Back Seung Woo

Interview

CV

2015

Walking on the Line, Centre A, Vancouver, Canada

Photographs 2001-2015 by Seung Woo Back, Goeun Museum of Photography, Busan, Korea

2012

Gaps, Unrealistic Generals, Gana Art Center, Seoul, Korea

Memento, Doosan Gallery New York, New York, U.S.A

2011

Deferred Judgement, Art Sonje Center, Seoul, Korea

Blow Up, Misashin Gallery, Tokyo, Japan

2010

<Utopia / Blow Up>, Ilwoo Space, Seoul, Korea

2009

Revised Ideal, Gana Art New York, New York, U.S.A.

2007

Real World, Insa Art Space, Seoul, Korea

Real World, Foil Gallery, Tokyo, Japan

2006

Blow up, Gana Beaubourg Gallery, Paris, France

<SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS>

2015

The Flaming of Seoul, 63 Sky art, Seoul, Korea

Cross Vancouver, Cross Gaze, 2014-2016 Vancouver, Vancouver, Canada

Dislocation, Smith college Museum of Art, MA, USA

Seoul vite vite, Lille 3000, Lille, France

Lies of Lies, Huis met de Hoofden, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Lies of Lies, Total Museum of Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea

Uproarious, Heated, Inundated, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea

North Korean Perspectives, Drent Museum, Assen, Netherlands

North Korean Perspectives, Museum of Contemporary Chicago, Chicago, USA

2014

2014 Real DMZ Project, The border areas near DMZ in Cheorwon, Gangwon-do, Korea

Open Borders / Crossroads Vancouver, Vancouver biennale, Vancouver, Canada

art:gwangju:14 Special Thematic Exhibition, KDJ Convention Center, Gwangju, Korea

SEMI CLOSE UP, 149-11 Donggyo-dong, Seoul, Korea

Photography and Media – 4:00 AM, Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

Five Views of the Korean Peninsula, noorderlicht gallery, Groningen, Netherlands

Art Plat Form, Art Stage Singapore, Singapore, Singapore

2013

Photography and Society – reflecting on the society, Daejeon Museum of Art, Daejeon, Korea

Relativity in City, Total Museum of Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea

Birth of a Museum: The MMCA Construction Archive Project, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea

AIR 3331 × MIK: Made in Kanda, Art Chiyoda 3331, Tokyo, Japan

Real DMZ Project-From the North, Art Sonje Center, Seoul, Korea

2012

Being Political Popular: Art at the Intersection of Popular Culture and Democracy Movements in South Korea, 1980-2010, UCI Museum, Irvine,CA, U.S.A

Garden of learning, Busan Biennale, Busan, Korea

The Magic of Photography, Daegu Photo Biennale, Daegu, Korea

Re-Opening DOOSAN Gallery Seoul, DOOSAN Gallery, Seoul, Korea

2011

2011 Seoul Photo Festival, Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

the 8th Juan Media Festival 2011, Juan station Square, Incheon, Korea

2010

Phos+Graphos, Gana Art Center, Seoul, Korea

Dreamland, Pompidou Center, Paris, France

Chaotic Harmony, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, Santa Barbara, U.S.A.

archiTECHtonica, CU Art Museum, Colorado, U.S.A.

The View of Korean Contemporary Photography,

National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts, Taiwan.

2009

Chaotic Harmony, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, U.S.A.

Mexico Biennial of Photography, The Centro de la Imagen, Mexico City, Mexico

Magic Moment (Korean Contemporary Art Exhibition), Hanover, Germany

What is Real? Gana Art Center, Seoul, Korea

Double Fantasy, Marugame Genichiro Inokuma of Contemporary Art, Marugame City, Japan

Platform 2009, KIMUSA, Seoul, Korea

Photography Now: China, Japan and Korea, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, U.S.A.

