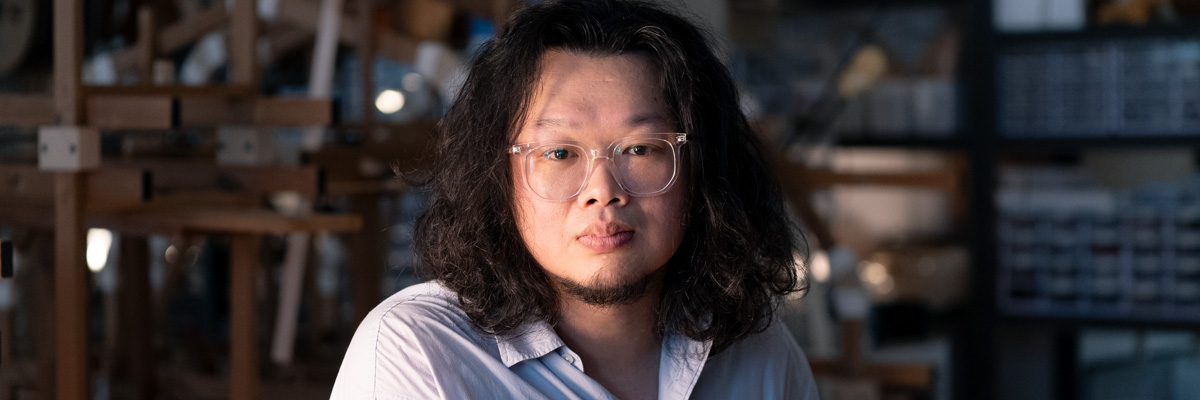

Yang Jung-uk

Interview

CV

Lives and works in Siheung

Education

2011 BFA in Sculpture, Kyungwon University, Seongnam, Korea

Selected Solo Exhibition

2022

Without Any Words, The SoSo, Seoul, Korea

2021

Maybe, It’s like that, OCI Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

2020

Scenery of dialogue, Bucheon Art Bunker B39, Bucheon, Korea

2019

We Placed the Photograph Taken Yesterday in Plain Sight, Gallery Hyundai, Seoul, Korea

2018

Looking at Today Through Yesterday’s Glasses, Sindoh Art Space, Seoul, Korea

We went to a small zoo and a smaller art museum on a windy day, Hwaseong cultural foundation, Hwaseong, Korea

2017

“Roland, I need it,” Domaine de Kerguéhennec, Bignan, France

2015

A Man Without Words, Doosan Gallery, New York, USA

Mr. A – the blind, retired masseur – now sells electric massagers, OCI Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

2013

The shop where we said mere “Hello,” Gallery SoSo, Paju, Korea

Selected Group Exhibition

2024

Korea Artist Prize 2024, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea

2022

My Your Memory, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea

Masquerade, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Gwachoen, Korea

Channel: Wave-Particle Duality, Changwon Sculpture Biennale 2022, Changwon, Korea

2021

Loss, Everything That Happened To Me, Daejeon Museum of Art, Daejeon, Korea

2020

RhythmScape, Ottawa Art Gallery, Ottawa, Canada

2019

APMAP 2019 Jeju, Osulloc Tea Museum, Jeju, Korea

Gentil, Gentle: The Advent of a New Community, MOCA Busan, Busan, Korea

2018

A Day for Counting Stars: The Story of You and Me, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Cheongju, Korea

Steel-Being, F1963, Busan, Korea

City Impression, 63ART, Seoul, Korea

The Architecture of Structure, Suwon Museum of Art, Suwon, Korea

That house, OCI Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

2017

Rhythm Scape, Korean Cultural Center, Tokyo, Japan

Blank Page, Kumho Museum, Seoul, Korea

2016

Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening, Gallery Hyundai, Seoul, Korea

2015

Rhythm Scape, Gyeonggi Museum of Modern Art, Ansan, Korea

Artist File 2015: Next Doors, The National Art Center, Tokyo, Japan / National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Gwacheon, Korea

Random Access, Nam June Paik Art Center, Yongin, Korea

2014

Low-Technology: Back To The Future, Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

