2014

《2014 Korea Artist Prize》

Park Soojin

(Associate Curator, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea)

Now in its third year, the Korea Artist Prize (2012- ) adheres to its mission of promoting vibrant art scene within Korean Contemporary Art with the field centered, substantial support program for Korean artists, selected through fair and open process. The National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art conducts this award in collaboration with the SBS Foundation. The award targets artists who have consistently demonstrated innovative and experimental spirit with capacity to stimulate novel discourses in the international art sphere.

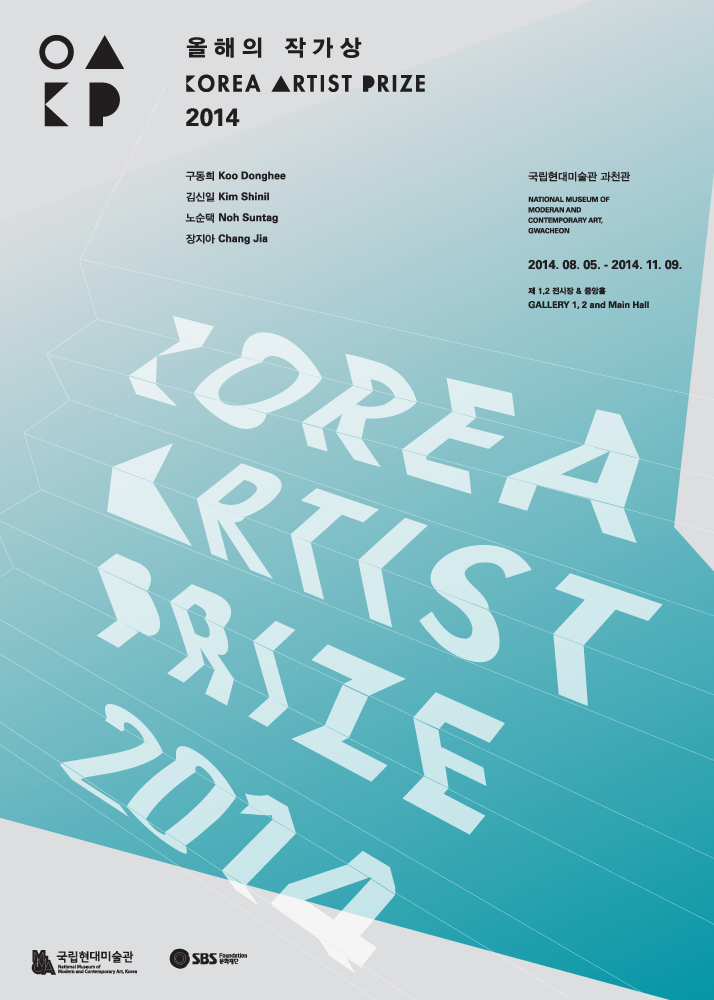

For 2014, a new steering committee (2014-2015) took over the guidance of Korea Artist Prize. For the fair and open operation of the award, the committee decided that the recommenders and judges would be chosen separately. In awarding the prize, the steering committee first commissioned ten esteemed art professional figures to recommend one artist each. Then, after evaluation by a panel of five Korean and international judges, four finalists were chosen to be featured in the exhibition for the 2014 Korea Artist Prize. This year’s finalists are Koo Donghee, Kim Shinil, Noh Suntag, and Chang Jia. For this exhibition, these four artists were given wide spaces in which to present large-scale project of their choice. The final exhibition allows viewers to experience the brilliant minds and stunning achievements of Korea’s finest contemporary artists. The aforementioned panel of judges will select one artist to receive the 2014 Korea Artist Prize, and the recipient will be announced during the exhibition period.

Koo Donghee : Way of Replay

Koo Donghee (b. 1974) creates video works and installations that reveal how the fabric of daily life can be torn by the occurrence and intervention of accidental situations. For her works, she collects coverage of current events from various media, and then develops the visual elements of the piece by playfully re-assembling this material like a puzzle. Rather than taking a critical stance towards a certain issue, she accepts the limitations of the situation and applies her artistic imagination to shape her works in accordance with those limitations. She particularly enjoys seeing how her original intent gradually changes based on the logistics of presenting the work. In her videos, she often arbitrarily edits the material to produce a new narrative. Describing her process, Koo said, “Whenever I start a new project based on one of my ideas, I get very excited trying to envision what it will be like. But by the time it’s finished, I’m always embarrassed by the final product. The way I work is quite spontaneous. I always have a plan when I start out, but then my hands just move around as if they had minds of their own, and the result is usually something completely different from what I originally thought of. Whenever I finish a work, and I try to think about what I’ve done, my mind is blank, and I start to doubt whether I’ve done anything right. There’s always this repetitive pattern where I go up somewhere only to bounce back down to where I was in the first place.”1

