Jiyoung Yoon

Interview

CV

jiyoungyoon.com

Education

2013

MFA in Sculpture, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, USA

2010

BFA in Sculpture, Hongik University, Seoul, Korea

Selected Solo Exhibition

2021

Yellow Blues_, One And J. Gallery, Seoul, Korea

2015

A Single leg of Moderate Speed, Being&Thing Archive, Seoul, Korea

2014

Glorious Magnificent, Mana Contemporary, Chicago, USA

Selected Group Exhibition

2024

Korea Artist Prize 2024, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea

2022

On the Road, 5.18 Memorial Cultural Center

LIFE-SIZE, ONEROOM, Seoul, Korea

The Gesture of Images, PIBI Gallery, Seoul, Korea

2021

SIDE-WALK, Windmill, Seoul, Korea

Young Korean Artists 2021, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Gwacheon, Korea

2020

Art and Energy, Jeonbuk Province Art Museum, Wanju, Korea

We Are Linked, Seosomun Shrine History Museum, Seoul, Korea

This Event, Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

Us Against You, Gyeonggi Museum of Modern Art, Ansan, Korea

2019

Night Turns to Day, Art Sonje Center, Seoul, Korea

Will you still love me tomorrow?, Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

Ecological Sense, Nam June Paik Art Center, Yongin, Korea

We Don’t Really Die, One and J. Gallery, Seoul, Korea

2018

Acrobatic Cosmos: b-o-o-k, CHAPTER II, Seoul, Korea

Genre Allegory – The Sculptural, Total Museum of Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea

Monstrous Moonshine, NAVER Partner Square, Gwangju, Korea

Instruction for the Audience, SeMA Bunker, Seoul, Korea

Acrobatic Cosmos, One and J. Gallery, Seoul, Korea

2017

Floor Plan Cabinet, Audio Visual Pavilion, Seoul, Korea

2016

No Longer Objects, Buk-Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

Scatter Gather, Insa Art Space, Seoul, Korea

After Dinner, Before Dancing, Chicago Filmmakers, Chicago, USA

Discrete Use of Reality, DOOSAN Gallery, Seoul, Korea

2015

Physical Information, Defibrillator Gallery, Chicago, USA

Future Proof, LODGE Gallery, Chicago, USA

2014

Surrealism and War, National Veterans Art Museum, Chicago, USA

Forced Air, ACRE Projects, Chicago, USA

Upon The Skin, 49B Studios, Brooklyn, USA

2013

In Plain Cloak, The Bike Room Gallery, Chicago, USA

2010

2010 New Artists, Kim Chong Yung Museum, Seoul, Korea

Selected Awards / Residencies

2023

DAAD Artists in Berlin, Berlin, Germany

2020-2021

Incheon Art Platform, Incheon, Korea

2019

SeMA Nanji Residency, Seoul, Korea

2017-2018

Seoul Art Space Geumcheon, Seoul, Korea

2016

MMCA Residency Goyang, Goyang, Korea

2014

MacDowell, Peterborough, USA

Selected Collections

Suwon Museum of Art, Korea

Seoul Museum of Art, Korea

Critic 1

The Sides We Cannot See Do Exist

Junghyun Kim (Art Critic)

“Can we only wish?” Is there anything that people can do as they see, hear about, and experience in close or personal ways the endless crises, frustrations, and suffering happening around them? The questions and the artwork that Jiyoung Yoon latches onto have to do with the wishing heart. To assuage my struggles with the need to understand something about her completed work without being able to view it, I read some papers about the “ex-voto” tradition, which Yoon mentioned as a key reference in her recent work. As I did, a few odd questions came to my mind. How can we avoid despairing? How can we wish again while experiencing all this pain? How can we say that it’s not over? A universal part of human consciousness is the desire to allay our fears of death. We long for existence beyond or transcending death; we have the spiritual idea of being alive in order to stave off awareness of the body moving closer to death with each day. In connection with this, religion and ritual have formed time-honored cultures associated with the human race. But how can we see beyond the pain and speak of the world’s continued existence?

While we often hear about physical symptoms that cause intense pain as the stomach contracts, there is no way of actually knowing them without experiencing them firsthand. Even if we know going in, the experience is (might be) still unsettling and painful each time. Our consciousness blurs into a fog as we feel dizziness and an intense pain that seems to take our breath away. “Physical pain is not about or directed toward anything.” Pain overwhelms all things, erasing everything except itself. The declaration that there is nothing beyond pain is something the pain has brought about. As a guide, we might think of these words: “[T]he human attempt to reverse the de-objectifying work of pain by forcing ‘pain itself’ into the avenues of objectification is a project laden with practical and ethical consequence.”1 Pain and objects—but what is pain, and how can we perceive it? Perhaps a more direct and practical endeavor is to ask how pain creates objects. It is a matter of looking at what we have seen while acutely aware of pain’s self-silencing properties.

