Tae Bum Ha

Interview

CV

2014

<White-Line of Sight>, Seoul Olympic Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

2013

<Dialogic Method – Collaboration Project>, Seoul Art Space Hongeun, Seoul, Korea

<WINDOW>, Space 15th, Seoul, Korea

2012

<White-2012> Art Space Jungmiso, Seoul, Korea

<Major Group Exhibitions>

2014

<Small thinking(is big) of Sculpture>, Art Space Jungmiso, Seoul, Korea

<Photography & Media: 4 AM>, Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

2013

<WHITE>, Shinsegae Gallery, Gwangju, Korea

2012

<2012 SeMa Archive>, Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

<The 12th SongEun Art Awards>, SongEun Art Space, Seoul, Korea

Critic 1

Perceiving Things Metaphorically “Again,”

and Representation Nullifying Manipulative Representation

Sim Sangyong (Professor, Dongdeok Women’s University)

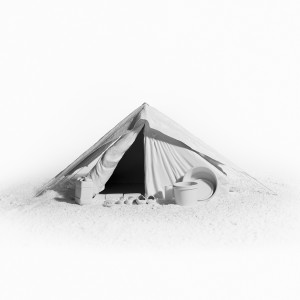

Tae Bum Ha‘s White series, which he began in 2008, focuses on the truth between two different disastrous events and the mechanisms that suppress such truth. The first disaster caused by natural or civilizational factors is extended into the second disaster in the process of being reported. Natural disasters such as typhoons, tsunamis and volcanic eruptions, and civilizational factors such as wars, terrorist attacks and radiation leakages form the first disasters while the second disasters are caused by the suppressive and deceptive attitudes with which the first disasters are treated by the media. Today the media itself tends to be more calamitous than the disastrous events it reports. This is what interests Ha in his White series. The artist believes that the true violence of our era is caused not by the tragic events but by the media’s handling and defining of those events.

Today’s highly advanced media techniques help exploit through sophisticated means the scenes of disasters while suppressing public involvement in such events through coverage overload. It is important, therefore, to minimize the amount of information so as to secure dynamism of perception and interpretation. Accordingly, in Ha’s work, forms are simplified and colors discarded, protecting the subjects from the processes of alteration and transformation that make them more spectacular and consumable.

Ha reorganized the disastrous events in his White series through several phases. The first stage involved collecting photographs of crime scenes, including terrorist incidents, taken by news cameramen, and transforming them into white miniatures made with paper, plastics or other materials. In the next phase he took photos of those miniatures in the same composition as the original news photographs. Colors and many other details were omitted during the process where the original images are represented as white objects. With the process of drastic omission and reorganization the subject of each news photograph was turned into an “event,” not just as it is, but as it is interpreted; that is, “event a” according to the Lacanian expression. The “event a” suspends the manipulative operation of the strategic defensive mechanism hidden inside the original images of the news photographs, nullifying the horrible dialogue that interprets devastation as a variety show.

There exists a sense of peace in the debris of the ruined buildings depicted in the works of Tae Bum Ha —a discrediting of the politics of concealment and consumerism employed by the media and its ritual longing and desire for such. This peace does not allow even the slightest movement, but guides us to a certain “unreality” that the excessive reality intentionally omits—a feeling that the boundary of reality is crossed over, bringing us to experience the Lacanian “gaze.” It leads us to a perception of “another unseeable” reality arriving from beyond the “clearly visible” misery of nature and civilization, and then eventually makes us gaze at this reality by disrupting for a brief moment the consistent perception of “the subject of fixed cogito.”

It is through this gaze that interpretation, distorted by the media, is parted from the real event. In this context, Ha explores how media representation of an event becomes a process of our getting beyond that representation to gaze at the event itself by disclosing media deception, recovering subjective interpretation, and moving towards the perception of the reality lying underneath the event as it is reported.

Strictly speaking, there is no such thing as an objective news report because the report itself is a highly political activity. An event becomes larger or smaller than it is as soon as it is subsumed by the media. Every discourse results from an act of interpretation. Objectivity is nothing but a discourse delivered to hide manipulation.

