Moon Kyungwon • Jeon Joonho

Interview

CV

<Solo Exhibitions>

2014

His niche, GALLERY HYUNDAI, Seoul, Korea

2009

SCAI The Bathhouse, Tokyo, Japan

2008

Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, Paris, France

Arario Gallery, Cheonan, Korea

2007

Perry Rubenstein, New York, New York, USA

2004

Posco Art Museum, Seoul, Korea

2002

11&11 Korea Japan Contemporary Art 2002(Traveling Exhibitionn),Gallery 21+Yo, Tokyo, Japan

2001

“Tomorrow’s Artist”,Sunggok Art Museum, Seoul, Korea

<Group Exhibitions>

2015

MOON

Kyungwon & JEON Joonho, The Korean pavilion, 56th Biennale di Venezia, Venice, Italy

2014

The 10th Anniversary Exhibition, Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

2014

The 5th Fukuoka Asian Art Triennale, Fukuoka, Japan

2013

Dream Society, Cultural Station Seoul 284, Seoul, Korea

2013

Multitude Art Prize, UCCA, Beijing, China

2013

If the World Changed,Singapore Biennale 2013, Signapore

2013

The 4th Lichtsicht Biennale, Bad Rothenfelde, Germany

2013

News From Nowhere: Chicago Laboratory, Sullivan Galleries of School of Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, USA

2013

Multitude Art Prize, UCCA, Beijing, China

2012

Kassel dOCUMENTA13, Kassel, Germany

2012

Gwangju Biennale, Gwangju

2012

2012 Korea Artist Prize, National Museum of Contemporary Art, Gwacheon, Korea

2011

Yokohama Triennale, Yokohama, Japan

2011

Haein Art Project, Haeinsa Temple, Hapcheon

2010

A Different Similarity, Kunstmuseum Bochum, Bochum, Germany

Powerhouse, Gallery Hyundai, Seoul, Korea

2010

Plastic Garden, Minsheng Art Museum, Shanghai, China

2009

Your Bright Future, LACMA, Los Angeles, California, USA

Your Bright Future , The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Texas, USA

A Different Similarity, Central Istanbul, Turkey

Moscow Biennial, Moscow, Russia

The 29th Biennial of Graphic Art in Ljubljana, Ljublijana, Slovenia

New Organ, Space C Gallery, Seoul, Korea

Imaginary Lines, do-Art, Seoul, Korea

2008

Modest Monument, Kings Lynn Art Center, UK

Meta Morphosis, L’espace LOUIS VUITTON, Paris, France

Busan Biennale, Busan, Korea

Nanjing Triennale, Nanjing, China

Peppermint Candy: Contemporary Art of Korea, The National Museum of Fine Arts,

Buenos Aires, Argentina

Von dem was dann noch bleibt, NKV Wiesbaden, Wiesbaden, Germany

2007

Contemporary Korean Art : Wonderlar, National Art of Museum China,Beijing, China

Peppermint Candy: Contemporary Art of Korea, MAC, Santiago, Chile

Have you eaten yet?: Asian Art Biennial, National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts, Taiwan

The 27th Biennale of Graphic Art in Ljubijana, Ljubijana, Slovenia

Asian Attitute, National Museum, Poznan, Poland

All About Laughter, Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, Japan

2006

Circuit Diagram, Cell, London, UK

Singapore Biennale, Singapore

On difference, Wttembergischer Kunstverein Stuttgart, Stuttgart, Germany

2005

Beautiful Cynicism, Arario Beijing, Beijing, China

The Fact Show “Critics Choice”, Foundation for Art & Creative Technology,Liverpool, UK

