Lim Minouk

Interview

CV

2015

FireCliff5, Minouk Lim solo exhibition, PORTIKUS, Frankfurt, Germany(upcoming)

Minouk LIM solo exhibition, PLATEAU, Seoul, Korea (upcoming)

From X to A, Community-Performativity Project, Asia Culture Complex, Gwangju, Korea

2014

Navigation ID, 10th Gwangju Biennale, Korea

Monument300_Chasing Watermarks, DMZ Peace Project, Cheorwon, Korea

2013

FireCliff 4_Chicago, IN>TIME Performance Festival, Logan Center for the Art, Chicago, U.S.A

Hyde Park Art Center Residency Program, Chicago, U.S.A

2012

Minouk Lim: Social Interstices-Between Images and Dispositif, iGong, Alternative Visual Culture Factory, Seoul, Korea

Minouk Lim: Heat of Shadows, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, U.S.A

FireCliff 3, Collaboration with Emily Johnson, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, U.S.A

2011

Perspective, Freer/Sakler Gallery_Smithsonian Museum, Washington D.C, U.S.A

Liquide Commune_Minouk Lim, PKM Gallery, Seoul, Korea

FireCliff 2, Festival BOM, Baek and Jang Theatre of National Theatre Company of Korea, Seoul (site specific performance)

2010

FireCliff 1, Art is Action=Action is Production, A project for La Tabacalera, Madrid, Spain (site specific performance)

Horn and Tail, Gallery Plant, Seoul, Korea

2009

S.O.S-Adoptive Dissensus, Festival BOM, Seoul, Korea (Theatrical site specific performance)

2008

Jump Cut, ArtSonje Center, Seoul, Korea

<Selected Group Exhibitions>

2015

The Time of Others, Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo, Japan (Upcoming)

2014

The Future is Now, MAXXI National Museum of XXI Century Arts, Roma, Italia

Thoughtful Hands, KIM Geun Tae Memorial exhibition, DDP, Seoul, Korea

‘Oh My Complex’, Total Museum, Seoul, Korea

‘Borders and Border Crossing’, Pohang Museum of steel Art, Pohang, Korea

2013

‘The Shadow of the Future:7 Video Artists from Korea’, National Museum of Contemporary Art Bucharest, Romania

‘Act of Voicing’, Total Museum, Seoul

‘Corea Campanella’, Hotel Amadeus, Venice

‘Brilliant Collaborators’, Ilmin Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

2012

‘Korea Artist Prize’, National Museum of Contemporary Art, Gwacheon, Korea

‘Sounds like Work’, Kiasma Theater, Helsinki, Finland

‘Acts of Voicing: On the Poetics and Politics of the Voice’ Württembergischer Kunstverein Stuttgart, Germany

Oh, My Complex,Württembergischer Kunstverein Stuttgart, Germany

Mind the System, Find the Gap, Z33, Hasselt, Belgium

Intense Proximity, Paris La Triennale, Palais de Tokyo, Paris

Korean film Festival, The Smithsonian’s Museum of Asian Art, Washington D.C

What should I do to live in your life?, Sharjah Art Foundation, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

How Physical, Yebisu International Festival for Art and Alternative Visions, Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography

2011

Countdown, Culture Station Seoul 284(Former Seoul Station), Korea

Burn What You Cannot Steal, Gallery NOVA, Zagreb, Croatia

City Within the City, ArtSonje Center, Seoul, Korea

Community without Propinquity, MK Gallery, Inheritance Projects, London, UK

Melanchotopia, Witte de With, Rotterdam, Netherland

Experimental Film & Video Festival in Seoul, Indi-Visual, Seoul Cinematheque KOFA, Korea

Hit&Run Project, Myungdong Cafe Mari Front Liberation, Seoul, Korea

Black Sound White Cube, Haus Bethanien Studio1, Berlin, Germany

Places, Issue Section, 13th International Women’s Film Festival in Seoul, Artreon,Korea

Featuring Cinema, Gallery Space C, Seoul, Korea

2010

Mouth to Mouth to Mouth’Five Korean Contemporary Artists, Salon of the Museum of Contemporary Art Belgrade, Serbia

Touched, Liverpool Biennial 2010, FACT, Liverpool, U.K.

Platform 2010, Projected Image, Art Hall, ArtSonje Center, Seoul, Korea

Rainbow Asia, Seoul Arts Center, Hangaram Art Museum, Seoul, Korea

Perspective Strikes Back, L’appartement 22, Rabat, Morocco

Trust-Media City Seoul 2010, Gyeonghuigung SeMA, Seoul, Korea

The River Project, Cambeltown Arts Centre, Sydney, Australia

Griot Girlz, Kunstlerhaus Buchsenhausen, Innsbruck, Austria

Morality-Remembering Humanity, Witte de With, Rotterdam, Netherland

Random Access, Nam June Paik Art Center, Yongin, Korea

Move on Asia, Para/Site Art Space, Hong Kong

A Different Similarity, Bochum Museum, Bochum, Germany

2009

Perspective Strikes Back, Doosan Art Center, Seoul, Korea

Your Bright Future_12 Contemporary Artists from Korea, Los Angeles County Museum of Art / Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (November), U.S.A.

