Bek Hyunjin

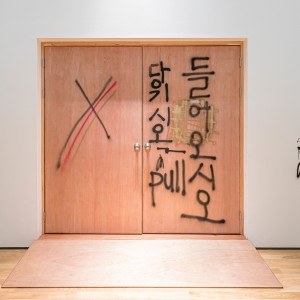

Bek’s new work, UnemploymentBankruptcyDivorceDebtSuicide Rest Stop, turns the exhibition venue into a refuge, a resting area, and a place for meditation, as well as a multipurpose space. These are pathological phenomena that occur like dominoes throughout Korean society, and all of these horrible, sad, and lonesome conditions are my stories and our stories at the same time. A virtual scenario, or “poem,” about a man is placed at this “Seoul-style rest stop”. While wearing many hats during this project, the artist plays the role of an “enforcer” who has organized the place itself and its user in an almost back and forth way. He allows viewers to become naturally involved in the scenes so that they can experience and complete a play on their own.

Interview

CV

2017 In the Neighborhood, Perigee Gallery, Seoul, Korea *performance

2016 Field, Bird, Dog and Talent, PKM gallery, Seoul, Korea *performance

2013 Hyunjin Bek, Choi & Lager Gallery, Cologne, Germany

2012 Hyunjin Bek, 43 Inverness Street Gallery, London, UK *performance

2012 Paintings Next Door, ggooll & ggoollpool, Seoul, Korea *performance

2011 Thirteen Pieces + bonus, Doosan Gallery, Seoul, Korea

2010 The End: The Linear Version, PKM Gallery, Seoul, Korea

2008 Vagrant N’ Substance, Arario Gallery, Seoul, Korea *performance

2007 Adjective Look, Viafarini, Milan, Italy *performance

<Selected Group Exhibitions>

2017 UnemploymentBankruptDivorceDetSuicide Rest Stop, Korea Artist Prize 2017, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea *performance

2016 MMCA Residency Changdong Report 2016, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art Residency Changdong, Seoul, Korea *performance

2016 Please Return to Busan Port, Vestfossen Kunstlaboratorium, Vestfossen, Norway

2015 Have a Good Day, Mr.Kim!, Michael Horbach Foundation, Cologne, Germany

2015 Tracing Shadows, PLATEAU, Samsung Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea *performance

2014 82-33-44, Choi & Lager Project, Paris, France

2010 Plastic Garden – Korean Contemporary Art 2010, Minsheng Art Museum, Shanghai, China

2007 Elastic Taboos, Kunsthalle Wien, Vienna, Austria *performance

2006 Alllooksame? / Tuttuguale? Art from China, Japan and Korea, Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, Turin, Italy

2006 EgoMANIA, Galleria Civica, Modena, Italy

2002 Reality Bites 02, Alternative Space Loop, Seoul, Korea

2001 Active Wire, Art Sonje Center, Seoul, Korea

<Collection>

Seoul Museum of Art, Korea

<Residency>

2016 National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Artists of Residency Changdong, Seoul, Korea

Critic 1

Ho Kyoung-yun (Art Journalist)

I first knew Bek Hyunjin as a musician, when I became a fan of his band, Uhuhboo Project. It wasn’t until 2004 that I saw one of his paintings, and then in 2008, I attended his solo exhibition. Bek used to introduce himself as a young man creating literature, music, and visual art, but he now considers an “omnidirectional artist.” I also used to think that he was working in various fields and genres, but I have recently begun to see all of his different activities as one. Admittedly, I do not know the precise definition of “omnidirectional art.” But I can say with certainty that, although Bek’s different activities might belong to different fields, they are not unrelated, and he is not just playing around independently. After all, all of his work seems to result from an outpouring of the fundamental human desire to synthesize playfulness and “creation.”

