OKIN COLLECTIVE

Interview

CV

http://okin.cc

<Selected Exhibitions/Projects>

2018

Toward Mysterious Realities, Total Museum, Seoul

2017

Reenacting History, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea(Gwacheon)

2017

Urban Ritornello, Ilmin Museum of Art, Seoul

2017

Dancers, Art Space Pool, Seoul & Gyeongnam Art Museum, Changwon, Korea

2017

do it 2017, Seoul, Ilmin Museum of Art, Seoul

2017

Video Portrait, Total Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

2017

In the Presence of Others, Korean Culture Center India, New Delhi, India

2016

The 3rd Nanjing International Art Festival-History Code: Scarcity, and Supply, Nanjing, China

2016

EAST ASIAN VIDEO FRAMES:SHADES OF URBANIZATION, Pori Art Museum, Finland

2016

Art in Society: Land of Happiness, Seoul Museum of Art, Buk Seoul Branch, Seoul

2016

Art Spectrum 2016, Leeum, Seoul

2016

Rien ne va plus? Faites vos jeux!, De Appel Arts Center, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDSs

2015

2015 Asian Art Biennale, National Taiwan Fine Art Museum, Taichung, Taiwan

2015

Survival K(n)it 7, Riga, Latvia

2015

Society of Choreography, Nam June Paik Art Center, Yongin, Korea

2015

EAST ASIAN VIDEO FRAMES, Pori Art Museum, Finland

2014

The 10th Gwangju Biennale-Burning Down the House, Gwangju, Korea

2014

Post-Movement: Night of Café Mueller, Kuandu Museum od Fine Art, Taipei, Taiwan

2014

Good Morning, Mr. Orwell, Nam June Paik Art Center, Yongin, Korea

2013

No Dance!: Between Body and Media, Zero One Design Center, Seoul

2013

No Mountain High Enough, Audio Visual Pavilion, Seoul

2013

Acts of Voicing, Total Museum of Art, Seoul

2012

Truth is Concrete, Steirischer Herbst 2012, Gratz, Austria

2012

The Forces Behind, Doosan Gallery, New York, USA

2012

Stop the City, Take the Street, Seoul Art Space Seogyo, Seoul

2011

Life, No Peace, Only Adventure, Busan Museum of Art, Busan, Korea

2010

Solo Exhibition, Concrete Island, Takeout Drawing, Seoul

2010

Solo Exhibition, Okin OPEN SITE, Okin Apartments Demolition Site, Seoul

2010-Present

Okin Internet Radio Station [STUDIO+82]

2009.7-2010.11

Okin Apartments Project, Okin Apartments, Seoul

<Selected Performances/Workshops>

2017

Instruction 2017-Like the duration of a rainbow, Ilmin Museum of Art, Seoul

2017

[Practice-03 Words and Location], National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, Gwacheon, Korea

2016

[Practice -02 Interlude], Youido Square/C-47 Airplane Exhibition Space, Seoul

2015

[Practice -01 Lung and Repetition], Nam June Paik Art Center, Yongin, Korea

2014

Operation-For the Beloved and Song, The 10th Gwangju Biennale, Gwangju, Korea

2014

Seoul Decadance-Live, Indie Art Hall GONG and rooftop, Seoul

2013

Mom-mal workshop, Art Space Pool, Seoul

2013

Playground in Island 2013, Workshop, Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia

2012

Don Quixote del Carre, Street Performance, Barcelona, Spain

2012

DJing-Korea Modern Superfine Affairs, Sound Performance, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea(Gwacheon)

2012

Operation-For Something Black and Hot, 19 Performance Relay, Seoul

2011

Operation-For Something White and Cold, Gallery Loop and Donggyo-dong area, Seoul

2010

5 Minute Revolution Manifesto, Nam June Paik Art Center, Yongin, Korea(Curated by Claudia Pestana)

2010

Jeju Human Rights Conference Workshop, Jeju/Seoul, Korea

<Selected Screenings>

2016

Exis-Experimental Film and Video Festival in Seoul, Korean Film Archive, Seoul, Korea

2015

ARTEFACT FESTIVAL 15, STUK, Ghent, Belgium

2015

The 15th Seoul International New Media Art Festival, Indie Space, Seoul

2014

Total Recall, Ilmin Museum of Art & Korean Film Archive/, Seoul, Korea

2013

The Spectacle and the detour of strategy, Guy Debord and Situationist International, media theater Igong, Seoul, Korea