The Brain, KAIST, Daejeon, Korea

Thoughts of Every Day, Datz Museum of Art, Gwangju, Korea

Everybody has a Story, Gyeonggi Museum of Modern Art, Ansan, Korea

How to hold your breath, Doosan Gallery, Seoul, Korea

2013

The 35th Joongang Fine Arts Prize, Hangaram Art Museum, Seoul, Korea

Mind Cloud, Sungkok Art museum, Seoul, Korea

2012

Variation, PS Sarubia, Seoul, Korea

2011

I’m Future, Kim Chong Yung Museum, Seoul, Korea

Class of 2011, Gallery Hyundai, Seoul, Korea

Boiling Point, Kunstdoc Gallery, Seoul, Korea

Selected Awards and Grants

2020

Kim Se-Choong Sculpture award, Korea

2018

Paradise Art lab, Korea

2017

SINAP (Sindoh Artist Support Program), Korea

2015

OCI Young Creatives, Korea

2013

The 35th Joongang Fine Arts Prize, Award for Excellence, Korea

Selected Residencies

2018

Incheon Art Platform, Incheon, Korea

2017

Domaine de Kerguéhennec, Bignan, France

2016

Gyeonggi Creation Center Artist-In-Residence, Ansan, Korea

2013

Goyang Residency, National Museum of Contemporary Art, Goyang, Korea

Selected Collections

National Museum of Contemporary Art, Korea

Gyeonggi Museum of Modern art, Korea

Seoul Museum of Art, Korea

OCI Museum of Art, Korea

Jeonnam Museum of Art, Korea

Critic 1

If This World Were the Answer, What Would the Question Be?1

Soyeon Kim (Poet)

Prologue. Perfect World: An Afternoon that Gradually Emerged and Then Gradually Faded Away

It was the last day of a trip. After spending over a month in a countryside village where I had rested to my heart’s content, had a little fun, and spent ample time reading and writing amid endless fields of rice paddies and farmland stretched out before me, that afternoon I thought to myself, Tomorrow, I’ll return home. I rode around the village on a bicycle I borrowed from the place I was staying. Knowing it was my last day, I found myself paying keen attention to my surroundings. As if having a long goodbye, I took everything in while pedaling ever so slowly. A single tree, a tuft of grass, a discarded chair, a dented sign, a broken streetlamp, a large spider and its web dangling beside it, moss wedged in the gate of a house, the scent of the wind licking my skin, the sun setting in a way that highlighted the silhouettes of the ripened rice paddies…even with nothing more than those familiar things that had always been there, it felt as though there was not enough time for me to say goodbye. Just then, a flock of wild geese began gathering and taking flight. Had you always been there, too? I wondered. Was it only me who had not noticed until now? The wild geese quietly folded in their wings and landed not far from me. They gathered around a puddle full of what appeared to be shiny black water, lowering their beaks to drink. If it had been yesterday or the day before yesterday, I might have paused for a moment, thought to myself, How cute, and moved on. But since I was leaving the next day, I took the time to watch them a little longer. One by one, raindrops began to fall into the puddle. The wild geese calmly stood in the rain before flying off again. Each raindrop that fell into the lonely puddle created concentric circles, which grew larger and larger before disappearing, only to be replaced by new ones, repeatedly, over and over. The circles were so perfectly shaped and the rhythm of each new raindrop breaking the perfection and forming a new circle so fitting that I parked my bicycle, crouched down at a distance. A child glanced at me and then approached the puddle. Kneeling down, she placed both hands on the ground before taking a paper boat from her pocket and setting it afloat in the puddle. The small boat, neither departing nor docking, bobbed gently, the paper rustling slightly. Workers carrying stacked roof tiles on their heads passed by and said something to the child, who responded with nothing more than a wide smile. When a voice called out from a distance a moment later, the child turned her head in that direction. This time, it sounded like a chorus of voices, as if many people were singing together. It seemed that they were calling for the child, who stood up, dusted off her hands, and ran toward the voices. I watched her back until she disappeared from sight. Then I sat there for quite some time, wondering whether I should take the paper boat with me or leave it where it was.

Recently, I suddenly recalled that long-forgotten day. The paper boat from that afternoon appeared vividly before my eyes, white and perfectly clear in my mind’s eye. I was overcome with a feeling like the one that child might have had when she folded that paper boat by hand and pulled it out of her pocket. I even felt a little like the puddle, which had been filled a touch higher than usual thanks to the rain that had fallen just in time for the child who had run outside to set the boat afloat. At the same time, I also felt like the house at the end of that road I was on, which accepted the image of the child, her back to the house, as she ran toward the voices calling to her, leaving the paper boat behind. The paper boat carried with it the gaze of a stranger, someone who had spent time there and who would soon no longer remain, someone who was quietly observing everything in that place. Even if I had not seen the paper boat that day, it would not have mattered. Yet because I did see the boat, it felt like I had spent a perfect day. A series of events that gradually emerged and then slowly faded away had happened at just the right time on a single afternoon. It was the ideal last day of a trip. If someone were to ask me what I did on the last day of my trip, I would have nothing to say other than that I rode a bicycle. But it was a day where a perfect world—like the concentric circles spreading out in the puddle—repeatedly appeared and disappeared.