Images Festival, “Live Free or Buy”, Innis Town Hall, Toronto-Ontario,Canada

Shanghai Cool, Shanghai Duolun Museum, Shanghai, China

Post IMF, Art Ark Gallery, Shanghai, China

<Awards>

2013

Multitude Art Prize, UCCA, China

2012

Korea Artist Prize 2012, National Museum of Contemporary Art, Korea

The Noon Award, Gwangju Biennale Foundation, Gwangju, Korea

2007

Ljubljana Biennale,Slovenia

2004

Biennale awards, Gwangju Biennale, Korea

2001

The Tomorrow’s Artist, Sungkok Art Museum, Seoul, Korea

<Collections>

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, USA

Contemporary Art Society, London, UK

National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts, Taiwan

Uli Sigg, Switzerland

Heinz Ackman, Switzerland

National Museum of Contemporary Art, Gwacheon, Korea

Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

Gyeonggi Museum of Modern Art, Ansan, Korea

Daejeon Museum of Art, Daejeon, Korea

Amorepacific Museum of Art, Yongin, Korea

SBS (Seoul Broadcasting System), Seoul, Korea

- Moon Kyungwon

<Solo Exhibitions>

2010

GREENHOUSE, DoArt GALLERY HYUNDAI, Seoul

2008

BUBBLE TALK, Window Gallery (Total Museum, workroom, One & J Gallery, doART), Seoul

2007

Objectified Landscape, Gallery ARTSIDE, Beijing, Objectified Landscape, Sungkok Art Museum, Seoul

2004

Wins of Artist in Residence 2004, Fukuoka Asian Art Museum, Fukuoka

2002

Temple & Tempo, Kumho Meseum of Art, Seoul

<Selected Group Exhibitions>

2014

Future Perspective: 2084, Quadriennale Dusseldorf, Kunsthalle Dusseldorf

2013

Singapore Biennale, Singapore

Lichtsicht Biennale, Bad Rothenfelde, Germany

Sullivan Galleries , School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, USA

10th international Group exhibition, YCAM(Yamaguchi Center for arts and media), Japan

Multitude Art Prize, UCCA, Beijing, China

2012

Kassel dOCUMENTA(13), Kassel, Germany

Gwangju Biennale, Gwangju, Korea

2012

Korea Artist Prize, National Museum of Contemporary Art, Gwacheon, Korea

2011

Haein Art Project, Haeinsa, Hapcheon

Life, no Peace, only Adventure, Busan Metropolitan Art Museum, Busan

2010

A Silent Voice, Tokyo Wonder Site, Tokyo

A Different Similarity, Kunstmuseum Bochum, Bochum

2009

Beginning of New Era, National Museum of Contemporary Art_KIMUSA, Seoul

The 3rd Moscow Biennale: Focus on Korea-Contemporary Art, MARS Centre for Contemporary Arts, Moscow

2008

NOW JUMP, Nam June Paik Festival, NJP Art Center, Yongin

Modest Monuments, King’s Lynn Arts Centre, UK

2007

The 1st Asian Art Biennale: Have you eaten yet?, National Taiwan Museum of Fine Art, Taichung

2006

Fiction@Love/Ultra New Vision of Contemporary Art, Singapore Art Museum, Singapore

2005

Animate, Anime in Japanese and Korean contemporary Art, Fukuoka Asian Art, Museum, Fukuoka

2004

The 3rd Seoul International Media Art Biennale: ‘Game/Play,’ Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul

2003

Art Spectrum 2003, Leeum Samsung Museum of Art, Seoul

<Collection>

Fukuoka Asian Art Museum, Fukuoka, Japan

National Taiwan Museum of Fine Art, Taiwan

Monte Video, Netherlands

National Museum of Contemporary Art, Gwacheonm, Korea

Busan Metropolitan Art Museum, Busan, Korea

Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul

Gyeonggi Musem of Modern Art, Anshan, Korea

Kumho Museum of Art, Seoul

Jeju April 3rd Peace Memorial Hall, Jeju, Korea

Critic 1

Critical Dystopia: On News from Nowhere

Dr. Sook-Kyung Lee

Exhibitions & Displays Curator, Tate Liverpool

“The world is full of painful stories. Sometimes it feels as though there aren’t any other kind and yet I found myself thinking how beautiful that glint of water was through the trees.” – Octavia Butler, Parable of the Sower1

