Hayoun Kwon

Interview

CV

Lives and works in Paris

Education

2011

with honours : Le Fresnoy – Studio national des arts contemporains, Tourcoing, France

2008

MFA(DNSEP) with special mention: Beaux-Arts Nantes Saint-Nazaire, Nantes, France

2006

BFA(DNAP) with honours : Beaux-Arts Nantes Saint-Nazaire, Nantes, France

Selected Solo Exhibition

2023

Strange Walkers, Leeum Samsung Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

2019

Then, Fly Away, DOOSAN Gallery, New York, USA

Si proche et pourtant si loin, ARARIO Gallery, Shanghai, China

2018

J’entends soudain des battements d’ailes, Galerie Sator, Paris, France

Levitation, DOOSAN Gallery, Seoul, Korea

2017

L’Oiseleuse, Palais de Tokyo, France

2016

489 Years, Le Centre d’Art de photographie de Lectoure, Lectoure, France

2015

Le Paradis Accidentel, Galerie Dohyang LEE, Paris, France

Le voyage interdit, L’École des Beaux Arts de Châteauroux, Chateauroux, France

Selected Group Exhibition

2024

Korea Artist Prize 2024, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea

2023

The Shape of Time, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, USA

Remembering/Sensing – Community of Experience, Asia Culture Center, Gwangju, Korea

Watch and Chill 3.0: Streaming Suspense, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea

NOT PAINTING, Daegu Art Museum, Daegu, Korea

Geneva International Film Festival, Geneva, Swiss

Open Systems 1: Open Worlds, Singapore Art Museum, Singapore

2022

Tribeca Film Festival, New York, USA

REPLAY THE FUTURE 8, Fondazione MAXXI, Roma, Italy

Video At Large – Intimacy, Red Brick Art Museum, Beijing, China / Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris, Paris, France

2021

XXth Attempt Towards the Potential of Magic, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea

Dear Amazon: Anthropocene 2019-2021, Videobrasil (Online)

2020

The Gold Rush, Ilmin Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

Global(e) Resistance, Centre Pompidou, Paris, France

2019

Immortality in the Cloud, Ilmin Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

Rumeurs et légendes, Musée d’Art moderne de Paris, Paris, France

The Way a Hare transforms into a Turtle, Nikolaj Kunsthal, Copenhagen, Denmark

2018

No Man’s Land, MUDAM, Luxembourg

Divided We Stand, 9th Busan Biennale, Museum of Contemporary Art Busan, Busan, Korea

Digital Promenade, Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

Respire, Herzliya Museum of Contemporary Art, Herzliya, Israel

2017

The Principle of Uncertainty, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea

Elsewhere, Pejman Foundation: Argo Factory, Teheran, Iran

2015

REAL DMZ PROJECT, Art Sonje Center, Seoul, Korea

2014

Inhabiting the World, 7th Busan Biennale, Busan, Korea

We, the Enemy – Living Under Suspicion, European Media Art Festival, Osnabrück, Germany

Inventing the Possible, Jeu de Paume, Paris, France

2013

MELTING POTES, Musée du Montparnasse, Paris, France

LOOP 2013, Les Abattoirs de Toulouse, Toulouse, France

2012

Jeune Création 2012, 104, Paris, France

2010

White Noise, Galerie Lillebonne, Nancy, France

2006

BAM!, Centre Culturel Jacques Brel, Thionville, France

A Silent Night, La Nuit Blanche, Metz, France

Eldorado, Heïdigalerie, Nantes, France

Selected Awards

2023

Geneva International Film Festival REFLET D’OR For The Best Immersive Experience, Swiss

2022

Tribeca Film Festival StoryScape Award, New York, USA

NewImages Festival Prix Spécial du Jury – LBE, France

2018

Prix Ars Electronica Award of Distinction, Austria

2017

DOOSAN Artist Award, Korea

Selected Residencies

2019

DOOSAN Residency, New York, USA

2012-2013

104 Residency, Paris, France

Selected Public Collections

National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea

Seoul Museum of Art, Korea

Centre national des arts plastiques, France

Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris, France

Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive, USA

Critic 1

If We Can Write New Poetry…

Jiyeon Kim (Art Critic)

If you believe that there are certain truths you know, they are very likely to be closer to false. People who have experienced events believe they saw everything that happened in front of them, and that they are even privy to the truths behind them. But human beings can only look in the direction they are facing. This is why so many films and novels feature stories in which a protagonist embarks on an adventure to find the truth only after being confronted with something they did not know. This familiar plot underscores how “truth” is not singular but plural.

When we are viewing an object or event, all our past experiences and knowledge are immediately marshaled. A person’s entire life is brought to bear on the place where the gaze is directed. Even when we are viewing from the same position, we cannot be said to have seen the same thing. If we stand at completely opposite sides, different memories will be left behind. Not only that, but as time passes, we will repeatedly edit and adapt things in ways that benefit ourselves, while the “truth” recedes ever further. This explains why witnesses to an event will give very different accounts of it. If two people stand at even slightly different angles, their memories after time has passed will be totally different.

Since our memories are unquestionably incomplete, we cannot avoid the pitfall of distortion. It is a mistake to regard what we saw as being the “truth,” and it is outright arrogance to believe that we understand the truth behind the world we see. Believing that we know nothing is at least a bit closer to the truth. But everyone wishes to believe they are correct, and the public prefers clear untruths over unclear truths. The misunderstandings and divisions that arise among individuals and groups begin from these misalignments. This system in relationships and history has been repeated countless times over the years.

1. The Empty Spaces Between Us

The artist Hayoun Kwon has focused on and explored these “empty spaces” that arise between the speakers and listeners in a story. The spaces examined in her work are all situated on the boundaries of truth: applicants for asylum recounting the pathways traveled in their flight across national borders (Lack of Evidence (2011)); the community of Kijong as a manufactured space created near Panmunjom for the purpose of North Korean propaganda toward the South (Model Village (2014)); the Demilitarized Zone that exists between North and South (489 Years (2016)); or the fantastical home of a woman who collects birds (The Bird Lady (2017)). Rather than presenting any judgments or conclusions, these works simply show that each person’s memories and experiences are different—and that there is no one “truth.”