Unconquered, Museo Tamayo Arte Contemporaneo, Mexico

Everyday Miracles (Extended), San Francisco Art Institute (September) / REDCAT (November)), Los Angeles, U.S.A.

CREAM, Yokohama International Festival of Arts and Media, Yokohama, Japan

2009

Peppermint Candy-Contemporary Art from Korea, National Museum of Contemporary Art, Korea

Bad guys-Here and Now, Gyeonggi Museum of Modern Art, Korea

Text @ Media, Seoul Art Space Seogyo, Seoul, Korea (Lecture Performance)

A Different Similarity, Santral Instanbul, Turkey

(Im)migrants With(in), Open Space_Zentrum fur Kunstprojekte, Wien, Austria

Leisure, a disguised labor, Sinn Leffers, Hannover, Germany

Move on Asia_The End of Video Art, Gallery LOOP, Seoul, Korea

Socially Disorganized, Experimental Art Foundation, Adelaide Film Festival, Australia

2008

7th Gwangju Biennale, Annual Report, “On the road”, Gwangju, Korea

Invisible Cities, Toronto International Art Fair, Canada

Peppermint Candy-Contemporary Art from Korea, Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Buenos Aires (MNBA)

Cine Forum 4 : Digital Portfolio – 6 Views, Museum of Art Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea

Permanent Green, Isola Art Center, Milano, Italy

2007

An Atlas of Event, Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisbon, Portugal

Tina.B_The Prague Contemporary Art Festival, Prague, Czech

Anyang Public Art Project 2007, Anyang, Korea

Activating Korea: Tides of Collective Action, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Plymouth, New Zealand

10th International Istanbul Biennial, Turkey

Movement, Contingency and Community, Gallery 27 Kaywon School of Art & Design, Korea

City_net Asia2007, Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul

Peppermint Candy-Contemporary Art from Korea, Museo de Arte Contemporaneo, Santiago, Chile

PILOT:3 Live archive for artists and curators, Venice-Giudecca, Italy

Changwon 2007 Asia Art Festival, Sungsan Art Hall, Changwon, Korea

Something Mr.C can’t have….Korea International Art Fair, KOEX, Seoul, Korea

The 7th Hermès Foundation Missulsang, Seoul, Korea

2006

Somewhere in Time, ArtSonje center, Seoul, Korea

Public Moment, Artist Forum International2006, Seoul, Korea

6th Gwangju Biennale, The Last Chapter, “Trace Route”, Gwangju, Korea

Symptome of Adolescence, Rodin Gallery, Seoul, Korea

2005

Parellel Life, Frankfurter Kunstverein, Germany

Where is my friend’s home? Kunstlerhaus, Mousonturm, Frankfurt, Germany

Cosmo Cosmetic, Gallery Space*C, Seoul, Korea

Will you love me tomorrow, History of Women Exhibition Hall, Seoul, Korea

<Awards>

2010

The 1st Media Art Korea Award, Seoul, Korea

2007

The 7th Hermès Foundation Missulsang, Seoul, Korea

2006

6th Gwangju Biennale Gwangju Bank Prize, Korea

1995

Albert Rocheron Foundation Prize, Paris, France

Critic 1

Impossible thus Possible: The Philosophy of Minouk Lim

Lee Taek-Gwang

Prof. of Kyung Hee University and Cultural Critic

1. Testimony to Say ability

Minouk Lim is interested in that which is invisible. However, this does not mean her intention is to dismiss the visible and reinstate what is not. In other words, she does not adopt anti-representationalism, but instead attempts to ‘testify’ on behalf of what is invisible. This method is of considerable interest, since it appears as though what she intends to achieve is to pass beyond the arrangement of images in order to materialize ‘sayability.’ Such an interest in sayability is the thematic consciousness that runs through Lim’s entire oeuvre.

Therefore, what is important to Lim is ‘speaking.’ Her artworks consist of spoken words. They are sometimes stories, at other times incomprehensible mutterings, and at yet further times they appear as ear-splitting noises. As such, spoken words to Lim are invariable sounds. Sayability premises that some things are unsayable. That which is unsayable does not exist. Lim strives to take such things that are supposed to be nonexistent and makes them exist. How is this possible?

According to Giorgio Agamben(1942-)’s definition, ‘sayability’ is ‘the thing itself.’ Agamben states the following:

“The thing itself is not a thing—it is the very sayability, the very opening which is in question in language, which is language, and which in language we constantly presuppose and forget, perhaps because the thing itself is, in its intimacy, nothing more than forgetfulness and self-abandonment.”1

What is noteworthy in Agamben’s quote is that sayability is in apposition to ‘opening,’ as is ‘forgetfulness’ to ‘self-abandonment.’ At first, things are what can be expressed through language, but the moment they are rendered into words, they are excluded from language. For this reason, the thing itself is forgotten and consequently abandoned. What Lim’s art illustrates is this lingual exclusion itself. Speaking calls attention to the existence of the very thing thusly excluded.