1. Same/Similar/Alike, Two or Three: The Stories Passed on

One night, I was the last customer to have a meal at a restaurant, and in the umbrella stand, there was an umbrella that was not mine. At first glance, it looked like mine—the one I had brought there—but it was not. The restaurant owner suggested that I take the umbrella anyway, saying it was the right thing to do in such heavy rain. And so, awkwardly, I opened the unfamiliar umbrella and made it home safely. From that moment on, that umbrella lived as if my umbrella for much longer than my original one ever did, until it, too, eventually left me. I tend to lose umbrellas easily, but for some reason, I did not lose that one for a long time. The umbrella was not the only thing that found its way into my home in such a way. Long ago, lighters often appeared the same way. One day, I would dig through my bag, and several colorful lighters would rattle out. My friend’s cat, Pepper, also came into her life in a similar fashion, and has lived with her ever since. The mushrooms that occasionally sprout like umbrellas from the pot where my fern is planted are much the same.

After years of carefully tending to a plant that I received one time as a gift, I eventually came to repot it. I purposely divided it into two separate pots before giving one of the plants back to the very friend who had originally gifted it to me. Over the years, different friends would also give me plants which I would subsequently repot and give back to them. Some of these same friends immediately recognized it as the same plant they had once given me, while others just saw it as another potted plant altogether. Once, while joking around with a friend, we wondered what it would be like if we were to receive a child as a gift, raise the child as two separate children, and then return one as a gift. Our conversation spiraled into something far too problematic to handle. We touched on issues of individual reproduction, growth, caregiving, bonds, the identity of gifts and sharing, and bioethics, with our humor branching endlessly into these topics as if brushing against the farthest ends of human history. It felt as if our jokes had come full circle and had borne fruit in the small plant sitting between us. I am thinking of tucking this story away, like one of the small mushrooms that is secretly blooming in my flowerpot—perhaps inside a lightbulb socket or behind the wooden parts of Someone I Know, in His Garden I’ve Never Seen.

2. The Result: An Ear That Remains Forever, Even After the Story Ends

Sometimes, when someone excitedly shares a story, and I listen with joy, I wish that these stories would not just disappear into thin air. I wish that they could hide somewhere, only to resurface and continue drifting on as endless tales. Sometimes when I hear such a story, I feel that even when it ends, I want to remain there with that person, still smiling, still clapping, still moving my shoulders in delight—without needing a story to do so. It is the same with my poetry. I really wish that someone’s creative work could exist in such a form, made to float endlessly in the air like an infinite story. Even after the story has left, I want there to be something remaining, like a giant ear, staying in place, so that the story never fully fades away.

This happened on a train from Frankfurt to Munich once. My seat was one of those four-person face-to-face arrangements, and across from me sat an elderly couple. Tired from my busy schedule, I immediately plugged in my earphones, turned on some music, and closed my eyes. Even though the sound of conversation around me grew louder, I ignored it and drifted off to sleep. I dreamed of chatting and laughing with people, and when I woke up, the woman sitting next to me smiled and shrugged. Apparently, she believed I had been laughing at her joke. They were speaking in German, and since I hardly understand any German, I could not laugh even if I wanted to. Yet in my dream, I had been part of their group, talking and laughing together. The elderly couple sitting in front of me continued their conversation with a gentle yet seasoned rhythm. The woman next to me, constantly amazed, reacted to their stories with playful remarks. Her laptop work had long been forgotten, as she was captivated by the old man’s storytelling. I could not say for certain whether I had been laughing because of her jokes or not. It felt like I had, and yet it also seemed impossible. Fully awake now, I quietly observed their conversation; I studied their expressions, their tone, and their gestures. The conversation I observed had almost nothing to do with spoken language. I was the last one to leave our four-person seating area. When the announcement for my stop was made and I stood up, I noticed a large ear-like object, similar to a cushion, left behind on my seat. I did not know if the “ear” belonged to me, but I left it there as I stepped off the train.

As time has passed, I have come to summarize the story I heard that day like this: upon retiring, the elderly man bought an old house in the countryside to renovate as part of his plan to move there. However, nothing about the renovation went as expected. There were conflicts with the neighbors, with government offices, and even with the spirits that had lived in the house for generations. After making numerous compromises and adjustments, the house turned out quite different from the one he had originally planned. The woman sitting next to me was in awe every time she uncovered a nugget of wisdom hidden in the old man’s story, and he responded to her amazement with lighthearted jokes. She laughed heartily, and I laughed along with them.