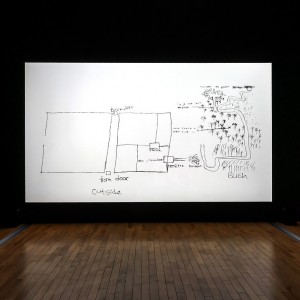

These empty spaces are particularly evident in Lack of Evidence, an animated work from 2011. The protagonist of this story is Oscar, who shares his experience while applying for asylum in France. But the French government, which has the power to make the decision, does not readily believe stories when evidence is lacking. An empty space exists between the two. Oscar draws pictures to show the route he traveled in his flight, but this does not provide “clear evidence” either.

The memory of others presents no evidence. We sometimes find ourselves wishing to look inside, but that is in the realm of impossible fantasy. In place of the medium of film—which carries the limitations of live-action photography—Kwon selected 3D animation as a medium with the magical ability to represent the memories of others as something that cannot be seen with the eyes or photographed. Imagining Oscar’s travels as she listened to his account, the artist adapted them into animation, which she juxtaposed with Oscar’s own drawings. Since even the most realistic rendering can never be the reality, various empty spaces arise among Oscar, the French government, the listener who hears Oscar’s account, and the viewer of the artist’s work. Clear truths remain eternally unknowable.

Having adopted the animation medium instead of live action for the first time in Lack of Evidence to show these empty spaces, the artist proceeded to create works in a non-live action style. Model Village, which presents a distant perspective on the Potemkin village of Kijong in North Korea, was also produced by filming an artificial model. In the process, she developed an interest in the DMZ as an intermediate space, and as she was interviewing former soldiers, she met a figure surnamed Kim who would become the protagonist of 489 Years. His account—with its descriptions of the fantastical silhouettes of never-before-seen plants revealing themselves in the moonlight, along with the sensations sparked by the life-threatening possibility of landmines and the North Korean troops appearing at any moment—was so vivid that it seemed to offer an indirect experience of entering and emerging from the DMZ.1 Kwon needed a different medium from the screen to convey these vivid senses to viewers. She thus adopted virtual reality as a way of sharing secret memories while offering a more up-close and personal experience of realistic spaces.

In The Bird Lady, Hayoun Kwon presents viewers with the new element of “time.” While the previous works had linear structures that followed a speaker’s story, The Bird Lady gives the viewer an opportunity to participate. The artist’s drawing teacher Daniel visits an old house to carry out building measurements and surveying. The home in question belongs to a “bird lady” known for collecting birds. In the work, the viewer assumes Daniel’s point-of-view, opening the heavy door and ascending the marble stairs. A woman opens the door to welcome him; behind her appears a startling scene filled with birds and cages.

Here, we see a clear difference from Kwon’s previous works. Where 489 Years had the viewer donning a VR headset and sitting down to passively view the work, the viewer in The Bird Lady moves around while wearing the headset. The tempo of the viewer’s movements is reflected in the progression of the work, as when they walk up the stairs or stop to look around. In a sense, the viewer acquires a partial ability to control time themselves. As a result, they gain a more powerful sense of presence in virtual space, venturing more deeply into someone else’s memory.

As they move their feet, stretch out their hands, and turn their heads to look around, each viewer forms a different experience. Of course, the virtual space disappears like a mirage as soon as the headset is removed—but the powerful experience of becoming someone else is engraved in the viewer’s memory as an event. Meanwhile, the layering of the slow movements of viewers wandering through virtual space in headsets creates what appears outwardly to be a performance. By incorporating the viewer’s movements as elements, the work arrives at an intermediate place that seeks to transcend the established forms of video and VR to reach the performance realm.

2. Accessing the worlds of others

Hayoun Kwon uses VR to more concretely show the layers of truth that exist between memories and experiences. She creates her works so that the viewers passing through them gain a richer perception of reality. No matter how realistically it may present things, however, a media-based work disappears the instant the lights go off. Not only that, but the dictionary definition of “imagination” refers to “taking as true what is not true or is of unclear veracity.” How are viewers able to better see reality through a virtual experience of drifting through space without having their feet planted in the real world?

Ever since the emergence of what we refer to as “media,” many philosophers have expressed concerns over their relationship with human beings. In particular, Günther Anders warned of media’s potential to take the place of actual experience and rob human beings of their critical thinking capabilities. In his view, media that came pre-edited by others were “not a means, but something already decided”; as we experience this edited “phantom version” of the world, we find it increasingly difficult to understand the actual world.2 Paul Virilio observed the hollow nature of optical media, which disappear when the light does. While they seem to realistically present a distant scene before us, it does not actually exist there. The presence of media breaks down our physical experiences and interpersonal communication.3

The common view among theorists critical of media is that media alienate human beings. Their most negative perceptions might be directed at virtual reality, a state-of-the-art optical medium presenting viewers with a new world that disappears completely the instant the device is taken away. But in contrast with television or cinema, the viewer’s body itself is implicated. Providing a one-person experience in which the viewer’s physical response is incorporated as an enemy, VR does not alienate human beings—it pulls them into the middle of the event.

In reality, our physical actions create changes as they interact with the outside world. If VR functions truly “realistically,” users acquire a sense of “psychological presence,” or the perception of being actually present somewhere else. Researchers have said that in such cases, the users’ motor nerves and cognitive systems operate similarly to the way they do in a real-world situation. After experiencing something, the body inscribes memories—which is why virtual reality may be used for various training purposes, including disaster response and driving.4 Taking advantage of this aspect, Hayoun Kwon ironically guides us to awareness of a different reality that we have not experienced. Rather than passively observing, the viewer actively enters the work and the intimate memories of another, making use of their motor nerves and cognitive systems. They soon become aware of a new truth: that different truths can exist depending on the direction from which an event is viewed.

Indeed, research has shown that using VR to experience things one ordinarily would not encounter helps to build “perspective-taking” skills, or the ability to understand other points of view, ways of thinking, and emotions.5 As the experience of viewing the work is inscribed on the body as a personal memory, it is also guiding us to transcend our own narrow, distorted perspective and access someone else’s world. Where the light reminds, a small foundation is formed for rapport and solidarity.