Sayability is therefore the fundamental unit of existence. This is because if something is sayable, testimony can be given to its existence even if it cannot be seen. Collecting such testimonies composes the core of Lim’s work. As Walter Benjamin(1892-1940) once said, “The translation of the language of things into that of man is not only a translation of the mute into the sonic; it is also a translation of the nameless into name”2 As in the act of translation to which Benjamin refers, restoring those things excluded by human language back into the realm of language is exactly the underlying philosophical motive that can be discovered in Lim’s work. Following the precedent of Goethe(1749-1832), Benjamin defines works of art as ruins. To Benjamin, a text is similar to a ruin that offers testimony to an Ur-text that is no longer visible but had once surely existed. For this reason, the text of ruins can in fact be referred to as a testimony.

A thing itself is sayable because, without language, nothing can be communicated. In the end, even miscommunication is possible only through the medium of language. Therefore, misunderstandings arise regarding the things themselves. There are inevitable misunderstandings that arise from expressing the unsayable in words. In a way, this indicates that what has not been said is included in what has been said. In this context, sayability stems from the fragile medium of language, and this is what forms Lim’s perspective on communication.

2. Stories: Subjectification without the Subject

Doubting communication is an important issue for Minouk Lim. Her insight into the fragility of language is evidenced in Game of 20 Questions—‘The Sound of a Monsoon Goblin Crossing a Shallow Stream’ (2008) (henceforth Game of 20 Questions) and S.O.S.—Adoptive Dissensus (2009) (henceforth S.O.S). These two works deal with the idea of being able to freely express one’s thoughts and of being unable to say ‘no’. In Game of 20 Questions, words are fragmented into noise and devolve into a repetitive rhythm. The divided screen depicts the same space, but the words being sounded are of varying dimensions.

Here, the signifiers of multiple cultures acquire specific personalities. The characters are the signifiers. These signifiers are spoken entities, but also include what is not verbalized. This is why Game of 20 Questions seeks to uncover something to say, as if in a game. In Wrong Questions (2006), a work that deals with an agent excluded from language, a taxi driver who launches into an extended monologue has nothing at all to do with what he is saying. His words have been predetermined for him. Even the content is not about him, but about Korea. Here, what is being testified in this work is how words from a nation ultimately excludes and isolates the taxi driver.

Wandering about in search of a place to park, or to stay, is a citizen who longs to claim his or her own space. That is calling this citizen is the ideology that is being ‘testified’ through the taxi driver’s vocalization. However, there is no specific place for this citizen to reside. The taxi moves, and its location expands into the abstract space of a nation. Wrong Questions is an intriguing work that demonstrates how ideology speaks.

Lim appears to believe that what is important is less the elimination of ideology than making known the fact that an ideology is present. That is why, rather than arguing in favor of a post-ideological era, she opts to describe a story within an ideology. What she deems important is the storyteller. One might wonder why stories and storyteller are important. Why stories and the storyteller? Lim seems to regard stories from a similar perspective of Benjamin, who stated the following:

“The storytelling that thrives for a long time in the milieu of work—rural, maritime, and then urban—is itself an artisanal form of communication, as it were. It does not aim to convey the pure “in itself” or gist of a thing, like information or a report. It submerges the thing into the life of the storyteller, in order to bring it out of him again. Thus, traces of the storyteller cling to a story the way the handprints of the potter cling to a clay vessel.”3

Lim pursues the traces of a storyteller, which are like the handprints of a potter clinging to a clay vessel. What Lim offers in order to overcome reality in Wrong Questions is FireCliff 2_Seoul (2011), a performance in which a storyteller relates his experience of torture in the form of a story. The staging of an experience is perhaps the fundamental principle behind stories. FireCliff 2_Seoul does not simply accuse, nor merely report the facts of torture. By inviting the victim of torture on to the stage, Lim converts him into a storyteller. Of course, this characteristic is also evident in FireCliff 1_Madred (2010), through which the experience of working at a factory in Madrid is delivered through the alternative forms of stories and songs, completing an ‘artistic form of communication.’

This method is put to the greatest effect in International Calling Frequency (2011). As discussed above, Lim completely excludes the traditional form of language itself in this work. Of course, such exclusion does not indicate the elimination of language. However, by refusing to designate any one particular language, Lim attempts to unravel the individual held captive by her own identity. Those humming the tune are indeed distinct individuals, but they also constitute a network converted into a single international calling frequency. In this work, Lim’s story reaches the level of poetry. Of course, the resulting poem does not share the sensitivities of conventional lyrical verse. The poem is instead more approximate to what Alain Badiou (1937-) calls the ‘matheme of the event.’