“The hole represents fear, pain, and death.” Jiyoung Yoon looks at white seashells. As she threads them into a necklace through holes bored into them, her hands stop moving. “Why did this hole arise? A delicate hole clearly appears bored from outside.” The fate of some mollusk that was victimized by a predator’s artisanal aggressions—removing the flesh and leaving only a perforated shell behind—leads the sculptor to contemplate her medium’s “exterior and interior, its hidden structures, and their respective roles.”2 Here, fragments of thoughts from the past and future are interwoven with the hole and its depth as a focus of fear, pain, and death. When pain leads us to wish for and rely on something to escape from its grip, this creates a belief that objectifies pain. So when the artist Jiyoung Yoon speaks of “wishing” rather than “expressing,” our first focus is on her visual methodology and its attempts not to preach a belief system, but to show the structures of will and reliance that create belief.

The Dialectic of Capability and Vulnerability

The balance has already broken down. The moment we become aware that one side is uncontrollably tilting, this ironically causes a clear premonition of the unfolding of one’s own language. This is a description of Jiyoung Yoon’s early work. A prominent example of this—which transformed into a series rather than an isolated creation—is Dear Peer Artists (2014), which has to do with crisis. The crisis was an issue that the artist herself faced, relating to the precariousness of life as an artist. At the same time, it was also an issue shared with many other artists in a similar position of having decided to live the creative life. How does an artist live? According to longstanding psychological theory, human desires have a stepwise nature, where lower-stage desires must be met before the next stages can be achieved. In contrast with biological drives or the drive for security, the drive of artistic creation relates to higher-level stages such as the desire for affection and affiliation, the desire for respect, and the desire for self-actualization. Thus, if a person possesses the creative drive, we have to assume that their lower-level desires have already been met. As we all know, this is not the case in reality.

For Dear Peer Artists 1_Maslow, Bullshit (2014), Yoon created a three-dimensional sculpture with a two-dimensional diagram as a reference. This is a critical interpretation of the classic pyramid structure in the psychologist Abraham H. Maslow’s five-stage hierarchy of needs, with an approach that incorporates the horizontal framework of a radial diagram. The work was designed with five globes inflated by means of an air pump: each of them presses against the others until the weakest pops. While the criticism of fallacies in the hierarchy of needs is apt, it cannot be said that the life of an artist driven by the desire to create is “going just fine.” Yoon established a theory based on her own intuitions, in which differing drives exist in a relationship that is horizontal but necessarily involves mutual pressure, until the equilibrium finally breaks down and one side or another bursts. Each individual drive can expand to the limit of its capabilities—but because the different parts are controlling each other, no one of them can grow endlessly, nor can all of them be fulfilled to the maximum. Yoon’s work goes beyond referencing a diagram to conceptualize the expanding and mutually pressuring aspects of neighboring sculptures. Through its logical structure, it effectively conveys a psychological message.

This leads to a question: how does the individual go on once one side has broken down? If the central structure breaks apart, the only way to sustain the shape is to rely on a new structure provided from outside. Dear Peer Artists 2_Spherecal-bridge-moment (2014) centers on a spherical structure with holes bored into it. Strings pass through the holes and wrap around the sculpture’s body; within the hollow interior, they are likely to be intricately entangled. Wooden spikes of differing sizes and textures pass among the holes and strings, bending and breaking in the process. Also attached is an oval structure that faces the ground with its head slightly raised, fixing the sphere in place while also suggesting movement. Positing that artists play a mediating role in social ruptures as their lives are driven by unknown motivations that are separate from the fulfillment or alleviation of social needs, Yoon conceived a structure in which an external input is outputted through the outwardly soft, inwardly tough medium of aqua resin.

Jiyoung Yoon’s visual language, which adeptly applies social and psychological reflection to the sculpture medium’s explorations of physical concepts, has been visible since the early stages of her career. One visual methodology—that of dangling—has become a key visual language, which has undergone different variations. As an example, consider how Yoon approaches the written world in her various works, as seen in the aforementioned titles. In the Korean titles of her works Dear Peer Artists 2_Spherecal-bridge-moment and A Single Leg of Moderate Speed (2015), she runs the words together without spacing; in other cases, like That that is is that that is not is not is that it it is (2016), she disregards set principles of separation, separating syllables with underlines to render the written word strange. In a similar way to this linking of syllables or placement of them in new relationships, Yoon has used the physical shapes of her work and their suspension in the air to show the part and the whole in a special relationship of interconnection.

Traditionally, sculptures are placed on the floor. This relationship to the ground may be seen as establishing one of the fundamental conditions of the sculpture medium. Looking back at the history of art in the modern era, we see how sculpture acquired the pedestal as an indicator of physical independence once it spun off from its status as a decorative component of architecture. In the modernist art spearheaded by Western countries, the pedestal was reconsidered as part of the sculpture rather than an accessory. Not only have sculptures been presented together with various aesthetic supports that are integrated with their main structure, but they have also gained the ability to come down from their pedestal. As we break away from the practice in which the sculpture marks off a separate domain, the medium can be infused back into architecture and the landscape. When we consider the history of expanded forms of representation in contemporary art, our interest in the internal properties of sculpture seems like something written on pages from long ago.