3. The Virtual As a Place

With her successive works 489 Years, The Bird Lady, and Peach Garden (2019), Hayoun Kwon focused on personal and private memories. Since the 2020s, she has expanded her scope once again to explore public places and histories. With Kubo, Walks the City (2021), she showed the boundary between freedom and censorship by focusing on a newspaper archive and early 20th-century landscapes in Seoul. In 2023, she presented The Forgotten War at the Asia Culture Center’s Interactive Art Lab. In it, she summoned memories of the Battle of Jipyeong-ri, which saw some of the fiercest combat in the Korean War but has been forgotten over the years.

The Battle of Jipyeong-ri is recorded in history as a victory for US forces, but as the artist examined the accounts of surviving soldiers and the archival materials preserved in France and other locations, she arrived at a different truth. The ones fighting to protect the key strategic village of Jipyeong from Chinese communist forces were American and French troops, along with a few South Korean soldiers who were included among the French forces. In her work, Kwon shows stories from the differing perspectives of war reporters and South Korean, French, and Chinese troops, guiding viewers to experience several different points of view on a single event.

The new work The Guardians of Jade Mountain (2024) is similarly based on historical stories associated with Yushan (“jade mountain”) in central Taiwan. At the time Japan invaded Taiwan, the Bunun people living on Yushan were a minority ethnic group that put up some of the strongest resistance. Obviously, the official history only recorded the conflict among states. Not only that, but Taiwan’s various minority ethnic groups had such unclearly defined cultures that even their languages have not survived today. At the time the artist first investigated the available materials, there was no way to determine whether the story of the leader of the Bunun sharing a personal friendship with visiting Japanese anthropologist Ushinosuke Mori was real or invented. Through tenacious recording, Kwon tracked down the basis behind this story and recreated it as a poetic landscape.

In a virtual space created with light, the viewer listens to the story of how Mori arrived in Taiwan as they slowly enter the area of Yushan. Holding a bamboo lantern in their hand, they follow Mori’s footsteps while wandering through the mountain’s foothills. They rely on the lantern’s glow as they discover never-before-seen animals and plants. Plants are often given academic names based on their discoverer, and there are said to be many plants in Taiwan that were discovered by and named after Mori. Hayoun Kwon investigates the reality by transporting the differing Yushan plant life inhabiting different altitudes into the realm of virtual reality, while naturally capturing the movements of animals living in this location.

The bamboo lantern may be the most interesting device here. Because the lantern in the virtual reality is synced to a real one that the viewer is holding, they viewer is able to gain a more realistic sense of walking through the darkened forest while illuminating it with their light. Owls fly off, spooked by the glow; the leaves change color in the light. Perhaps something similar happened with the scenes Mori witnessed while exploring Yushan. Through this correspondence between the viewer’s perceptions and the VR response, the viewer comes away with clearer memories and stronger sense of being actually there.

Nevertheless, VR is a medium that disappears when the power is disconnected and the light goes out. In reality, the accumulation of social memory and history causes a physical “space” to become a contextualized “place,” which can continue existing even after the actual space has disappeared. But if VR does not exist as a physical reality, can it too become a place?

The media theorist Götz Großklaus has claimed that even as the emergence of cyberspace has transformed our environment from material to non-material spaces, “place” does not disappear; according to him, concrete memories and evidence play an important part in making a place.6 Indeed, one Korean study found that when a third party’s personal memories were experienced with a strong sense of immediacy as a virtual environment, the subjective sense for the experiencer was enough to elicit different personal memories. We tend to regard the virtual spaces created by digital media as “non-places” without memories or physical evidence, but a realistic sense of place can be created through immediacy, transfer, and connection.7

As she discovers the empty spaces in reality, Hayoun Kwon studies records and oral histories to create virtual spaces that bring the memories of others back to life. Those spaces are newly organized by the experiences and memories of the viewer. As these different individual memories are juxtaposed with them, Jipyeong-ri and Yushan become “places” that clearly exist, even if they are not present in reality. The artist allows us to see what we cannot actually witness, designing an alternative world that does not exist in reality but is absolutely essential. While misunderstandings and disconnections mean that the empty spaces in reality continue to grow without being bridged, Kwon’s work serves as a light illuminating that hollow darkness.8 Through imaginary spaces, we who exist in reality are able to grow a little closer.

4. Bodies and Layers

There is also another event that occurs in this place. XXth Attempt toward the Potential of Magic (2021) includes the additional external device of a performer who moves along with the viewer. The viewer wears a VR headset as they walk through an imaginary garden illuminated by fireflies. They move slowly, sometimes walking and sometimes touching things. The performer attaches to each one, copying the viewer’s movements, so that the duet of movements appears something like a dance.

Of course, the performer’s movements are not visible to the viewer wearing the headset; the device exists for the benefit of the other viewers. The structure of the work is one in which three people enter simultaneously and take turns viewing the work. The one viewing it ahead of the others effectively gives a performance before the ones who are waiting their turn. After they finish watching and return to their place, they can observe the “performance” by the next viewer. While the positions of the viewers are changing, the real world is intersecting with the virtual reality: trained performers who are always well acquainted with the content of the work serve to mediate between the inner and outer worlds, while also becoming catalysts who more clearly show the physical and performative aspects that have been added to the world.

The idea behind this experiment was taken from Peach Garden (2020). The work provides a wider space to give the viewer more physical freedom, as the artist focuses on the image of viewers moving slowly in an otherwise empty setting. Preventing the virtual space from remaining something meaningless and empty required the bridging of the gap vis-à-vis the real-world environment; the movements of the actual, present bodies are well suited to this role. There is also something highly poetic about the viewer’s slow movements while witnessing the virtual garden area in Peach Garden with their device on and the movements of their hands touching the flowers and leaves.

Physical movements are introduced in more concrete ways in The Forgotten War. As the viewer dons their VR headset and opens their eyes in the dark, different figures can be seen performing different actions. When the viewer approaches one of those figures from behind, aligns their body’s position with them, and places their hand over the figure’s hand to follow its movements, the scene shifts and the figure’s memories are played back. This is an example of the hand tracking technology used in VR.9 At the same time, each VR viewer performs different hand motions, and other viewers who are waiting their turn are able to view another performance.

In a sense, virtual reality may be characterized as the medium with the least amount of corporeality. By using these methods to include corporeality in her work, Kwon heightens the sense of immediacy for the viewer and layers an element of performance on the exterior of her work. Having experienced the truth in different directions in and around the work, the viewer comes to see the Battle of Jipyeong-ri in a more three-dimensional light. In this way, the layers of memory and experience that the work attempts to share internally are able to expand outward. What arises is a structure of layers between individual experiences.