Poetry offers testimony to the production of truth and secures that truth through being put into text. The poetic agent born through this process is the very agent of the truth that constitutes ontology. To Badiou, truth is an expression of the abyss. This abyss of existence is nothing but nothingness. Nothingness is a nonexistent cause, and in the end it is the traces of this absent cause that constitutes poetry. Therefore, poetry is invariably an example demonstrating the preceding absent causes. In other words, the poetic text is an expression of an event that occurs prior to the subject’s becoming. An absent cause does not exist, thus constitutes the paradox of an event. Badiou asserts the following:

“The paradox of an eventual-site is that it can only be recognized on the basis of what it does not present in the situation in which it is presented. Indeed, it is only due to it forming-one from multiples which are inexistent in the situation that a multiple is singular, thus subtracted from the state.”4

What makes this paradox of an event possible is the core of reality and truth. Like Jacques Lacan (1901-1981)’s notion of fantasy, the paradox of an event is a seduction in the direction of truth but simultaneously the cause of maintaining a certain distance from the truth. To Badiou, the relationship between truth and subject is composed by the axiom of infinity. As such, at the core of reality is emptiness. Badiou’s method is to name this empty core the void. Then what is void? According to Badiou, void is that which is excluded from an event that has settled as a situation. In plain language, events can be categorized into situations and states, where a state is a permanent rendition of a situation. That is, situation minus void equals state. In this context, an event never has any choice but to remain a ruin.

3. The Flâneur at the Ruin

The ruins that appear in the works of Minouk Lim are traces of events. What Lim works to show is a situation in which an event has been reduced to state. The sentiment of anger emanating from New Town Ghost (2005) later appears to have acquired a further dimension in Portable Keeper (2009). The man toting the ‘keeper’ all over a construction site looks like a parody of the flâneur, or stroller, who wanders about in the city making roundabout tours. Labeling a painter named Constantine Guys as a flâneur, Charles Baudelaire claimed that Guys was an artist who embodies a certain quality that can only be referred to as modernity. Baudelaire’s image of ‘flâneur’ overlaps to a certain degree with that of the man in Portable Keeper. Regarding the flâneur, Baudelaire made the following statement:

“The crowd is his element, as the air is that of birds and water of fishes. His passion and his profession are to become one flesh with the crowd. For the perfect flâneur, for the passionate spectator, it is an immense joy to set up house in the heart of the multitude, amid the ebb and flow of movement, in the midst of the fugitive and the infinite.”5

Baudelaire is indicating that taking leisurely strolls in the city streets is a characteristic of modern art, or of modern poet. Of course, this sort of stroll is without a point of destination and is different from what is commonly called a ‘walk’, which is taken deliberately as exercise. The stroll represents the 19th century Parisian culture which considered turtle-like sauntering to be elegant. To Baudelaire’s flâneur, taking a stroll is a condition for his existence, and is closely related to the crowd. The flâneur is a person who collects plants in a field of asphalt.

What caused the flâneur, as Baudelaire detailed, to appear in 19th century Paris? Benjamin points to the passage, or the arcade, as what induces the leisurely footsteps of the flâneur. The arcade was a most suitable place for leisure strolls. It was Baudelaire who elevated the status of the flâneur from a wandering idler looking around the arcade to that of a poet.

Baudelaire defined the flâneur as the modern poet, or in other words, as a manner of existence for modern artists. From this definition, what is the truth that can be read? The flâneur can indeed be considered someone who demonstrates the evolution of artists’ mode of existence in the face of modernity. In this respect, the flâneur is closer to a collector than to a poet for Benjamin, and this point is what distinguishes Benjamin from Baudelaire. Benjamin viewed a street as a place of residence for the collector. In such a site, the flâneur of Benjamin, unlike that of Baudelaire, does not compose a poem but instead collects something and then produces knowledge:

“That anamnestic intoxication in which the flâneur goes about the city not only feeds on the sensory data taking shape before his eyes but often possess itself of abstract knowledge—indeed, of dead facts—as something experienced and lived through. This felt knowledge travels from one person to another, especially by word of mouth.”6

As it is understood here, the flâneur is a producer of new knowledge as a modern poet. However, the flâneur does not belong to the system of division of labor evinced under Capitalism. The flâneur is more an artist than a laborer. The flâneur endeavors to escape from the Capitalist system even though he is a producer. Therefore, such producer is a dreaming idler who has fled this system. If so, what knowledge does a flâneur produce? Knowledge ‘comes only in lightning flashes’ and ‘the text is the long roll of thunder that follows.’ The power that generates this type of knowledge is neither logical reasoning nor rational statement, but rather shock and the Erlebnis, or experience, of a catastrophe. In a nutshell, knowledge is a process which the fragile form of language is exposed. The thunder that weaves the roll of text is itself the poetic event.