Koo chose video as the medium for conveying her narratives, but her unscripted videos do not have any clear storylines, since no semantic elements emerge from the actions of the characters. Her characters simply invent themselves based on the artist’s description of the role as there is no script. The events leading up to and proceeding from an incident are left ambiguous, eliciting a sense of tension heightened by the unfamiliar characters and repetitive composition. The narrative itself is never discussed and any elements that may be explanatory are removed. Regarding Koo’s videos, the Japanese curator Azumaya Takashi said, “the absurdity in her works is based on the senses she actually felt in her life. She attempts to share that absurdity with the viewers through the temporal axis of the video, which differentiates it from daily spaces, as well as through the actions of people who are confined within the axis.”2 Koo desires to remain constantly aware of the absurdity that marks our irrational world, and she expresses this desire as the chaos of being jumbled together between the world and people.

Koo’s installation for this exhibition is Way of Replay (2014), which is based on her own memories of the nearby Seoul Grand Park, as well as her impressions of some recent accidents and incidents on the news. When asked to plan an installation for the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Gwacheon, Koo immediately thought of the roller coasters from Seoul Land amusement park. Thus, she created and installed a large twisting track—reminiscent of a Möbius strip—as a way of encouraging the audience participation within the rectangular symmetrical space. The structure is 75 meters in length, with a rotation of 270 degrees, and also features 36 modules. A Möbius strip is a looped surface with only one side and one edge. With a single twist, the upper and lower surfaces are seamlessly transposed, allowing the surface to realize infinity. In the extremely twisted point of the installation, a video shows the infinitely repeating shot from the rollercoaster rider’s perspective. The work seems to suggest an organic relationship between people and the world, in which both sides develop through an incessant exchange of actions and reactions. Both sides begin from an internal perspective, which perpetually and ineluctably becomes the external. Entering the track and following the changes in the track’s structure, the audience finds it almost impossible to simultaneously maintain a comprehensive view of the structure and awareness of their own location within the structure. As they realize the separation between their perception as the experiencing subject and the illusion of the viewing subject, the objects surrounding the structure attempt to talk to them. These objects can imply the position of viewers, or visualize their situation.

In describing her experience of making this installation, Koo stated, “Sometimes one certain image leads to many other images. That’s what it was like for me. It kept getting larger and stronger, until I thought that perhaps I should start a new video work.”3 Koo Donghee exemplifies our perception of an artist as a person who is only able to endure her own experiences and emotions from daily lives. In her works, she implicitly materializes visual elements in a playful manner, thus opening multiple possibilities of interpretations.

Kim Shinil : Ready-known

Kim Shinil (b. 1971) produces visual creations that seek to deconstruct the boundaries of our ordinary concepts and views through the act of “seeing.” The renowned media analyst Marshall McLuhan provided a new critical perspective for thinking about media in his seminal 1967 book, The Medium is the Massage (the actual title of the book, based on his popular saying ‘The medium is the message’). McLuhan argued that technology itself unconsciously influenced its users by transforming and inhabiting their real life experiences.4 In agreement with McLuhan’s argument, Kim perceives that the people of contemporary society have been made passive by the overwhelming inundation of information and the non-stop categorization of the world associated with digital technology. Through his works, he seeks to expose and subvert our inherent—i.e. ‘ready-known’—ideas and beliefs.

Kim’s early works are ‘pressed-line drawings’, where he used a sharp tool to make delicate folds in plain white paper, using the folds as lines for rendering simple figures. By restricting the use of both form and color, the embossed drawings fluctuate between visibility and invisibility, depending on the direction of light. He also made videos by animating these embossed drawings, including Invisible Masterpiece (2004), which shows people staring at the empty walls of a museum. By showing the movements of people in a museum devoid of artworks, Kim questions the act of seeing, and particularly the notion that seeing is the path to truth. In TV Enlightenment (2006), Kim removed the texts and images from a TV commercial, leaving only the projected light from the television. Thus, rather than pacifying viewers with a unilateral delivery of information, he activates their senses and imagination with a barrage of light.