2012

The 4thOffandFreeInternationalFilmFestival, Seoul, Korea

<Residencies>

2013

Incheon Art Platform, Incheon, Korea

2012

Hangar International Residency, Barcelona, Spain

2011-2012

Geumcheon Art Factory, Seoul, Korea

<Collections>

Seoul Museum of Art (SeMA)

National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea (MMCA)

Museum of Contemporary Art Busan (MOCA Busan)

Critic 1

Okin Collective: New Urban Design, Deployment, and Proposition of Apparatuses for Kinship Communities

Cho Ju-hyun (Chief Curator of Ilmin Museum of Art )

“Consider, then, the text given us by the existence, in the hindgut of modern South Australian termites, of the creature named Mixotricha paradoxa, a mixed-up, paradoxical, microscopic bit of “hair.” This little filamentous creature makes a mockery of the notion of bounded, defended singular self out to protect its generic investments.”1

1. Friends or Relatives? : Intimacy As Strangers

“What caused us to be excited in that moment? …… It was incited, associated with a more primitive death or disappearance. Perhaps it was solidarity among those who cannot be free from any humble birth or death, or the fear of death, and those who are not yet damaged, or indulgence in an enormous burial ground-playground that is not yet possessed by anyone.”2

The quotation above resembling a passage from a post-apocalyptic novel describing a world after the end of human civilization is from the monologue of artist Joungmin Yi who witnessed Okin-dong’s dreary, surreal scenes. Grayish cement debris of a building appallingly crumbling down as if being gutted by giant flames, ragged walls exposing a skinny steel framework, pieces of glass windows shattered and scattered on an earthen ground, and a futile, gloomy atmosphere hovering over this desolate, dreary site… The Okin Apartments Project (2009-2010) carried out by Okin Collective consisting of Joungmin Yi, Hwayong Kim, and Shiu Jin in July 2007 was a sort of happening executed by both artists and local residents who had unintentionally gathered together to cope with the unexpected situation of forced demolitions for a redevelopment project undertaken by the Seoul Metropolitan Government.

At this site with the invitation of Hwayong Kim who had resided there, Okin Collective’s member artists witnessed traces of life discarded by urban authorities who wielded tremendous power in a capital-centered modern society as they were ruthlessly being erased. The emotions they instinctually shared in such a disorganized, confused situation were a source of endless anxiety and an unknown sense of defeat which they felt while living in and enduring this era as “young” artists with “intimacy as strangers.” What is the meaning of solidarity among those who have voluntarily gathered together, run around the “enormous burial ground-playground,” and survived to form a heap of dead bodies? What can survivors do in a situation in which they have no future? What does these artists’ experience of a disaster scene predict?

The Okin Apartments Project, connotative of the narrative of a tremendous collapse or a devastating end in which people have no hope at all, save for the fact that they are alive, was in a context different from that of any common social or artistic practice or behaviorist artistic movement. The only action they could take in a world damaged by capitalism and with no more solutions was to “go together with strangers.” Internalizing despair and anxiety, they instinctually wrapped themselves up in their tentacles, infected others with their secretions, and formed an atypical group. Their solidarity was literally organic while using the title “collective” in some moments and not fixing its members or setting any specific target.

For over one year after they began to interfere in their neighbors’ affairs, the practices they executed with their colleague artists and the displaced residents were insubstantial party-like events such as playing a treasure-hunt game in waste materials around deserted apartments as if to sense the world through a children’s game; camping on the rooftop of an apartment building with invited residents; holding a sketch competition with colleague artists; and holding an impromptu performance at a demolition site. They occupied a place where every life form had been extinguished and provided neighbors whom they had never interacted with before with very unfamiliar experiences combined with something they had never imagined such as plays, travel, and exhibitions. By doing so, they came to develop an apparatus to unmask ideologies innate in the site and make residents aware of their own problems, after which they could assert and put their perceptions into action.

Okin Collective observes communities whose existence is not revealed or sensed as they are on the edge of our society. These communities’ “situation” instinctively causes individuals to form a group. Beneficial microorganisms are known to inhabit the bodies of many plants and animals. A recent study released by science journal Evolution Letters shows that intestinal microorganisms are parasitic on a host but have evolved into beneficial protectors when harmful bacteria attack the host. The host has also evolved to help more microorganisms inhabit its body. As advantages are maximized through the co-evolution of the host and the microorganism, they coexist in a symbiotic relationship, adapting themselves to each other.3

The fact that individuals who are strangers have evolved together in a situation in which they have to stand in solidarity against an external enemy leads us to reconsider the relations of communities that have been out of sight in our society. Around 2010 there was a noticeable increase in the number of small groups forged by artists of diverse fields such as visual artists, designers, and curators who have addressed art’s social practice in the Korean art scene. They commonly share “anxiety,” a legacy of our time undertaken by the younger generation.