5. The rebirth of the “empty space”

In Hayoun Kwon’s body of work, earlier and more recent creations exist in close causal connections, with layers forming as new elements are applied to existing structures. In the past, the artist has explored the direction of the gaze and the different layers of events while discovering their “empty spaces.” She has adopted the medium of virtual reality to show intimate personal memories and expanded the scope of her work with elements of corporeality and performance. Her new work The Guardians of Jade Mountain is a reflection of all these previous characteristics that also experiments with new elements.

Discovering the empty spaces in between Japan’s invasion of Taiwan and the resistance staged by minority ethnic groups there, Kwon shows the potential for an empty space through personal stories relating to an actual figure, namely Ushinosuke Mori. She creates a concrete space by assembling Mori’s surviving records along with information on the Bunun people’s culture and actual topographical characteristics, flora, and fauna, designing a work where viewers can connect with the memories of order through an experience with a greater “you-are-there” sense. Here, too, the movements of the viewer expand into the realm of performance—a device introduced to create a more stimulating scene. The artist also places translucent curtains outside the viewing space, printed with trees and silhouette images from the forest.

This device is taken from traditional Taiwanese shadow theater. The artist also applies the motif within her work: as they accompany Mori on his explorations through the deep forests of Yushan, the viewer follows a flock of butterflies to a broad rock, which they illuminate with the bamboo lantern in their hand. Under its glow, the shadow play begins. A scene of confrontation between the Japanese and Bunun plays out metaphorically to the rhythmic sound of drums. The image of the viewer walking through the forest and observing the shadow play appears from outside the curtain to resemble Mori exploring the deep forests of Yushan.

In XXth Attempt toward the Potential of Magic, Kwon showed her idea of incorporating the viewer’s physicality into her work through the performer’s presence. Here, she uses shadow theater in a clear declaration of incorporating performance as another layer to her work. The viewer alternates between positions inside and outside the work, both observing and being observed. In between these two places vis-à-vis the artwork, a forgotten piece of history is inscribed on each individual viewer as a new memory. A single space is pervaded by collective memories and experiences with multiple layers. At this moment, locality arises in virtual space. An “empty space” is thus reborn.

6. A World Where No One Is Alienated

While a great deal of research and meticulous technical planning go into Hayoun Kwon’s creation of her virtual reality-based work, the scenes that the viewers experience inside are simple and metaphorical. The artist does not go out of her way to provide annotations or concrete explanations. Her attitude is that the image one is beholding represents another truth. The real world consists of many different metaphors, and new truth emerges as those are understood and connected. All we can do is walk through the work and discover worlds that did not exist before.

In the face of technology and media, our reality is one in which human beings are constantly alienated. Anders had something of a point when he expressed concerns that media might take the place of our actual experience and erode our critical thinking capabilities. When an artist engages in critical thinking and expresses it through a particular medium, what arrives before us is but one opinion. Rather than speaking herself, Hayoun Kwon has the figures in her theater speak for themselves. This is an example of the poet’s mimesis as described by Aristotle. Presented with a metaphorical situation instead of a story with a defined perspective or moral, the viewer immerses themselves in the experience of another, and the key to judgment is placed in their hand. The image of a viewer who does not appear alienated in the face of the medium may represent a rebuttal to Anders’s pessimistic view seeing us as nothing more than “components” of technology.

As they break down the boundaries between virtual reality and performance, Hayoun Kwon’s works incorporate bodies—the most analog presences there are—into creations that employ state-of-the-art technology. Seeing her work’s use of a different form of language, I found myself thinking of the “new poetry” approach (sinchesi in Korean).10 When we are using the same medium, is it possible to see in it utterly new possibilities? When the virtual simply incorporates real-world spaces and single perspectives, it is nothing more than an imitation of life—but a place where memory and experience overlap can become an alternative reality even in virtual form. The stories that stand out here are the ones not visible in reality. The “light of enlightenment,”11 cast by one subject upon the objects outside, loses all meaning. This place illuminated by individual beings, each bearing their own possibilities, is a world where no one is alienated.

As the truth blossoms in each empty space and the viewers’ movements are layered together, the result is a rhythm in itself. Seemingly rigid contexts of memory and experience break apart, and the layers—and spaces in between the layers—surge in richer ways. What we had believed ourselves to know is proven false. All that we can know is that we are still unaware of the truth before us. If the visible is all as Vilém Flusser suggests, then here is where we must start again. A poet once said that while poetry is read with the eyes, we read and re-read it while breathing with the body.12 If we are able to write new poetry through the work of Hayoun Kwon, perhaps it will be poetry that is read and re-read with our whole body.

1. National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, “Conversation with the Artist” (Hayoun Kwon, exhibition curator Maeng Jiyeoung, and performance studies scholar Son Okju, February 25, 2021)

2. Sim Hyeryeon, Media Philosophy of the 20th Century (Seoul: Grinbi, 2021), pp. 109–111.

3. Paul Virilio, Korean trans. Lee Jeongha, Art as Far as the Eye Can See (Paju: Youlhwadang, 2008), p. 27.

4. Jeremy Bailenson, Korean trans. Baek Woojin, Experience on Demand (Seoul: Dong Asia, 2019), pp. 34–57.

5. Jeremy Bailenson, pp. 122–139.

6. Sim Hyeryeon, pp. 312–321.

7. Lee Hwayeong, Kim Sangyong, “Subjectivation Study for Immersing the User into the Perspective of Personal Space Represented in a VR Environment Display,” Journal of Digital Contents Society, Vol. 25, No. 1, 2024, pp. 39–48.

8. Vilém Flusser, Korean trans. Kim Seoungjae, In Praise of Superficiality (Seoul: Communication Books, 2006), p. 304.

9. This technology operates a computer based on detection of a user’s hand movements. As viewers of The Forgotten War follow the hand movements of the figures they meet in the virtual space while wearing their VR headset, these motions are detected and the images and sounds are transformed.