3. The Weekend They Do Not Know About2: Urgent Matters Happen Everywhere

Once, I went to Odaesan Mountain with several colleagues. We chose to hike the Birobong trail, which takes about four hours, round trip. As we climbed the mountain slowly, we decided to rest by a stream. Two of my colleagues sat on a rock, pulling their feet out of their shoes and dipping them into the cool water. Another colleague unpacked some fruit from their bag and offered it around to all of us, while yet another colleague wandered off, talking on the phone at a distance. I sat by the stream with another one of my colleagues, dipping my hands into the water. The two colleagues with their feet in the stream were discussing their hiking boots, comparing the new features and talking about foot fatigue. The fruit that had been taken out lay on a flat rock, waiting for someone to reach for it. Meanwhile, the colleague who was on the phone drifted farther away, still engrossed in their conversation. All of a sudden, the colleague sitting with me and I noticed a baby grasshopper struggling in the water. In a rush of concern, I grabbed a nearby leaf and tried to scoop the tiny insect out of the stream. The baby grasshopper appeared more terrified by the approaching leaf than it had been while struggling in the stream. My colleague softly exclaimed, “Don’t be scared! We’re trying to help!” I joined in, also speaking gently, “Climb onto this!” Miraculously, as if it understood our words, the baby grasshopper crawled onto the leaf and was finally placed safely on solid ground. However, once on the ground, it simply sat there, unmoving. Whether it was because its body was soaked or it was trying to assess the situation, it nonetheless stayed still. A few seconds passed before the grasshopper lifted its front legs and reached up to touch its antennae. It seemed that the antennae, which should have been spread apart in a “V” shape, were stuck together because of the water, making it difficult for the grasshopper to move. It kept using its front legs to wipe the moisture away, struggling to separate the stuck antennae. The grasshopper’s movements became more frantic. We held our breath, watching carefully so as not to disturb it. The baby grasshopper then became cautious all of a sudden. Very slowly, it began to move its legs and carefully inserted them between its stuck antennae. Like an elderly woman carefully threading a needle—putting her magnifying eyeglasses to her nose, moistening the thread with her saliva, straightening it with her fingers, and finally threading it through with trembling hands—the baby grasshopper succeeded in restoring its antennae to a V-shape. With its antennae boldly pointing forward, the grasshopper suddenly flew off into the distance. My colleague and I cheered simultaneously, and our fellow hikers, who had been resting nearby, looked at us in surprise, startled, just like the baby grasshopper had been after being freshly rescued from the water. After descending the mountain, I could not engage in conversation with the group even though we had gone to a place we were all looking forward to going. Still, the others managed to have meaningful discussions and supposedly found a breakthrough to a project we had been grappling with for quite a long time. For that colleague and I who had shared the experience with the baby grasshopper, however, we only talked to one another in hushed voices about the grasshopper and how it flew away with its V-shaped antennae intact.

4. Socks: Just Like Bangs Grow Up Soon,3 You and I

I once traveled quite a distance to visit a friend who had been bedridden for years after surviving a horrible accident, undergoing major surgery, and coming close to death. At the time, even without a wheelchair or crutches, my friend was able to walk pretty well beside me. The morning after we had spent the night together catching up, my friend sat on the floor, crouching while putting on socks, and said, “It’s such a joy to be able to put on socks by myself.” The act of bending one’s back to put on socks is something only those with healthy backs can do, but only those who have been injured, like my friend, can truly understand this seemingly obvious fact. While waving a pair of socks in my hand, I joked, “If doing this makes you that happy, do you want to put on an extra pair?” Ever since then, whenever I put on socks, I think of that time in my friend’s life when she was struggling with her physical ailment; the slow, day-by-day healing of a broken body held together by screws; the patience my friend exhibited while enduring that torturously long period of her life; the tremendous effort it all required.

5. If You Have Ever Seen Something That Stood Still4: That Place Becomes the Furthest Edge You Know, Like a Beach or a Cliff

One day, while taking a walk around the neighborhood, I found what appeared to be a discarded soccer ball in the bushes. The outer layer was peeling off and the stitches were coming undone. I looked at it for a moment and walked on. Seasons changed, and then early one morning after a heavy snowfall, I was taking another walk around the neighborhood, enjoying the act of leaving my footprints in the fresh snow and the accompanying sound it made when, in a world covered as if with a white blanket, I saw a round patch of brown earth exposed. The soccer ball that had been there suddenly came to mind. Thanks to the round spot of dirt showing through the white snow, I remembered the old soccer ball. I started wondering where it might have gone. Maybe someone kicked it, sending it flying high in an arc. Imagining an invisible arc in the air, I continued thinking about the ball. I imagined it flying off somewhere and resting quietly with a soft layer of snow covering it on a day when the snow had melted and then fallen again, only to be kicked once more by someone. I imagined a yellow patch of grass was concealing the soccer ball and its torn stitches somewhere. Beside the round patch of dirt, there was a fist-sized stone covered in a round cap of snow. I picked up the stone. Now, next to the big round patch of dirt, there was also a small round patch. I decided to take the stone home—the stone that had been guarding the side of the soccer ball. It was the stone that had guarded the soccer ball, the one that had shown me the imaginary arc in the air. At home, I placed the stone on my desk and started writing some poems. As I thought about the soccer ball and the arc, I began feeling like I had become a baseball outfielder. When I opened my notebook, imagination took over and a bunch of old baseballs, their seams undone, tumbled out in my mind’s eye. All of a sudden, I was standing at the furthest point of a field I knew, wearing a glove and guarding the edge of the field. Baseballs kept flying in arcs, and I stretched out my arms, trying to catch them all. Some balls I missed, but I did not mind. The missed balls, in their own way, would roll off somewhere and form a round patch of dirt like the soccer ball I had once seen, wearing the fallen snow like a beret.