Tae Bum Ha has consistently focused in his work on the issue of truth suppressed and ensnared by the media. In the artist’s latest works, which include Pieta, Boy and Girl, he explores the wretched dramatization of truths; that is, manipulated “sorrow and compassion.” He uncovers anti-humanism disguised as humanism by taking “a black boy dying with hunger” as an example of an untruth told by relief organizations. These organizations are only a small part of the “huge system of senselessness” that deceives people into believing that donating a couple of coins is enough to relish a prerogative of exemption or acquittal from all kinds of horrible crimes being committed on this planet. “War and terror, all kinds of accidents and disasters, and poverty and alienation are stark realities we face every day, but I often feel that we are left senseless even about the violence taking place right next door because such violence is so familiar to us due to the media” (Tae Bum Ha).

Tae Bum Ha’s world gives me hope, for two reasons. First, he stands on a firm foundation of “meta-perception” directed by the historical, civilizational and social issues of his time. He never turns away; rather, in his work he confronts, through news reports and photographs, the harsh realities of humans in all corners of the global community. From tsunamis in Southeast Asia to the tragic famine in Africa, the artist never turns his back on the misery and pain suffered by humanity today. Directly gazing at humanity from the perspective of the errors of history and the devastation caused by civilization and moving towards love and profound solidarity is, I believe, an urgent need to be met by Korea and Korean art and, in fact, by the entire global community. Is the most Korean the most global? Probably so. But the opposite may also be true. The most global can be the most Korean. The world we live in today has lost its way. Love and unwavering movement towards community and unity form the “meta-map” that will guide the world in the right direction.

Second, Tae Bum Ha has vivid awareness of how the world we live in today has lost its perception of love and community. Our world has lost the direction its gaze for it has lost the right method of directing that gaze. The method was devastated as the world attempted to navigate its way forward amidst the turmoil of modern history and devastation. For art in Korea, the modern history that led it to the art of the Western world also blocked or restricted efforts to share achievements made in the West with regard to artistic perception, interpretation, vocabulary and expression. One problem facing Korean artists even now is that they have limited access to reality, and so they resort to rhetoric, imitation, jealousy, resentment, and frustration. This will continue as long as Korean artists look at the world from borrowed viewpoints or, more precisely, perceive the world, including their own country, from perspectives that position Korea as “other.” Errors made in regard to the method of gazing at subjects easily lead artists to misinterpretation and, eventually, disasters of perception which alienate them for good from the reality they seek. Tae Bum Ha is keenly aware of the problem, probing the media’s processes of manipulating, taming, and enslaving viewers via biases and politically charged frameworks. If I have Ha’s intention correct, his work represents quite an achievement because it uniquely scrutinizes these prejudices, giving us desperately needed alternatives for the fraught times in which we live.

Critic 2

Realism in the Photography of Tae Bum Ha

Soon Young Park (Curator of Seoul Museum of Art)

There are two ways we face the world in our everyday lives. One is to experience it firsthand and the other is to receive the information that has been offered to us. The former is direct with space and time being integral elements while the latter is indirect where information different from reality can also be accepted. As contemporary society is intricately systemized and furtively structuralized, we prefer to rely on information to live in this world. The reason for this is because it is simply much easier. Of course, at times we adopt a way of experiencing the world, but it is too much trouble that we do it when something happens beyond our control or, on the contrary, on our leisure time. Such method could be explained with labor and hobby. In opposition to this, we may receive information through news and books, though it could be less realistic and pleasurable.1)

Nowadays news headlines include one or two big events without exception. News is one of the most effective ways to spread information with bold headlines and images. For this reason visual information can be delivered much faster than any other information and can be recognized at a glance. A news headline may act more like visual information than text information. Walter Benjamin clarified this way of conveying events as the following. According to him, narrative art that passes on information came to an end with the advent of the newspaper. And newspaper, as the representative medium of industrial and civil society, brought new modes of communication apart from ‘experience,’ ‘advice,’ and ‘wisdom’. Benjamin regulated that “this new mode of communication is information.” He determined that the principles of journalistic information are “freshness of the news, brevity, comprehensibility, and, above all, a lack of mutual connection among each news item”.2) Following this, information carried out by news articles thus aims to briefly relate an event which we use to face and grasp the world. This is one of the features of structuralized contemporary society and is not an individual matter. It is difficult and perhaps impossible for an individual to go against it. The main subject of Tae Bum Ha’s work is the criticism of the media. He has primarily addressed news as the medium but does not intend any negative connotations. With this being the case, we have to approach his work from the perspective of a social movement, not art. In the form of visual art, Ha intends ‘to disclose as they are’, the attitude and method in which the society as a carrier of information and an individual as a recipient of information, harness the media.