This is one reason for focusing on Jiyoung Yoon’s approach to visual practice. While she carries on the classical virtues of the sculpture with her ongoing explorations of and experiments with different physical materials, she has also broken away from conventional sculptural methods to engage in creative, conceptual investigations of related practices. In the possibilities harbored by the visual language of sculpture as a classical medium, she sees the groundwork for contemporary artistic practice. The key element of the expansion in her work is not about the space or installation context that the sculpture physically occupies. It lies in her contemplation of the sculpture’s structure and the potential for sensory expansion of this sculptural examination. Returning to the matter of “dangling” in this light, we see that the relationships and balance among special elements assume greater importance when the sculpture is suspended in midair. In Yoon’s work, falling to the ground is equated with fracturing or bursting. The chain reactions among abstracted entities illustrate a theme that the artist has long been exploring: the structures of sacrifice and belief.

In Seeing Things the Way We See the Moon (2013–2014), the artist stages a precarious situation. Having bound her own long hair to a high ceiling, she hangs from a metal bar placed just underneath, exposing herself to a perilous situation that could end in her being scalped. Two assistants stand on ladders on either side of her, using office scissors to cut the knot where her hair is fixed to the ceiling. Once her body is free, she lets go and drops. Finally, she steps on a hollow turtle shell at the point she falls, landing with a cracking sound amid feelings of tension. Her risky feat can only be said to have reached a point of security once the shell has been broken. In her distinctive structure of visual logic, the artist is illustrating the question: “Is it possible to justify the sacrifices that a previous sacrifice leads to?” Not only in her material sculptures but also in her performance approach, Yoon adopts fascinating creative methods based on her conceptual explorations of the sculpture medium. Additionally, her creative process has created a system where she must exert the force necessary to hold herself up, while giving her full trust to others to whom she assigns a momentous responsibility in a relationship of interdependence. Here, she seems to illustrate a belief in the power of creation as a way of objectifying risk.

Inside and Out

In the work of Jiyoung Yoon, two different horizons intersect with equal weight. One is a critical thematic stance that originates with her personal experiences and awareness and that connects with social attitudes. The other involves conceptual ideas about material that arise from her understanding and interpretation of sculpture’s visual aspects. The work that results from this shows no direct indicators of social or political incidents. At their simplest level, we see objects designed in sensory ways; at a more complex level, we find what appears to be a meta-discourse on the sculpture medium. Often, this is where the interpretation of her work stops. Indeed, the history of modern art is one in which medium-related discourse has taken place autonomously. Contemporary art in a context in which art has separately emerged as a form of social practice that is not afraid to intervene. When things exist in between or outside the two, they can often be regarded as personal or abstract. Turning attention back to Jiyoung Yoon’s work, we see how it attempts to transcend this either-or approach to art’s social nature. The personal is presented as something social rather than strictly private, and interdependent structures emerge in the seemingly autonomous.

In her process of considering the invisible structures of incidents and the relationship between their inner and outer aspects, Yoon has appropriated mold-making as a crucial element of sculpture. A single concrete scene: in 2014, an incident occurred in Korea that was tragic enough to alter the very structure of people’s minds. It was only after undergoing a painful change lasting for a few years after the Sewol ferry sinking that she was able to address a social catastrophe that seemed to overwhelm her both personally and artistically. In No Planar Figure of Sphere_Allegedly Matt (2018), Yoon shows the planar figure of a human form, together with a sculpture component of silicone skin. Like the “sphere” referred to in the title, the human form incorporated into the work is concrete rather than an abstract shape. The human form used in the work was adapted from physical data for a man named Matt, which were purchased from a Canadian 3D scanning company. In A Letter to Matt (2018), the artist explains that it is “difficult to make a planar figure of a human body, just as it is impossible to spread a sphere out due to its curves.” Nonetheless, she adds that she has “done my best to make silicone skin to place on the gallery floor.” The 3D scanning data of the body is not enough to fully grasp the human shape; realizing it as a physical sculpture is an even more impossible task. The result presented in the work is a shell without internal structure, unprepossessingly pressing against the ground.