Artists who had undergone Korea’s financial crisis in 2008 and young artists who had just entered the art scene at the time were consoled from their private solidarity with their “friends” with similar tastes and attitudes.4 As a result, they formed a bond of sympathy in a social situation damaged by capitalism and began their public discourse. All the same, solidarity with those who have “preferences and directions similar to my own” on which artist communities are based rests on the notion of a considerably solid boundary. In other words, they try to put emphasis on homogeneity in the name of “a friend,” but their communities are exclusive by nature and their solidarity is no more than an extension of biological classification after modern times. The fusion of the same kind suitable for crossbreeding brings about another type of alienation and has generic limitations. We cannot cope with any new diverse issues that arise in our society through solidarity with friends alone.5

On the contrary to this, those who have no power as subjects on the edge of society achieve evolution while “eating, infecting, being eaten, or being infected” by one another just as the seeds of plants germinate via infection under natural conditions.6 These are not based on exclusive relationships among friends, but on kinship relationships they have evolved through long-lasting intimacy primarily with strangers like new kinds of cells, organizations, and organs. Kindred things do not enter into relations with other things, but forge relationships that instinctively attach and tangle up with one another by spreading their tentacles.7 They form communities based on bonds that supersede preexisting ideologies while embracing true friendship and love across a register of bonds of intimacy.8 The ways in which Okin Collective has addressed communities over the last ten years vary. In the communities Okin Collective has observed, things occupy each other’s bodies and forge groups as “infective social relations” among very unfamiliar organizations and cells.

2. The City Trilogy : Being-Together

At this exhibition Okin Collective presents The City Trilogy addressing a few invisible communities primarily in Seoul, Incheon, and Jeju. They demonstrate the kind of social meaning solidarity among artists and rough, open communities can have in From the Outside (2018) which fragmentally documents the process in which the artist collective came into being. Their latest work titled In Search of How to Revolve and Its Reverse (2018) is an observation of a community of local artists living and working in the old downtown of Incheon. This documentary video featuring a community of local artists who live on the edge of the central art scene lays out the stories of those who have overcome dead-end situations in which their life force was exhausted. What can artists do where there is no base for their activities? How can their art be sustainable? The member artists of the artist community “Hoijeon Art,” the object of this work’s observation, vary in their origin, background, and age. The community consists of artists who have settled in this city in “a stuffed state where time stands still”9 and is comprised of a group of colleagues who have no choice but to meet together in a place where the artistic population is so small. Compared to a group whose members are forced by some ideology or share some consciousness, this group of artists spontaneously and instinctively came into being.

Utterly exhausted by inconsistent, irresponsible cultural policies carried out in the specific situation of Incheon, its bland disorderly urban systems, and policy-makers’ despotism and absurdity, those artists give testimony of the despair and sense of defeat they felt living in this hopeless city served as an opportunity to shape a unique community. Their only goal is thus rather to seek pleasure in a hopeless state in a place approximating “an enormous graveyard.” According to Jean-Luc Nancy, the moment humans are in existence together with others, depending on them, is when they realize that their existence is finite. To Nancy, a community is not a collection of separate individuals with the same beliefs and ideology but there is only an existential community or “being-in-common.” Defined as “the inoperative community,” this communal character refers to a state in which “I exist with other together.” “Inoperative” here means “inaction” producing nothing or letting something arrive. Characterized by “singularity” as having no value, each individual in a community can be complete only in the boundary where the individual comes across another singular being, the other’s skin (or heart). This refers to a state in which I am entirely myself and simultaneously can be the other: divided and sharing with one another (partage).10

The artists of Hoijeon Art lends meaning to their announcement that they rotate together to explore their identity as artists while living their own life. Their revolution is either a meaningless idling rotation or rotation together with others. Gestures from martial arts as “vain, useless technique,” the main apparatus Okin Collective adopted in their series Operation also convey an important message in this work. As in demonstrations by a master of martial arts, “rotation” is a technique (apparatus) to sense the moment in the subconscious. The meaning of “rotating” together contains the potential for a new condition in which the artists of Hoijeon Art dominate others with ease using the center of gravity abruptly arising when they rotate together in one direction as well as the potential moment in which their rotation works as both action and reaction in a powerful whirlpool. Even though that is idling, this movement enables their bodies to be balanced and to prepare for the next revolution. While exploring other lives outside art, they become able to create a sustainable situation in which they keep rotating, touching others’ skin (or heart). This “community of finite beings” manifested only when its artists are together as shared beings has its own distinction, appearing as “something to come up” in an unstable state.