Could I ever properly convey such a story to someone? Perhaps while drinking tea, or during brief moments of small talk in the middle of a conversation about work. I could, if I wanted to, but I have chosen not to. These are the kinds of experiences that cannot be conveyed through words—stories that could never be fully understood if told. They are more fragile and layered than stories that can be shared, and they are felt only faintly, like someone’s breath. Stories that would not change anything, even if someone told them out loud.

6. The Invisible Part of Labor

For some time, after getting home from work, I would sit down to write this piece, little by little, at night. When the sound of cars outside the open window grew louder, I would stick my head out and take a look. I could see a line of trucks with their headlights on or a delivery vehicle entering my apartment complex. In the morning, after opening the front door, items I had ordered would be waiting in boxes. I would pick up the boxes, bring them inside, and step back out into the hallway. On one such occasion, I could smell the faint scent of bleach. Standing on the freshly cleaned floor, I pressed the elevator button. An announcement came on and mentioned that several trees had fallen due to the typhoon the night before. At the entrance of the apartment complex, two workers stood next to one of the fallen trees. I thought to myself that by the time I returned home, the trees would be standing upright again. Road maintenance on the highway asphalt usually happened at night, at which time the cracked and worn road was transformed into a glossy, new road. Workers, equipped with their tools, must have gone to the damaged highway in the middle of the night. They likely returned home only at dawn, finally laying down on their back, which had been bent over throughout the night, to rest. Every night, I continue to write, little by little. There are more words I have erased than I have kept. There are more thoughts that have disappeared while trying to emerge than those that have actually surfaced. Experiences and memories flicker in and out of existence, never quite materializing into sentences. If they were made of fluorescent material, my body, while writing in the dark, would be glowing in the night.

7. Gestures: The Encounter between What Is Seen and What Cannot Be Seen

I want to call this a gesture, not just a movement. A single scene and a single story transform like a tree walking with its roots, its expressions, movements, and emotions becoming interwoven with the body’s joints. This is how a gesture begins to form. The stagnant air scatters, moving restlessly as it starts to weave a space different from before. Any gesture takes on significantly more meaning with the help of language. It captures and preserves, without omission, the first scene imagined by the artist, scattering it anew into the aforementioned space—and all without confining it to anything material while also not relying on any notion of the immaterial. A gesture realizes the encounter of the material and the immaterial. Landscapes we should have long noticed emerge in relief from the void. Stories that cannot be clear or concrete, the missing pieces, meet us in this way.

Epilogue. A World that Cannot Be Complete: Beauty Shaped by What Never Stops and Repeats Eternally

When a piece of art rests under a dim light, stories like the ones above drift through the softly lit space. They flow gently, with little strength to grasp anything in their path or simply continue on a slightly descending slope—and without any desire to dominate anyone’s ear or stir a person’s heart. Fleeting and weak, they creak as they move along, constantly repeating themselves. Yet there is a belief in the weight that comes from the eternal repetition of such fleeting and powerless movements. Though no words are exchanged, a conversation flows and lingers around us. It seems that when we realize there is a story we want to tell, this story begins to move, intertwining with our own. These movements are designed within a non-sophisticated calculation. Movement, while it is something realized, also functions as a body language that initiates dialogue. At the same time, it also works as an invitation, suggesting that we bring forth dialogue. It is a mechanism that responds to the stories we have long wanted to tell. Like nodding your head, like spreading your lips into a glorious smile. After we offer stories that we have never spoken before to this place, we become people who have experienced a conversation we have never had before.

Scenes we had certainly seen, yet completely forgotten, omitted from our memory, or deliberately shook our heads at, wishing to pretend we had never seen them. Stories that, even if told in the language pervading our everyday lives, would hold no meaning or evoke no emotion. These are not merely stories but the backgrounds of stories. Like a nut and bolt, the stories and their backgrounds fit together tightly. The protagonist of a story may become its background, the observer may become the protagonist, and the listener may become the main character. In other words, there is a rich tapestry of stories around us at any given moment. Stories like insects with too many legs, trees with too many arms, the hidden veins on the back of a leaf hanging from a branch, or capillaries embedded deep within every corner of our bodies. They were already stories, but have been waiting a very long time to become stories in the proper sense. Stories that will continue to live on even after they are told and the listener has disappeared. Today, I stand before this work as someone who has received a message that these stories are safe somewhere.