2008

39(2), Art sonje Center, Seoul, Korea

The Bridge, Gana Art Center, Seoul, Korea

The Roots & Being now, Soheon Contemporary, Daegu, Korea

Landscape and imagination, Aram Museum, Goyang, Korea

See it, Bukchon Museum, Seoul, Korea

Image in Contrast, Trunk Gallery, Seoul, Korea

Photo on Photography, Kumho Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

Critic 1

Kim Inseon (CEO, Space Willing N Dealing)

How much power does a photographer have to overcome the limitations that inevitably arise from revealing the gap between the live phenomenon and the still image that is captured by the camera? Every photographic image is a complete abstraction, but it is still based in reality, assuming that the photographed object or event actually exists (or existed). Issues related to this duality have persistently dogged photographers from the beginning. Back Seungwoo is thoroughly aware of these characteristics and limitations that are inherent in the medium of photography. In fact, Back’s strategy is to proactively utilize such limitations, thereby exposing and even emphasizing them. His work also transcends limits, in that it does not end at the moment that he presses the shutter.

Today, every person is inundated with images on a daily basis, and abstruse concepts like “manipulation,” “virtuality,” and “unreality” have become commonplace. In such world, it seems insufficient to regard Back’s works simply as photographs, i.e., as products of a certain medium. Considering his process, it is obvious that his approach varies considerably from the numerous artists who attempt to use photographs to pry open the gaps between reality and imagery. His mode of dealing with certain objects as visual art does not stop after he has shot them with his camera, nor even after he has examined the printed images. When considering the photographic medium, the process of creative development coincides with the process of producing the conceptual layers of the works. But Back is more interested in using the gaps between the reality and fiction of an image to reveal the actual process of production. Moreover, he pays particular attention to the intervention of external elements in this process, and to the attitude and response of the viewers to the results.

These concerns are abundantly clear in Back’s Utopia series, which he first presented in the 2011 exhibition Deferred Judgement at Art Sonje Center. One of the works from that exhibition was Utopia #32, wherein Back divided a single digital image into thirteen parts, had each of the thirteen parts printed in a different country, and then re-assembled the results into a single image. The original image was a promotional photo from North Korea, which Back digitized and restructured. When sending out the sections of the photo to the different countries for printing, he specified that they all be printed according to the same settings and on the same type of paper. However, the final prints that he received showed many differences in color tone, some subtle and some very obvious. After receiving all thirteen images, Back assembled them back into one image, which was then exhibited as a large photographic work.

Looking at the final photo, viewers realize the errors that can result from supposedly “objective” data. Although Back specified the exact parameters and details of the development process, the gaps emerged, with no possibility of further arrangement. These gaps exemplify the countless traces of errors and individual differences that inevitably characterize the supposedly “mechanical” medium of photography. By forcing viewers to confront such differences, he alludes to the ways in which our cognitive system can produce divergent images from the same quantitative data, depending on the context. At the same time, he provides a compelling reminder that such discrepancies are inherent to every organization, group, or system.

By revealing the errors that emerge from precise information, Back Seungwoo discloses the fragility and peril of a system. He further developed this concept in his Blow Up series, seeking to actively shift individual perspectives by taking an even more meticulous approach. In 2002, Back had a chance to visit North Korea. He was allowed to take photographs, but the entire process was heavily censored. For example, he was told exactly what angle he could photograph a scene from, and if he veered from that angle in the slightest, the censors instantly deleted or destroyed the photo. After returning to South Korea, Back was very disappointed with his photos from the trip. Dismissing them as mundane and tedious landscapes, he put the photos away and forgot about them for a few years. But then one day, looking at shots of North Korea taken by another foreign photographer, he was struck by some intriguing similarities. For example, he noticed that the same person appeared in both sets of photographs, looking almost identical in the two shots. Inspired by this discovery, he began to look more closely at his forgotten North Korea photos, and other accidental elements began to emerge, which he then took to be the fundamental components of the landscape. Hence, this series may be seen as the point in which Back began to consciously deal with objects via the medium of photography, or perhaps as the moment that his photography was freed from the confines of the specific time or space that the images were captured. In addition, Back’s experience of taking photos in North Korea opened his eyes to the helplessness that one feels when under the thumb of a totalitarian state that controls every movement. Although the photos were the result of the physical responses of Back’s own eyes and body, the state itself actually controlled the entire process, thus assuming the role of creator and rendering the artist as a passive instrument. This unique experience led Back to pursue future projects that involved images that he himself did not actually photograph. Hence, the Blow Up series shows the visual sequence of an artist seeking to eschew the surveillance and control of the ruling power. Of course, given the peculiar condition of the division between North and South Korea, this series is generally interpreted in a political context. The artist, however, does not consider this series to be any kind of political statement. Such interruption of political circumstances and perspectives thereby demonstrates the social “punctum” that can arise from the innate characteristics of the medium.

