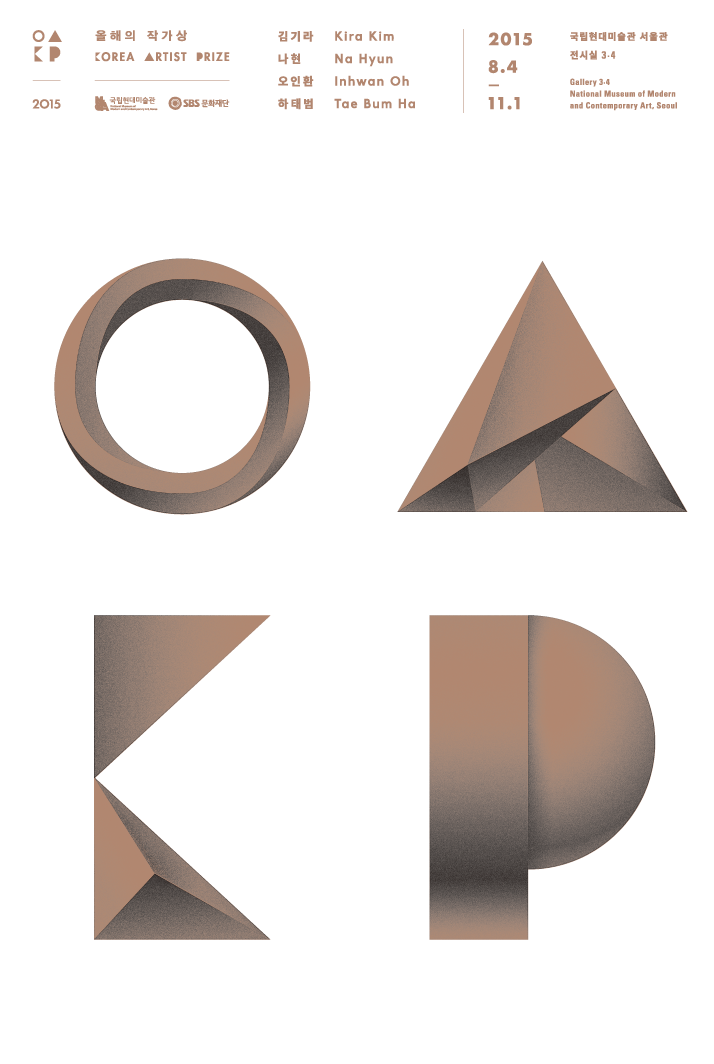

2015

《2015 Korea Artist Prize》

Dong Eun Ma

(Associate Curator, National Museum of Contemporary Art, Korea)

Greeting its fourth year, ‘Korea Artist Prize’ is a system co-organized by the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea (MMCA, Korea) and the SBS Foundation adhering to the mission of promoting artists with great possibilities, vision and new alternative to Korean contemporary art. From the year 2015, ‘Korea Artist Prize’ will be held at the Seoul branch of MMCA, Korea.

For the fair operation of Korea Artist Prize 2015, a steering committee (5 members) was established and the steering committee appointed separate recommendation (10 members) and judging committee (5 members). Each recommendation committee member endorsed an artist/a group, and through strict evaluation process by the judging committee composed of international art professionals, four artists were selected to participate in Korea Artist Prize 2015. The shortlist for this year includes Kira Kim (b.1974), Na Hyun (b.1970), Inhwan Oh (b.1965) and Tae Bum Ha (b.1974) and these four artists will present their latest projects in this exhibition. Henceforth, one artist will be awarded as the ‘2015 Artist of the Year’ through the final evaluation process during the exhibition period.

For this exhibition, Kira Kim’s tells the story of ordinary lives surviving the insecure today and Na Hyun’s displays the archaeological study of historical experience and city development of Seoul and Berlin in a solid way. Inhwan Oh extends the spatial significance of blind spot to the context of society and culture whereas Tae Bum Ha reinterprets the attitude of mass media in delivering the scenes of accidents and incidents.

Kira Kim : Floating Village

Kira Kim (b.1974-) is an artist who actively expresses the social responsibility of art and artists through performance, installation and video. The method of Kim’s visual language is grounded upon the gesture of editing the various collected symbols through his own peculiar humor and metaphorical syntax, thereby discovering the relationship among the modern society, individual, and a venue of public dialogue.