1. Soyeon Kim, “Worship” in Dear i (Seoul: Achimdal Books, 2018), 13.

2. Adapted from the title of Yang Jung-uk’s work Only the Turtle Does Not Know Our Weekends.

3. Adapted from the title of Yang Jung-uk’s work Bangs Grow Up Soon.

4. Adapted from the title of Yang Jung-uk’s work I Once Saw a Man Who Stood Still.

Critic 2

Faceless Portraits Drawn by Storytelling Machines

Im Sue Lee (Professor, Department of Art History and Theory, Hongik University)

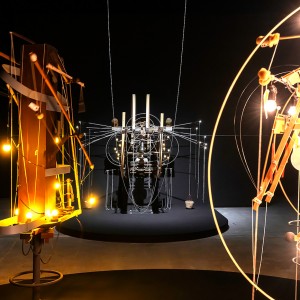

Yang Jung-uk’s work is about storytelling that starts with people. His devices, made of wood and motors, convey stories through the space they occupy, their movements, and the sounds they make. Yang’s work represents a body, and the body that occupies an exhibition space speaks through its movements. Thus, his artworks can be called “storytelling machines.” Yang’s storytelling machines, while occupying spaces, imply our body and awaken an awareness of its presence. The stories conveyed through their balanced structures and repetitive movements are less grand epics and more like small talk from everyday life, a warm gesture of comfort, or a heartfelt message that needs to be conveyed. The reason Yang chose moving machines as a medium for storytelling, as opposed to speaking or writing, is probably for the purpose of more directly communicating people’s emotions and their sense of life. Ultimately, Yang’s work does not merely show an interest in experiments dealing with mechanical aesthetics, technological media functions, or the existence of technological objects. Rather, he displays an interest in a broad intersubjectivity that encompasses not only the human subject but also the others and the environment surrounding them.

1. Storytelling Machines from Life

While considering the machinic dimension of subjectivation, the noted French psychoanalyst and philosopher Felix Guattari pointed out that in today’s world, where digital technology has become commonplace, techno-logical machines of information and communication operate at the heart of human subjectivity. These machines function not only within their memory and intelligence but also within their sensibility, affects and unconscious fantasms. Attempts to redefine subjectivity may begin by emphasizing the heterogeneity of the components leading to the production of subjectivity.1 Yang’s storytelling machines emerge as an example of aesthetic machines to replace capital, information machines, and communication machines. Specifically, they create moments of rupture and changes by assigning heterogeneous layers to the various elements that produce subjectivity. Through the mobilization of all rhetoric, Yang’s storytelling machines tell stories about people in specific situations.

The purpose of storytelling in artworks is profoundly classical. Throughout the long history of art, many paintings and sculptures considered great have conveyed stories about remarkable figures, historical events, and the nature created by God—and are ultimately meant to be remembered and reflected upon for eternity. To achieve this, artists have invested in relentless training and extensive resources to embody beautiful and idealized bodies. Yang Jung-uk is no different in this regard. He also dedicates meticulous effort and time to his storytelling. However, the stories produced and conveyed by his works are drawn from observations and imaginations about the everyday people he encounters and the subtle experiences of his surroundings. Consequently, his works are a form of storytelling that begin with people and can be considered as a kind of portrait-making.

Yang’s storytelling begins with observations about others and reflections on daily life, including his own actions and words. He describes what drives and guides this process as a “soft heart” toward his subjects. His works portray subjects such as random people he meets from specific professions, family members with whom he shares intimate relationships, and the true selves of all these people, which he then uncovers when looking back on them, along with parts of his resonating heart from those moments. Not only does Yang exhibit a tender care toward these subjects, but he also employs his vivid imagination to craft stories about them. Indeed, his works produce stories by adhering to the conventions of formative symbols instead of following the structure of linguistic symbols.

For his art, he employs moving devices using wood and motors. Years ago, the genesis of such works was an automaton created as a small gift that evoked emotion. Later, he created a mechanical device through careful observation of the movement of bodies—human or nonhuman—with the aim of capturing even the movement of the mind that arose from it. The following artworks were titled in a way that allowed the viewer to infer both a character and the situation they were in: Adversity Whispers That There Is Hope (2011), Three Workmen I Came to Know Only in the Evening (2013), the Standing Workers series (2015, 2022), Massage Machines Don’t Know What Your Loved One’s Shoulders Are Like (2015), and He Explained for a Long Time Over a Corded Telephone with a Long Cord (2016). Furthermore, the themes of his works gradually expanded from the observer’s position to the positions and exchanges within interactive relationships, as seen in the Scenery of Dialogue series (2018–2019), You Said to the Side, and I Said to the Left (2021), and We Hugged Yesterday Tightly, Sat Cramped Up, and Looked in a Familiar Direction (2022). A more recent work, Someone I Know, in His Garden I’ve Never Seen (2024), conveys a story about a person through the landscape he created.