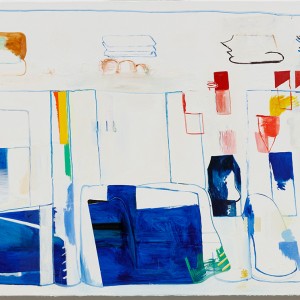

In 2016, Bek held a solo exhibition entitled Field, Bird, Dog and Talent, which featured twenty-five new paintings and drawings, as well as a sound performance called Face to Wall. Every day during the month-long duration of the exhibition, he came to the exhibition gallery and gave an impromptu performance while facing the wall. This exhibition exemplified the unique sensation that only Bek Hyunjin can provide, as an artist who sings as well as paints. Interestingly, even if the visitors missed Bek’s daily performance, they probably felt like they were attending a performance as soon as they entered the gallery.

This is because one of the consistent elements of Bek Hyunjin’s art is physicality, or more simply, the body. Of course, his musical and acting performances are naturally based on the “body,” but his paintings also evince the body, by drawing our attention to the movements of the brush over the canvas. Moreover, the way that he belts out sound from deep in his body is more akin to wailing or howling, rather than singing. Describing Bek’s works, art critic Lee Sunyoung referenced Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari: “[Bek’s works] demonstrate the changeability and fluidity of the un-hierarchized body. According to A Thousand Plateaus, the body is no more than an aggregation of valves, sluices, bowls or communicating tubes….The explosion of the hierarchized organism is not the dead body, but the even more alive body filled with polymerism, namely, ‘body with no organs.’”

On the other hand, one aspect of Bek’s art that seems to be at odds with physicality are the unusual titles of his works: Modern Talk Coming from an Asian who Has Experienced Strange Stones and Trees After Neurology and Particle Physics; Vectors or Pixels or Whatsoever; A Young Man with a Face Reminiscent of Someone from the Movies, by Nature Positive, but like an Old Man Living Alone, Very Poor and Forlorn. These highly literary expressions reflect the unorganized landscape of a desultory mind.

Notably, a drawing that appears on the first page of his art book Organism, Mechanism, Blurism shows three words—“text,” “painting,” and “music”—intertwined within a triangle. These eclectic stories and ramblings, which are continuously generated and entangled within his mind, form the foundation of Bek’s art. The resulting works, which are unorganized yet loosely parallel, present the squirming potential and possibility for a new type of art. Thus, I am recommending Bek Hyunjin for the Korea Artist Prize, based on my belief that the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul must also propose the new art of the near future. I am very curious to see what unpredictable outcome Bek could generate within the competitive context of this award.

Critic 2

Darkness Is Your Candle

Jee Young Maeng (Curator, DOOSAN Gallery)

“We leave this world on our own without having knocked on every door.”

from Suicide by Reiner Kunze

1. Beginning and Ending Are the Same

Morning. An unexpected text message. My friend’s father has died. Someone else’s death affirms the existence of time, which pushes me towards death. And it makes me think again about the time of other people. The weight of unfathomable death. The futility of words. The fear of imminent absence. As death slowly approaches through illness, the dying person, along with friends and family, gradually goes to meet it. In the same way, preceding death and feeling its portent, a person committing suicide meets death in a single stroke.

Pressed by the weight of society, city, and family, we seek respite in the forest of oblivion. To get there, we just take a drink, while talking nonsense and swearing at the stifling reality that awaits us tomorrow. The world is no longer a simple space speckled with naivety, kindness, fear, and hope, as it seemed in childhood. Instead, it is filled with incomprehensible things, which are outrageously complicated, absurd, desperate, frustrating, and yet hopeful. But in fact, the world of my youth is the same as the world of my adulthood. Still, when I was a child, I followed a narrow path created by ignorance, forgetfulness, and avoidance. How far down does the damaged surface extend, with its scars that have been constantly covered, erased, and painted over by memories and wounds?

The tang of embracing and tending those wounds, while still burrowing deeper out of sight, brings us comfort, stirring our hearts while tangling our thoughts, before erasing them altogether. We are silenced by the desperate pain, which leaves us unable to cope with the waxing sadness, prohibiting outward expressions. Finally, the moment comes when we can exhale, a little sigh. But the moment only comes after we have distanced ourselves from the sadness.

