality, ultimately the reality. Genuinely having to overcome doubts one after another, from doubts about ‘painting’ and then about ‘painterliness’, he has labored long and hard to reach reality. What he pays attention to is not concept or form but realism, which painting depicts. The more the world is attracted to contemporary art with refined language and forms, the more anachronistic his way of devoting himself to the subject appears.

In this way Jung’s painting evokes not only the places where Georges Perec15 obsessively and minutely depicted so as to resist a loss but also the detailed descriptions that Marcel Proust wrote to restore his childhood memories. His painting that exhaustively lists even the smallest detail before surveying a subject, opposes both a history of the modern era that is like amnesia, and contemporariness whereby the near past disappears as residue. It brings to light a reality marginalized within dominant discourses and simultaneously summons the daily narratives in the surface that were lost to our visual system. By vividly demonstrating the materiality of the surface to his contemporaries who were experiencing a loss of place, the artist determinedly opposes oblivion and the overall syndrome of loss. So, in an anti-contemporary, anti-painterly, anachronistic way, he continues his ‘overly, excessive painting’ to fight against the errors and limits of ‘contemporariness’.

6. A World of Dwarfs and Giants: The Landscape Surrounding Sewoon Plaza

“Now I know this society is a massive monster. It is a massive monster wielding frightening power just as it likes. My younger brother and his friend saw themselves as oil floating on water. Oil and water do not mix. But this metaphor may not be so right. What really frightens me is that, whether or not the two admit it, they are trapped in the rolling mass.”

–Cho Se-Hui, ‘On the Pedestrian Overpass’16

One day in June I went to the rooftop of Sewoon Plaza. I wanted to see a landscape Jung was striving to complete down to the last detail. I gaze at a huge canvas on which he has just started to make a sketch: A Ball of a Dwarf, 2018. It would take at least a month to finish that landscape. Around the same time last year, he was stuck doing another painting of buildings. For three months he grappled with a single piece to slowly add to paper things like stains, dust, rust, dirt, dampness and shadow. If I look back to that time, his current determination might seem less resolute in comparison. A sheet of photo prints is on the floor of his studio. It captures the area around Cheonggye Stream overlooked from Sewoon Plaza. The neighborhood of Jongno street is full of skyscrapers yet the area around Sewoon Plaza is densely populated with low roofs. It is surprising that this kind of area still remains at the heart of an enormous city like Seoul. Over the last fifty years, low-rise houses have been wiped out and replaced by gigantic buildings. The remaining shabby buildings naturally became dwarfs among giants. The low roofs seen from the rooftop of Sewoon Plaza hug the ground like dwarf houses. This is central Seoul in 2018 as seen by Jung Jae Ho.

“From the rooftop, it was obvious at a glance that the old neighboring commercial district has degenerated into a slum. It means that this area was a slum at the time Sewoon Plaza was constructed and is still a slum. By contrast, the plaza’s newly-built pedestrian deck is too neat. I found it amazing. It was a landscape resembling ruins at the heart of the Seoul metropolis.”17

Here is the landscape surrounding Sewoon Plaza that the artist finds surprising: Built in 1967, the shopping mall emerged in Seoul like a monster, advertising development and growth, and has since been recognized as a concrete monument to that time. This building, once called “a monster cutting across the city center”18, dramatically survived the threat of being demolished. An architecture cannot be understood alone and separate from its surroundings. Propagating modernization, Sewoon Plaza stood in conflict with the adjacent slums but now, fifty years later, it is only regarded as an outdated monument. The dwarfs and giants of the past are both subject to the same fate in the fast flow of time. They are all dwarfs eventually, even though they seem to create a contrasting landscape in terms of scale and appearance.

Going up in the lift to the rooftop of Sewoon Plaza, which is open to the public, you see Jongmyo Shrine opposite. In the middle of Seoul, it is hard to find a place where you can see the surroundings without obstruction from just a few floors up. There are some places well-known for their great view of the city: the 33-storey Jongno Tower, the 63-storey 63 Building, the 123-storey Lotte World Tower, and the 68-storey Tower Palace. The cityscape from these super-tall towers is only a forest of buildings. The higher the buildings soar into the sky, the further the dwarf houses recede from human eyes. From the outset, the logic of development does not allow them to be close to high-rise buildings. The landscape Jung paints captures what has been excluded and vanished in a city occupied by capital.