However, there is no event in Portable Keeper. The event has already occurred, or alternatively has yet to happen. What the piece fundamentally exhibits is a man strolling around a construction site. This man appears to ramble at leisure, but unlike the flâneur he has no arcade to view. Already, the building has vanished and this solitary man is simply wandering about. In this respect, Portable Keeper becomes a parody of Baudelaire’s flâneur. Once a beneficiary of modernity, the flâneur is now destined to stroll around the ruins that have resulted from redevelopment projects undertaken under the banner of modernity.

The landscape of ruins imposes a nihilist attitude upon the flâneur. However, the ‘keeper’ grasped by this man loitering about the construction site serves as a device to counteract modern nihilism. The keeper, as the word literally indicates, is intended to be held in the hands with the aim of protecting something. What on earth is this man trying to protect? At this point, Lim projects an entirely different attitude toward what has disappeared. She is less intent on recording what has disappeared than on preserving what is currently in the midst of disappearing. Each and every scene captured in her pieces is something she aspires to safeguard. In other words, they are things that are made to return to language. This is evident in Rolling Stock (2003). The rapid change of scenes precisely corresponds to the rhythm of the music, as the scenes grasp for the disappearing images. This type of repetition will continue until an event occurs, and so will the music. In this context, the rhythm and melody of the music serve as a temporary residence.

4. Things that Become Possible only through Impossibility

The ruining of event is the element that renders the event’s entire formation impossible. It seems to indicate the relationship between the symbolic and the real as identified in the theory of Lacan. The real establishes an indivisible relationship with the symbolic, but is never embraced as a proper member of the symbolic. The real belongs to the realm of the unconscious, which in Laconic terms constitutes the whole of images and language the self borrows from others in order to complement the ‘place of privileged trauma’ known as sexuality.7 The unconscious constitutes an individual’s uniqueness. The self signifies the location of these peculiarities.

International Calling Frequency is an important project attempting at collectivizing this uniqueness of the agent. What is required in this task is the agent’s devotion, calling for the agent’s desire to lend him or herself to the international calling frequency. Badiou extracted his category of agent’s devotion as he analyzed Stephane Mallarmé(1842-1898)’s poem Un coup de dès jamais n’abolira le hasard. Badiou wrote, “On the basis that ‘a cast of dice never will abolish chance,’ one must not conclude in nihilism, in the uselessness of action8.” Here, nihilism occurs because one clings to a ‘cult of reality’ and fails to accept ‘its swarm of fictive relationships’ as they are. To put it another way, nihilism refers to the despair that results from a situation in which an agent intent on pursuing a subject does not acknowledge the fact that it is impossible to apprehend the subject. The obsession to represent the real eventually leads to nihilism, and, in contrast, the refusal to face it leads to one being swallowed by quasi-imaginative images that cast shadows deep down into the abyss of existence.

While Badiou captures behaviors other than nihilism through Mallarmé’s poem, Lim organizes a sequence of imaginative actions that characterizes the process of generating truths, known as poetry or art, through her work International Calling Frequency. Art reorganizes the world based on a foundation that precedes the traces of the real. This reorganization inevitably entails criticism regarding the existing world. Therefore, art does not halt at the simple level of techne, as art that settles for such level easily succumbs to nihilism. By reorganizing normative conditions, however, it is possible for art to conquer nihilism. In Jacques Ranciére(1940-)’s terms, this is to rearrange the distribution of the sensible. Badiou’s poetic virtue of Mallarmé is to set free the sensible — which has been divided by the community into a hierarchical order — on an aesthetic level and then to share it in a novel manner.

What is significant at this point is the act of reorganization. The process faces no choice but to go through the three stages of disintegration, abolition and then affirmation. Therefore, the act of art, which does not conclude in nihilism according to Badiou, does not denote an anti-aesthetic performance that remains at the phase of disintegrating the distribution of the sensible, but rather the production of the new that arises from the aesthetic premise. What indeed is the production of the new? It is an aesthetic dimension that incapacitates the sharing of all senses, as well as a precedent foundation that creates traces of an event—that is to say, a situation. Art is what fixes into text the debris of the event that has been left into ruins after the situation has expired.

Lim’s art intends to discover this situation within reality. It is her virtue to summon the situation that has disappeared, leaving nothing but the ruins. This is what the artist attempts to express in The Weight of Hands (2010). In varying degrees of temperature through an infrared camera, the work depicts hands which are both a product of evolution and a primary means of labor. What the colors convey can be seen as literally the weight of hands. Viewed from the outside, their invisible mass turns visible through temperature, demonstrating a conversion into sensorial realm.