2. In Korea, Somewhere, or Here

I think about the densely overcrowded landscape of Seoul, where everything is connected, but only by the most tenuous links. The constant cycle of tearing down, digging up, hardening, covering, building up, wearing down. Patches of broken pavement, probably laid decades ago, are poorly mended with cement. Drops of paint splattered on the road while painting the lane markers. Tiny houses and flats wedged together, separated only by narrow alleys that are heaped with piles of trash awaiting the garbage truck. Some lines wriggle out from the grimy surface, while some colors absorb into one another, becoming invisible. This enshrouded landscape, and the people who live there.

We are all born and raised in different environments, but none of us can escape the essential components of our homeland and our era. Whether we agree or disagree with them, those minute components are embedded inside us, often without our awareness, becoming part of us. We must occasionally confront the weight, complexity, unfairness, and injustice of reality, for incidents both monumental and trivial. In doing so, we feel constricted yet refreshed, bothered yet relieved. Sometimes we meet with others to discuss the meaning of life, all the while thinking about its meaninglessness. Some get angry about the inviolable social system, drinking themselves into oblivion and shouting at the sky. Others go to the demonstration at the town square and insinuate themselves into the crowd, as if they have been there from the beginning.

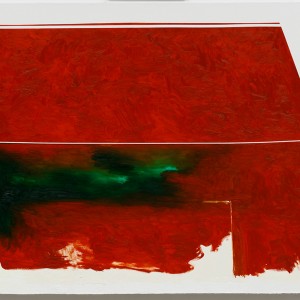

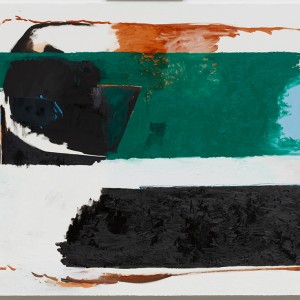

Quadrilateral blocks of pavement, quadrilateral tiles, quadrilateral buildings, quadrilateral canvasses…quadrilateral rooms…and then, paintings again. Coarse and shattered worlds are painted inside a canvas, here and there. The paintings are somehow both rough and smooth, indifferent but elaborate. Sometimes, Bek Hyunjin refines sharp edges until they become round. Through this process of painting, re-painting, covering up, and erasing, a window to the world eventually emerges, disappears, and re-emerges within a quadrilateral canvas.

Likewise, a wide range of emotions can appear and disappear in a single day, or sometimes even within a few minutes: a constant ebb and flow of joy and pleasure, emptiness and despair, pain and sorrow, and anguish soliciting renunciation. Just as each part of life is the same as the whole, a painting is both a part and a whole. By reminding us that nothing is intact on the surface, Bek’s paintings casually offer some consolation.

We are so far above the surface of the water.

3. Darkness Is Your Candle

Morning returns, and we are once again compelled to throw ourselves to the crowd. Although this pattern endlessly repeats, I can never get used to it, perhaps because I’m not yet desensitized to the world. I should be numb to it, but I still see the garbage bags of assorted sizes, leaning on one another for support. The landscape has slightly changed since yesterday. In front of the supermarket at the end of the alley, the gaps in the pavement get a little wider every day, gradually exposing the earth beneath and allowing various life-forms to emerge. Passing the alley and entering the boulevard, I see the utility pole that I noticed last night, when it seemed to resonate with a certain grandeur, like one of the town elders. Now, however, I see that the dull grey surface of the pole is covered with multicolored leaflets for loan companies, perhaps giving me a sign of how my day will go.

This makes me remember that time I got caught in a downpour after school, without an umbrella. As I got soaked, I felt some concern for my mother, who would now have a heavy load of laundry, since my school uniform would have to be washed. But at the same time, in those brief moments of dashing through the rain, I felt liberated. This is what I remembered as I looked at the grey utility pole, and the grey sky that could open up with rain at any moment. I cannot remember the details of that day. Was it spring or fall? I don’t remember feeling cold, so perhaps it was a summer day. Even though this happened decades ago, I feel it more clearly than what happened yesterday.