If we are to accept it in the way we receive the news, then his representations may be clear and immediate enough to recognize at a glance. Alternatively however, this clarity and immediacy entangle our thoughts and we wind up making an effort to sense something else. When representing something, he tends to clarify it enough so that it becomes recognizable to us. What is intriguing is how he destroys this clarity with another form of clarity. Since his early working stage, his concerns have shifted from invisible things such as light, air, and electricity to visible yet invisible things such as garbage cans, benches, stairs, and drains. It then switched to the criticism of media addressing social issues. From here on, let’s examine this process.

Born in 1974, Tae Bum Ha studied sculpture at Chung-Ang University where he also received his MFA degrees. He wrote a thesis titled, A study on Work Production Based on Invisible Phenomena for his master’s degree and won an award for excellence at the Joong-Ang Fine Arts Competition in 2001, a considerably prestigious art exhibition. The following year he unexpectedly left to study in Germany and returned to Korea eight years later in 2010 after completing a master’s course in sculpture at the Stuttgart State Academy of Art and Design. I first met him in September 2010, not long after he came back from Germany. At that time he had been selected to be sponsored by the Seoul Museum of Art’s Emerging Artist Support Program in preparation for his solo show. Back then I was the curator in charge of the program. Afterwards, he was selected as one of the resident artists for SeMA Nanji Residency, where I was also in charge of the artist-in-residence program. It was in such way that we managed to build a lasting relationship. After his return to Korea, he came into the spotlight of the Korean art scene with his White series. Despite having majored in sculpture, this series mainly consists of photographs. He primarily dealt with photography around 2007, when he studied in Germany.

Let’s first examine Ich Sehe was, was du night siehst, a series that preceded White. As it could be noted from his master’s degree thesis, he was very interested in the means to unveil the invisible. The subject matter of this series included air, electricity, and so on. He maintained this interest in Germany where he developed the yearning to express the invisible in terms of the form and content. Just as most strangers in foreign countries do, discrimination, disregard, and a sense of shame became the momentum for him to turn his attention to more underlying concepts. He later asked himself “Why was I interested in the invisible?” This shift in his attention formed an important pillar of his work. He deepened his anxiety on the concept of existence, reflecting on his undersized existence like an invisible being. He turned his eye to the objects he considered as insignificant as himself such as benches, garbage cans, and other things that seem invisible despite their visibility as they are only sought after when needed. He conceived a way to turn them into main characters. After making them meticulously small in size he placed them in relatively rough urban settings. Even the rust on the miniatures was reproduced to resemble their actual sizes in photographs, allowing them to recover a sense of existence where they could play leading role instead of remaining as backdrop. Things visible from another perspective, namely backgrounds, objects, and places, have a sense of presence. This is the method he has chosen to capture things overlooked in reality and also the reason why he has adopted photography as his main medium. He maintained his interest by utilizing this new and expressive method and photographic medium, connecting his consideration of an ambiguous sense of existence to himself. He held his solo show titled, Ich Sehe was, was du night siehst at the Korean Cultural Center in Germany in 2008. The title in German translates to “I see a thing you cannot see” in English, but rephrased according to his intention, it is “I see with interest a thing you pay no attention.” Aside from its meaning, this is also known as a children’s game similar to Twenty Questions in which one poses a chain of questions. The way this game works seems to be in the same context as his working method in presenting presence to objects that resemble him. Afterwards, there was something that diverted his attention and then he began the White series.