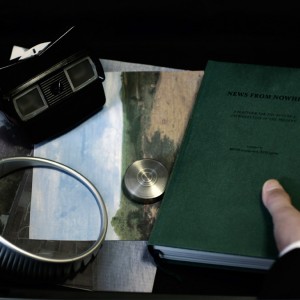

Titled as News from Nowhere (2012), MOON Kyungwon and JEON Joonho’s first collaborative project raises rather weighty questions on the current human condition and its uncertain future, and the role of art in the changing world. The title itself stems from artist and designer William Morris(1834-1896)’s literary work published in 1890, which explores socialist yet romantic ideals in art, life and labour. The story’s narrator William Guest wakes up from his sleep to a future society where there is no private property, no authority, no monetary or class system. Industrialisation and capitalisation didn’t take place in this utopian future, unlike the Victorian England Morris was living in, but people find pleasure in their work and in the nature nonetheless. Morrisian socialism appears to be moral outrage at capitalist exploitation and economic inequality, and the story reflects the author’s ambivalent critique on both capitalism and the authoritarian forms of the socialist doctrine of the time.2

MOON and JEON’s work explores the future as the symbolic reflection of the present in a similar manner, but their representation of the future is distinctly post-apocalyptic. Utopian scholarship and discourse often address the distinctiveness amongst the notions of utopia, anti-utopia and dystopia. Darko Suvin, for instance, defines ‘dystopia’ as “a community where sociopolitical institutions, norms and relationships between its individuals are organised in a ‘significantly less perfect way’ than in the author’s community… significantly less perfect, as seen by a representative of a discontent social class or fraction, whose value-system defines ‘perfection’. ”.3 On the other hand, Suvin articulates a different type of a dystopia, “which is explicitly designed to refute a fictional and/or otherwise imagined utopia,”, as ‘anti-utopia.’.4 MOON and JEON’s project in this sense conveys a dystopian vision to the future rather than a utopian or anti-utopian one, for it presumes the near extinction of human kind on the earth and the subsequent bleak survival yet reserves a room for possibilities. Rather than fully submitting to the narrative of apocalyptic future, the artists make us realise and confront the dystopian elements of our times.

MOON and JEON’s project is complex in its subject and its form, consisting of a film, a publication and a series of inter-disciplinary collaborations with architects and product designers. At dOCUMENTA 13 (2012) in Kassel, Germany, the work was presented as an installation with the two screen film projection alongside a separate room of architectural and design models that functions as the archive and the conceptual context of the wider collaboration.

The film, titled El Fin Del Mundo(The End of the World) (2012), shows the male and female protagonists on separate yet synchronised screens. The man is in a dimly lit room akin to an artist’s studio, clearly lacking essential things for survival such as food and water, let alone art materials. He comes back from outside with a trolley full of junks at one point, amongst them a dead white dog. While completing what seems like a sculptural assemblage, the man looks out of the window, sitting down in the sofa, and eventually and suddenly disappears from the room. On the other hand, the woman is in a pristine white room full of white lights and electronic equipment, dressed in a white protective garment. Sorting and filing dead branches and dried up plants collected from outside, the woman gradually fills up a large wall in an orderly, grid like form, with these specimens. Somewhat disturbed by an unexplained presence, she wanders and finds a room next door that looks like the man’s last place. The spatial distance between the man and woman collapses at this point, and the temporal distance becomes more ambiguous than first appeared, due to the woman’s unexplained yet psychologically charged reaction to the man’s absent presence.

The film’s professional quality in performance, filming, mise-en-scène and editing is prevalent, and it ensures the viewer’s recognition of the particular lexicons of science fiction film genre. Part Blade Runner (1982), part 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and part Future Boy Conan (1978), El Fin Del Mundo(The End of the World) addresses several recognisable traits of dystopian storylines and characters distinctive in the sci-fi genre, such as a lone survivor in the midst of an apocalyptic disaster, authoritarian post-apocalyptic corporate power and predominantly absent yet momentarily resurgent humanity in the dystopian future.

Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev(1957-), the Artistic Director of dOCUMENTA 13, commissioned numerous new works from participating artists and MOON and JEON’s project is one of the new commissions. A multiplicity of themes, including siege, retreat, hope and stage, has been explored in this documenta, and the participants’ responses to these themes are also multi-faceted and thought-provokingly diverse. One recurring idea throughout the exhibition is, however, how art reflects and interacts with the world, in particular amid the violence of history, from the two world wars and the Vietnam War to the Arab Spring and the continuing conflict in Afghanistan. MOON and JEON’s project seems to successfully correspond to and enrich the themes of this year’s documenta, addressing not so distant issues of the apocalyptic world with a conscious emphasis on recent disasters and crises.

Looking at the dystopian future in literature and film is often linked with the desire for a better world, as mentioned earlier. A sense of critique against the grain of the grim economic, political, cultural and environmental climate is prominent in MOON and JEON’s project. Their decidedly practical and solution-focused approach keeps their project bound with possibilities rather than mere analyses, and it is their desire for change that is making the project relevant to what the collaborators and advisers have been doing in their fields even prior to the collaboration. The artists are not proposing clear solutions however, but they are creating opportunities for debates and discussions where alternatives and possibilities can emerge. In other words, the project not only evokes awareness but also encourages us to confront the dystopian reality so we can work through them and begin again. MOON and JEON explain that “Sci-fi is always the fable of the present. By employing the way to look at the future instead of the present, we wanted to address current issues, especially in relation to what art is and what art could be.”5 It is particularly interesting that they are raising questions of art in relation to the utopian/ dystopian paradigm, since the extreme nature of their imaginary future seems naturally bound with wider socio-political issues such as natural or man-made disasters and their impacts on human existence. The artists’ questions are, however, closely linked with the condition of human existence, since they assume that the meaning and role of art will remain to be the key questions for human beings even in the most extreme conditions, like the end of the world. ‘The end of the world’ is in fact ‘the extinct of the human kind’, but they do not yield to a mere critique of the world as it stands and is becoming, but attempt to remind and convince us what makes human beings as ‘human’ – desire to create and appreciate art.

MOON and JEON continue, “We realised from early on that such questions couldn’t be answered easily and we began a search for people who might shed lights on these difficult questions. Talking to people from different fields and disciplines, like poets, film directors, scientists, designers and architects, we realised getting away from the inner circle of visual art was a great way to find a wider understanding of art.”6 The publication of the project, News from Nowhere: A Platform for the Future & Introspection of the Present (2012), includes a number of contributions and interviews with collaborators and advisers.7 Contributors range from architects and film directors to philosophers, musicians and scientists, such as Lee Changdong(1954-), Yusaku Imamura(1959-), Go Eun(1933-), Toshi Ichiyanagi(1933-) and Hans Ulrich Obrist(1968-), and they examine the present and envision the future in relation to their specialist areas in their chosen ways.

The artists’ collaboration with architects and product designers such as MVRDV, Toyo Ito(1941-) and Takram Design Engineering has a particular benefit in making the project firmly rooted in the real, present world. Presented in a room adjacent to the screening area, the installation titled Voice of Metanoia (2011-12) functions as an archive. Futuristic lifestyle products, technologically advanced clothing and reconstruction models for Japan’s Tohoku area are included, reflecting the collaborators’ interpretation of the thesis suggested by MOON and JEON and proposing several versions of alternative futures. Whereas the question of art could be seen as an abstract effort, ideas attached with inherent functions seem tangible and utilitarian, however remote or stretched these ideas are from the current reality. The recent earthquake and tsunami in Japan and the on-going financial crisis on a global scale bring pertinent background and necessity to their ideas for alternative ways of living and thinking. It is not surprising to learn some of the design ideas are already in use in post-disaster Japan, as seen in the architecture project by Toyo Ito, and it makes us wonder if and when these ideas will become genuine solutions rather than hypothetical ones.

