Inhwan Oh

Based on his personal experiences, Oh translates or dismantles the cultural code formed in the connective context of relationship between individual identity and group within the patriarchal society. With this, he also proceeds on with concrete and practical works pertinent to the daily experiences implanted with keywords of the contemporary art including, difference, variety, communication and more.

Interview

CV

2014

<Looking Out for Blind Spots>, Space WILLING N DEALING, Gallery Factory, Seoul, Korea

2012

<Street Writing Project>, Sindoh Art Space, Seoul, Korea

2009

<TRAnS>, Art Sonje Center, Seoul, Korea

2002

<Smoldering Relations>, Mills College Art Museum in Oakland, US

<Major Group Exhibitions>

2014

<A Room of His Own: Masculinities in Korea and the Middle East>, Art Sonje Center, Seoul, Korea

<Spectrum-Spectrum>, Plateau, Seoul, Korea

<SPACE CRAFT : Interface and Potential Space>, Seoul Olympic Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

2012

<Dislocation>, Daegu Art Museum, Daegu, Korea

<Playground>, Arko Art Center, Seoul, Korea

Critic 1

Others and Me: On the Impossibility of Relations and Communications

Woo Jung-Ah (Professor, POSTECH Humanities and Social Sciences Dept.)

For the exhibition at PLATEAU in the summer of 2014, Inhwan Oh produced the project Guard and I, a work that unveils the tension between individual identity and social norms, critically examines the institutional order of a museum, and exemplifies Oh’s persistent attempts to communicate with others on an intimate level, even if the relationship is temporary.

Guards are present in every museum, but they are very inconspicuous; in fact, even though our eyes see them, they are invisible. While museum visitors are entirely focused on the exhibited works, the guards’ duty is to screen the visitors who are looking at the works. Through the guard, the visitors change from “seeing the subjects” to the “seen objects,” or more precisely, from the “watcher” to the “watched.”

Inhwan Oh, who has entered many museums as a visitor, considers the guard to be one axis of the social power structure that observes individuals, indirectly recalling Foucault. In particular, the guards at Plateau Gallery are always young men, sharply dressed in fine suits, equipped with earpieces, and armed with a very polite yet stern attitude. Accordingly, under their “surveillance,” the visitors implicitly conform to the order enforced by the museum.

However, when someone like Inhwan Oh, whose works are displayed in the gallery, enters the space, the power structure is inverted. There are three basic levels of labor taking place in a museum: the labor of the artists, which is elevated to a nearly divine level in the name of “creation”; the labor of the curators, which is contained within the specialized scholarly domain; and the labor of the guards and custodians, which is regarded as simple manual labor with no added value. Hence, as an artist, Inhwan Oh occupies the highest position, not only in the museum, but apparently on the ladder of class and labor that pervades the entire society.

In addressing this complicated hierarchy, Inhwan Oh aims to change the entire system by exposing the layers of cultural meaning that exist between his role (simultaneously a viewer and the artist) and that of the guards. While producing the work, Oh devised a project that he could do together with the guards of Plateau Gallery, and he thus proposed a very ordinary and simple “meeting” for that purpose.

In seeking to contextualize this work, we must first acknowledge the tradition of critiquing the institution of the museum, a fundamental concern of the neo-avant-garde since the 1960s. The representative figure is the American performance artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles (b. 1939), who cleaned the museum as performance, calling it “Maintenance Art.” But while Ukeles primarily worked independently, Inhwan Oh required the active and voluntary participation of the actual guards. Given that he interacted with the guards and attempted to form some relationship with them, his work may also be connected to “Relational Aesthetics” or “participatory art,” in a more contemporary sense.

It has already been some time since relation, participation, and communication became the most representative keywords for defining the working methods of contemporary art. Today, these words sound rather conventional and vapid, but they acquire concrete and substantial significance in Oh’s works, because they do not invoke any grand social discourses, nor do they serve as simple abstract slogans or overly optimistic prospects.