It’s not everyday that feelings from the distant past overlap with the present during my short commute to work, which takes only about an hour. Or maybe each day is nothing but the overlapping of such moments from our history. If I take the subway to work, I have to make a couple transfers, which I don’t like. So I often prefer to take the bus, which delivers me direct, but requires me to walk some distance to the bus stop. Also, I feel uncomfortable in the bright white light of the fluorescent lamps in the subway, which seems to penetrate through everyone and everything inside the car. I should be used to this by now, but I’m still uncomfortable. During rush hour, I can’t use any device to help me ignore the lighting. Packed into that dense crowd of people, I feel that it’s a luxury to have something to contemplate, but maybe that’s just my excuse. I think about Buddhist teachings, which tell us that the differentiations between myself and others are meaningless. But even if I accept that we are all the same, isn’t it futile if someone else perceives us to be different? And is it even possible for me to accept this lesson? Arriving at work, I sit at my desk, turn on my computer, and spend most of the day staring at the monitor. There is so much work stored inside this machine, that I can’t take my eyes off of it. The computer seems to have a certain power that switches off my other thoughts. Fixing my eyes on this small space, I disappear for hours at a time, only escaping by turning the monitor off. After years and decades of doing this, I can also disappear when I’m not at the computer. Of course, we will all eventually disappear with death, but I still feel sorry for myself, because I keep losing myself without awareness.

Even though I try to avoid asking others for favors, things don’t always go according to plan. I was doing well, I didn’t have any big dreams; I just wanted to work hard to do my part, without harming anyone. But the weight pressing me from every side never lessens. Rather, it gets heavier and heavier, like soaked cotton.

My heart sinks after a phone call that I wasn’t ready for. I once thought we loved each other, and I believed that the relationship would last, just like we promised. But suddenly, the voice on the phone is unfamiliar. Since then, even the sound of the phone ringing frightens me. The careless words of a colleague sting my heart. The words are not directed at me, so why am I so affected? I trudge down the stairs, rather than taking the elevator. Even though the elevator takes only a few seconds, I don’t feel like submitting to the gaze of others. I don’t want anyone to notice my flow of emotions. I’m desperate to give myself rest, to free myself from everything that I’ve been clinging onto. I go outside. Although the space around me changes, I stay the same. In Korea.

Darkness is upon us again.

4. I. Paint. Like That.

There is always a struggle between the self that I am and the self that I want to be.

No matter how hard I have searched, no part of me is left unscathed.

It feels unnatural when someone tries to align the angles by force. So the brushstrokes seem scribbled and spontaneous here and there, wherever he wanted it to look more natural.

Distorted,

Relaxed,

Dull,

Disheveled,

Scattered surprising acts,

The uncertainty of faking certainty,

Stillness among disturbances,

Power reminiscent of something, but preventing recollection,

Balanced brushstrokes towards imbalance.

However, the brushstrokes break the balance inside themselves. Shapes. And colors.

Sudden protrusions from the canvas send our eyes on a detour in a different direction.

Numerous hesitations,

Repetition of painting and erasing.

5. Breakroom

Fried chicken joints, bankruptcy, divorce, suicide.

I found these words written on a canvas or piece of paper while visiting Bek Hyunjin’s studio in Yeonnam-dong in 2015, and they hovered in the air around us, like broken headlines from the news. It took some time before they landed on his paintings, and until I recognized them not as fragments, but as a connected loop.

For whatever reason, the images make me feel hesitant, but I cannot turn away from them. They stir a mix of feelings: confusion and relief, embarrassment and excitement. At the time, I couldn’t put these feelings and sensations into words. They are still piled inside me, haunting my mind. I hope that someday I’ll be able to express them in more precise language. In the meantime, I let them sit inside me, where they might spawn a word or an image at any moment.

Looking at paintings,

Looking at them blankly for a long time,

I realized and became frustrated by the fact that there was not much that I could do to deliver the stories that Bek’s paintings told me.