Since its first issue in 2010, MOON and JEON’s online ‘newsletters’ have closely followed the development and progress of their project.8 In sixteen volumes so far, their newsletters explored the artists’ initial ideas for the film and book projects, while recording their meetings and conversations with collaborating artists and advisers. These collaborators and advisers also participated in the artists’ seminars and workshops in the past two years exploring various issues related to the project. The generosity in spirit and time these participants have devoted throughout the process demonstrates their strongly shared concern for the deteriorating world and its urgency. There seems to be a common acknowledgment for the need for interdisciplinary collaboration amongst them, since the issues and crises we are confronting are not limited to individual disciplines but extensively interconnected.

The overall tone of News from Nowhere project is inquisitive and indeterminate. It is still possible to discern some characteristics of MOON and JEON’s individual practices, notably MOON’s meditative take on the formal language of lens-based art and JEON’s critical view on the system of art and its power relations. However, they seem to have resolved the conceived difficulties in artistic collaboration, against the conventional perception of artistic production as fundamentally individual endeavour. The nature of the project as an interdisciplinary collaboration is undoubtedly a factor for ensuring such collaboration beneficial. Postponing answers and definite positions in the process of integrating two individual artists’ views also appears to have had positive effects in this particular project. As Lee Changdong claims in a conversation with the artists, “art or the act of creation is not about providing answers but about asking questions. Answers should be arrived at by the individual. Providing an answer, even believing that there is an answer, is not an artistic or creative endeavour.”9

MOON and JEON’s project resonates with what Lyman Tower Sargent(1940-) termed as ‘critical dystopia.’.10 It re-functions dystopia as a critical narrative form that reveals the inability of current discourses to correct the world and proposes new ones that contemplate possibilities, choices and therefore hope. Such progressive possibilities are inherent in dystopian narrative, and MOON and JEON have now provided us with a platform for suggesting a better vision for the future with the News from Nowhere project. Demonstrating utopian longing in current cultural and socio-political situation, the project opens up many possibilities for further exploration of utopian dimensions beyond the dystopian present.

1. Octavia Butler, Parable of the Sower, (New York: Warner, 1993), §21:235-36

Butler, Octavia, Parable of the Sower, (New York: Warner, 1993), §21:235-36 ?

2. See Anna Pavinskaya, “Janus-Faced Fictions: Socialism as Utopia and Dystopia in William Morris and George Orwell”, Utopian Studies, vol.14, no.2, 2003, pp.83-98

Vavinskaya, Anna, “Janus-Faced Fictions: Socialism as Utopia and Dystopia in William Morris and George Orwell,” Utopian Studies, (March 2003), pp. 83-98

3. Darko Suvin, “Utopianism from Orientation to Agency: What Are We Intellectuals Under Post-Fordism To Do?”, Utopian Studies, vol.9, no.2, 1998, p.170

Suvin, Darko, “Utopianism from Orientation to Agency: What Are We Intellectuals Under Post-Fordism To Do?,” Utopian Studies, (December 1998), p. 170

4. Ibid.

5. From several interviews with MOON and JEON, between August 2011-June 2012.

6. Ibid.

7. Mediabus, Workroom, LEE Sunghee ed., News from Nowhere: A Platform for the Future & Introspection of the Present, (Seoul: Workroom Press, 2012)

8. See www.newsfromnowhere.kr

9. MOON and JEON, “Reality and Illusion: the 2nd Conversation with Director Lee Changdong,” Newsletter 7, www.newsfromnowhere.kr

10. Lyman Tower Sargent, “The Three Faces of Utopianism Revisited,” Utopian Studies vol. 5, no.1, 1994, pp.1-37

Sargent, Lyman Tower, “The Three Faces of Utopianism Revisited,” Utopian Studies, (June 1994), pp.1-37

Critic 2

In Praise of The Loss of Limited, Weighty, Orientated Body-Space

Chus Martinez

I.