In many industry areas, 3D graphic images are often used to show things that are not actually present or to explain things that cannot be shown in a particular place and time. The same is true with disaster reporting in the media. Even when the photographs and videos showing the ship upside-down underwater are vividly realistic, no one viewing them can truly understand the situation. During the attempts to grasp the tragic particulars of the incident as they gradually came to light, 3D simulation images began appearing in the media to analyze the process of the ship capsizing and the passengers losing their lives. In this case, abstract 3D images become metonyms for the human body. But as Yoon’s work No Planar Figure of Sphere_Allegedly Matt shows, the shapes cloaked in human bodies do not actually represent anything; they convey very little about the person behind the shell. Reduced to a shell, understanding crumbles to the ground, unable to stand on its feet. Very often, the pain evoked by real-world irrationality and overwhelming violence seems enough to make art into something very small and private. Sometimes we can only succumb to feelings of self-deprecation, helplessness, and shame, or seek comfort in fleeting moments from an insular world. Amid all this, Jiyoung Yoon stifles her screams and confronts her endless questions as she attempts with difficulty to speak out. She comments on the concealed aspects of the world, the shock that comes with their revelation, and occasions for turning subjective perceptions and lives on their head. She makes us ask why and how we are looking at certain aspects of what we are viewing.

Sculpture is the body. As seen with the minimalist sculpture of the past, abstract sculptures with the same dimensions as the body can evoke a sense of phenomenological presence in the viewer in front of them. Jiyoung Yoon has drawn both implicit and explicit comparisons between elements of sculpture and the human body. Instead of using the same cold, anonymous industrial materials as minimalist sculpture, however, she prefers working with amorphous, fleshy materials such as latex and silicone. Rather than delving into the externally visible surfaces, she seems to want to stimulate tactile sensations by imagining what exists beyond the flesh, as well as the narrative thinking that arises from that. Like physical symptoms, the sensations of the skin resemble photographic paper upon which the hidden inner workings are developed. In the Still of the Night (2019) is a spherical sculpture with a similar volume to the human body, which is designed to reveal stories inscribed on its surface as it reacts to the surrounding temperature. To see the obscured content, the viewer has to hold the sculpture close and convey the warmth of their body. As the artist explains, the viewer also has to continue withstanding the heat of their own skin. Where No Planar Figure of Sphere_Allegedly Matt used the human form as a metonym, the sculpture in works such as In the Still of the Night—which offer a more in-depth presentation of the artist’s ideas about the body—becomes a metaphor for the physical person. When sculpture metaphorically presents the body, it demands an expanded kind of reflection on that body. At the same time, the body is also a metaphor for sculpture, demanding an expanded interpretation of the sculpture medium’s visual aspects.

One of Jiyoung Yoon’s primary focuses is on the female body. In Korean society, women’s bodies are a battlefield on which the symbols associated with discrimination operate in the most extreme ways. The reemergence of feminist attitudes over the past decade or so represents a larger global phenomenon. In Korea, the #MeToo movement and other hashtag campaigns began surfacing around the culture and arts worlds in 2016. As women’s movements proliferated online, they began powering a social debate by intensively visualizing previously concealed realities of sexism. Misogynistically motivated crimes began receiving major media coverage, with repeated displays of commemoration and condolences toward the victims. Amid all this came news reports about the so-called “Nth Room” on Telegram—a case involving the production and circulation of videos showing women coerced into situations of sexual exploitation. The shockingly systematic nature of the crime and the enormity of its scale forced people to confront a structural collapse within society. More than just an issue of pornographic perspectives in which women’s bodies were sexually objectified, this was a frightening episode that alluded to the future destruction and alteration of humanity. Sensing the urgency of the situation, Jiyoung Yoon adopted an unusually straightforward figurative approach to create her work Leda and the Swan (2019). This work, a collaboration with female tattoo artists, explores the iconography from a Greek myth concerning rape by the god Zeus, while redirecting the voyeuristic perspective toward the male rather than the female. This appears to mark the time when the artist began focusing her explorations more on attitudes relating to women’s shared existential horizons.

It is not only personal misfortunes and social catastrophes that threaten to erase individuals and art. More than a given incident, it is the incident’s structural core that operates in more destructive ways. Jiyoung Yoon engages in a deeper exploration of sculpture’s inner and outer aspects as she reflects fundamentally on women’s corporeality and stands up against different forms of crisis. When individuals around the world were isolated by the COVID-19 pandemic, the artist began working to visualize a painful self-consciousness and discordance that seemed to grow in proportion to the impoverishment of physical perception and experience. Me, No (2021) is a human-sized work in which six figures with identical volumes but different shapes trade “clothes” with each other. One sculpture in the shape of a pillar with a star wears the skin of a spherical sculpture, which seems ready to split apart; the star sculpture’s skin hangs baggily over another sculpture in the shape of a pillar with a heart cross-section. The sculpture’s frameworks—their outwardly visible interiors—are presented in Vantablack, which reflects almost no light. Silicone has been used to make the exteriors: the clothing/skin is precariously draped over rigid structures that tear through them in places. The mournful beauty conveyed by the work leads the viewer to consider the misalignments between interior and exterior, the scars of separation, and the story of how these six sculptures quietly came together.