The technology used in Yang’s works is minimal—just enough to realize his ideas—yet still manages to preserve “humane time” and allow the energy of love to gather. He describes the technology he uses as the bare minimum, essentially a tool acquired through lived experience, and the machines moved by this technology are what he calls “machines of sincerity.” Rather than creating automated machines that no longer require any human touch, he creates machines that need human care and retain a sense of warmth.

Yang’s storytelling machines disappear after being installed once. If a piece does not find a place to be housed or a collector after its initial installation, it is disassembled, so it continues to exist only in the artist’s mind. The physical structure of the work is not stored or preserved to be exhibited again in the same form. Instead, Yang relies on his memory to recreate it. Since there is no detailed, standardized blueprint that someone else could use to replicate his work, only the artist himself can recreate it. This situation is akin to a storyteller narrating a story and then repeating it in a different version. The landscapes of the arduous lives of myriad professionals in industrial society, as well as the scenes of deeply personal experiences, are captured through momentary intuition and unfold as stories that transform into encounters between bodies in continuous time through the movement of spatial devices.

2. Moving Machines, Speaking Bodies

Yang Jung-uk’s works begin with movement recalled from memories of observation. By materializing the image of a character into a moving device, the artwork transforms into a body that moves and speaks to the viewer. The corporeality of this device exists as a distinct physical presence in the exhibition space, connecting with a situation that is perceived simultaneously through sight and touch. The world we habitually perceive through our bodies forms our phenomenological presence. At this moment, the physical space, the concrete objects within it, and the subject experiencing those objects become crucial elements of the work. This explains why Yang, who began his artistic journey through painting, has moved beyond the flat surface to create three-dimensional works. From a single observation, he imagines the image of an object and brings it into reality through movement.

While many of the machines we encounter today function as mysterious black boxes, with their inner workings hidden, the machines Yang creates openly reveal their dynamic structures, showcasing the mechanism that drive them. The process through which Yang’s storytelling machines are organized is closely related to their materiality. In other words, the materiality of the machines is directly connected to the production of stories. What connects the materiality of the machines and the stories is the flow of sensation and affects. Each one of his machines is placed as a solid object in a real space. Its parts are connected through physical exchanges of forces, while the mutual conversions between rotary and linear motions express particular bodily movement. Horizontal, vertical, and circular substructures with motors are connected to a whole wooden frame by wooden joints, bearings, and strings, all of them moving in repetitive cycles of relaxation and tension. Lamps and other materials attached in various spots mediate the flow of movement and respond to the intensity of energy.

As such, Yang’s machines convey stories through visual, tactile, and auditory elements. The artist profoundly contemplates a single object of observation, but in the actual artwork, he incorporates non-conceptual elements. The forms and structures, immediately grasped through vision, allow viewers to perceive how the work operates, and the perceived movement engages not only the eyes but also the entire body of the viewer, making the experience more tactile than purely visual. Yang Jung-uk’s machines mimic bones, ligaments, muscles, and a number of sensory organs, stimulating a range of senses simultaneously through the movement of motors, sounds, and vibrations. The reason Yang originally chose wood as his primary material is that it is a material that invites the act of touching. He creates his own imaginative world and objects by engaging with the state of things as sensed by the hand, the space around us as perceived through the body, and the information received through hearing. A person and the environment in which the person stands are transformed into a mechanical structure, and in this process, the two distinguished elements become interdependent due to the dimension of alterity that Guattari describes as inherent in the operation of machines.2

The reason why Yang’s machines, despite occupying physical spaces and possessing a strong concreteness, retreat into an imaginary dimension lies in the fact that these machines are storytelling machines. They are not only mechanical devices but also abstract machines with discursive capabilities. Yang’s machines speak to us from between real and imagined spaces. In contrast to the digital devices we use daily to speak to someone, and which rely on virtual space as well as the arrangement of fragmented signals, Yang’s storytelling machines are firmly placed in actual spaces, guiding viewers into a realm of imagination. From the memory of a moment when the artist encountered another person, an icon or image emerges, which is then transformed into nuances of form and color imbued with emotion and feeling, and ultimately expressed through the structure and movement of a machine.

The light that illuminates an artwork placed on the floor, and the shadows it casts, serve as indicators of the surrounding physical space while simultaneously transforming the work into an imaginative performer. The light and shadows create a stage that facilitates the encounter between the viewer and the piece. This stage then allows the exhibited work to oscillate between two dimensions: one is the solid body of its physical presence, the other is the narrative unfolded by its “script.” In this way, the light and shadows of the real space construct an imaginary space, and the movement within the actual space slides into the realm of imagination because, in the end, the artist’s goal is to tell a story.