The Archive Project(2011) was born from Back’s desire to mobilize the memories of individuals in order to reproduce a single story. Rather than addressing any specific issue, this series highlights the more neutral stance of the artist, and thus relies heavily on viewer participation. Instead of shooting his own photos, Back collected negatives of about 50,000 photos taken by anonymous people. He then developed about 2,700 of those photos, and arranged them to formulate a story. Minimizing the creative intervention of the artist, he enacts a process in which random images produce clues that elicit various memories and stories in each individual viewer. By surrendering control, he produces a fabricated virtual world wherein the viewer immerses herself in a deluge of images that trigger spontaneous interpretations and manipulations, not to mention contradictions and data errors. Back asked friends and acquaintances to help him select suitable images from the collected photos, arrange the selected photos to make a series of stories, and then determine the order and exact date of each image. Based on clues from the photos, the participants used their own inferences to compose a story, arrange the photos in the proper order, and add titles to the photos. Then, viewers at the exhibition look at the arrangement of photos, consider their titles, and try to guess the intended story, while also appreciating the photos in their own way. With Archive Project, Back Seungwoo was able to use photography to create a highly effective illusion, convincing viewers of their ability to discern the truth from a story.

At the 2012 Busan Biennale, Back presented panoramic photos of Busan, wherein he creatively reconstructed the complex, labyrinthine landscape of the city’s streets and buildings. Although there were evident differences between the photos and the actual city that unfolded before the viewers’ eyes, the landscape composed by the omniscient perspective was indeed Busan; all of the familiar landmarks were visible, scattered here and there among the complex but familiar tangle of streets. Although the image of Busan that we may have stamped in our minds might not be entirely accurate, it provides certain visual cues that are instantly identifiable. By simultaneously contemplating their perception, a visual image, and the real phenomenon, viewers experienced the alienation of information that can be generated from the conceptual judgment stipulated as “Busan,” the special region. More than a case of ordinary parablepsia, this sense of alienation is a common experience familiar to every individual. Poignantly resonating with viewers and eliciting a response based on their own private experiences, this work superbly demonstrates how the errors that arise within every system (which he had exposed in his earlier works) can also operate at the individual level. As such, the audience is encouraged to consider the possibility of close intervention between each individual viewer and the artist’s creative work.

I initially raised the question of Back’s strategy with regards to the limitations of the medium of photography, which emerge from the gaps between reality and the photo. But in the end, this question might not be so important to Back Seungwoo’s works, because of his astonishing ability to unveil the expansive potential of the medium. He certainly inspires us to anticipate the new possibilities that he might divulge in his future attempts and works.

Critic 2

Photography That Questions Photography Through Photography

Shin Boseul (Curator, Total Museum of Contemporary Art)

Back Seung Woo is a photographer, but there is something very different about his photographs. In fact, Back’s photography is not “shot,” per se, so much as it is “drawn” or “fabricated.” Thanks to developments in digital technology and computer editing, the notion of “fabricated” photography no longer raises any flags. But Back does not just digitally manipulate his photographs like everyone else. His photographic works are characterized by various striking features that make them indelible.

To discuss the uniqueness of Back’s photography, it helps to revisit the dictionary definition of “photography.” The word “photography,” which is credited as having been coined by Sir John F.W. Herschel in 1839, is defined as “the process of producing images by the action of radiant energy and especially light on a sensitive surface.” The word “photography” derives from the Greek words “φώς” (phos) meaning “light” and “γραφίς” (graphis) meaning a “pen, stylus, or paintbrush,” which in turn comes from “γραφή” (graphê) meaning “to draw.” Here, it becomes clear that the original conception of photography was to “draw with light.” To create photography, all one needs is light, an object or objects, and an apparatus to capture the light (i.e., a camera). However, recent developments in digital technology have fundamentally altered this conception, by allowing for the production of photography without objects, or without even a camera. In a world overflowing with fabricated and transformed photographs, what is photography? Back’s work begins from this question. He once said that taking photographs in this age of abundant digital images is meaningless, like “shooting a water-gun while underwater.” What possibilities are left to him as a photographer, or more so, as an artist? After all, having an advanced education in photography, he understands better than anyone the importance of proper photography for his art.