“Film”, wrote Edgar Morin, “shows us the process whereby man penetrates the world and the world inseparably penetrates man” at a specific point in a dialectical transitional foreground that acts to bring about a transformation. However, this foreground is nothing but the image itself, the image as it “is not simply the threshold between the real and the imaginary, [but yet] the radical and simultaneous constitutive act of the real and the imaginary1”. If the man of film really is the imaginary man that Edgar Morin suggests, it is certainly not the case that we go and only assess men who flee and men of illusion, men of the unreal and men of ignorance, apolitical men and men indifferent to the world.

The world penetrates woman and men, a world that underwent a radical transformation that came to and end and is now searching for a new beginning. Such is the departing hypothesis of the work of Moon Kyungwon and Jeon Joonho. The world conclude and reestarts again in a complex film that is actually a passage, the locus where the many elements that conform the construction of a new world, interact. Their work needs to be understood as an speculative exercise. A proposal to understand time and space differently, to establish new forms of connectivity between language, dreams, reality, the subjects, the group.

Their film and their complex installation proposes a series of homologies for the three time-substances, or states of matter: the solid, the liquid and the volatile worlds. The project proposes a sequences of transformations running from solid through liquid to volatile realities. A chain of mutations that correlates with a sequence which runs through the terms form, transformation and information. A first phase, the project involves the definition and manipulation of solids and substantives: the objects that inhabit the world, the individuals, the animals, nature…. A second phase concerns itself with verbs and actions: the language that is used to address this new coming world, the images that are produced for it, in it or throught it, even. Their work, and their is suppose to bring an expansion of categories and dimensions in film form, installation and even text to take account of the emerging topological conditions and sensibilities of the modern world, everything comes down to, or perhaps, rather moves through, prepositions, those intermediary or angelic parts of speech. Here a quote of Michael Serres on the matter:

Has not philosophy restricted itself to exploring – inadequately – the ‘on’ with respect to transcendence, the ‘under’, with respect to substance and the subject and the ‘in’ with respect to the immanence of the world and the self? Does this not leave room for expansion, in following out the ‘with’ of communication and contract, the ‘across’ of translation, the ‘among’ and ‘between’ of interferences, the ‘through’ of the channels through which Hermes and the Angels pass, the ‘alongside’ of the parasite, the ‘beyond’ of detachment… all the spatio-temporal variations preposed by all the prepositions, declensions and inflections?2

First there was the age of mechanics and geometry, the determination and manipulation of distinct forms. Then, in the age of thermodynamics inaugurated by Carnot and others, there is the generalisation of transformation, or the conversion of forms of energy: heat, light, movement, electricity, magnetism. Finally, there is the era of information, in which forms and forces give way to and even start to be understood as quanta of information. This sequence of typical states of matter parallels a sequence of different attitudes to or conditions of time, running from the reversible time of Newtonian equations, through the one-way, entropic time of the second law of thermodynamics, to the negentropic, or sporadically reversible time of chaos theory.

II.

“Aren’t we living in a world were headless man only desire decapitated woman?”

“Aren’t we living in a world” –the poet says full of empathy for himself- “where headless man only desire decapitated woman? Isn’t a realistic vision of the world the emptiest of illusions? Aren’t your son’s childish drawings much more truthful?” The sentence is said by Jaromil, the protagonist of Life is Elsewhere by Milan Kundera, a passionate supporter of the 1948 Communist revolution in Czechoslovakia and, not incidentally, a lyric poet. There is a natural affinity, it seems, between revolution and lyric poetry: “Lyricism is intoxication, and man drinks in order to merge more easily with the world. Revolution has no desire to be examined or analyzed, it only desires that the people merge with it; in this sense it is lyrical and in need of lyricism”