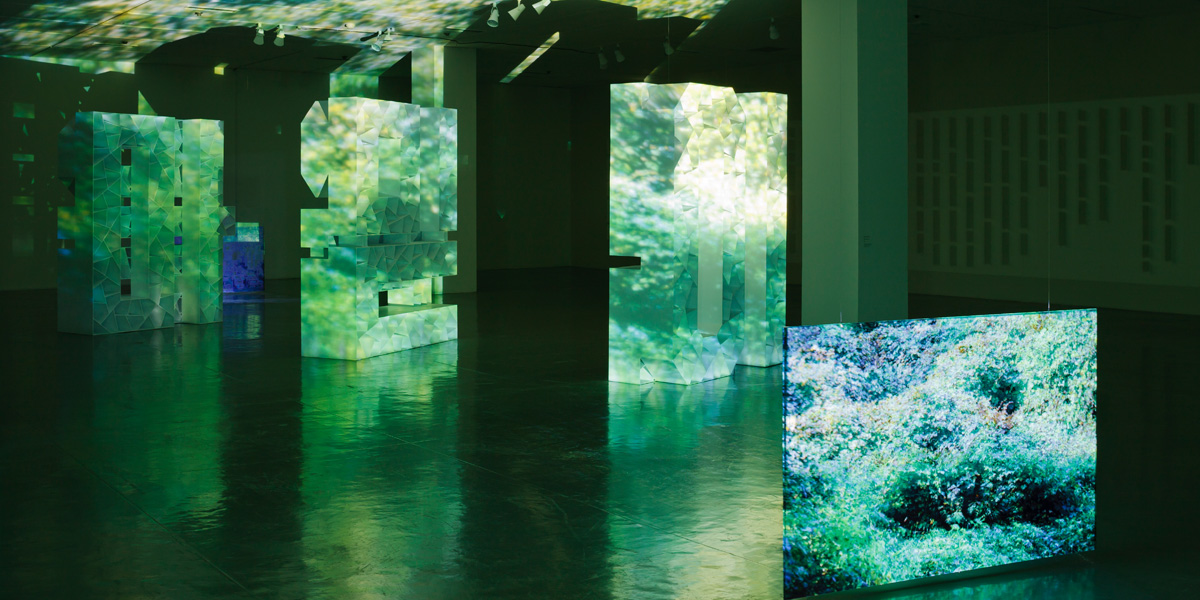

For this exhibition, Kim combines his letter sculptures with a video work to render the gallery space as a single structure. Sensors are installed to automatically adjust the sound and lighting according to people’s movements in the space. When the gallery darkens, auditory elements are emphasized to stimulate people’s perception through hearing; when the lights brighten up, visual elements are highlighted to engage their mental reasoning. Kim’s letter sculptures consist of abstract blocks formed by conglomeration of letters. These large blocks extend up from the floor to 2.4 meters high. Through these sculptures, Kim impedes the semantic function of words and letters and reconstitutes them as pure visual elements. Once the letters cease to exist as mere vessels for human thoughts, their overlooked sensuous aspects come to the forefront. As such, viewers find themselves in a place outside of meaning. In front of a mirror, some small letter structures are perched atop a thin pole, and are made to shake by low-pitched reverberating sounds. In the center of the exhibition space, Kim has erected three columns composed of three Korean words, each with two syllables, translated as ‘mind’, ‘belief’, and ‘ism (ideology)’. Light is projected onto and through these structures, so that their edged surfaces block and reflect the light like the folds of the embossed drawings. Walking through the room, people’s rationality is shaken (like the trembling letters), and their minds and emotions are shaken (like the rumbling sound and the mirror). Furthermore, by combining the sound of a heartbeat (the most basic sound of the body) and light (the source of life), Kim allows intuition to take precedence over the rational discretion. His attempts to intuitively grasp our true nature are perhaps best exemplified in his video, Into 42,000 Seconds of Conversation (2014). The title refers to the approximate number of seconds in 12 hours, the average amount of time that our reason is on alert during any given day. For this work, Kim took photos of the landscapes we encounter in our daily lives—both natural and artificial—and enlarged them until they became pixilated and unrecognizable. Two videos then intersect with one another, allowing us to approach truths that lie beyond the reach of human vision and reason.

Visitors must walk through a long corridor to reach the exhibition space, which is entirely white, the color of moderation and acceptance. It is almost as if they are being led into meditation or into a de-materialized world that is completely filled with emptiness. Perhaps it is the passage to the spiritual world that lies forever beyond the surface. Thus, through the act of ‘seeing’, Kim deconstructs our ‘ready-known’ ideas, using the basic units of light and sound to enact our intuition and guide us towards the true source of life. In his works, integrating drawing, sculpture, and video, Kim Shinil uses a simplified and reserved visual language to experiment with our sense of sight, and thus enhance our inner vision and awareness.