Kim is interested in the socio-cultural position of an individual in the current capitalist society as well as the desire of a person and group in opposition to this. Kim continuously collaborates with professionals from different genres, forming a multilayer community. He explores the pivotal point where this process and results are combined together with visual art and eventually the labor of thought becomes a work.

‘Floating Village’ generally refers to the house built on water. Kira Kim borrowed this compound word as the socio-cultural and conceptual term to show an aspect of our society. The concept of ‘Floating Village’ holds the story and experience of the minimum scale of village as ‘floating’ signifies the current of information through personalized media and ‘village’ is derived from the Bible verse where every individual is ascribed as ‘home (temple)’.

Under the proposition of ‘common good’, Kim intends to unravel the issues of collision, conflict and opposition within the reality, history, ideology, politics, generation, region, and labor union of the Republic of Korea in aesthetical perspectives. He collaborated with numerous professionals from different genres including film director, psychiatrist, voice actor, dancer, poet, on-site artist, actor, singer and etc. The procedure and results of the collaboration are presented in his works, Weight of Ideology–Darkness at Noon (2014), Red Wheel (2015), and Floating Village (2015) as video installations.

The works of Kira Kim could be divided into three large parts: private ownership, common sharing, and public enjoyment. The ‘private ownership’ shows how the private realm of personal experience and the wound of the history turn into the discourse of memory and perception. ‘Common sharing’ reveals how the discourse of the private domain converts into the illusion of the unrealistic phenomenon of art, further penetrating into a venue of public and common discussion. Lastly, ‘public enjoyment’ suggests the premise that an unrealistic place, even more realistic than an existent place expands into the public space, thereby reproducing another venue of discourse.

Na Hyun : The Babel Tower Project-Nanjido

Na Hyun (b.1970-) works with projects that connect the past and the present based on data and documentation of historical events and records. He first collects and analyzes an assembly of archival data from history, anthropology and cultural anthropology. Then he constructs his own subjective and creative archive through actual historical site visit and research. Na Hyun’s central interest lies in the historical events, which are inevitably related to humanity and ethnicity as he translates these into his own aspect and induces the viewers to expand their imagination apart from the commonly learned history.

“When all men were of one language, some of them built a high tower, as if they would thereby ascend up to heaven, but the gods sent storms of wind and overthrew the tower, and gave everyone his peculiar language; and for this reason it was that the city was called Babylon.”

(Antiquities of the Jews 1.4.3)

Na Hyun has been suspecting the Devil’s Mountain (Teufelsberg) of Berlin and Nanjido of Seoul as relics of the Babel Tower and thus presents his research project, The Babel Tower Project-Nanjido to explore the socio-cultural significance. The Devil’s Mountain of Berlin was built at the end of World War II as the ruins of the war were piled up into a 120 meters artificial mountain in the Western Berlin area for the reconstruction of a demolished city. On the other hand, Nanjido located in the west end of Seoul was a site of landfill, unparalleled in the world history with piles of 95 meters high industrial wastes produced from the rapid industrialization from 1978 to 1993, often called the ‘Miracle of the Han River’.

In this exhibition, Na Hyun excavates the stratum of time and memories of the modern and contemporary era of the Devil’s Mountain and Nanjido. He installs a wooden well as equipment connecting the past and present, thereby exposing the innate attributes of agitation and violence underneath. He especially pays attention to the meaning of ‘minjok’ (race or ethnicity). As a metaphorical gesture of displaying the record of the Babel Tower and the Mischehe discrimination legislation in German congress about a century ago and the rapid diffusion of multi-racial society in the 21st century Republic of Korea as a country once confident of being a single-race nation, Na Hyun transplanted various naturalized plants collected from Nanjido unto the Babel Tower in the exhibition space. In addition, he also placed interviews of the foreigners who live in Korea and people of Korean race who live overseas to attest that Nanjido is one kind of a Babel Tower through the origin and proliferation of heterogeneous race and language. In account of this, Na hyun insists that Babel Tower is not just a myth or a fantasy of the past but a phase of reality in progress everywhere around the world.

Inhwan Oh : Finding Blind Spot

Inhwan Oh (b.1965-) works on participatory and site-specific projects utilizing the context of particular space and time. Oh initiates from the issues of identity and further expands to the fundamental question of correlation between the societal regulations and the arts, attempting to deliver cultural criticism in conceptual and experimental methods. Based on his personal experiences, Oh translates or dismantles the cultural code formed in the pertinent context of relationship between individual identity and group within the patriarchal society. He also proceeds on with concrete and practical works relevant to the daily experiences, merging the keywords of contemporary art including, difference, variety, communication and more.