Back’s experimentation with photography that goes beyond merely shooting objects can be traced back to his Blow Up series (2005-2007). In 2000, he had the rare chance to visit North Korea. In preparing for his trip, he ambitiously packed a great quantity and variety of film, determined to capture an abundance of unique images that differed from the existing photography of North Korea. Upon arrival, however, he soon realized that he would not be able to shoot North Korea any differently from previous photographers, since he was constantly accompanied by a North Korean guide who strictly directed him as to what he could and could not photograph. Furthermore, his photographs were developed and printed by North Korean censors. Constricted by such circumstances, Back quickly lost interest in his North Korea photography project. When he returned to South Korea, he put all of his photos from the trip in a box and forgot about them. But then, about four or five years later, he stumbled upon an exhibition of photographs of North Korea taken by a French photographer. Wandering through the exhibition, he spotted a photograph of a North Korean girl holding flowers, who looked very familiar. In fact, Back started to think that he may have met and photographed the very same girl during his own trip to North Korea. Back at home, he dug through his photographs of North Korea, and then began to enlarge them. Through this process, he noticed things that he had not seen before, things that the North Korean censors could not control.

As his documentation of these unexpected moments and scenes was disclosed, he composed new stories from the photographs. The photos themselves often looked strangely cut or out-of-focus, since he only enlarged certain parts. Seeing these works, viewers accustomed to pristine, well-shot photographs might feel a bit of shock or embarrassment. At first, it is difficult to determine what we are supposed to look at, or what the artist’s story is. But the title of each work provides a starting point, from whence we can begin to make some connections. The title of the series—Blow Up—refers to the act of enlarging a photograph, but Back emphasizes another meaning of the term: an explosion. When something explodes, its physical attributes and circumstances are completely changed. Thus, an explosion is not only a form of destruction, but also of creation. This process is similar to taking one part of a photograph and enlarging it, such that it simultaneously loses its original context and gains new meaning. Whereas most documentary photographs of North Korea deliver some information about the country or convey the clear intentions of the artist, the photographs of the Blow Up series do not provide any proper information about North Korea. Instead, they bounce off the existing context, hinting at the possibility of different interpretations. Through this “explosive” process, Back’s photography loses its capacity for documentation and its denotative significance, but the images themselves acquire originality. The resulting works represent a challenging question and bold experiment aimed at the medium of photography. At the same time, they embody the doubt that increasingly characterizes our attitude towards photography. Although all of the photographs of Blow Up were taken in North Korea, they should not be featured in an exhibition about North Korea, or regarded in a political context. Indeed, emphasizing North Korea only serves to diminish the power of the works, and thus misses the point of Back’s photography. The defining characteristic of this series is not the fact that it was shot in North Korea, but the questions and doubts that it instills with regards to our attitudes about the essence of photography.

With Utopia (2008-2011), another series related to North Korea, Back more actively challenged our prevailing ideas about photography, albeit from a slightly different angle. In Japan, he visited a shop called Rainbow Trading, which sells a variety of goods related to North and South Korea. In this store, portraits of Kim Ilsung and Kim Jongil are hung alongside photos of South Korean celebrities (e.g., Bae Yongjoon and Ryu Shiwon), and albums of North Korean military songs are mingled with pop albums by South Korean singers such as Cho Yongpil. The state ideology has no jurisdiction over the shelves of Rainbow Trading, where every image simply represents a commodity to be consumed. Browsing this strange store, Back discovered photographs of buildings taken by the North Korean government. For Utopia, he mixed these photographs with those of buildings in South Korea, along with images of fully constructed buildings that exist nowhere. To create these “non-existent” buildings, he borrowed from the minimalist architecture of German Bauhaus, or the drawings of the Russian abstract painter Lyubov Popova. For Back, seeing something that, for all purposes, could exist, but yet does not exist, is a stereotypical sensation aided by the traces of existence that are inherent to the medium of photography. He called these buildings “utopia,” implying a certain kind of paradise. But the mere convergence of buildings from North and South Korea does not guarantee such a paradise. Of course, the etymological roots of “utopia” are οὐ (“not”) and τόπος (“place”), i.e., “no-place.” With this in mind, the questions posed by these fictional buildings suddenly do not seem so simple.