It was not easy for the artist to feel sympathetic about the terrorist attacks he read in the news while he was in Europe because he thought those attacks were unjustifiable actions. Such terrorist attacks might have stemmed from a political issue or an individual’s sense of loss for his family. In a sense, a terrorist attack can be seen as something committed not by an attacker but by a victim.3) Cause and effect might occur at the same time and an effect may influence the cause. There is certainly a user and a victim of violence, and the role and nature of the two are often switched around. This is because their role and nature vary according to a community’s power or position toward violence although both terror and violence always involve sacrifice.4) There lies a point that Ha focuses on. The inevitable ‘ambivalence’ of the incident; this is one of the subjects in his White series. He highlighted his attitude and interest toward social issues when he felt daunted by the change in his surroundings and discovered that such interest was in a third-person perspective. In other words, it is none of his business. He mentioned that “I thought about how I judged the terrorist attack while watching the news and it was apart from a single perspective that the news intended to deliver. When I tried to express an event from diverse perspectives, I thought that I was also consuming its images as an onlooker.” This further extends to the thought that such an attitude is universal among all contemporary society and people. In his opinion, the reason why an individual or contemporary society despises another is due to the fact that we all believe it is none of our businesses. He excluded color5), a representative sensuous medium to reveal his indifference.6) The White series is in the same context as his previous series in which he employed optical illusions deriving from the flattening of objects and scenes and used photographs to make them look different from reality.

But this remarkably differs in terms of color and content. He embarked on this series in Germany but he became more aggressive in addressing the subject of indifference in Tragedy in Yongsan (2010) dealing with the Yongsan Disaster. Such being the case, in order for indifference to be established, the one who shows indifference toward an incident must be from the community where the incident occurred.

The Yongsan Disaster broke out in January 2009 less than a year after Namdaemun collapsed in fire. It was a terrible disaster that occurred just 25 hours after the tenants took over a shopping district building for a sit-in demonstration. The government sent a SWAT team which carries out anti-terrorist operation to shut down the demonstration of ordinary people who were merely crying out for survival. The police did not assume any criminal responsibility. Rather, surviving protesters and employees of service businesses were indicted. The fact that the government made attempts to manipulate public opinion and tried to divert public concerns was brought to light but ultimately did not affect the results of the trials. No one seemed to care for the nature of the incident, contending that the disaster was caused by an excessive use of force by violent protesting. Despite the comment that the nature of the disaster lay in the structural problem of the new town construction, the state authority applied the Special Act on Urban Improvement Promotion to Yongsan District 4 which shifted responsibility of the disaster to the unlawful and violent demonstrations. The public was reluctant to deplore the deaths of the victims out of concern that the new town development might stop. In this regard, a sociologist Chang Yoon Ju mentioned that “Power removed Yongsan Disaster and the public avoided it”.7) He applied the term homo sacer to the Yongsan Disaster, a phrase coined by Giorgio Agamben to account for politics and power. Homo sacer refers to an individual labeled as a criminal by a power group. This person could be killed, without the killer being punished. “Even if an ordinary person kills one who is considered a sacred man, he will not be condemned for homicide”.8) Just as Jews imprisoned in the Nazi concentration camps were the homo sacer to Agamben, victims of the Yongsan Disaster and tenants who claimed the minimum rights for living, standing on the edge of a precipice, were the homo sacer. Is this a contradiction of democracy? As a method of exercising one’s power, a person of authority elected by the people as their representative, labels people in opposition as the homo sacer to justify his or her action. The homo sacers of the Yongsan Disaster were burnt to death but no men of power paid for their crimes and the general public remained as spectators. Six years had passed since the disaster. There’s just a parking lot left on the spot of the disaster as if nothing perilous had happened amidst the public’s indifference. As mentioned above and as Tae Bum Ha stated before, the criticism on the media is not merely for finding fault in it. From his White series, we can immediately infer that those are meant to reenact the incidents.