With Sewoon Plaza at the center, the surrounding area is packed with temporary buildings creating a slum-like appearance. Buildings in the area just next to Sewoon Plaza are from 1900 up to the 1970s. The further away buildings are from Sewoon Plaza, the more recent they are, providing a gradually developing landscape. At some distance, Jongno Tower comes into view, and various corporate buildings, hotels and offices stand in line. When Jongno Tower was built in the late 1990s, people were concerned it would be a monstrosity in Jongno Street. On the other hand, they were happy to enjoy the view from the top floor sky lounge on its completion. Human ambivalence is starkly manifest at the moment of destruction or creation. If one stands on the rooftop of Sewoon Plaza, to the left, Gwanghwamun gate comes into view beyond Jongno Tower, and to the right, the scene unfolds toward Dongdaemun shopping center over Gwangjang Market. Ignoring the magnificent panorama between Gwanghwamun gate and Dongdaemun gate, the artist paints the other side—the right side facing Dongdaemun gate. If he had been interested in a contradictory landscape and the spectacle of the city, he would surely have chosen the opposite side, toward Jonggak. However, he intends neither to enjoy a city view nor to represent a spectacle. He only wants to paint as realistically as he can the reality of the subject that has overwhelmed him.

7. Detail and Panorama: Subverting the Politics of Perspective

“On this side there are far more details. I can say, I am working on this piece in order to capture these details—details that seem to have been spat out of the roofs.”19 It was an intuitive response. Upon hearing my question on his choice of a landscape on the right, he said “details” without hesitation. The landscape of the roofs which overwhelmed him is far from sleek flatness.20 It is chaotic, confusing and patchy like a rag. The flatness appears because of the way our visual system works but the world is not at all flat. His three-dimensional work is nothing other than a paradoxical expression to redress a reality that is compressed into flat surfaces. Slates are laid like cloth patches sewn one on top of another; roofs are covered by plastic sheets instead of being repaired; electric wires and piles of scrap metal are tangled together; here and there are run-down machinery and pieces of cast iron. White roofs have been changed to dull and somber brown, and where thin paint has washed away, another color, that of rust, is produced. This is a color hidden from the façade and which has patiently endured the weathering of time. Rusty water from a rusty roof together with leaking rain seep into the interior of the building. The melting away of material nature carries on. The low buildings have travelled the onerous path of the modern era and now expose the difficult times that they fiercely withstood as if spitting their hardships out onto their roofs. This is exactly the face of reality that contemporary time has discarded; a rusty façade that survived in one of the humblest places.

Contemporary cities with a disease of gigantism have concealed the messy truth of reality with their colossal size and dizzying height. A magnificent panorama from these buildings does not include dwarf houses. The contradiction and confrontation in society that A Little Ball Thrown by A Dwarf21 discloses still recur in our reality. In his painting A Ball of a Dwarf, Jung also portrays a landscape of confrontation between regeneration and alienation, concrete and slate, low buildings and tall buildings, dwarfs and giants, and more. However, here his intention is different. He was touched not by a landscape of confrontation but by the way in which both the ordinary buildings and the concrete monument they surround survive together. Sewoon Plaza, whose name means “to draw here the energy of the world”, once attracted people’s attention as an ambitious modern project, but has been relegated to a relic of old times, now merely signifying deterioration and collapse. This symbol of collapse is supported by the rusting dwarf buildings which survive around the mall.

8. A View of a City as Opposed to A Panorama of Capital

Looking down from the rooftop, the artist’s eyes are fixed on the surfaces of buildings as far down as is possible, skipping the glorious vertical distance. His eyes refuse to follow the city’s grand and spectacular panorama; instead his gaze jumps across the distance between a city-scale view and an individual human, the macro and the micro, and arrives at the surface of the subject. By doing this, he undermines the authority of perspective and extensively exposes the subject itself. The reality he pursues is deeply related to the human visual system. One day I had a conversation with Jung about an artist’s panoramic photography. A 19th century panorama introduced by Zachary Formwarlt22 shows a city of that time in ultra-high resolution, and raises the question: “Does this picture convey a city view or a new capitalist system?” This question of what the panorama shows us is reflected in Jung’s practice. He has created many different cityscapes before arriving at a panoramic view with A Ball of a Dwarf. His interest in this subject started with the nighttime view of Seoul from Namsan mountain, presented in his first solo show in 2001. Then, it carried on through landscapes around Inner Circle Expressway, Incheon, Cheonggye Stream23 and Haebangchon. These panoramas embrace the artist’s mixed feelings and affection for the disappearing places and gradually focus more and more on obsessively revealing collective entities that comprise the overall gigantic view.