What is necessary here is a transition from the negative to the positive. Lim implies that the action against the plunging into nihilism makes this transition possible. This action represents the devotion of the agent toward the truth of the event. This relentless pursuit of truth, which enables an event to have traces, is actually what Badiou refers to as the poetic spirit. Such truths are the absent causes that generate events. The task of poetry is, Badiou believes, to identify such truths. A complete text cannot be established from this perspective, because what poems ultimately intend to reproduce is the void of a situation that has already been subtracted. A void cannot be reproduced in text. As such, the text the artist exhibits by means of an infrared camera is actually the irreproducible. In this manner, Lim intends to explore ruins and present the points of truth using topology. As in the case of the symbolic, her works enter into existence as an artwork through such impossibility of establishment. If something like a map covered in signs and symbols is what Badiou regards as poetry, then Lim’s art is like a map in which colors and sound embodied in topological terms draw the contour lines.

From such perspective, Lim’s works appear to prompt subjectivism. They might leave an impression that the subject’s action comes before what the subject is attempting to capture. Such doubts can be raised since the subject does not reproduce the objective world, but rather demonstrates the accumulated subjective projections that relate to it. This is also the case with International Calling Frequency. One may think that this manner of performance, which denies any organization or medium, further promotes nihilism. The subject in each of Lim’s work, however, is always interlocked with objective, physical conditions that exist ‘over there.’ No matter how much the subject seeks out its object and argues the truth, there must be preconditions that make such actions understandable. Lim’s works constantly presuppose such conditions, which may explain the frequent appearance of reconstruction sites or sit-in strikes in her works.

Lim’s works always have a sense of concrete placeness. Of course, this placeness is not fixed, but has the tendency to be fluid. Lim’s interest lies on the fluid placeness, or the space of mobility. In order for the subject to establish a relationship with things, a cognitive framework should be in order. This is what Badiou regarded as the law of techne. The function in Techne is quite empirical. For example, techne signifies the method of matching images with their physical objects, through which normative universality in art is created.

Lim’s art combines the law of techne with the subject’s devotion. Even so, it does not indicate that Lim is trying to do so in order to strictly abide by this law. Rather, in the persistent manner of swaying the law of techne, she strives to incorporate the traces of truth into the text. Through this process, a new law of techne is created and the agent becomes ‘existent’ as both the one and the multiple. This very process is demonstrated in International Calling Frequency.

The moment one participates by tuning into the International Calling Frequency, the resulting existence can no longer be the same subject that was previously present. Participation itself becomes a performance. This performance imitates an event — an event that shakes the conditions of existence and thereby creates a new agent. Lim’s work becomes art only when it is able to birth a new agent. However, I must say that, ironically, this potential is always conditional on the impossibility of art. Reality demolishes the possibility of art. Lim is an artist who does not struggle against this condition, but accepts it as it is.

Herein lies the paradox that art is impossible, but for that very reason the pursuit of art becomes possible. Thus, sayability is a perpetual state of openness toward the thing itself. This state itself cannot be improved upon. The only thing one can do is pursue something within this state. In this respect, Minouk Lim’s art is the longstanding pursuit for possibility regarding what is impossible, performed in order to return things into language.

1. Agamben, Giorgio, “The Thing Itself,” Substance 53 (1987), p. 25

2. Benjamin, Walter, Reflections, Peter Demetz (trans.), (New York: Schocken, 1986), p. 325

3. Benjamin, Walter, “The Storyteller,” Selected Writings Volume 3: 1935-1938, Edmund Jephcott, Howard Eiland, et. al. (trans.), (Cambridge MA: Harvard UP, 2002), p. 149

4. Badiou, Alain, Being and Event, Oliver Feltham, (trans.), (London: Continuum, 2007), p. 192

5. Baudelaire, Charles, The Painter of Modern Life and Other Essays, Jonathan Mayne, (trans.), (London: Phaidon, 1995),

p. 9

6. Benjamin, Walter, The Arcades Project, Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin, (trans.), (London: Belknap, 1999), p. 417

7. Jeong hyun, Maeng, Libidology, (Seoul: Moonji Publishing, 2009), p. 7

8. Badiou, Alain, Being and Event, p. 198

Critic 2

Minouk Lim : Notes from the Journeys of the 25th Hour

Clara Kim

Senior Curator , Dept. Visual Art, Walker Art Center

Seoul is an urban landscape that changes before your eyes—a city of a kind of liquid architecture that gets destroyed as quickly as it gets built in a cycle of defamiliarization and discontinuity. Navigating the city, as anyone who has visited Seoul will know requires a relationship in which the past, present and future co-exist in simultaneous space. For instance, when you ask a cab driver to take you somewhere, addresses usually prove to be useless, but he will often ask you “oh, is it where Building X formerly was, which used to stand next to Building Y and where Building Z is currently under construction?” Seoul, like many cities in Asia that went through rapid industrialization, operates within the rhythm of a time-lapsed video. In this intricate and densely woven weave of roads, public transport systems, underground tunnels, and overhead highways, entire neighborhoods are eradicated and communities uprooted and displaced en masse for innumerable development and redevelopment projects, altering the city landscape like the unrecognizable face of a chronic plastic surgery patient constantly under helm of the knife. It is a patchwork that never quite comes together where histories, memories and everyday realities are held together by fragile seams.