To Deliver

The visual language of art can often be subtle and poetic enough to give the sense that it refuses to present itself clearly to all. Yet this subtleness is not meant to exclude others; it is intended to implicate them more deeply and elicit emergency thinking. In a Seoul art world that has been generally urgent and exhausting over the past decade, Jiyoung Yoon has tenaciously and uncompromisingly sought her own language. At the same time, exhaustion and extinction appear to have been constant concerns. The physical properties of sculpture are such that it is fated to wear down and age, and time takes its toll on the physical capabilities a person needs to work with such heavy and demanding materials. At the everyday level, the human body’s perceptions and senses have been transforming with the spread of digital media. In the face of global ecological crisis, artists whose creation involves physical intervention must consider the ethics of ecological (non-)intervention. In a world like this, can sculpture and the contemplation of its medium survive—and if so, how? One thing is clear: The fate of sculpture as an artistic medium is not separate from the fate of existential subjects and individuals as members of social structures.

Rather than seeking a lone path of autonomy as an artist, Jiyoung Yoon has been willing to embrace the chaos of dialogue and collaboration. In one interview, she said that it is “important to me to surround myself with people whose ideas I believe in” and that “only then can I ask questions, listen, and accept.”3 During the pandemic, she co-created the 2020 work To Deliver with Stephen Kwok, a fellow artist living on the other side of the world. Amid the constraints on physical meetings, this creation captured a desperate attempt to share physical characteristics (if only) through digital space. Faced with the uneasy premonition that everything she had known and believed might disappear, she relied on the powers of friendship and solidarity to make creation and life once again possible. She had no choice but to give everything and “deliver.” The pain that we endure without escape—without even thoughts of escape—has the merciless power to turn everything into nothing. Here, Jiyoung Yoon has always sought out all things as though starting over from square one. This inevitably demands all one’s strength. It may not be clear what each of us is looking at, but vision is ubiquitous and fairly granted. What is not visible here does exist—through the choices of the sculptor.

1. Elaine Scarry, The Body in Pain, Korean trans. Mei (Paju: May Books, 2018), 10.

2. Jiyoung Yoon, The Back Stories (2023), video presentation given at Common Ground as part of the DAAD (German Academic Exchange Service) Artists-in-Berlin program. https://vimeo.com/858739023

3. Jiyoung Yoon (interviewee), Wonjae Park (interviewer), “Artist Talk | Jiyoung Yoon,” ONE AND J. Gallery YouTube, February 25, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D7m2qTO5lQM

Critic 2

Space for an Ear, a Yellow Moon1

Jinshil Lee (Art Critic)

What does it mean to be vulnerable? Vulnerability entails bodily or emotional weakness, as well as a perception and the reality shaped by struggle for survival. When discussing vulnerability, the need for cure or protection is often raised, in addition to the call for economic and medical measures that supposedly rehabilitate the vulnerable into strong and autonomous individuals, assessed mostly in terms of labor power. Meanwhile, vulnerability is classed, gendered, and racialized. Bodies that are vulnerable are not only biological but also socio-political, serving as a marker of existing inequity. Judith Butler writes: “There is no life without the conditions of life that variably sustain life, and those conditions are pervasively social”.2 At the same time, vulnerability—and, similarly, precariousness—is a quality that prompts the communal instinct in others. It serves as a stark reminder of our interdependence, which must be the basis of any political thinking.

Once the sentimental veil is removed, however, a different picture emerges. While “the political” is still venerated by some generations, it is no more than an outdated rhetoric for other generations. Words like community or solidarity have long been fossilized and crumbled down. In such times, how would it be possible for an artwork to address the communal instinct? Against the currents of cynicism and sarcasm—amidst which the ideology of self-reliance gains traction—it is difficult for an artist to insist on our interconnectedness, unless she is driven by an unusually strong faith—or even optimism—and the power to reach out to others.

Jiyoung Yoon, as far as I know, is not such an artist. None of the qualities mentioned above would characterize her, who has suffered from severe epidermal conditions from a young age and still does to this date from various auto-immune diseases. Consequently, she is acutely and constantly aware of the border and the vulnerability of her own body, sensitive to external stimuli that often cause pain. Nevertheless, Yoon often makes remarks such as “as a member of this society” or “as a woman” (albeit, to my knowledge, I have never heard her saying “as an individual artist”) when describing her work. When I met Yoon for the first time several years ago, these remarks, which would not be so remarkable under usual circumstances, came as a surprise. They sounded rather determined, which differed from how someone proclaims their status or right. (At the time, we were not discussing the Sewol Ferry incident or other catastrophes explicitly.) Her remarks were made in a way to show her determination to keep watching out for any sort of structure that caused death and suffering and to stay attentive to the ways in which Yoon herself was implicated in such a structure. Themes such as “the social” or “interconnectedness” in her sculptural work derive not from building public persona or alliance of faith but from her own vulnerability as well as her determination. Her work envisions the type of relationship among those who are vulnerable, lacking, and suffering from loss, which is formed as they warm each other up, patch each other up, and fill each other in.