A Ball of a Dwarf is his first panorama in 13 years. The previous one was A Song for Gangbuk24 in which he depicted the Haebangchon area in 2005. Since then, Jung’s eyes have delved into the inner city, not the outskirts. While the city’s physical appearance was rapidly changing in reality, Jung Jae Ho had been walking through the inner city and had painted citizens apartments as well as the debris of old buildings that have remained from the modern era. During this time, what emerged were old apartments, architecture from the 1960s and 1970s, worn-out objects, and the facades of integrated buildings. His eyes were recording time and space disintegrating and what he was seeing converged in A Ball of a Dwarf. This painting has the structure of a cityscape, but mostly focuses on depicting roofs in detail. The act of adjacent roofs connecting to one another like a rag signifies more than encountering the reality of the other side of the city. It evokes the true nature of the city, the ruins of capital, the fallacy of the panoramic subject, mounting a counterattack on contemporariness and establishing the objecthood of shabby things.

9. Painting Working at Reality, Realism

“I think capitalism might be afraid of painting somehow. The spotless white bear in a Coca Cola TV ad would no longer be attractive to people who believe that real animals’ bodies smell of all sorts and have dirt in their fur.”25

The view overlooking the city informs a complete view of the environment. This perspective leads to the illusion and misapprehension that the main agent (the viewer) is at the center of capital, technology and the dominant ideology. Today, an application like Google Earth offers us a fake experience with a realistic panoramic view of places. Jung Jae Ho’s urban landscape deconstructs bourgeois ideology, which is associated with such a perspective, allowing us to come face to face with its true nature via our senses and the materiality which constitute our reality. His painting removes the authority of the viewer who primarily wishes to look at a subject in the distance. Revealing so much detail, it also frustrates a desire to hold the subject in a comprehensive and sleek impression. His ‘overly, excessive painting’ which the viewer may experience as suffocating, above all, challenges our senses and our perspective on capital which we embody. This style of painting has spread from Incheon to Chenggye Stream, onto old apartments and building facades, passed through Hong Kong, and so reached the center of Seoul.

A Ball of a Dwarf illustrates a reality in which the landscapes of real lives endlessly driven down by the preeminence of growth and development are “sewn together”26 through exhaustive details in the painting. The rocket launched into the sky means not only a collective dream which cannot be mediated in real life but also a ball thrown high in the sky by a dwarf living under one of the lowest roofs in the city. Woven from a giant’s view, a dwarf’s reality, and a monster’s failed flight, how contemporary this landscape is! One might ask: Why has he created the rocket in three dimensions? Is he absorbed by homesickness or nostalgia? Why has he depicted the subject with such explicit details? As someone who has witnessed the process more than once and up close, I only can say this: “Let’s just go in and take in the paintings, what they contain.” The artist’s intention is to rediscover the most diminished value and unearth the reality of the subjects that has been buried by fickle contemporariness in the age of capital and material. His ‘anachronistic painting’ evocatively portrays the realities which survive in the disregarded subjects and consequently subverts the privileged contemporary perspective which appeals to a sense of loss.

Using his intense awareness of real life, Jung Jae Ho defies the fictionality of retro aesthetics which even capitalizes a syndrome of the time -like ruin and loss- and discloses the entire reality concealed beneath the contemporariness. Demonstrating a collective reality affixed to the façade (surface) with paint, he attempts to restore realism into painting: “People do not want to see oil floating in the sea.”27 Like a line in the novel, the painter meticulously explores the shapes, grimy colors and even the stench of oil rolling on the surface that people do not see. Likewise, he resists capitalized views and institutionalized memory to divulge the truth of the subject and works to narrow the gap between reality and painting. He performs his art so earnestly in order to reconnect our perspective and very senses to reality from which we have become detached.

Translation: Shon Seihee