What can guards and an artist do together in a museum? But before they can do anything, shouldn’t they get to know each other a little bit first? With this in mind, Inhwan Oh notified the guards of Plateau Gallery of his intentions and the goal of his work, and one guard finally agreed volunteered to participate. Oh and the guard agreed to meet ten times; after each meeting, the guard could decide whether or not to continue the meetings. For their first meeting, they had tea together, the standard ritual for any two people who are thinking of building some kind of relationship. In their second meeting, they became more comfortable talking and sharing their stories with one another, and in their third meeting, Oh invited the guard to his studio and showed his works.

The original plan was that, after the ten meetings, Oh and the guard would dance together at the museum. If the plan had been realized, it would have been a legendary event that would resonate in the history of Korean contemporary art: an artist and a security guard met many times outside the museum, came to intimately understand each other, and finally danced together in the museum. Though perhaps this storybook ending would have felt a little mundane in the environment of contemporary art, where, with the aid of “aesthetics,” themes of relation, participation, and communication have automatically become the object of superficial sentimentality and admiration, regardless of the actual contents.

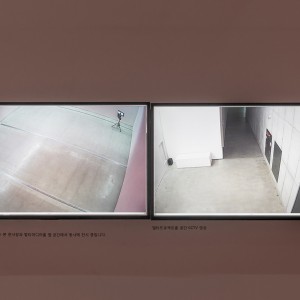

In Oh’s work, however, the dance was not meant to be. After the third meeting, the guard declined to continue, bringing an end to the project. Inhwan Oh was left to waltz alone at the museum, spending the two months before the event diligently learning the dance with a private instructor. He danced in front of CCTV cameras, which stand in when guards are not present. As such, Inhwan Oh as an artist became the one who is “surveilled” in a museum, but at the same time, the tool of surveillance became the work itself. Through this process, the boundary between surveillance and appreciation disintegrated.

In fact, the true achievement of this work lies in the failure and incompletion of the process. Like Lee’s previous works (Where Man Meets Man, Things of Friendship, Lost and Found, and Meeting Time), Guard and I exemplifies the fact that questions of identity—namely, the tension from “differences” between me and others and the conflicts that individuals face because of social norms—can never be reduced to homosexuality. Thus, in trying to determine the true reasons why the project was interrupted, viewers are left with many layers of speculations and inferences.

In the final work, each meeting between Lee and the guard was to be documented with a booth. But since the final seven meetings were not realized, the work includes seven empty booths. It is never easy for a person to participate in actions that violate the codes of one’s occupation and social status. Even with good intentions and just cause, “relation” cannot be formed in a short time. Likewise, perfect “communication” cannot be achieved through the steps of a waltz that one has learned through rote practice over only a few months. As such, the seven empty booths represent a profound question about art’s capacity for social criticism. I hope that the exhibition of the Korea Artist Prize 2015 offers Inhwan Oh the opportunity to somehow fill in those seven booths. But even if they remain empty, I am certain that the artist will fill the space with more questions and thoughts.

Critic 2

Inhwan Oh: When Attitude becomes Structure

Jung Ah Woo (Professor of Humanities and Social Sciences Dept., POSTECH)

1. The structure of nomination

When I called her name,

She came to me and became a flower.

- The Flower by Chun-su Kim

Inhwan Oh presented his work, Name Project: Looking for You at the Busan Biennale in 2006. He wrote down 20 names on a wall of the exhibition space and looked for those who shared the names by calling out each one regularly over an announcement.1) If someone came after hearing the announcement, he or she would listen to the artist’s description of the project, have his or her picture taken, and sign the bottom of the photograph. The 20 names the artist had chosen were among ‘the most common names’ in Korea. I had heard eight names of people I personally knew very well, eleven if you count different people with the same name. (One of them had recently changed the name as the person disliked how common it was.) Even so, how high was the possibility that some visitor at the biennale, with one of those twenty names, was there at the exact time of the announcement to hear it?