Only the viewers with prior knowledge of the incidents could instantly catch this. Next, they could learn that these are actually reenactment of photographs from the media and that these exude static and dull atmosphere. The photographs featuring terrorist attacks in Pakistan, Bagdad, Yemen, Norway, natural disasters such as the tsunami in Japan and earthquakes in Indonesia, the Yeonpyeongdo bombardments, and urban redevelopment sites, are ultimately to criticize the media so the gruesome sights captured in the photographs are not important to the artist. If he sought to recreate particular events, a moral issue may come up or he may be criticized for adopting others’ tragedies for his own purposes and distorting the facts. This does not benefit him as the effects of the actual incidents overpower his expression of representation. In addition, he may fall into aesthetic consumerism.9) He assures us that “What I address is not concrete incidents but press media.” Through photography, he attempts to capture his attitude of viewing such incidents, the fact that others also interpret things like he does, and the paradoxical fact that this is not revealed. Thus the more horrible an incident is and the more explicitly one discloses death, the harder the member of another community with indirect relation to the incident, makes effort to treat the incident as the affairs of others. The media is well aware of this tendency and thus makes further efforts to maximize these horrendous sights. The artist has selected ‘white’ to symbolize this fact. White represents another person’s perspective toward an incident and the concept of a social structure that makes us view it in such a way. Then why did he choose photography as a medium, going through the process of constructing the scenes captured in news photographs into three-dimensional images?

Photographs document things based on reality while a camera is a device to fix things with images through the use of light. As a means for objective regeneration by nature, a photograph connotes the fact that an object exists. Photography’s ability to record things derives from its substantiality which stems from our solid faith in photography. The features of photography could be divided into three main properties. First, photography has ‘reality’ in that it documents things. A photographic capture is made in one fleeting moment, displaying accurate vividness, and has mechanical reality with a natural tone. It also has the ‘sense of site’. Unlike other methods of expression and conception, a photograph can be made only on the site. That is, the process of creating a photograph starts as soon as one captures a site. Lastly, photography has ‘contingency’.

The American art historian, Michael Fried asserted that “a photographer does not accurately know what he or she took before it is developed,”10) while Winogrand stated, “I take pictures to see what that thing looks like in photograph”. The most prominent property out of these three characteristics of photography is ‘reality’; however this makes it much easier for distorting the facts. A press photographer who captured the last scene of a Vietcong execution confessed that photography is half-truth.

Similarly, an American documentary photographer Lewis Hine commented that “While photographs do not lie, but liars may take photograph.” And yet, we do not need to see photography in the negative way, since art also owes itself to this paradox. Reality is destroyed by reality, leading to the possible acquisition of expressiveness.

The characteristics of photography such as being a realistic, accurate, and objective record of events may be used in a negative way, but generally encloses the value of realism. The process of photography includes an appearance of things, recalling their forms, recognition of their images, and seeing their formal images after this process. Nevertheless, the last phase depends on the intervention of the artist. Artists have exploited photographs to express their creative imagination instead of the phase of their involvement after understanding this process of photography. In the past, photography was merely used to capture what one wanted to see and, as a distinguished writer at the time commented, “there was no indigenous ways to view photographs”. However, photography is now regarded as a medium of subjective expression with its ability to destroy reality, an elemental paradox of photography. Moreover, a reversal has occurred as artists are now encouraged to intervene in the photographic process due to the advancement in digital photography. This requires that the approaches, interpretations, and usage of photographs to be diversified. Above all, we have to understand that the process of photography starts from an artist’s involvement, not from any object, the vividness, an attribute of photography, may destroy other vividness11), and that photography is a proper medium for the world’s uncertainty (ambivalence) through these two reasons. It is for these reasons Ha chose photography as his primary medium. Thomas Demand (1964- ) is a photographer whose works are in resemblance with Tae Bum Ha’s works. Ha’s White series is often associated with Demand’s works due to their formal similarity. One can better understand the features and meaning of the White series by examining the similarities and contrasts between the two. Similarities could be found in the production process. First, the two artists both select images from the mass media such as newspapers and the Internet and make them into three-dimensional objects which they then take pictures of. Second, their works have specific referent and bears the features of press photographs. Third, they are also identical in that the end results of their work are photographs. When seeing them for the first time, the viewers witness their works in ordinary way but after noticing some clues, they realize the scenes are reconstructed. However, the critical difference in their works could be found in how Demand deals with an incident itself while Ha deals with the media that addresses the incidents. Michael Fried commented on Demand that “his art does not appeal to viewers and does not provide any opportunity for empathy. He gets rid of all room for imagination in the scenes he presents. This is just ‘alienated looking’”.12)