Crash Landing on a Shell

One of Yoon’s works from her graduate school features a box made of yellow foam, which is put on a torso. In the photographic documentation of the work, Yoon manages to put this “vest” on with help from another and walks into what looks like a closet. There is a yellow transparent sheet set up like a screen, behind which she greets and talks to other people. Upon seeing this work, I am reminded of a squeeze machine from the film Temple Grandin (2010), which chronicles the life of animal studies scholar and autism rights activist Temple Grandin. Inspired by a squeeze chute at her aunt’s ranch in Arizona that keeps cows calm while administering vaccine shots, Grandin invents a machine that “squeezes” herself in a similar manner. In college, Grandin enters the machine and gathers herself together during an anxiety attack. Grandin, for whom physical contact with other people causes discomfort, finds comfort and security in the deep pressure administered by the machine. While she finds the machine hug acceptable, Grandin dislikes being hugged by another person.

Blowfish-Like (2013) is a video of Yoon’s performance at an art residency in Wisconsin. Yoon puts on an attire that seems like a beekeeping suit and a life vest that she designed herself, and roams around in nature. It almost looks as if she is an astronaut who landed on an alien planet plagued by an unknown virus. At one point, Yoon wipes her arm off and blows air into her vest, which then swells like a blowfish. All of these garments—including the yellow box—are displayed like lab equipment in Permeation Attempts (2013-2014). These garments, however, seem to have been made not for infiltration but for protection. Being an Asian woman with a rather small physique, Yoon faces a series of physical and psychological challenges as she lives the life of a stranger who has “infiltrated” into a foreign country. People diagnosed with autistic spectrum disorder face challenges with processing sensory information, speech communication, and social skills, and often suffer from low self-esteem. Although these cannot be compared on the same scale to the challenges faced by a non-Anglophone person of color who finds herself in a white Anglophone world, some connections can at least be drawn between them. Yoon’s early work can be characterized as an attempt to create a buffer between her vulnerable skin (ego) and those that touch it.

Seeing Things the Way We See the Moon (2013-2014) is a turning point in Yoon’s overall body of work where the subject matter shifts to the questions of trust, ethical responsibility, sacrifice, and devotion. In this work, Yoon stages and performs a structure of trust and reward where one’s safety is either at the mercy of others or ensured by their sacrifice. She is hanging by the pipe on the ceiling, to which her hair is also tied. Two people, standing on a ladder on each side, are tasked with cutting her hair off with scissors before Yoon runs out of strength in her arms. When she is able to make the fall, Yoon has to land precisely on the turtle shell laid on the floor to avoid any injury. Life, for most people, is like crash landing on someone’s hardened skin (the scutes of the turtle shell are actually made up of keratin). The work demonstrates the structure of trust as well as that of sacrifice, where the locks of hair left behind is an offering made in gratitude for the sacrificial shell.

The structure of sacrifice reappears, albeit in different variations, in A Single Leg of Moderate Speed (2015) and Alas, (2016). The former exhibition features, among other sculptures, two square frames that stand on their tip by having their wrapping stretched out to two opposing sides. There are sculptures laid flat on the floor, the combined weight of which provides the necessary tension for wires that keep other objects erect or afloat. Every piece in this exhibition, including the pair of gymnastics rings that hang from the ceiling, is connected to one another by wires and thus endures each other, in which Yoon sees an act of negotiation or making a compromise.3 Alas, is made up of a sphere with a diameter of 50 centimeters and eight spheres with a diameter of 25 centimeters, where the volume of the former is identical to that of the latter combined together. Although all nine are inflatable, they are connected in a way that letting air out of the one large sphere will inflate the other eight smaller ones and vice versa. Accompanying them is another large, empty sphere split in half, which are held together—and could thus appear wholesome at a glance—by wires that are pulling them from many sides. Staging sculptures this way seems as if the artist were suggesting a mysterious parable. However, all they are meant to illuminate is not some sort of hidden narrative but the material properties and the dynamics involved in creating and setting up these sculptures. At the same time, the material and mechanical focus of Yoon’s work alludes not only to the possibility of relations—premised on endurance and sacrifice in the web of interconnectedness—but also to the social as well as bodily affects such as anxiety, risk, and conflict.

Body as Arrangement and Function

Sculpture is tied to the body in Yoon’s work, not in their superficial similitude but in their functionality, like organisms. Although her objects— ranging from spherical, cubic, conic, and elongated to thorny—derive from the body in one way or the other, their association with the body has less to do with their shape or appearance than processual elements, such as the role of the mother mold in the casting, or certain material properties like responsiveness to the change in temperature, moisture level, tension, etc. Some of her sculptures are used to wrap other objects like skin or provide support like muscle or skeleton, while others spill out the content with which they have been filled in like digestion. Yoon’s approach to the body in her practice differs, however, from attributing human form to abstract shapes. It is rather the case where the association with the body is found in the moment of figuration that consists of gesture, motionlessness, touch, and movement, in all their interconnectedness.