To take a concrete example, even if someone named Minjung Kim listened to the announcement that called her name, it is perhaps not easy to answer the call with conviction that ‘the name being called now is really my name’ as she probably experienced similar confusion before since many have the same name as her. At the Busan Biennale however, the individual named Minjung Kim came to the artist after listening to the announcement. The name ‘김민정’ (Minjung Kim) written in dull print letters on the wall looked completely different from the signature of ‘珉貞’ (Minjung) written in cursive. Afterwards, her name was not called anymore as this common name became concretized as the one and only individual, ‘Minjung Kim’.

In the poem, The Flower, poet Chun-su Kim sang about how amazing the ontological power of “calling one’s name” could be.2) Before I called her name, she was “nothing more than a gesture” but when I called her, she came to me and “became a flower.” As such, an indefinite, uncertain being could become a meaningful being only through ‘my’ nomination. And yet, even ‘I’ am not a complete subject. Only if someone calls my name that “suits my color and fragrance,” I, too, can become or long to become “the flower.” In this way the poet scribed, “You for me, and I for you long to become an unforgettable glance”. When the poem was published, ‘glance’ was initially written as ‘meaning,’ but the poet revised it afterwards. An insignificant being shall be called by its name, i.e. ‘nomination’ to secure a place in the world. In order for ‘nomination’ to occur, the subject and the object must exist. The subject defines the other’s ‘color and fragrance’ and their identity, imparting an appropriate meaning to the other, and forms a relationship by calling its intrinsic name. The relationship is not concluded unilaterally but moves in a bilateral cycle.

The principle of this bilateral subjective nomination penetrates the works of Inhwan Oh. It is the artist who calls upon ‘Minjung Kim’ at the exhibition space but the person who decides whether or not to answer the call or join the project is Minjung Kim. Only with her participation, the project can be completed and only through the project, Oh can exist as an artist. Oh’s work is usually completed by the existence and will of the others in the exhibition space. Accordingly, the completion or incompletion of his work depends on an external environment and condition. Even if his work is completed in any way, it is nothing but temporary and his status as an artist is always unstable and erratic. Since he decided to work in the Republic of Korea as a homosexual artist, his life is bound to be insecure and precarious at times. He believes that his work has to reflect his life as a whole3) which is why the structure of his work is also unstable and risky. His attitude becomes the structure of his work.4)

The structure refers to the method of producing meaning from the action of a work. This category is distinguishable from any formal style or referential imagery. Oh’s works do not reveal aesthetic qualities, iconic representation, or textural narrative. Although his work is at times defined as ‘conceptual art’ that harnesses language and text, his idioms are neither for tautological analysis of the definition of art, like those of Joseph Kosuth’s works nor for a self-referential objective like the texts of Lawrence Weiner. If Oh’s art is conceptual, than it may be closer to the meaning in contrast to the ‘visual’ or ‘formal’ and it may correspond to the institutional critique of the conceptual art, in the historical context. However, unlike Hans Haacke’s work, however, Oh’s works are not restricted to debunking the political limitation of art museums.5)

Oh’s art is conceptual in that it reveals that ‘meaning’ is not a matter of ‘taste’ but the issues of the ‘power.’ He is careful to not come off as a doctrinaire artist who makes forays into offering the public “’politically correct’ art or an authoritative being who considers himself to be a representative of the minority defiant of the majority. He does not offend by displaying overpowering spectacles in the art museum in a bid to assert his great cause and also cautions himself against sentimentalism as he becomes excessively immersed in emotion, delaying any rational judgment. He leads viewers to engage whereas the viewers have to act upon their own will. The participants’ identities undergo a temporary process of transformation within this. They experience cracks in their self-awareness, distrust in their ability to perceive what they had believed to be concrete, and grasp the fact that there is no absolutely fixed identity. As such, Oh’s work is an enactment of the condition of a precarious, unstable being, fragile individuals, weak subjects, and the state of incompletion.

2. Individual and Ideology

“Ideology interpellates individuals as subjects.”