Noh Suntag : Sneaky Snakes in Scenes of Incompetence

Noh Suntag (b. 1971) produces photographs that detail real-life situations directly related to the division of Korea. He shows how deeply the division has permeated into the daily lives of the Korean people and has thus distorted the entire society. Since the division, little has changed with regards to the political and military situations of North and South Koreas, or with the attitudes of the people. These days, the division is rarely a topic of discussion; it is unconsciously accepted like an established fact of life. Yet Noh doggedly continues to expose and examine the myriad ways in which the ideology of the division manifests itself within daily life in Korea.

After beginning his career as a documentary photojournalist, Noh has published numerous books of photography: Smells like the Division of Korean peninsula (2005); The strAnge ball (2006), focusing on the “Radome” (radar + dome) of the U.S. military in Daechu-ri, Pyeongtaek; Red House (2007), documenting the differing aspects of North and South Korean society; State of Emergency (2008), winner of the 2008 “German Photo Book Award”; ReallyGood, Murder (2010), examining the exposure of war weapons; Hear the Song of Gureumbi (2011), featuring interviews with residents who opposed the construction of the U.S. naval base in Jeju Province; The Forgetting Machine (2012), looking back at the Gwangju Democratization Movement; and In Search of the Lost Thermos Bottle (2013), dealing with the North Korean shelling of Yeonpyeong. The overall theme penetrating all of these works is how the division functions through malfunctioning. As Noh himself noted, the division “does not necessarily occupy a specific time or space. The division freely floats and permeates….Thus, it instigates both memory and forgetting, and a sense of both security and anxiety.”5

After Smells like the Division of Korean peninsula, Noh continued to contemplate the inherent narrative of documentary photography, which ostensibly attempts to highlight facts and directly expose the truth. The photographs in The strAnge ball initially look like documentary photographs, but they clearly convey the aesthetic sense of the artist, not through a straightforward message, but through compressed and symbolic images. Likewise, in ReallyGood, Murder, the image of a bomber against the blue sky resembles a lovely painting, but Noh shows it to us upside down, as if it were falling, thus amplifying the precarious sense that comes from seeing such a murderous machine. To help expand the viewers’ imagination beyond the frame, Noh frequently juxtaposes his photos with various phrases, often consisting of counterintuitive expressions or wordplay of the Korean language: ‘insane sincerity’, function and malfunction’ and ‘good, murder’. These phrases seem to be Noh’s intentional twists, which he uses to illustrate the cross-section of Korean society, as well as the widening gap between the perception of the system and that of the people. This exhibition questions the daily operation of Korean society, and particularly the increasing role of cameras within that operation. Today, the conditions of photography have greatly changed, with almost everyone having a camera with them at all times. As such, the act of taking pictures has become an integral part of people’s daily lives. Amidst these current circumstances, Noh captures people aggressively pointing their cameras to commemorate or document specific socio-political events, including sites of protest where conflicting interests are clashing. Through such photographs, he shows how cameras can be used like a weapon to attack opponents, but also exposes the limitations of photography. In the exhibition title, “sneaky snakes” refers to the somewhat insidious yet explosive attributes of photography, which has quietly revolutionized media within its relatively short history. The “scenes of incompetence” are unfortunate incidents and events that initially seem to be evidence of cruelty, but are more likely the result of mere incompetence, making them immune to moral action or outrage. While photography purports to convey the objective truth, it can subtly and shrewdly distort facts by presenting only a framed and superficial landscape devoid of context. For instance, recent coverage of social disasters in Korea has resulted in various accusations of the media’s subjective views. This exhibition reflects Noh’s self-examination about the actual medium of photography itself, i.e., how we should view photography.

By approaching Korea’s social problems as universal human issues, rather than as ideological conflicts, and by visualizing scenes with his own unique aesthetic sense, Noh successfully elicits the empathy of the viewers. Finally, the works in this exhibition reveal Noh as an artist who is persistently concerned with his own medium, particularly at a time in which that medium is changing so rapidly. Through these works, he encourages and enables us to re-examine how photography is circulated and provided in our society today.