This comment is one of the most common criticisms on his photographs. Fried also defines Demands’ photographs as being a representation of what is intended but they “are thoroughly empty places and things in which traces are systematically removed rather than being physically reconstructed models of places and things with cardboard”. 13) From here on, let us discuss Ha’s photographs in comparison with the works of Demand. In terms of how he is able to hold a viewer’s gaze, as Ha’s photographs already include the viewer’s perspective, there is no need to appeal to the viewers. As his photographs also hold emotion and empathy, something analogous to the state of cathartic emotion on the stage of a play, they arouse a rather extreme feeling of empathy. While Demand’s photographs are ‘alienated looking’, Ha’s photos could be described as ‘haptic looking’ as he relies on veiling a scene with a gaze. Although his photos are similar to Demand’s in how they represent the inherent intention in photographs and the process of removing dots and traces, but Ha intends to represent the intention of the society and the public. What he removes are the insignificant things that are difficult for viewers to capture as well as the parts that disturb our concentration. In other words, they can be described as objects that are uncatchable when veiled in white or by the contours of things. Demand and Ha also acquire different things from the removal. Demand gets rid of the evidence and trace of men’s to express empty places and objects whereas ‘removal’ actually means ‘veiling’ for Ha. In this way, his White series could be described as ‘haptic looking’ and ‘veiling.’ These two characteristics play significant role in comprehending his work even though I set them in a contrived way by comparing them with the works of Demand. Thus further analysis of these factors is necessary.

The press photographs that Ha deals with are kind of images and they may either consist of a world inside the images where things exist or a world outside the images from which the viewers see the images. In other words, one is the place where an incident occurs and those being seen exist while the other is the world in which we belong to and those seeing exist. In terms of time, the former belongs to the past while the latter belongs to the present. It is important here that the ground to distinguish one from the other disproves that those two worlds are homogenous. If an image is to acquire meaning, the interior and exterior worlds have to be homogenous. This may be a condition in which the interior world has an effect on the external world. On the contrary, the exterior world may affect the interior world by, for instance, giving a title to an image or intentionally placing it in a different context. The present may influence the past in such a way. If this is the case, let us analyze how these two worlds influence one other. An influence here can be seen as a reaction where one has a direct effect on the other through the sensory system. As a result, we may consider some incidents to be terrible, tragic, and unbecoming. One also has an indirect effect on the other through the cerebral system. The latter is firmly anchored in the principle of the Five Ws and One H. Six questions of who, what, where, when, why, and how are asked at the same time but time is required for the answers to come. News articles that account for the photographs can confirm the answers to such questions.

The two reactions are primary responses that arise superficially. However, the important response exists elsewhere. This is inextricably bound up with the precondition of news photographs. The individual who encounters the image perceives the fact that he or she is outside the place and time the incident took place. This is a reaction that arises much earlier than any from the senses and the cerebral system. As this is an elemental reaction that encompasses all reactions, it takes on the trait, opposite of an attitude towards incidents. This may be ‘a feeling of relief.’ Appreciating the fact that we were not in the incident, and instead we react to it by shuddering. While it is possible that we too might one day become involved in an incident where we live, we can be sympathetic due to the fact that we are not the victims of this particular one. Georg Simmel pointed out that we defend our mentality from the external stimuli that are constantly being generated in an urban setting, something that consequently results in our indifference toward such stimuli. Walter Benjamin gives his analysis of the nature of the newspaper and the way humans sympathize with the news as the following: “Man’s inner concerns do not have their issueless private character by nature. They do so only when he is increasingly unable to assimilate the data of the world around him. Newspapers constitute one of many types of evidence of such an inability. If it were the intention of the press to have the reader assimilates the information it supplies as part of his own experience, it would not achieve its purpose. But its intention is just the opposite, and it is achieved: to isolate what happens from the realm in which it could affect the experience of the reader”.14) A newspaper may assume an important role in running and maintaining the systems of contemporary society but the reason why a newspaper is allowed to fill such a role perhaps results from human instincts. Although Ha’s White series has been derived from his attitude towards society, he has captured some hypocrisy in moral goodness and sympathy. It is not the ‘alienated looking’ but ‘haptic looking,’ a way of veiling images with a gaze.