Yoon’s work raises the question of what the body is. According to Butler, the individual and biological body emerges in the moment of public and political negotiation:

…could we not argue, with Bruno Latour and Isabelle Stengers, that negotiating the sphere of appearance is a biological thing to do, since there is no way of navigating an environment or procuring food without appearing bodily in the world, and there is no escape from the vulnerability and mobility that appearing in the world implies? In other words, is appearance not a necessarily morphological moment where the body appears, and not only in order to speak and act, but also to suffer and to move, to engage others bodies, to negotiate an environment on which one depends?4

The pandemic was yet another reminder of what it meant to come in contact with and engage other bodies. At the same time, it has also provided an opportunity for Yoon to reexamine the boundaries and vulnerabilities of the body in her work, which has hitherto foregrounded the structure of sacrifice and interdependence. Although the motifs of body mass and human skin have been implemented variously in That that is is that that is not is not is that it it is (2016), No Planar Figure of Sphere_ (2018), and Leda and the Swan (2019), it is in the Yellow Blues series (2021) where the use of silicone stands out the most. An oft used material for plastic surgery, silicone boasts likeness to the human skin. It is temperature sensitive and, once cured, comes to possess great elasticity and resilience. For the Young Korean Artists 2021 exhibition at the Gwacheon branch of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Yoon presented a number of sculptures in the Yellow Blues_ series where the plasticity of silicone stood out: three yellow spherical objects with varying degrees of hardness embracing one another, yellow balls in the size of a ping-pong ball that were stacked up like a pyramid, a large sphere bound so tightly by yellow ropes that its surface broke off. No longer bound by wires like in the previous work, these sculptures were placed apart from one another like an archipelago. In the corner of the exhibition space lay a cast of an arm from the elbow down, where the hand remained open as if trying to catch snow or falling leaves. A black mirror hung in the air reflected all other sculptures in silence, contributing to the almost lyric quality of the exhibition. Almost all of them were titled Yellow Blues_, which echoes Yoon’s attempt to address the state of self-consciousness—partly by referring to Agatha Christie’s Absent in the Spring—where the person chews over one’s past actions and utterances during the times of isolation prompted by the pandemic.

Yoon presents the same set of themes with a more theatrical quality in her solo exhibition at One and J. Gallery in the same year. A head swollen like a balloon, The Absent Body: A Motherless Mold and a Face(s) is laid on the floor, where the only trace of facial features in this sculpture is the peculiar shape of the ear. Yoon works consciously with the notion of body mass in this series: the six sculptures behind the dull apricot curtain, all of which are painted in black, share the same volume of 65,416 cm3 , but vary in shape, ranging from sphere, tetrahedron, cube to pentagrammic prism and heart-shaped pillar. These metal sculptures are painted with special acrylic pigment that absorbs 99.4% of the light, which creates a depthless void that eliminates a sense of volume, appearing almost two-dimension. Three-dimensionality is intimated by the silicone wrappings that have been cast from each of the six sculptures. Their wrappings, however, are swapped: The silicone “skin” of the pentagrammic prism is put like a cape on the heart-shaped pillar, and the apex of the tetrahedron has pierced the skin of the heart-shaped pillar that it is wrapped around; a sphere inside the tetrahedron wrapping seems as if it have pinnaes. Would it be plausible to claim that they are wearing other’s skin, which, by extension, alludes to a process by which to attain ideal selfhood?

The plasticity of silicone in Yoon’s work lays bare not only the border and vulnerability of the body but also their malleability and the associated feelings of hope, despair, and distress. Not only is the skin a volatile zone of pain and pleasure but it also serves as a tangent of difference, discrimination, contamination, and contempt. It is the border between self and the outside world, a psychological wrapping that gives rise to ego through the abundant sensorial correspondences it affords. Psychoanalyst Didier Anzieu writes:

The skin…is superficial and profound. It is truthful and deceptive. It regenerates, yet is always drying out. It is elastic, yet a piece of skin cut out of the whole will shrink substantially. It provokes libidinal investments that are as often narcissistic as sexual. It is the seat of well-being and seduction. It provides us with pains as well as pleasures.5

Wishing You Well

As evident in the Yellow Blues_ series where “body mass” manifests in varying geometric forms, the resemblance of the body in Yoon’s sculptures is not restricted to that of the morphological or the functional. She has expressed her wish to “express corporeality only with geometric forms,”6 where the body is abstracted in terms of volume. Volume is a geometric abstraction of space taken up by an object, and, therefore, has no form, premised on neither specificity nor identity. Such brings to mind the American minimalist sculptors who have produced cubes or other polyhedrons the size of the human body. When George Didi-Huberman examines “anthropomorphism” in Tony Smith’s Die, along with other minimalist sculptures, as a performative moment in which we are reminded of our deep-seated anthropomorphizing impulse,7 he claims that simple forms in the size of the human body often evoke an ancient monolith or sarcophagus. Such an evocation has less to do with anthropomorphism than the amorphous geometric resemblance, the silent void and the “votive quasi-portrait”8 in which we, to our own anxiety, find the resemblance to and the absence of ourselves.