Ideology and the Ideological State Apparatuses (1970), Louis Althusser

Inhwan Oh had also worked on a project that involved looking for individuals and calling their names in 1996. He ran a classified advertisement where he looked for five artists – Roni Horn, Robert Gober, Nam June Paik, Haim Steinbach, and Cindy Sherman – in the Personal Ads section of the Village Voice, a weekly newspaper published in New York. The advertising copy he used was “Seeking the Real Roni Horn.” Unlike the common names he used in Korea, there are not many people with the name Roni Horn but matters became complicated with the inclusion of the adjective “real.” If the famous artist Roni Horn saw the ad, he might ask himself “Am I a fake?” and if an ordinary person saw it he or she might argue “the real artist Roni Horn is in me.” The person Oh really found through this project was not Roni Horn or Cindy Sherman but the artist himself. He unveiled his identity as a gay Korean male artist (GKM Artist) and came out through this advertisement. Afterwards, he has been defined as a “gay artist” above all context and homosexuality has become major keyword that defined his works.6)

His personal ad on the Village Voice was paradoxically a perfect medium for his coming out. “An individual” becomes a meaningful being when he or she is called by some “voice.” As seen in the poem, The Flower, any sort of “nomination” always occurs within the relationship with others, making any “personal relationship” theoretically impossible. It has thus always postulated the public domain beyond the personal boundary. A homosexual relationship is an immensely private affair of ‘loving someone’. However, this has been expanded into a comprehensive social scientific discourse encompassing issues of gender, human rights, religion, law, and politics. Louis Althusser defined the public system intervening in the private domain as the ‘Ideological State Apparatus’ (ISA).7) He distinguished it from the Repressive State Apparatus (RSA) referring to the public domain such as the army, prisons, police, courts, and the government. In contrast, he defined the Ideological State Apparatus as the ‘private domain’ that works through ideology such as family, religion, education, communication, and culture. The two modes of apparatus share a common goal for the reproduction of the relations of production, that is to say the sustainable maintaining of the pre-existent class structure in the frame of capitalism. While the RSA exercises power through both visible and invisible violence, the ISA works through interpellation.’8)

Althusser alluded that “ideology interpellates individuals as subjects.” However, he did not elaborate upon the difference between the ‘individual’ and the ‘subject’ but simply mentioned that an individual is ‘always already’ a subject. For instance, an individual is destined to have his ‘father’s name,’ have the identity anticipated by a specific family, and have his designated social position from the moment he is born. An individual who is born in this way adapts himself to the established order that languages and the mass media have infused in him and unconsciously accepts society’s dominant values and behavior patterns by internalizing his subjectivity as a sincere consumer in capitalism. Althusser defined this process or ritual in which an individual is shaped as “a concrete, personal, and irreplaceable subject” within the frames of religion, culture, education and family as ‘nomination.’ His ‘nomination’ has an affinity with Chun-su Kim’s The Flower, in that it is a decisive phase in which an insignificant being turns into a significant being. Moreover, this concept stresses the involvement of ideology, one of the Ideological State Apparatus, in the process that ‘an individual’ as a biological being becomes a cultural ‘subject’ while being incorporated into a pre-existent social order.

The structure of ‘nomination’ in Oh’s works apparently reveals the two aspects mentioned above: a bilateral process in which an individual becomes a subject; and the existence of Ideological State Apparatus intervening in this process and working in particular situation in Korea. ‘Names’ are a potent device to preserve the preexisting order of a patriarchal class society in Korea where the rule prohibiting marriage between men and women who had the same surname and ancestral home was abolished in the 21st century. As many as 11 names in his Name Project finally found their users. They really were the ‘most common names in Korea.’ But then again, more than 20 million people, almost half of the total population of Korea, use three major surnames (Kim, Lee, Park) out of the 286 surnames presently in use in Korea.9) Koreans inherit their fathers’ surnames that come from a pool of less than 300. As for their given names, one letter is decided by the letter of the names of relatives in the same generation of a clan while the other is usually chosen from a letter with an “auspicious” meaning. As a result, we Koreans are all born with a holy mission: we all have to be agile, upright, and wise.10)