10. This genre of poetry departs from established styles, taking on a form that is like a “new body” (sinche in Korean).

11. Vilém Flusser, p. 363.

12. Hwang Inchan, A Person Briefly, Quietly Confessing (Paju: Nanda, 2024), pp. 32–40.

Critic 2

Intimate, Personal, and Episodic “Testimony” as a Potentia for the Construction of History

Juhyun Cho (Independent Curator/Adjunct Professor, Yonsei University)

What is important and what is not? Since there is no way of knowing (and we would never think to put such a simple, silly question to ourselves), we accept as important whatever others do, for example an employer whose questionnaire we fill out: date of birth, parents’ occupations, schooling, career history, domicile (and, in my home country, membership in the Communist Party), marriages, divorces, births of children, successes, failures… It is terrible, but it is a fact: we have learned to see our own lives through the eyes of administrative questionnaires or police reports.

–Milan Kundera, Immortality1

I. Introduction

In her artistic work, Hayoun Kwon has explored the ambivalent relationship between reality and imagination, focusing chiefly on the themes of boundaries and identity as she reconfigures personal histories and memories. As a medium to express these themes, she focuses on the basic communication method of the story, while using devices such as 3D animation, documentary elements, and virtual reality to show how people speak and relate to others in new media environments. Blending the genres of documentary and imagination, Kwon shows the imaginary and fictional nature of the geographical and political boundaries that exist in military border regions such as Korea’s Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) and along national borders in general. Here, episodes rooted in the personal experiences of people whom she has encountered serve as key mechanisms for redefining the truth.

In his Poetics, Aristotle writes, “A whole is that which has a beginning, a middle, and an end. (…) Of all plots and actions the episodic are the worst. I call a plot ‘episodic’ in which the episodes or acts succeed one another without probable or necessary sequence.”2 In his conception, these episodes exist outside the causal connections of the plot, amounting to silly coincidences that could safely be omitted from the overall composition—unimpressive events that leave no mark on the characters’ lives. Yet our actual lives consist of innumerable episodes.

For the exhibition Korea Artist Prize 2024, Hayoun Kwon presents the four works Lack of Evidence (2011), Model Village (2014), 489 Years (2016), and The Guardians of Jade Mountain (2024). These works focus on the relativity of episodes, where the causal connections that exist within individuals’ memories and experiences are capable of surfacing suddenly one day to generate various results—arising along one of the countless boundaries that define imperialism, identity, ideology, the state, the nation, non-human beings, indigenous peoples, and colonial history. An episode is like a landmine, a potentia capable of constructing a historical incident. Most of these mines never detonate—but the most unassuming of them could eventually resurface to deliver a devastating blow. All events, no matter how trivial, become the causes behind later events, harboring the potential to transform into stories and histories in the process.

During a conversation with her Japanese roommate while she was studying at the Beaux-Arts Nantes Saint-Nazaire in France, Hayoun Kwon found herself experiencing curious feelings relating to history. Based on her own experience of a Korean educational program that emphasized the colonial history of Japan’s occupation of the peninsula, she was shocked at the historical knowledge of her Japanese friend, who had not been taught much about Japan’s imperialist history. Soon, Kwon began interviewing Japanese students for a documentary work on differences in historical interpretations between Korea and Japan. In the process, she unexpectedly received an apology from a Japanese friend who had learned about imperial Japan’s history of colonialism and asked for forgiveness over the misdeeds their country had committed. This led Kwon to pose the question of how “historical truths” are established for those (descendants) who do not possess related personal experiences or memories.

Continuing under this critical approach, Kwon conceived a 2010 documentary work that was set against the backdrop of the Seodaemun Prison History Hall in Seoul. She believed in the potential for a documentary video to capture the truths remembered by that space. Yet the place she found was filled with tourist spectacles and historical exhibitions oriented toward peripheral stimulation. Soon, she came to see that she had not been given the opportunity to reflect critically on the facts, legitimacy, and truths hidden behind history. Even the suffering endured by individuals was objectified into something like a hidden-camera spectacle; historical incidents were abstracted into simple images. Photographs of independence activists being subjected to horrific tortures and installations recreating the various settings from the period were enough to trigger immediate sensations of compassion and pity, but they also elicited a sense of “better them than me” relief, an irresponsible feeling of not being implicated in that suffering, and a perception of being effectively helpless to do anything about it.

Kwon’s documentary video The Wall (2010) was ultimately left unfinished. So how might it be possible to demonstrate past events and memories that were deliberately erased or omitted or otherwise unrecorded? Could the historical sufferings of people concealed in the debris of history be rescued by imbuing subjectivity into objects and places repudiated or represented within “witness theory” as it has existed to date? If so, what ensures that a witness is acknowledged as a witness? What standards for witnesses are recognized in courtrooms, in laboratories, and in the media?

II. “Testimony” As a Relational Process

Around this time, Hayoun Kwon developed an interest in the immigrant identity and the concept of national boundaries as she began visiting the immigration office to earn permission to stay in France after completing her studies. For those applying for asylum in a foreign country after risking their lives to cross the border, the national boundary operates as a standard distinguishing between “us” and “them” or “human” and “not human.” In the artist’s conception, these borders were “humanmade products of perfect fiction,” as well as imaginary spaces that could be reconfigured at any time. Lack of Evidence (2011) is an early work reflecting her concept of borders. This video adopts a documentary animation format to tell the story of “Oscar” (not his real name), a Nigerian who applied for asylum in France but was turned down due to a lack of “objective” evidence. In this work, she explores the different possibilities for narrative structures to “rescue” the episodic personal memories of an African person, which are not recognized as evidence within a larger fictional narrative created by the “situational knowledge” of white Western middle-class male intellectuals.

The video begins with narration by a middle-aged woman speaking French, as 3D-animated images show a quiet rural Nigerian village shrouded in deep darkness, resembling a scene from a children’s story or folktale. The woman is an interpreter who assisted Oscar with his exile application process in France. She shares background information about the events of a particular day when Oscar’s brothers attempted to flee their village. The lens of a virtual camera enters Oscar’s home to examine its interior, as the video shows the structure of the 3D graphics used to create those images, and the narration switches from the woman’s perspective to that of Oscar himself. Oscar’s brothers learn from their stepmother that their father intends to kill them. Hearing the sound of strangers pounding on their door, they jump out the window and flee through their backyard into the village’s forest. At the moment they begin their escape, the video switches to black-and-white line drawings instead of realistic 3D animation graphics—showing the impossibility of knowing how much of this memory is true and how much is fictional.