The white he has chosen is meant to concretize his act of seeing from an onlooker’s point of view. A scene is covered with white as far as his gaze reaches. Many essays on his White series, however, explain that this color is a result of “removing” colors: “removing or refining all colors with white” (Ji Hye Kim); “a simplification of form, erasing of colors, and adjustment of events” (Na Young Jung); and “alienation caused from a bleached reality”. As his intention was to get rid of colors, it is perhaps unimportant whether he was coloring or decoloring. Nonetheless, decoloring literally means to exclude color while coloring means to do away with existing color. While de-coloring is a way to objectify and see an event, coloring is a way of veiling an event with white to protect oneself from an external stimulus as if shrouding the body. If he intends to represent an incident itself, it can be interpreted as “decoloring” but if he intends to represent the media’s duplicity and the public’s indifference, it could be properly interpreted as “coloring”. In other words, photographs used in mass media have become more provocative and violent because they are indifferent to incidents. We shudder at such incidents because we are also indifferent to them.

The artist shrouds such incidents with white to express this paradox but this is not all he intended to portray. What he represents is a gaze veiling an incident but what we really have to discover in this shrouded scene is our underlying ethical consciousness. This is not like a sense of morality based on which we discern good from evil when referring to indifference. An optimistic nervous system works as an instinct to maintain life. We see such horrible incidents nonchalantly in order to become accustomed to them, not having been accustomed to them and we want to see them indifferently not having been dull to such incidents.

The meaning of the color white expands to the domains of video and sculpture. Ha produced and released Playing War Games, Dance on the City, and Bombing over a course of two years from 2011. One features a scene of an airsoft gun being fired at a building made of paper, the other features a dancer dancing in a cluster of paper houses, and the last one is an animation displaying a shower of bombs. While the photographic works show re-photographed images of precisely represented scenes, the video work draws attention to movements by paring down forms. Although this is not a depiction of a specific event, it reminds us of an actual scene we have seen somewhere before. These works represent visible violence in contemporary society very pleasantly at times in an aesthetic and lyrical atmosphere. Despite its actual meaning, violence here takes on an opposite effect, thus leading them to feel more realistic. When a napalm bomb explodes in Good Morning, Vietnam (1987) starring Robin Williams, What a Wonderful World by Louis Armstrong is played in the background. It can be regarded as an ironic portrayal, but it’s the fact from actual incidents taking place in the contemporary society. Afterwards, the White series was portrayed in sculpture and displayed at his 2014 solo show, Line of Sight. Ha took the subject matter of his sculptures from images printed on the promotional materials of different relief organizations. As in his previous series, he addressed images as his medium but this time he did so in sculptures and reliefs. Unlike his previous works, figures are the center of attention in this series. It is in a sense, quite natural because the figures often come to the forefront in the promotional materials of the relief organizations. It is noticeable that he selected sculpture as a medium. Relief organizations have often placed figures at the center to evoke pity and sympathy and appeal to our emotions. The artist pays attention to the fact that the figures may not know that their images are used in such way. “A scrawny little African child is implanted in our memories as a symbol of starvation and as an image symbolizing the reality of Africa. However, no one shows interest on who really he is and what has become of him. The child has been left as a symbol to spur our sorrow and pity”. (From the Artist Statement) A monument is usually posthumously produced to pay a tribute to someone. Of course, some do not fulfill such role but most monuments follow this by nature. Ha considered how the images released by relief groups have a property identical to that of a monument and produced them in sculpture. It is important to keep in mind that he has no intention of renouncing such relief organizations and their contributions as he does not mean to portray them negatively in his criticism of the media. He is interested only in a way of exposing the media and a proper method of representing an image just as it is. We can confirm the fact that such images are represented “very emotionally rather than to convey objective facts, stimulating general interests” both in works in the form of reliefs and works in which headlines of news articles are set in the form of wall texts.

Tae Bum Ha reveals the hypocritical reality in the relationship between the society and the individual through his criticism of the media whose objective is to provide information. This is indifference based on homogeneity. This attitude is the ‘fact’ he has unveiled in the way of destroying reality (implanted and composed) by harnessing the reality (faith) of photography. In other words, the reality we discover in his work is the one of indifference, but this attitude carries significance from two perspectives. It could be described as an ethical attitude that acts as an instinct or a will to live as a member of a community from a social standpoint and also as an aesthetic attitude that seeks beauty from an emotional standpoint.