Chang Jia : Taboos Stimulate Hidden Desire

Through various media (e.g., performance, video, installation, and photography), Chang Jia (b. 1973) utilizes the human body to address social taboos. She deals with the body as both a sensory system and a person’s innermost essence, rather than as a cultural product that reflects the social view. Her work can be associated with feminist art, in that she reveals women as desiring subjects, rather than voyeuristic objects. However, by using her artistic imagination to expose taboos relevant to all human bodies, she transcends the limits of classification and explores the broader boundaries of art. Chang has said that her works are “designed to inspire contemplation on personal privacy rather than public communication. Thus, they are expressed as private desires that are either forbidden by society or irrelevant to the prevalent social signs.”6 She believes that, before we can begin to express our social views or to change the world, we must first confront the intrinsic feelings that exist within each one of us.

Since 2004, one of Chang’s primary themes has been the fluids and secretions of the body, including urine, saliva, and blood. The result has been a series of works on topics that generally produce feelings of discomfort and even revulsion among people, not only in artistic terms, but from a larger social perspective: photos of a woman urinating while standing up, plants grown with urine, a collection of saliva, and bricks made from cow’s blood. When these works are viewed in a museum or gallery, Chang’s artistic imagination expands to encompass the experiences of the audience, while simultaneously eliciting their shame and humiliation. The resultant sensation is nothing less than abjection, the same nauseating combination of abhorrence and vulnerability that often comes from seeing graphic images of dismemberment or bodily discharges (e.g., semen, hair, vomit, excrement).7 These are anti-aesthetic works that seek to reconfirm social agreements by challenging social taboos. One of the works involving urine was P-Tree (2007), presented in the main hall at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, which included several fascinating drawings that demonstrate how Chang altered her original conceptions to accommodate the actual space of the exhibition.

All of Chang’s works exist at the point of intersection between various extremes—pain and pleasure, violence and beauty. In Beautiful Instruments II (2012), she reinterprets surgical instruments as implements of torture, demonstrating how we overlook their surprisingly aesthetic features due to their practical function. Sitting Young Girl (2009) and I Confess My Sins (2011) unveil the violence hidden within erotic or decorative beauty. For this exhibition, Chang is introducing the new installation Beautiful Instruments III (Breaking Wheel) (2014), which she has been planning for the last six years. A large white curtain is installed to demarcate a ‘sacred space’, which is occupied by twelve female performers sitting atop large wheels used on wooden carts in China during the 1950’s and 1960’s. The wheels were purposely chosen in accordance with their possible function as instruments for torture. Each performer sits on an unusual saddle studded with protruding crystals and a hole in the middle, where an attached feather rubs against the performer’s pubic region. Thus, while pedaling the wheels, the women are simultaneously subjected to both pain (from the crystals) and pleasure (from the feathers). During their arduous labor, the women sing a work song that combines two seemingly oppositional elements that might be interpreted as obscene. The type of melody used is known as the medieval Phrygian mode, which was actually banned by the church in medieval times for it was thought to represent decadence and debauchery. But the lyrics are from a traditional song that villagers in Eumseong, North Chungcheong Province in Korea have sung for generations while they labored in the arduous process of milling grains. Also, due to the shadows outside the sacred site, the entire work has covert and clandestine atmosphere. Through this odd combination of sacred ambience and a secular act, the museum becomes a site of transgression.

In the dialogue Gorgias, Plato uses the metaphor of thirst to demonstrate the close relationship between pleasure and pain. According to Plato, thirst is a type of physical pain, but that pain is alleviated when we drink, which thus gives us pleasure. Therefore, in the moment when a thirsty person drinks, he or she experiences both pleasure and pain. Pain and pleasure are two sides of the same coin, both of which serve to confirm our existence. Through her unique aesthetic language, Chang is able to effectively manifest our taboo desires, thereby allowing us to look upon our own latent instincts. By consistently pursuing topics that are difficult to represent, Chang Jia forces us to reconsider the concepts of art, thus presenting new possibilities that expand the perimeter of contemporary art.

The works of these four artists are immediately unique yet also reflective of some of the most compelling trends in contemporary art and society as a whole. Noh Suntag reveals imminent social and political events as symptoms of universal problems of humanity. Chang Jia utilizes the hidden discharges and desires of the human body to force us to confront our buried instincts. Koo Donghee peels back and rearranges the layers of everyday life to expose the absurdities embedded within. And Kim Shinil dissolves the boundaries of the widely held notions and concepts to express our fundamental essence as human beings. All of their artistic works resonate with the life and value of humanity. Walking through this exhibition, we discover more about ourselves and our present lives at this moment and also contemplate the deeper meaning of humanity and existence. I anticipate this exhibition to bring together the works of the four magnificent artists, help reorient the current position and direction while elicit new discourses in Korean contemporary art.