Things of Friendship (2000-2008) demonstrates how an individual identity as part of a capitalistic society is defined by ‘industrial products,’ moving beyond family ideology of a patriarchal society. He searches for things both he and one of his acquaintances possess by searching every nook and cranny of his acquaintance’s home. He then arranges the discovered objects in order and photographs them. After returning home he takes out the same objects he possesses, arranges them in symmetrical juxtaposition with his acquaintance’s objects, and photographs them. The two sets of ‘things of friendship’ in the photographs displayed at the gallery are mirror images of each other. Those ‘things’ synecdochically indicate a ‘friendship’ between Oh and a specific person we do not know. Texts on contemporary art like The World of Nam June Paik, Art in Theory, and Minimalism as well as tripods, films, and slide boxes hint at the educational background and artistic tastes of a figure with the initials ‘KM’ and Inhwan Oh. However, ‘DD’ and Inhwan Oh who share the same laundry soap, salt, tickets for the New York subway, and a copy of the Spartacus International Gay Guide version 2001/2002 are ordinary people who commute by subway, cook food at home, and at times dream of overseas trip. The person of ‘Inhwan Oh’ appears as a different man whenever the mirror he faces changes. Things are not an outgrowth but a producer of his friendship. ‘Friendship’ is an outgrowth of ‘things.’

3. In the name of the father

A certificate tells me that I was born. I repudiate this certificate: I am not a poet, but a poem. A poem that is being written, even it looks like a subject.11)

The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis (1981), Jacques Lacan

Althusser asserted that the concept of the subject embraces both subjectivity and subjection.12) This means if someone calls my name, I naturally identify with the subject of the sentence and unconsciously bring myself to the position of the subject. The axis of the mechanism of such ‘nomination’ is language. Althusser’s subject theory formed in language submits to ideological nomination and combines with Jacques Lacan’s psychoanalysis. Lacan argued that the subject comes into being through one’s entry into symbolic order, the world of language and symbols. He expressed this in a terse statement, “I am not a poet, but a poem.” ‘A signified body,’ namely the subject, is formed as a result of innumerable writings by others on the sleek surface of the body as a biological being.

Since 2001 Oh began to install Where He Meets Him at different venues. He would write numerous letters on the ‘sleek surface’ of the museum floor with incense powder. The incense powder began to burn as soon as the exhibit opened, leaving indelible marks of letters like scars by the time the show came to an end. The letters whose meanings the ‘general public’ cannot grasp are the names of gay bars and clubs in the city of each exhibition. Art critic Jung Hyun referred to homosexuality as ‘unspeakable love’.13) Oh has engraved unspeakable letters otherwise prohibited from being written to preserve patriarchal order on the skin of the authoritative institution of the art museum in an extremely physical and destructive manner. Another Name Project, Ivan Party is also a work that involves writing names that should be prohibited or concealed. This work presents the poster for a year-end party he held from 2004 that he enjoyed with his gay friends. Participants in the party all signed their names and their signatures overlapped in such a way that they became unrecognizable. Speaking in the Althusserian way, they are those who show no response to the Ideological State Apparatus ‘nomination’. Translating it from a Lacanian perspective, they are those who do not enter the symbolic order of the dominant language.