He is one of those individuals that prefer wet to dry eyes, that talk to the hand close to his heart and despised those who keep them in their pockets. He, the young poet living on the edge of times transforming, embodies the syntactical mode of addressing the world coined by André Breton: “beauty will be convulsive or will not be at all”. Radical or nothing, transparent, readable like the tears indicating that the man is feeling, like the open expressing a desire of embracing the world and making it a home, real like the people, not marvelous, immediate not erotic. Hannah Arendt’s claim that, “what makes a man political is his faculty of action” seems undeniable. Who would be in favor of the ugly idea of non agency in times or urgency, who would not see a danger in those who in the name of privacy, or withdrawal, would privileged a sense of autonomy and then, perhaps, keep their hands in their pockets, or just move the eyes from the crowd, elsewhere. But how to understand what it seems a disparate for the commonsense, that is, that action could be somehow understood as a faculty separated from the realm of the “empirical society”, a term used by Adorno, the real where all seems to have a direct consequence, where revolution coincides with a growing awareness of its inability to change the social, where powerlessness just becomes the privileged object of a guilty self-reflection, that in its turn has marked the re-foundation of a new twist of critical thinking. Art’s and culture’s reflexive preoccupation with its own powerlessness and superfluity is precisely what makes it capable of theorizing powerlessness in a manner unrivaled by other forms of cultural praxis. However, to become one with the exercise of describing one’s own position, with the rehearsal of the despair provoked by restricted action, seems a sad near future.

Where to look then? Do we need a prophet of unfeelingness, as Carl Gustav Jung called James Joyce? About this, he wrote: “we have a good deal of evidence to show that we actually are involved in a sentimentality hoax of gigantic proportions. Think of the lamentable role of popular sentiment in wartime!… Sentimentality is the superstructure erected upon brutality… I am deeply convinced we are caught in our own sentimentality… it is therefore quite comprehensible that a prophet should arise to teach our culture a compensatory lack of feeling”. Prophets aside, his words open a different space between passivity and action, making the un-feeling as a different way of acting, moving away from the paranoia that interprets the lack of movement, of the immediate release of a sentiment ignoble.

And therefore, this need for a new men, a new woman, a new real, a new future in the work of Moon Kyungwon and Jeon Joonho needs to be seen in conjuction to this lyrical crisis, in conjunction with the limit of the relationship between emotions and our future political life.

III.

But the inexpressive, the inert, the unnervingly passive poses many problems to our Modern understanding of the political. The hand in the pockets in terms of revolt, the lack of “movement” –action- is perceived as ambiguous, as equivocal because it is in the antipodes of our will of synchronizing with “our times.” The dysphoric provokes antagonism, it is not there, with the rest of us, it is not opening the private into the public, is keeping away a space that belongs to us, is not circulating the same information than the rest, is stopping the circuit, is not transparent. It is the negative pole of empathy. For the lyric soul, for those who “burn with indignation” while witnessing the over-all proliferation of injustice, the hands in the pocket, or just elsewhere, painting monochrom surfaces on canvas, for example, are often seeing as a form of ressentiment, why, otherwise, would not they engage with what needs to be done? Why would they pretend they are living in different times?

Even Foucault, who vehemently rejects the idea of a sovereign, founding subject, a subject capable to have experiences, t reason, to adopt beliefs, and to act, outside all social contexts, he preserve a form of sovereign autonomy under what he called the “agents.” In contract to the Modern misunderstanding of the autonomous subject, he defends that agents, in contrast, exist only in specific social contexts, but these contexts never determine how they try to construct themselves. Although agents necessarily exist within regimes of power/knowledge, these regimes do not determine the experiences they can have, the ways they can exercise their reason, the beliefs they can adopt, or the actions they can attempt to perform. Agents are creative beings –like Jaromil, lyric- and their creativity occurs in a given social context that influences it.