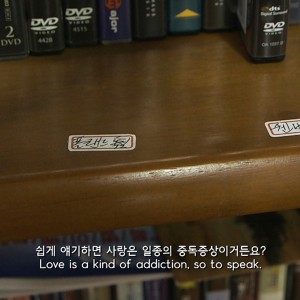

Casa d’Or (Golden House)(2017), one of the city trilogy, is a documentary video that is the result of observing the lives of old people conscious of “death” and a community of senior citizens. The coffee shop Casa d’Or located at the original center of Jeju is a community space that functions different from those of common coffee shops. This old café whose interior design appears archaic is a place where the elderly of this region spend their time listening to classical music. The decent elders sitting around a TV monitor have a friendly talk while watching an opera performance of The Tragedies of Sophocles in Japan. What do the elders enjoying the high-brow culture of classical music commonly feel? An old gentleman who worked as the director of a medical center in Jeju for 18 years mentions that both money and relationships with friends and family members are meaningless for one who is on the verge of death. An elder who worked as a pastor raises some significant issue pertaining to Casa d’Or. That is elders have something in common, moving beyond some secular conditions such as educational background, social status, gender, and power. This community is associated with the emotional solidarity available for a kinship community by embracing others as part of themselves with their instinctive sense before life and death instead of some social conditions used to distinguish themselves from others and create vertical boundaries.

The community of the elders the Casa d’Or Okin Collective observed seems to show evidence that humans cannot form a veritable community without the perception that they are finite beings. At the same time, it could be an example of a group inspired by a new sense of aesthetic community Nancy mentioned. Casa d’Or, a community formed by a common interest in art is a group shaped through a process of deconstructing human identity after mutual identification. A community stimulated by the senses is forged based on “sharing the sensuous,” breaking away from the preexisting social divisions. In the process of subjectifying its members, the community works on the premise that all humans are equal. In this sense, it makes the arts working as the medium of this community have a true political effect. In this video, Casa d’Or or Golden House, a dialogue of female senior citizens reminds one of a gender community placed on the polar opposite of public order in dichotomous logic. They worry about how to clean their space while appreciating an opera.

Okin Collective shaped through their concerns over urban issues when intervening in the process of demolishing the Okin apartments has banded together with diverse invisible subjects in society such as workers, sexual minorities, old men, and minor persons. Dedicated to recreating the relationships destructed by modernity in present time, they make forays into sharing difficulties to recover a destroyed haven. They are neither themselves nor others but either us all or countless beings in Okin.

3. Apparatus-Fiction, Apparatus-Community

Okin Collective forged communities over the last ten years by unmasking ideologies adopted by power in our society, regarding not only their own community but also other diverse communities as an apparatus. In general, an apparatus is a kind of equipment commonly used to achieve a particular objective, like mechanical equipment. Inevitably accompanying power (strength), those who possess an apparatus are able to control any national and social system. The apparatus concept referring to the system in which power relations strategically operate has been scrutinized from various angles by modern thinkers of the late 20th century such as Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida, and Giorgio Agamben. Foucault discusses the point in which the operation mechanism of the apparatus “has a strategic function as the nature of the connection point between plural elements” through the concept of “dispositif” clarifying that the apparatus ultimately “poses questions concerning a ‘fixed’ power or system and is able to work as fluid power to overturn this.”11

That is, one who decides where to arrange is a determinant of meaning. The apparatus mechanisms such as the arrangement or deployment of artworks by the museum or gallery curators or the manager’s control mechanism that has subordinated the general public to specific ideological effects were adopted for the disclosure of social and economic systems by artists of minimalism and were critical of institutions in the mid-20th century. This is because a place for art is more than just a space—it is where ideological effects are entailed and works as a systematic frame involved in a power game.

Okin Collective has paid heed to the possibility of working as an apparatus in the reality they face and in the situation in which art cannot function properly in society. At the same time, they have tried to turn their place of art, collective, and invisible organism into a relational network to disclose various issues and interests pertaining to society, culture, the economy, politics, and the institutions around them, forming solidarity with those who are on the edge of society and confronting a very solid apparatus like the social system. The apparatus mechanism conceived through Okin Collective’s diverse projects is intended to create “a stage dominated by reality.” It is in the form of the theater as a sort of post-drama, becoming both art and a political act.