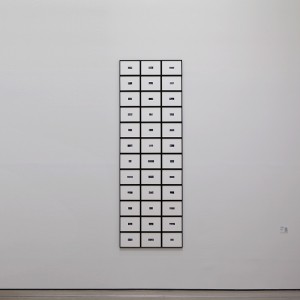

In particular, Utopia-#032 (2011) exemplifies Back’s doubts about the medium of photography, while demonstrating how the landscape of photographic production has been irrevocably altered by digital technology. Back divided a single image into thirteen parts, and then sent each of the thirteen parts to a different country for printing. He specifically requested that each print be made with the exact same settings and paper type. However, as might be expected, the final prints showed differences in color tone. This work has often been interpreted as delineating the subtle differences that are inherent to huge societies, but perhaps more interestingly, it reveals the fallacy that digital technology can yield identical works. Viewing the discrepancies between these thirteen photographic fragments, we are reminded that photography is not the same in any two places. Photography is a type of utopia, a “no-place” that cannot be realized in our world.

Back’s Re-Establishing Shot series (2012-2015) resembles his Utopia series in terms of attitude, although the individual photos look completely different. In Re-Establishing Shot, we see roads spreading in all directions and dense arrangements of buildings, seemingly representing one of the world’s major cities. But in fact, these photographs are assemblages of images of numerous different cities around the world. As such, this series depicts a city nowhere. Among the countless images of cities that we see every day, this series still manages to grab our attention, thanks to Back’s emphasis on urban structure. In the background materials for this exhibition, he stated that every city operates in the same basic fashion, regardless of its historical or social background. Thus, the images of Re-Establishing Shot are not so much computer-generated photography of a non-existent city, but rather photographic portraits of abstract concepts supporting the contemporary society of the “city.” Even though each road and building corresponds to an actual object, the result is still meaningless. Dozens of broken fragments of reality are compiled into a single new image world. Whether or not they refer to a concrete object, the resulting images operate by formulating a new meaning structure within this new virtual image world.

Back continually questions the essence of photography, and then tosses those questions at the audience by blatantly distorting the elements of photography that we believe to be essential. All of the photos of the Blow Up series were taken by Back himself, and he personally discovered the photos of the Utopia series, meaning that their source is relatively clear. On the other hand, his work Memento (2011) consists entirely of photos from various archives, the sources of which are either unidentified or no longer relevant. Thus, Back further distances himself from the medium of photography. After creating a certain situation, he quietly fades into the background, becoming an observer who wishes to examine how photography produces meaning, how it is related to memory and documentation, and how viewers consume and interpret images.

Memento derives from a collection of 50,000 photographic slides, representing someone’s most personal memories, which Back purchased at a flea market in the United States in 2011. After narrowing this massive collection down to about 2700 slides, he invited eight of his friends to each choose eight photographs. The participants arranged their eight photographs in their own way, and came up with a story and title for their selected images. Four years later, he sent these sixty-four photographs to eight people with different professions (e.g., medical doctor, lawyer, art critic, curator, actor, engineer, etc.). As before, he requested the new participants to select eight photographs and to form their own narratives, and then exhibited the results.

As implied by the title, Memento is primarily concerned with remembrance. Photography is often regarded as a supplementary device for our memory. But even though a moment may be captured in vivid detail by a photograph, the feelings and sensations of that moment inevitably change over time. Just as a photograph deviates from both the depicted object and the depicting subject, the meaning of a memory is distinct from that of the original experience. Moreover, the transference of a photograph to an unrelated third party allows new stories, guesses, and visions to emerge.