Yoon’s “quasi-portraits” likewise carry semblance and absence, which allows serial emergence of beings that are anonymous yet implicated in each other, more so than the dialectics of life and death taken up by the minimalist sculptures. Her most recent work, Just One Head (2024), is a votive offering that embodies the well-wishes from her close friends who speak and write in English, Spanish, French, and Greek. Yoon records their voices onto wax cylinders with an Edison phonograph, which she then melts and recasts into her own face. The well-wishes uttered in different languages are reified and embodied. The phonographic recordings have been digitally converted before (re)casting, which emanate, almost like an echo, from the altar.

The ex-votos or votive offerings in the form of the human body have various origins, which usually lie outside the purview of the discipline of art history. According to Didi-Huberman, most of ex-votos in Medieval Europe were wax casts of either body parts afflicted by illness or prosthetics associated with such illness. While they were offered for cure or as a token of gratitude for the cure, they were also a physical manifestation of aftereffect, a relic of an ordeal. These artifacts, according to Didi-Huberman, pass from the magic of contagion so frequently invoked in religious healing—as evident in Mark 5:28, “If I just touch his clothes, I will be healed”—to the “imitative magic” that constitutes the power of resemblance. The wax is attributed with the power to extend the time of the wish, and changes when the wish changes. The wax serves multiple functions, and, with even greater plasticity than silicone, constantly reappears in new organic fixations. Wax “is charged with representing, on one hand, and warding off, on the other”, the symptom of illness. Seen in this light, wax is likened to our flesh, constantly replaced and regenerated through imitation as well as contagion.

Beeswax, along with silicone, has been the staple material in Yoon’s practice. In the Yellow Blues_ exhibition, a yellow sphere wrapped in a wire mesh hangs above a candle cube placed on a black reflective surface. The bottom of the sphere, made of beeswax, is burned and hollowed, from which the melted wax drips, collects in the empty tin box beneath it, and hardens into a candle. While the work also appears to be another allegory of sacrifice, it demonstrates, above all, the malleability and organic quality of beeswax—which issues from the bodies of bees—and therefore the workings of flesh. It represents the extension—however meager—of space and time of the wish held within the finitude of our bodies. The gesture made here is far from that of permanence or transcendence: There is always some loss when the wax melts and is recast, and the yellowness of the face, a votive offering made of beeswax, will fade over time.

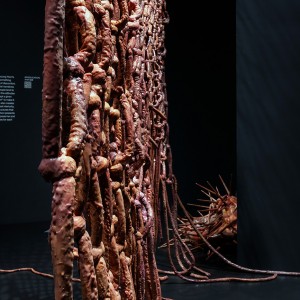

The tattered fate of our bodies and objects, which are ever-changing but ultimately finite organisms, contrasts sharply with the celebrated permanence of today’s digital media. Yoon’s sculptures present the fragility of flesh and finitude of life through the act of making sculpture, including its techniques and mechanics. Above all, her work shows the embodiment of wishes for each other’s well-being, which renders visible the public corporeality that bears the imprint of the pain and sufferings of life. The so-called “five viscera and six bowels” in East Asian medicine are not only vital internal organs of the body but they are also symbolic and indicative sites of suffering. are imprinted. The traces of pain and suffering accumulate in and are etched onto the body over time, unbeknownst to the afflicted and unlike a sudden blow, in spite of which the viscera constantly bring us back to life. “There was a time when, not knowing how to live, I took out my entrails to make a net.” (2024) is a net of prayer, a net of consecration, which the artist has spent a long time sewing, weaving, painting, and drying by hand for this exhibition. It is both an artifact of an ordeal and a portrait of a massive prayer text, tightly woven and spread out before us.

Jinshil Lee (Art Critic)

Jinshil Lee is an art critic and independent curator with an academic background in aesthetics. In 2019, she co-founded the curatorial and editorial collective Ágrafa Society, and they publish the webzine SEMINAR. She was awarded the 2019 SeMA-Hana Art Criticism Award, and authored a monograph on critical art research titled Love and Ambitions: The Time Differences of Contemporary Korean Feminist Art (2021, Mediabus). She has curated exhibitions, including Happy Time Is Good (2021, Hapjungjigu), Stranger than Paradise (2019, Boan Inn), Mirrors of Mirrors of Mirrors (2018, Hapjungjigu), and Read My Lips (co-curated, 2017, Hapjungjigu).