Yang’s storytelling machine does not present a contemplative, representational image to the viewer. Rather, it confronts the viewer with a subject that takes on the structure of a moving machine. By placing viewers in front of the vector of subjectification, it enables them to be reborn as a new subject—not through linguistic cognition but through emotional perception—within a relationship connected to others and within the presence of the world. This process aligns with what Guattari called “pathic subjectivation,”3 or the foundation of all modes of subjectivation. Thus, Yang’s machine functions not only as a physical arrangement of elements but also as an abstract machine that generates meaning through the interplay and movement of its numerous components. Furthermore, it appears as the alterity of viewers, enabling self-production through intersubjectivity.4

3. The Faceless Portraits Drawn by Storytelling Machines

The stories conveyed by Yang Jung-uk’s machines are about the reality of a subject. Earlier, we noted that Yang’s works are a form of storytelling that begin with people, rendering them a kind of portrait-making. The artist imagines the material structure and movement of his works based on his observations of the people he encounters in everyday life and the emotions they evoke. Put another way, this portrait-making does not start from the face but rather from the body—its posture, movement, tension, and relaxation. Yang’s storytelling machines convey their stories not through symbols in language or images but through a pre-signifying regime of signs, such as gestures, rhythms, noises, and light. As a result, the story transmitted by these machines are something to be experienced. And because the stories of the observed figures, the presence of the moving body, and the dimensions of imaginative expression are intertwined, Yang’s machines become something strange—neither fantastical bodies of illusion nor rational mechanical devices.

Yang’s machines form signifiance and the strata of subjectification, which Gilles Deleuze, another French philosopher, and Guattari emphasize as two distinct axes in the regime of signs. For the signifiers inscribed to construct a story, as well as for the subjectification derived from the consciousness and affects formed by the arrangement and movement of the machine’s pre-signifying elements, the artwork needs a “white wall” for inscribing signifiers and a “black hole” of subjectification for positioning consciousness, affects, and excesses. Deleuze and Guattari both mention a face that these two layers of signifiance and subjectification produce, and this is born from an abstract machine that they call the “faciality.” This abstract machine of faciality operates according to the needs of economics, collectives, and power, producing an unindividualized face. In fact, this machine creates a system of a black hole and a white wall, thereby enabling the social production of faces. However, a machine that escapes from this social production of faces produces a deterritorialized face. The deterritorialized face includes not only the eyes, nose, and mouth but also the face-like chest, hands, entire body, and even the tools themselves. By distancing itself from the signifiers that engage with the facialized body, the body can be decoded.5 With respect to Yang Jung-uk’s machines, they go beyond the deterritorialized face that Deleuze and Guattari discuss, performing a type of portrait-making through the decoding of a faceless body. Instead of creating a face by imprinting two eyes or erecting a white wall to imprint the eyes on, Yang assembles workable limbs.

The strange portraits drawn by these machines are constructed along two axes: one is the axis of signifiance through storytelling, while the other is the axis of subjectification through mechanical movement. The story transmitted by such a machine begins with a sentence presented in the title of the artwork. Each title encapsulates a scene or a moment of intuition, with the story starting in the title, such as Where Do People Go after Lunch? (2012), The Three Siblings Are on Their Way Home, But It Feels Like They Are Going to the Store (2013), Only the Turtle Does Not Know Our Weekends (2014), or Did Your Father Sleep Well All Week? (2016). From these storytelling machines, a balance is struck between reality and imagination, and from this balance emerges pathos. Yet this intensity does not stem from facial expressions but actually from the complex ritornello created by the fragmented body. Guattari’s ritornello is a repetitive continuum that crystallizes existential affects, encompassing dimensions of sound, emotion, and the face that continuously permeate one another.6 Essentially, the movement created by Yang Jung-uk’s machines is this very ritornello.

Yang Jung-uk seeks to find the tension and balance between intuition, stories, and effects as he constructs his machines from fragments of divided bodies. These machines are devices of deterritorialized faciality on a deeply personal level. They are not only arrangements of physical elements but also aesthetic machines that carry out a literary mission while offering sensory experiences at the same time. Through these machines, the artist envisions the expansion of tense relationships, along with the diversification of senses and meaning. The portrait drawn by a storytelling machine is depicted through a ritornello of decoded bodies within a single story. As such, the story, which resides in the realm of language, is brought into reality through movement within physical space. Unlike fleeting stories generated by digital devices and networks, the storytelling machine employs a story that repeats endlessly. At its core, it tells a story that begins with a single observation in motion—through an embodied repetitive structure, just like the stories that have been repeatedly told since the earliest times when human experience and memory were transmitted in words.

In this sense, Yang Jung-uk’s works can be described as faceless portraits drawn by storytelling machines. These portraits, experienced alongside the viewer, offer insights into life and humanity through intersubjectivity. They resemble the strange tremor and shock one feels when gazing at their own face in the mirror, when interacting with family members, when encountering others throughout life, or when casually reflecting on the surrounding landscape. However, instead of a chilling black hole and a white wall, Yang’s machines reveal gestures and sounds that are released upon their deconstruction. What, then, does this repetition ultimately reveal? Could it be a portrait of the human being observed through the black hole’s gaze—a glimpse of life’s truth?