So, not even Foucault dared to go for those not “attempting to perform”. Foucault went even further, he argued that we are free in so far as we adopt the ethos of enlightenment as permanent critique. This is why we assert our capacity for freedom by producing ourselves as works of art. So we are again in front of a more complex, more eloquent form of lyricism, where the goal is, afterall, not only to be capable of producing sensuality of expression, but to become a sensual subject yourself.

So the problem is not only that we identify action with the vivid, with life and that we want to be part of it, seeing withdrawal as a form of enfeeblement, a defect in affection that makes individuals step away from the stream of life. However, the question of the lyric points towards something much more important, methodologically speaking. Towards something that surpasses the aesthetic dimensions of our well rehearsed ideological training: which is the possibility of conceiving time, historical time, as non-durational, and therefore breaking with our need not only to properly answer to what seems to be required by the force of the present, but also, with the nervous tic of wanting to represent it.

Insofar as the understanding of history means delineating a chronological axis upon which events are ordered, the sole task of the historian is to ceaselessly insert the stories that have not yet been included in that great continuous narrative. Meanwhile, the institution (where an exhibition is understood a way of institutionalising a material) is reduced to the place where the legitimacy of a right acquires a public form. The fact that the exercise of revision and the recovery of things forgotten provokes unanimous respect proves that a fitting vocabulary has been found, one that serves solely to avoid the unpredictable function of the experience of art.

Moon Kyungwon and Jeon Joonhos work directly addresses the political importance of recovery as a tactic, as being directly proportional to the impossibility of formulating a more complex statement of the relationship between contemporary art and a discontinuous conception of time that is expressed in rhythms and cannot be represented as duration. In other words, a way of understanding time that is indifferent to the idea of progress and is therefore relieved of the imperative of innovation. This understanding of time has no qualms about repetition, about imitating what has already taken place. Generating doubt about these constant reincarnations and about the spontaneity of the contemporary would provide a way around the supposed sincerity with which it is believed that art and culture –but not, for instance, science– must speak.

Their film, as well as the complex installation is the result of a dialectical interplay between great narratives and academic appendixes, the past and history are manifested as a new facet of culture and of its present power: this is not the power to delve into adventures of logic that might lead to a new episteme, but rather the de facto ability to include or exclude. Nonetheless, this explosion of voices and points of view has contributed to maintaining a degree of confidence in public opinion thanks to the constant effort at ceaseless expansion implied by historiographic revision and its relationship to contemporary art. The worst enemy of the enthusiasm inspired by the possibility of intervening on, interrogating, interfering with, modifying, amending, taking back and affecting hegemonic narration is the tendency to endlessness. Each footnote serves to both clarify and to obscure in a new way, one that rather than providing a new consciousness of the issue at hand or of contributing to an understanding of the relationship between contemporary art and time, between production and the inextricable complexity of the contexts in which it appears, places us before endless windows through which we peer –always under the promise of completing history. We can assume the risk that disconcertion brings. What is harder, though, is to face the fact that there are those who attempt to replace this strain of research not by adopting another logic but by emulating this effort and reducing it to a mere gesture that credibly illustrates the choreography of this explosion of histories within history.

IV.

How to find a way out of this melodic way of understanding history without losing sight of rigor or responsibility? The “null,” that which seems to have strayed from meaning –idiocy, nonsense– merits our attention as never before. In these forms of absentmindedness lies a new imagination of the private, a way of resisting the power of empathy in all its strains, whether real or virtual. Mistrust of a thoroughly defined present allows a part of artistic intelligence to elude the desire for art and institutions to be able to respond eloquently to their times. In other words, it allows an escape from responsibility understood as the imposed need to answer for, to clarify and not to expose ourselves to the exuberance and lightness of thought.3

And so is their work constructed, as a dream-like evasion that has as a goal to -in return- penetrate real life, to unmask it, to surprise our present with the dream of its own future.