As they follow behind him, Oscar’s twin brothers are shot dead by their father’s men, and Oscar alone manages a narrow escape. He has applied for political asylum in France because he feels he cannot return to his home country of Nigeria. As a priest and sorcerer in charge of the village’s rites, the father was unable to accept the brothers because he felt obliged to follow the longstanding cultural and religious beliefs and traditions of a Nigerian tribal community that regarded twins as a malign presence. The only pieces of evidence that Oscar is able to present to the French government for his asylum application are a French translation of his oral account and a pencil-drawn map of the village that he produced to explain the process of his escape. It is only when these standard paper-sized pieces of physical evidence appear that the video switches to live-action photography rather than digital animation.

Lack of Evidence questions the standards applied by national authorities in singling out certain events as “important” in historical and administrative terms. The perspective of the administrative questionnaire or police report has transformed into a consummate tool of power, which has been used to shape modern Western systems. In contrast, personal and subjective memories are not recognized as evidence in the world of the victors. The memories recalled by a Nigerian whose life is endangered by the beliefs and religious and political influence of an African tribal community amount to invalid testimony in a European state; the suffering and fear of “others” have been concealed throughout modern history. For her work, the artist combines animation that betrays its own artificiality with live-action photography that captures the given environment. Her approach transcends the conventional documentary’s epistemological assumptions as the voice of the French-speaking interpreter alternates between an African person’s episodic accounts and the ambiguous facts of his case. Through this new documentary methodology, the artist is “not showing the truth of the events, but merely revealing the ideologies and perceptions that construct competing truths—the fictional larger narratives that we rely upon to understand incidents.”3

How have these “fictional larger narratives” been constructed and bolstered to date? The modern account of history whose meaning is recognized within the timeframe of progress is one conceived in accordance with a causal narrative structure. To support this, the most important scientific and legal consideration for testimony is that of “simulated neutrality,” which serves as a foundation for the modern institutions carried over from the Enlightenment. Institutionally recognized testimony must be absolutely objective, without reflecting a person’s subjective thoughts or feelings. The witness capable of giving a realistic explanation that serves as a mirror of the truth “must be invisible, that is, an inhabitant of the potent ‘unmarked category,’ which is constructed by the extraordinary conventions of self-invisibility.”4 Ironically, the affected in-visibility of this “modest witness”—concealing any racial, class-based, or gender indicators as though transcending all interests—has come to guarantee the objectivity of scientific knowledge and a unitary concept of subjecthood that is “modern, European, and male.” In this way, science has firmly established itself as an authoritarian means of understanding the world. The world has come to specifically view the “situational knowledge” of white Western middle-class male intellectuals as something transcendent, comprehensive, and objective.5

Due to the abundance of visible indicators, the situational knowledge that Oscar relates as a person of color to the French government officials—elements such as the traditional beliefs, practices, and religious rites of certain tribes in Nigeria—can never be recognized as objective truth, and his testimony is thus not something that can be acknowledged. It is regarded simply as a dehumanized incident, which from the perspective of white Western middle-class intellectual males must be “interpreted” by someone. In a setting to determine the legitimacy of someone’s application for asylum across national boundaries, it is a storyteller’s tale of adventure, where there appears to be no basis for according it the status of “testimony” or an “eyewitness” and for affirming its veracity as an event, or for declaring what is important in elevating the events to the realm of what is right. Through her use of 3D animation, Hayoun Kwon has created a relational process in Lack of Evidence that is not about finding testimony in the presentation of the witness or the acts or objects of witnessing, but about ushering into the conversation certain alienated, excluded groups of human beings and the practices associated with them.

III. Contradictory Spaces Where the Real and Imaginary Are Unbounded: Shared Spaces Mediated Through Episodes

Hayoun Kwon’s interest in the national border as a sociopolitical, cultural, and psychological boundary has been consistently directed toward the DMZ, which represents the military border region between North and South Korea. The DMZ is effectively off limits to human beings, with all access restricted for anyone who is not performing military patrol duties. For several years, the artist requested permission to film a documentary work on the civilian village of Kijong, which was artificially created in the DMZ by North Korea for purposes of regime propaganda. Her requests were ultimately denied, and she decided to create her own architectural model of the propaganda village for use in a digital video. She created Model Village (2014), for which buildings made of transparent plastic were assembled on a white-painted terrain base. Inside the model, a virtual camera moves around, accompanied by various sounds and powerful illumination that adjusts light and shadow. Through this staging, the work dramatically visualizes the theatrical nature of the setting.

Taking in the image of a model village where no one can visit or live, the virtual camera moves inside as the voice of an actual foreign tour guide is heard. Within the village, conversations among people provide a representation of life in North Korea, accompanied by broadcasts that praise the Kim Il-sung regime. The fictional nature of the place is further heightened as the frame shows devices that lay bare the artificiality of the recreation. With artificial lighting covering the whole village and projecting shadows of it onto a graphically realized mountain, the work alludes to the nature of collective memory of the DMZ’s geopolitical setting as something originating in psychological boundaries that are irreducible to visual evidence alone.

Where Model Village (2014) examines the physical relationship to an empty object from a distant perspective looking over a border, the work 489 Years (2015) uses its fantastical 3D animation depiction of the DMZ landscape to imaginatively represent the actual experience of a speaker who worked there as a search team member. 489 Years takes the viewer inside a DMZ recreation based on what the artist imagined after hearing a personal account of the memories of a soldier who worked there as part of a search team. A “virtual space” within reality that is off limits to everyone, the DMZ is rendered here in 3D animation, where the virtual reality offers a vivid experience of fictionally crossing a real-world boundary. The virtual reality medium is a tool that focuses attention on the fleeting nature of human existence by allowing for a physical experience among images. As they enter a contradictory space where the wall between the real and virtual has dissolved, viewers gain the ability to insert themselves into the story through their own reflections. In this way, the artist uses a particular individual’s personal memories and episodes as a medium to create a space shared between the speaker and listener.