All of these works force us to question the role of the artist. Is the artist simply an observer who establishes a set of circumstances and then watches the aftermath? For Memento, Back purchased and distributed the slides, but the exhibited works represented the choices and stories of his participants. Naturally, the stories imagined by the participants have no relation to the original meaning and context of the photos. But if viewers feel any doubt or discomfort from seeing new narratives attached to a photograph, or from wondering about the validity of those narratives, those feelings can only be attributed to the artist who established the conditions of the project. If we ultimately feel that these works challenge our beliefs that photographs are records of facts, or that each photographed object has a single innate context, then Back Seung Woo is performing the role of artist more actively than ever before.

Although the works of Back Seung Woo take very different forms, they all address his doubts about the essence of photography. This is true whether he is utilizing his own photographs or existing archives, whether he is manipulating photographs through Photoshop or other means, or whether he is enabling the intervention of a third party. But in this era of digital imagery, when the idea that photography is a record of fact has been all but abandoned, why should anyone bother to address these issues with such diligence and passion? Being fully aware of the endless possibilities for manipulating photography, most people already distrust photographic images, even without seeing Back’s laborious works. All the same, the role of an artist is always open to interpretation, and these works can raise viewers’ awareness of their own unconscious ideas about this issue. In this regard, they are eminently worthy of our interest and attention.

Back’s exhibition Blank Medium for the Korea Artist Prize 2016 represents an extension of his previous work, incorporating all of his questions about our perceptions of images. The term “blank medium” refers to the base data of a memory storage device, i.e., the small portion of computer or digital memory that is unavailable to users. For example, a 64-GB memory card actually contains about 60 GB of available memory, with the remaining 4 GB comprising unalterable program data that allows the device to operate; in this case, the memory card has 60 GB of blank medium. For Back, anyone working in photography is operating in the realm of this blank, unwritten space. Naturally, this process of filling in the blank space is based on perpetual doubts about the fundamental aspects of the medium. Artists who experiment with our stereotypes of photography or the changing landscape of photography are filling in the blank of the medium of photography, and in the process, producing an entirely new medium. The four new works shown in this exhibition—Betweenless, Framing from Within, Wholeness, and Colorless—can be understood as compressed representations of Back’s thoughts on photographs as representation of fact, photographic archives, and his concept of “picture,”1 all within the context of photography as blank medium.

Interestingly, although Betweenless and Framing from Within proceed in a similar fashion, they present conflicting results. Like the Blow Up series, Betweenless consists of enlargements; in this case, Back enlarged images of people from various 35mm slides that he has collected. In line with his previous works, Back does not enlarge the primary subjects of the existing photos, but rather peripheral figures who were chosen based on the artist’s own rules. From the moment that these figures are cut away from the original photographs, their contexts are deleted. Through the process of enlargement, all the information about their identity is removed, leaving only rough, blurry outlines and colors. Like a detective trying to find a criminal through a montage of clues, the viewers must struggle to identify the people using only their own education and experience.

If the essential functions of photography are documentation and verification, then the works of this series may be seen as “failed” photography, which thus damage and undermine the status of photography. But they must still be understood as a new archive of images created through the intervention of the artist. As Back himself said, he constructed his own “picture” archive by damaging the existing archives.

Also like the Blow Up series, Framing from Within emphasizes different ways of seeing photography. When viewers look at a photograph, they generally see the foreground figure (or figures), the background setting, or the overall composition. But Back takes a different approach by focusing on peripheral figures who accidentally appear in the background of his photographs. From the beginning, he does not know who these people are, and he further removes them from the original contexts by reframing them. In this way, he created a new archive of thirty-six “accidental” images of people who did not intend to be photographed and whom the artist did not intend to photograph.

Wholeness continues Back’s interest in “picturized” photography based on archives. The work consists of five different prints of a single image taken from a public archive in the United States; notably, each of the five prints is a different size. Although photographic archives are generally associated with memory and documentation, this particular image has lost that function, since it does not convey any practical information. Unable to perform its expected role as an archival photograph, its is transformed into a pure image. In other words, a photograph becomes a “picture.”