Reciprocal Viewing System (2015) utilizes the surveillance camera installed in the exhibition space, providing spatial experience of the blind spots to the audience. Oh discovers the blind spots of the installed surveillance cameras in two separate spaces and visualizes these blind spots with colored tapes. The surveillance camera transmits the interior of the exhibition space to the monitor in the other space though this cannot be seen through the monitor installed in the blind spot areas. The audience could actually encounter the visualized installation by an in-person visit to the exhibition space and find the difference between viewing through the monitor screen and physical on-site viewing.

My Blind Spot-The Interview (2014-2015) is a collection of personal cases of finding blind spots. Arranged with the interviews on several men discharged from military services, each man introduce their personal experiences of finding private spaces within the army and thus the artist sheds light on the essence of finding blind spots in intimate experiences.

Guidelines for Finding One’s Own Personal Space (2014-2015) is an assortment of guidelines for finding blind spots in the barrack, told by the participants in My Blind Spot – The Interview. The guidelines suggested by different individuals are rearranged in Korean alphabetical order and presented in the exhibition space in paper labels or projections. This is a method of sharing each discrete experience and also a collective voice of the members in the society sharing particular experiences together.

My Blind Spot – Docent (2015) is a work that reconnects with Reciprocal Viewing System through performance. This performance is organized in one to one tour guide, limited to the desiring applicants. As performers, the docents will perform in guiding the applicant to the two separated spaces.

I am not an artist/ I am an artist (2015) is a compilation of interviews on people who once received education as art professionals or began their career as artists but gave up their activity or career in the art field. Becoming an artist today means enrolling into the system of academies, exhibitions, residencies and etc. and at the same time, it also means artists interfering into the system of art. Inhwan Oh intends to reflect upon the definition and role of artists through the correlation between individual artists and the system in I am not an artist/ I am an artist.

Finding Blind Spot (2015) begins from accumulating the discharged soldiers’ methods of finding blind spots for personal use during their service and making instructions with all of their directions. Inhwan Oh follows these directional instructions as a moving performance and this process is filmed by the artist holding a camera upwards to the sky. This video, filmed in multiple spaces, is compiled and recomposed through editing. When traveling along the same directions in different places, discordance is bound to occur and this demands an interpretive role of the performer. Hence, each performance space could be different contexts for interpreting the directional instructions. Inhwan Oh’s performance of finding blind spot is a repetitive process of following the congruent instructions as well as unveiling the contrast in the process of comprehending union of variant place, time and gesture.

Tae Bum Ha : Gaze on the Incident

Tae Bum Ha (b.1974-) collects images of several incidents and reported news photographs uploaded on the internet everyday as main data for his works. These images are mostly captures of the destroyed buildings, wreckage and ruins of conflict areas or natural disasters. The artist rebuilds these images into white miniatures and completes them into photographs. Through the blank space created by intentional deletion of the background, he gradually maximizes his indifferent perspectives. Yeonpyeongdo (2011), Japan Tsunami (2012) and Tondo in Philippines (2014) were produced in the respective context.

On the other hand, only the faces of children are accentuated in Line of Sight (2015) series. Tae Bum Ha encountered images of displaced boys and girls from the advertisements of different non-profit relief organizations. According to the artist, if news were to ‘provide’ gruesome scenes of the accidents, then these non-profit relief organizations ‘provide’ appearances of the people in such pain whereas also eliciting ‘opportunity’ to participate in something. These relief organizations exclaim that we could save someone’s lives with just 20,000 won per month. How desirable is this? The artist also donates small portion every month. However, the helping hands have been continuing on for many years and our lives seem to be in better shape, though these people still suffer in hunger and death. The various media and gigantic billboard displays more photographs of children in sorrow and the artist feels dreary of the escalating number of such advertisements day by day. Nonetheless, who exactly are the faces appeared in these advertisements? Yet in an instant, the artist thinks it is not important to know who they are. They are just symbols of children from a certain starving country, sacrificed in the tornado of war.

Ha believes that they are not portraits of individuals but medium of symbolic icon that stimulate our sadness and sympathy.

“Aren’t these donations for our own indulgence rather than for truly aiding them?”

The artist quietly declares that this is the current story of you and I.