“My sense of time does not follow the common sequence of past-present-future, but rather of past-future-present.”1

This is where Minouk Lim’s work begins. Over the past 15 years, Lim has developed a provocative body of work that critiques the social and political conditions of a contemporary society fueled by rampant growth and development. Interested in the silent, invisible, and peripheral aspects of industrialization—what the artist calls “the ghosts of modernization,” Lim responds to the loss of belonging and place. Her work unabashedly moves from declarative gestures of protest to symbolic rituals of mourning. Consciously working between the lines of aesthetics and politics, Lim’s works create spaces where dissent necessitates new ways of seeing and experiencing. Deeply influenced by the writings of Jacques Rancière(1940-) who defines ‘the political’ not by the relations of power or the achievement of a specific goal, but rather the active process of creating disruptions within consensus driven culture, Lim’s works operate as ‘dissensus,’ using Rancière’s term, or as interruptions to the political and boosterism rhetoric that pervades contemporary Seoul. For Lim, occupying a position of dissent demands a recalibration of our cognitive and sensorial processes, necessitating a different way of seeing and perceiving that recaptures collective memory and implants a conscience within the experience of lived reality.

“My ethical responsibility of art is an issue that draws attention from a number of artists. My stance is close to that of Jean Luc Godard(1930-)’s Le petit Soldat (1963) who said “Ethics is the aesthetics of the future.” I am interested in the sentimental judgment phenomenon, which has moved from ‘the good’ in truth and beauty to ‘beautiful.’ I believe that this is the same as looking into how our world holds disharmony together; it is because an action has to reorganize the sentiment about what cannot be seen, what cannot be heard and what cannot be spoken, as Jacques Rancière had claimed.”2

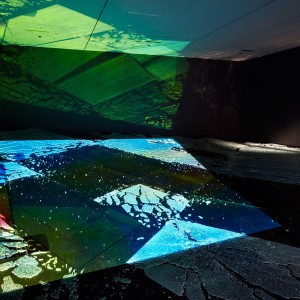

In recent years, Lim has acquired a distinct visual language that provocatively melds her interest in performance, video, and documentary. Commissioned by the BOM Festival, S.O.S.-Adoptive Dissensus (2009) takes the form of a three-channel video installation of a light and sound performance that originally took place on a cruise ship along the Han River. What Lim describes as a “performance documentary theater,” S.O.S. is a multi-layered work that is an immersive sensorial experience with searchlights scanning the nightscape of Seoul as an audience on the tourist cruise boat (or the audience of the video installation) are taken on a journey of the unknown to the 25th hour. The long time captain of the cruise ship becomes the narrator of this journey in which lost histories and memories wiped out by urban development initiatives like the Seoul city government’s ‘Miracle of the Han River’ project are recounted. Using real time, two-way radio, the audience come into contact with three performative vignettes that happen on the banks of the river: a group of student protestors in arms, two lovers who recount their emotional ties to Nodeul Island, and a former political prisoner of conscience recounting his personal story of struggle. Together, they trace a narrative of the individual lives and personal memories, from different times, places and social contexts collapsed into the space of one work, in an attempt to humanize the cost of modernization.

“My work throws the question on the relationship of memory faded by speed, resistance from it and the relationship between human beings and nature inside the city. This rapidly changing environment erases our memories and we have to prepare ourselves to let go of the memories without making them. The dizzy process of ‘globalization’ seems as though ‘we have already seen it’ and ‘we have already lost it,’ while wondering about the restless time.”3

Reinventing documentary as a form of direct engagement, Lim upholds the importance of the audience in her work as witnesses to the dissenting voices of history. For the artist, seeing is the act of sensing and touching—a poetic achieved by the embodiment of real time and space. If S.O.S. used sound and searchlights to capture lost spaces, The Weight of Hands (2010) uses the infrared camera, typically deployed for military surveillance purposes, as a literal and metaphoric tool to penetrate through a cordoned off construction zone. The work operates as a funerary ritual of sorts, in which a group of sojourners on a tour bus, attempt to break into a restricted space of development. The haunting video is punctuated by a woman passenger on the bus who is raised up and passed from person to person, while singing a ballad of loss, hopelessness and alienation, while the infrared camera footage records temperature and heat as a series of brightly colored abstract patterns in different hues and intensity. They are the literal and metaphoric stand-ins for lost bodies in space, in a context where physical spaces are restricted or no longer available, the work considers us to use other sensory devices—touch, temperature and heat as a way to see and experience our reality. The use of infrared camera would figure again in Lim’s subsequent work, becoming the technical device that carries and furthers her ideas of perceiving beyond physical attributes, of charting the traces of human existence.