The fourth new work, Colorless, is an installation based on commercial billboards with rotating panels, which allow them to show three different advertisements. Here, the three sets of panels show (respectively) a grayscale chart, the color tone “18 Gray” (i.e., the general standard for median gray, referring to its 18% reflectance of light), and a line of text: “EVERTHING IS PURGED.” Both the grayscale chart, showing brightness levels from white to black, and the median gray color, the benchmark for measuring exposure, represent “average” values within the medium of photography, and thus imply efforts to standardize the medium. Nonetheless, the panel of text clearly represents the artist’s refutation of such standards, and his belief in the need for a shift from “photography” to “picture.”

Discussing the perception of Back’s work as “pictures,” rather than as “photography,” Moon Youngmin explains:

“The objects in Back Seung Woo’s photography are not so much the actual objects themselves as things that have been ‘picture-ized.’ They are something we instantly recognize. His photographic images capture what has originally been there. In so doing, they present images that are already familiar pictures, rather than fulfilling photography’s fundamental essence as an index.” (Moon Youngmin, “Out of Pictures, Out of Archive”)

This concept of the term “picture” evinces the ways in which Back’s photography differs from existing photographic images, as well as the different mode of perception that viewers must utilize in order to understand his works. In Framing from Within, Back Seung Woo intentionally subverted various modes of perception that have generally been associated with photography. For example, he installed small photos, which can only be properly examined up close, at a great height, distant from the viewers’ eyes. People who are familiar with the ways of appreciating photography might squint and struggle to perceive these photos, in an effort to understand their source and the artist’s intended meaning. But such efforts are inevitably futile, since the tiny figures look like ants, indiscernible from another. By disrupting the comfortable distance between the work and the viewers, Back causes the eye of the viewer to slip from the photos, as if each one were an individual pixel. As such, the viewers cannot hear the artist’s voice in the images, an effect that he has also achieved through different methods in Betweenless, Utopia, and Re-Establishing Shot. Although we can see his photographs, we cannot properly read them. Photographs can only have meaning as reconstructed images. But by removing all information and context, Back prevents us from reconstructing the images, and thus impedes our usual mode of forming meaning from photography. In so doing, he causes us to notice and appreciate the surface characteristics of the photograph, such as the color tones and composition. Here arises the autonomy and independence of picturized photography.

Paradoxically, viewers who wish to grasp the Back’s intention and the meaning of his works should perhaps stay away from his photographs, for the meaning does not lie in the photographs themselves as in his attitude and method of production. Many of his images look amateurish or incomplete, making them impossible to interpret. They are certainly not restricted by academic regulations about what photography should be, which is likely why viewers often complain about the difficulty and inscrutability of his works.

These complaints arise from the fact that Back’s images cannot be reached by our usual methods for appreciating photography. From Blow Up to Colorless, he adeptly fluctuates between photography and the various conditions surrounding photography. While the physical results may in fact be photography, they can only be grasped by considering the surrounding conditions. In a world saturated with photography, Back’s voice stands out and never falters, even though he is simply “shooting a water-gun while underwater.” All of his works can eventually be reduced to a single question: what meaning can photography have in a world where photos can be taken by anyone, anytime, and anywhere? In particular, what does it mean to an artist? For Back, the only way to question photography is through photography.

Back Seung Woo considers photography as something to be painted or drawn, rather than shot, as demonstrated by his process of making “picturized” photographs. Given that so many of his works involve the archival function of images (e.g., Blow Up, Utopia, Memento, Wholeness), it might seem that his overriding theme is “archive.” But in fact, that is not the primary theme of any of these works. He simply uses photos from archives in the same way that a painter uses paints. As such, “archive” is closer to a material for him, rather than a theme. Again, in discussing his works, the emphasis should be placed on his method of cropping, enlarging, and resizing photographs that he has selected, as well as on the idea of “painted” photography. Archives are a crucial material that allow Back to “paint” picturized photography, as well as the foundation for interpreting his photography at various levels.

Photography is clearly a “blank medium” for Back. Rather than concerning himself with the characteristics usually associated with high-quality photography (e.g., sharp focus or striking composition), he incessantly seeks to raise doubts about the elements of photography that are usually taken for granted. He simply fills in the void of the blank medium in diverse ways. The resulting “painted photography” suggests new ways of seeing photography, and indeed an entirely new form of perception.