As the brain finds itself activated by this person’s stories, gestures, and certain scents and tastes, the episodes stimulate its flows of memory, leading it to imagine things and create conflicting narratives. The DMZ-related memories narrated by Mr. Kim in 489 Years include an anecdote about “hearing the sound of a landmine triggered by a roe deer, leading a KP colleague to go out with a saucepan to look for the injured animal”; “remembering how beautiful the DMZ landscape seemed as I looked out at it from a checkpoint while taking an early morning whiz”; and “putting a rock in a barbed-wire fence and then checking it during the next search to see if any enemy had passed by.” Here, the individual’s episodes form a relationship that includes not only the speaker but also the listeners, causing them to sense their shared responsibility as witnesses to these events.

The fluid, uncertain nature of episodes that even in the moments of their telling are constantly being reconfigured within this relationship among people serves to restore the exchange capabilities of community experience—an aspect of the oral culture that disappeared with advancements in print media. The source of the story medium lies in “experiences conveyed from one mouth to another.”6 The teller integrates things heard in “distant settings” from a “distant past” into their own tale, before going on to create another experience for the listeners. In the oral tradition, the recitation of myths, folktales, and heroic stories led naturally to their recreation and adaptation in the process of them being shared with others. That potential for different variations of the same legend or story to arise vanished from the communicative approaches of the modern era, including the stories and information conveyed through print media. This offers evidence of the “decline in the possibility of conveying experience”7 that has occurred in modern times.

In the environment of the 3D animation medium, Hayoun Kwon discovers a new possibility for storytelling. In contrast with live-action film’s faithful capturing of a given environment, 3D animation creates openings for the artist, the viewer, or anyone else to overwrite a new story on the other’s narrative from their own subjective viewpoint. The title 489 Years refers to the estimated time needed to remove over one million landmines from the site. At the end of the video, the man voices his hope for the DMZ to disappear, and the frontlines transform into a sea of fire. It is a dramatic moment that is utterly impossible in the real world, where the border dissolves in a gradual, nostalgic way. This moment shows the DMZ to be an imaginary, contradictory place where flowers (beauty) coexist with landmines (danger). By “situating reality/fantasy and fact/fiction upon the same horizon and constructing a circuit of mutual exchange,” Hayoun Kwon’s three-dimensional virtual space becomes a shared setting “where questions can be raised from various angles over the voices of the witnesses attesting to their memories along the borderlines.”8

IV. “Shadow Play Attesting” To a Magical Friendship

Still harboring disappointment over The Wall (2010), her unfinished documentary work on Korean and Japanese history that she conceived while studying in France, Kwon traveled in 2021 to Taiwan—which shared Korea’s experience of Japanese colonization—to resume her research into modern East Asian history. At the time, the COVID-19 pandemic was raging, and her research in Taiwan proved a difficult process with many stops and starts. Most of her activities involved meeting with other people. She described the experience as one of realizing that there are “ultimately only subjective perspectives in this world,” and that no matter how objective a view we strive to take, what remains in our memory “is not a line from a history book but a word spoken by someone beside us.”9

During this turbulent period of ongoing isolation, the artist pored through the scattered records of Japan’s occupation of Taiwan during the early 20th century. Her attention fell on an episode recording the special friendship that arose between Ushinosuke Mori (1877–1926), a Japanese cultural anthropologist who studied the indigenous cultures of the island’s minority ethnic groups, and Chief Aliman of the highland Bunun clan. The story amounts to an oral tradition rather than a part of the historical record, but Kwon used the research materials left by the Taiwanese-based anthropologist Mori—including photographs, maps, and notes—to create the open narrative structure of a documentary and 3D animation work. She devised The Guardians of Jade Mountain (2024) with a virtual reality interface to allow viewers to immerse themselves in personal stories from history and a village where highland peoples in Taiwan lived during the early 20th century.

The video observes a farewell speech given to colleagues by Mori as he returns to Japan, 18 years after he arrived in 1895 as an 18-year-old army interpreter in Taiwan, where he would go on to conduct research on its indigenous population. An adventurous land surveyor, Mori would develop deep friendships with indigenous people in Taiwan, mastering the languages of several tribes over the course of his earnest exchanges and publishing five books on those languages. For these activities, he has been lauded as a pioneer in research on indigenous Taiwanese residents. Assembling vast amounts of information in the areas of anthropology, history, folklore, archeology, botany, and geography, he created a museum collection and completed a two-volume Chronicle of Taiwan’s Indigenous Peoples. In the face of imperial Japan’s repressive policies against those residents, he argued the need to preserve their unique identity. His extensive local studies earned him a reputation as a Taiwanese naturalist during the early years of the occupation, and he became the first person to summit and collect plant sables from Yushan (Jade Mountain), the highest and broadest wilderness in Northeast Asia and a site where virgin forest and various plant and animal species had been preserved. As a result of these activities, samples of over 20 different Taiwanese highland plant species named after Mori have been entered into the botanical record.

As viewers don their headsets and enter the virtual reality, they follow the movements of a virtual camera taking in an aerial view of an indigenous village on a 3D-animated map of the island of Taiwan. Upon a tripod that rises like a tower at the island’s center is a large camera of the kind used by anthropologists in the early 20th century. The viewer travels to different villages, adopting Mori’s perspective as they take black-and-white photographs of the activities of indigenous residents. In the virtual reality narrative, the viewer walks through actual spaces and encounters records of indigenous Taiwanese residents, at which point they enter the communities of the people in question. As Mori’s camera points toward the village of the highland Bunun people, a history is provided for the indigenous people’s campaign of resistance against Japan and its new five-year ruling policy. From there, the setting shifts to the beautiful, wild landscape of Yushan, lit fantastically by fireflies. The viewer holds a bamboo lantern as they are guided into Mori’s narrative along a forested mountain trail by pangolins, squirrels, owls, and butterflies. Mori relates a story from a weeklong survey of Yushan by his large geographical research team. It tells of how his life was threatened when he was chased for five days by the Bunun tribe’s Chief Aliman, who sought an opportunity to take revenge on the Japanese for the deaths of family members who had been falsely accused by them and killed.