“Today, under the changes caused by globalization, places are counted only as space; individuals are merely resources for networking. Nietzsche was said to have wept as he embraced a downtrodden horse, but I want to weep, embracing places. Nevertheless, I also want to fight against the sense of powerlessness caused by melancholy, whether is it the feeling that overwhelmed Nietzsche, or any other kind. So I am inventing rituals for, and keeping records of, moments of separation.”4

Lim’s FireCliff performances, now three in the series, extend her interest in the relationship of the body in the city, of the witness to phenomenon, of placeness and history. The first was performed at La Tabacalera in Spain in 2010—a cultural and community center in a former tobacco factory building in Madrid. For the performance work, Lim interviewed former female workers of the tobacco factory, relaying their stories, their working conditions and eventual lay off and performed their texts in what she calls site-specific installation and sound performance with hip hop music and other sounds and light effects. For Lim, the work is an effort to rekindle the history of place, to uncover the stories that are buried deep in the ground or embedded in the walls of the building—forgotten as new lives pass it by. The FireCliff performances are rituals of sorts that summon the past, present and future in precarious ways. FireCliff 2_Seoul (2011) was performed on the occasion of the 2011 BOM Festival in Seoul. Interested in the relationship between memory and testimony, Lim realized the performance in a more classical theatrical configuration, with audience and a stage set up in a building formerly used as a security intelligence complex. The performance featured two individuals: Hyeshin Jeong, a psychiatrist and Taeryong Kim, a long time political prisoner (who Lim had met while working at the Truth Foundation) and the space of the theater was turned into a documentary space—in which the drama of one’s own life, lived and performed by that person, unfolds to an audience. FireCliff 3 (2012) was performed on the occasion of Lim’s exhibition at the Walker Art Center in 2012 and went step further in the integration of choreography, dance and sculpture. As a continuation of Lim’s interest in the space of theater, performance and movement as invoking the active participation of its participants, Lim worked with a choreographer in creating a movement based performance around an imagined apocalyptic landscape. For the first time, she incorporated sculptures in her performance—a newly commissioned series of totemic forms (which appeared first in her video Portable Keeper (2009)) and wearable sculptures. Inspired by André Cadere(1934-1978)’s wooden bars, Krzystof Wodiczko(1943-)’s homeless shelters and Hélio Oiticica(1937-1980)’s parangoles as well as the recent nuclear disaster in Fukushima, Lim created these biomorphic forms from thermofoam and other scavenged organic and synthetic materials as protective shields and devices for the body within an apocalyptic landscape. For Lim, they represent the desire to defend the collective consciousness within a terrain of shifting forces and uncontrollable ambitions while advocating for a deeply humanistic position of empathy, sentiment and resistance.

“We are all born into a theatre. I even consider the womb to be a stage – a liquid theatre. After we’re born, we build a concrete theatre. Half of life is acting in a fiction, and we all consider our roles in reality. I’m not satisfied with the common definition of ‘role.’ I always hear these questions: What is the artists role in society? The father’s role? Mother’s role? Professor’s role? These roles have been more and more reinforced. I would like to rediscover the notion of roles in order to question how much is reality and how much is illusion. So, I’m not thinking about blurring a borderline, but rather a coexistence of fact and fiction. In theatre we talk about an actor as an instrumentalized body, speaking someone else’s script, but I am using the term in its more active definition. As an actor, we have potential to decide our own role.”5

Lim’ most recent work Liquid Theater (2012) which premiered at the La Triennale Paris is a video-based installation that consists of totemic sculptures (aka Portable Keepers) and a video. The work takes video footage of the recent death and funerary processions of Kim Jong-Il(1942-2011) as well as archival footage of Park Chung Hee(1917-1979)’s—the two eerily undistinguishable, as well as incorporates Lim’s thinking about Fukushima and the rise of suicides in South Korea. Images of public mourning become stand-ins for private mourning—for the loss of lives that are not commemorated or counted, whose deaths also has the right to be mourned. For Lim, the mourning images, though rooted in fascist ideology, have a primitive quality or rather represent a primitiveness in our humanity. By bringing this footage together with explosions, Liquid Theater presents a possibility in reversing the repercussions of tragedy, in this case how the death of Kim Jong Il might present a beginning rather than an end. To that end, Lim imagines a tropical Korea represented by footage of her daughter on the Caribbean island of Guadeloupe, so seemingly distant from the specificities of Kim Jong-Il and Park Chung-Hee, but in fact rooted through the biography of her child. She envisions a tropical Korea, a mise en scène of a tropical extreme that creates a new imagination through the destruction of old ones (its political ideologies and capitalist ambitions) and in doing so aims to dispel the false rhetoric of progress by returning to a primitive state where things might become possible again.

“I would like to track the cultural entangling from the modernization period, something primitive and original, but neither unique or common. I would like to tell a story beyond what we see, hear, know and believe to know. It seems that there is a place where the original spirit of the media resides. It is my belief that the nature of art should be set against the hegemony covering a wide range of genres, and the politics should also be the same.”6