However, while I was listening to the stories told by these paintings, it was time for me to stop and time for me to move.

These paintings were my “breakroom.”

In the eight paintings of this exhibition, Bek Hyunjin addresses the life and landscape of someone living here and now in Korean society. The person is an individual but a non-individual, living a life that is neither comedy nor tragedy. Looking at Bek’s changing paintings, I truly felt the immense courage that they required; indeed, they must have been an almost impossible challenge. At first glance, the paintings seem to consist of a repetition of trivial and habitual forms. But the brushstrokes unexpectedly emerge to break the pattern of habitual behaviors, incessantly transgressing the mannerism of the viewers. The colors, the varying applications of the colors, and the strokes within the color fields signal subtle emotional changes.

Perhaps the familiar landscape of Seoul that Bek depicts is gradually changing into something exceptional. As younger generations grow up in and grow accustomed to precisely arranged apartment complexes, the world is becoming more sleek and polished. At the same time, the will and ability to resist that sleekness diminishes. When the people of this country had almost nothing, we busied ourselves by thickly covering the surface. Then, while we were polishing the hastily made surface, its roughness came to be regarded negatively, so we strived to make it sleek and glossy. So what comes next after the sleekness? Should we just tear it all down and start over again?

By instinctively creating these eight paintings, Bek Hyunjin may have been thinking sequentially about what comes after sleekness. He never tries to hide the reality and the landscape that the people of our society face. By continuously applying and erasing brushstrokes, Bek leaves traces of the scars and ruggedness of the present. He does not consider the landscape to be uncomfortable or embarrassing, and he does not think that it must be changed. Instead, he embraces and agrees with the landscape, and he feels sorry for it. As such, he intends to show it as it is.

Bek and I share the fear that, after everything has become sleek, no one will look back and remember the true landscape, society, or people of “now.” If these things are not imprinted on us, they will be forgotten. Thus, Bek uses his paintings to imprint them on the viewer. And through his arduous painting process, he captures the version of history that has been imprinted on his body. Likewise, I look at his paintings again and again, trying to imprint the history of his paintings on myself, so that I will not forget.

6. In Search of a Perfect Quadrangle

In front of a painting, I can truly be myself, even when surrounded by obstacles interfering with my stream of consciousness. Listening to the whispers from the images, I can see the scattered pieces of myself. The world incessantly opens and closes through one person. We all have moments of passion, when our feelings and thoughts pour out in a torrent. But in those moments, for whatever reasons, we fail to consider the listener, thus preventing true communication.

Now, having some space for the other party, we attempt conversation. This conversation is ongoing, although it might not be open to everyone. Taking a moment to look at a painting might initiate a conversation. Taking some time to look at the painting will take you to unexpected places.

I sense the signal that indicates both the beginning and the temporary end of the conversation. At first, I was so absorbed in the conversation that I couldn’t turn away from the painting, but now it gently pushes me away.

Everything that has to be said remains unspoken.

But for a long time (or at least for a little while), I might have silence.

I’ve been looking around for the quadrilateral canvas that I can depend on.

What did I see?

Traces of brushes on the surface might be a certain symptom.

Those traces might reveal the bare but hidden face of the current society, through the history of one person.

Nonetheless, the traces are both straightforward and camouflaged, so that they do not disclose anything directly. We must also question whether such disclosure is necessary. The unsophisticated and non-meticulous thinking of a human cannot suddenly expose the vulnerability of such a bare face. Instead, at the very moment when we recognize the vulnerability, it is erased and concealed, so that the whole thing begins again. The painter transcribes the history that is imprinted on his body into a painting. The brushstrokes take so much time, but whatever they reveal is probably not enough to inspire the blind allegiance of the viewer. So why does he persist in making the brushstrokes? Why does he insist on penetrating deep into the gaps of this society, filled with countless layers of absurdity, pain, sorrow, and joy? What does he see and feel, and what does he want to see? Through brushstrokes, the painter silently regards and responds to the incessant changes and the eternal monotony. In this way, the painter narrows the distance between himself and the world.