Through the virtual reality interface in The Guardians of Jade Mountain, viewers carry along their bamboo lantern until they come to a rock face in the mountain. As they hold their arms out to shine the light, a shadow play presents Mori’s tale of adventure, historical facts, and episodes involving Chief Aliman. Depicted in jointed cut-out shapes, the shadowed figures reenact tense scenes of Japanese soldiers storming into the indigenous people’s regions with the Rising Sun flag to the sounds of gunfire; indigenous residents fighting back with bows and arrows, only to be shot down; and Mori exploring Yushan’s plant life as he conceals himself in the forest against an endless stream of arrows fired by Chief Aliman. Kwon’s work visits the boundaries between reality and fiction, where the viewer cannot tell if they are witnessing a true story, an invention, or a fantasy. Mediated by shadow theater—an ancient storytelling technique boasting a long tradition in Southeast Asia—it accesses the spiritual world of indigenous culture and nature.

The shadow theater that Kwon applies to virtual reality has historically been used mainly by storytellers as a means of dramatically representing historical tales that are partly true and partly fictional, as well as a tool in sacred village performances to relate epic poems, stories from Hindu mythology, and other legends. In The Guardians of Jade Mountain, the shadow play magically transforms the Yushan rocks that observed these tales into a stage attesting to the people’s stories as the viewer shines them with the light of their lantern. On the unfamiliar trails of the VR-rendered Yushan, the lantern-holding viewer is guided by creatures such as pangolins, squirrels, owls, butterflies, and fireflies, along with various plants that bear Mori’s name. These presences guide the narrative, as though conspiring to share things that are not recorded in the writings of the human world. In his farewell address, Mori explains that even as his life was threatened, he never took up arms, devoting all his energies to walking around night and day to complete his explorations—and that his courage was recognized by Chief Aliman, who became a true friend. The shadow play documents the magical friendship as the figures who once held guns, swords, and bows lay down their weapons to clasp hands and embrace one another in a circle.

In this work, Hayoun Kwon explores the idea of the “enemy” by means of the history of colonization in East Asia during Japan’s imperial era. Just as her previous work focused on the relativity of episodes that reconfigured the truth as they treated the concepts of boundaries (including national borders like the DMZ) as fictional and imaginary, the idea of the “enemy” in historical narratives is something that can be newly defined at a personal level rather than a national one. In contrast with other species, human beings have thrived through sociability, a collaborative form of communication. Another aspect of this sociability is that when a group we care for appears to be threatened by another group, there is a universal tendency to dehumanize the other (group). This aspect also explains why we tend to disregard the basic human rights of people who do not belong to our own group. The extreme forms of dehumanization committed by white supremacists elicit a reaction at a different extreme. This dynamic of one extreme triggering another is not a phenomenon exclusive to any one political movement, cultural sphere, or era. From the Chinese Cultural Revolution to post-WWII Stalinism, anarchist terror attacks, the French Revolution, and Japanese imperialism, those in power have wielded dehumanization and the accompanying violence in various governmental forms.

Yet numerous examples from human history have shown that the human nature of dehumanizing other groups can be cured through collective action. While the Holocaust was taking place around the outbreak of World War II, thousands of people in Europe risked their lives to rescue Jews from persecution and death. Those who were discovered faced torture, expulsion, and even their own death and the massacre of their family members. Even so, they were willing to conceal these endangered Jewish people in their barns, attics, and other locations. What led these people to help Jews at the risk of their own lives, when so many others were either siding with the Nazis or looking the other way? Based on his analysis of eyewitness accounts from Europeans who rescued Jews during this era, sociologists Samuel P. Oliner and Pearl M. Oliner found one common characteristic among them: they had all been close with a Jewish neighbor, friend, or coworker before the war. They had no other common characteristics in terms of gender, education, political affiliation, wealth, or profession—what enabled them to take those risks was the fact that they had been or were still close friends with a Jewish person.10 In her explorations of the “enemy” concept dating back to her time studying abroad, Hayoun Kwon discovered it to be a fluid and uncertain “product of imagination,” with borders that could be broken down less by matters of nation, ideology, tradition, and religious beliefs than by experiences of friendship and contact at a personal level.

V. Conclusion

It is common knowledge that human history has evolved in ways that have transformed human consciousness and perceptions based on different codes created by the representative media of each era. The early technology of the written word and printing was a key medium underpinning the modern self, establishing an exemplar of modernity as a matter of creating order through repression. In the era that has become known as the “Anthropocene,” we have experienced the rewriting of history at the planetary scope. The episodic aspects of the narrative structures in the aforementioned 3D-animated works by Hayoun Kwon—Lack of Evidence (2011), Model Village (2014), 489 Years (2016), and The Guardians of Jade Mountain (2024)—illustrate how history achieves new stylization within a contemporary concept in opposition to modernity, and how historical, ethnic, and cultural identity is written in an era of deepening encounters among different cultures, religions, and languages. These methods of rewriting “do not create any hegemony; they reevaluate regions and areas, re-manifesting concealed maps and forgotten histories.”11

Using episodic narratives as a potentia for the constructing of history, Hayoun Kwon creates spaces shared between the speaker and listener, using virtual technology in ways that allow the viewer to fully experience and respond to another’s body amid the images. The relativity of the episodes in works such as Lack of Evidence or The Guardians of Jade Mountain shows that the standards used to select the events we deem “important” must come from very intimate, personal, and unique subjective perspectives—leaving behind the attitudes of others and the perspectives of “administrative questionnaires and police reports.” This may be presented as a new method of historical narration in the contemporary era, creating the possibility for us to break away from the modern method of writing historical writing and its linear perception of time—where only the stories of the winners and the images of the powerful survive—and to allow all of us to rewrite the history to date as living subjects.

Ultimately, Kwon’s 3D-animated works mediate the unclear, murky memories that arise in the process of sharing experiences in encounters with others. Memories are something unique to a specific person; in Kwon’s perspective, they are akin to the bluebird of the fairytale, which appears and disappears without our knowing why. We all dream of capturing the bluebird, but few of us can achieve it. Memory is something that flits onto the back of our hand at unexpected moments, only to fly off again to parts unknown. Another person’s life experiences and other incidents from the past can easily be forgotten in the collective memory. But like the bird that comes when beckoned by its trainer, past moments from life can appear before us in raw, unvarnished form through our attempts to breathe in the air exhaled by another. The narratives of imagination and contradiction shared by Hayoun Kwon aspire to the possibilities of transforming the unclear memories of life that we summon through our gestures in our relationships with others—allowing in the process for an ongoing “rewriting” of history.