Okin Collective’s Seoul Decadence-Live (2014) is a performance that reconstructed 9-Day Hamlet, a play performed by workers fired from Cort Guitar (Korea’s largest guitar manufacturer) after a factory closed in Seoul. These workers who have been involved in a variety of cultural activities including music, band, and theater over the course of 11 years while struggling for their reinstatement against unfair dismissal tried to bring their situation to the public eye by adapting Hamlet for a play in which they starred. Okin Collective casted co-directors of the play Vibrating Jelly (Eun-young Kwon and Mae-un-kong) when restaging this play as a performance. The play was turned into a sort of improvisational theater piece after the directors gave the nervous amateur performers advice which enabled them to candidly draw out their feelings.

Okin Collective’s performances are particularly marked by their amateur performers who have no formal professional training. Performers as well as audiences are physically present in the theater whose stage is not clearly separated from its auditorium. A new sense of solidarity is formed between the stage and the auditorium. This stage of reality Okin Collective has created aims to make it difficult to distinguish fiction from reality and is not made to perceive a staged situation as an actual one. That is to say, the stage of reality displays its effect with the ambiguity of a theatrical situation. The directors on stage who assume an unusual role present a situation in which the audience cannot judge if the person letting out a painful cry is speaking Ophelia’s lines or telling a worker’s personal story. In this way the audience takes part in their performance by being in a situation in which they do not know whether it is real or part of a play. The property of a fictional play is overlapped with that of an actual political rally in such a performance. Viewers are confused by these two different frames when they collide and are turned into performers in the theater. The apparatus of performance Okin Collective has conceived has subversive power in the boundaries between art and non-art through an exquisite combination of fictiveness and reality and a reversal of the relationship between the performer and the audience.

Recently at do it 2017, Seoul held at the Ilmin Museum of Art, Okin Collective executed a performance based on its reinterpretation of Pierre Huyghe’s instruction and turned the venue into an apparatus. Conceived from the instruction “Like the duration of a rainbow,” this performance seemed to highlight issues pertaining to homosexuality, gender, and minorities. Serving as an opportunity for participants to “view the exhibition with their companion animals (plants or something),” the performance aimed to disturb viewers with an experimentally forged situation as an apparatus, engendering a subtle condition between the participants and viewers. Unlike other projects akin to it, however, this performance did not bring about any particularly extreme confrontational situation. Rather, the viewers visited the museum dressed depending on a given dress code with their companion animals such as puppies, turtles, or parrots or even their favorite plants adorned in rainbow colors and enjoyed the refreshments and gifts offered by the artists. As each visitor is an antagonist of the performance, irrespective of whether they are homosexual or heterosexual, they exist as what they are instead of acting as “themselves” from the other’s point of view. Preexisting contentious social issues apropos of homosexuality including queers and the resultant gazes intrinsic to them are diluted or removed due to the setting up of such a situation and a forum for universality where everyone can assimilate with one another and bring forth their own meaning.

Instead of being a performance predicated upon a well-woven scenario, Okin Collective’s stage of reality reflects an aspect that is far more real than anything else. Their performance can be discussed in reference to social psychologists who have conducted experiments with behavioral patterns between viewers and participants. When given such a less extreme scenario, both participants and viewers tend to concentrate on “the relation” between personal and collective actions and ultimately discover themselves. What do you feel and how do you act when you see a pink medicine bottle for panic disorder medication which is someone’s companion object, the back view of a lesbian couple, and your little turtle on the back of someone else’s big dog? As the performance itself works as an apparatus to measure ethical, social, and gender differences, measuring behavioral patterns not only points out human behavioral patterns in ethical and social terms but also causes both viewers and participants to connect to the mechanism that serves to experiment with “the only emotional state” somewhere between pleasure and clumsiness. Measuring such an emotional state is all dependent on individual experience. Each individual who connects to this mechanism opens up possibilities to act from their own position and change arrangements and rearrangements.

4. Epilogue

Okin Collective does not present a theatrical stage involving some climax through their apparatus-fiction. They also do not depend on a meticulous scenario to change a viewer’s perception. The stage of their practice is not the theater but life itself. Theatrical fictiveness does not vanish into reality but is, rather, reinforced by reality. After all, the stage Okin Collective has constructed and arranged makes invisible people and rules visible by completely blurring any boundaries. It thus enables viewers to see reality by changing their point of view.

As Franco Bifo Berardi argued, exhausted humans left behind in this era “after the future” when capitalism exists in the way “it mobilizes spiritual energy necessary for creative labor”12internalize a dominant mood of gloom and futility. The practices Okin Collective has carried out over the last ten years were to create a stage dominated by reality and to deploy, arrange, and reconstruct the apparatus to face reality through solidarity with those who have managed to survive in this age of collapse and disintegration. In a sense, they might be political, philosophical, and ecological experiments which the art of our time is able to conduct at the largest scale possible.