Lacan proposed the subject’s growth and development theory through the reinterpretation of Sigmund Freud’s Oedipus complex.14) The classical Freudian psychoanalytic theory states that a young boy desires to have sexual relations with his mother and feels an impulse to remove his father in the pre-stage of an Oedipus complex which is composed of five psychosexual development stages. Afterwards, the boy notices that his mother has no penis and believes that she was castrated by his father as ‘punishment.’ Accordingly, the boy suppresses his desire for his mother due to the anxiety that he might also be castrated (known as castration anxiety), identifying himself with his father, and projects his feelings of love toward a girl other than his mother. This is the ‘normal’ growth that Freud denoted. Thus the most important key in the formation of a boy’s identity is the presence and absence of the penis.15)

Lacan reconsidered the meaning of the penis as something physical that can be seen. He implied that the value of the penis is absolute and the patriarchal social order in which the father’s authority has been firmly established has to be preceded for such gender difference to be valid. He asserted that the penis is ‘an improper physical symbol’ signifying a prominent social position and presented the ‘phallus,’ a privileged signifier, to replace it. He meant that the phallus is not an absolute, elemental thing being ‘signified’ but is the ‘signifier’ whose value is determined by external social factors. He alluded that the most important device to lend meaning and power to such an empty signifier is language. Language as a prerequisite for the subject enacts patriarchal laws, determines an individual’s sexual identity, and subordinates the individual to the system in the name of the father.16)

As it is widely known, a ‘father’s name’ (nom) stands for the ‘father’s prohibition’ (non). This is a metaphor for suppression and sacrifice as well as deficiency and loss innate in the process of subjectification through which one carries out a transition from a primal being to a meaningful one. Lacan used “a barred S” ($) as a way of symbolizing the subject who has been alienated and divided by language (or Althusser’s ideology). Lacan’s subject ($) is by nature, a ‘precarious, unstable’ being that cannot help but undergo the process of loss and deficiency. And yet, the real repressed by the father’s name and prohibition by no means disappears completely. Lacan stated that “something irregular, unutterable, and ineffable, the ‘aporia’ always appears in language”. As there are holes in the father’s net of laws, the real has consistently tried to disturb and overthrow a world of representations. This is the ‘return of the real.’

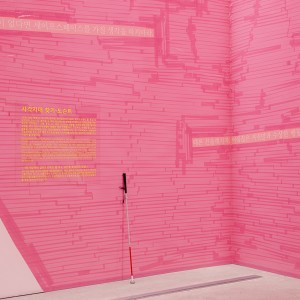

Oh’s Looking Out for Blind Spots is an embodiment of a bright return of the real. The CCTV cameras look down on the viewers from the high ceiling and keep an eye on subjects who have adapted themselves to the white tidy space. The monitors hung on the wall shows the viewers slowly walking around in the spotless gallery. The individual actually in this space comes to realize that it is completely different from the one on the monitor. The walls that remain out of the camera’s view are entirely covered with pink tape. The blind spots, namely the surplus space not caught by the camera, an area that resists the gaze of surveillance, and the residual domain that avoids the dominant system of representation are wider than we expected. The pink tape is an embodiment of the ‘other’ that has constantly fought for its presence despite being excluded from the nomination of ideology, has existed without being written as a symbol, and has been in language without having any property of language. The realm of the other is more spacious than we thought. That is why anyone can become the other in the social order of Korea where collectivism and patriarchy are still solid. Oh did not join any relevant official events and also did not appear in videos documenting the process of his work because he himself believes that he is in a blind spot, a surplus space the public gaze cannot catch.

4. HERE, THERE, HOMELESS

Inhwan Oh has been continuing on with the Street Writing Project since 2000. Oh spontaneously recreated English alphabet with things found on the streets then took photograph of it. He would then make words by arranging the photos. The materials he found are nothing more than wastes, including bread crumbs, fallen leaves, cigarette butts, and broken pieces of glass. They were perhaps very beautiful, useful, and precious things that had offered pleasure to their owners before they were thrown away. Oh called their names. He imparted meaning to them by creating words with the letters and transformed them into a work of art by displaying the words in a gallery. After Oh leaves the street, the letters become scattered in all directions. However, they are no longer the petals withered and fallen from a flower but are scattered fragments that were once part of a work of art. They form words like HERE, THERE, and HOMELESS. Perhaps Oh and the rest of us are insecure, precarious beings floating between meanings ‘without belonging to’ ‘here’ or ‘there’.