Gala Porras-Kim

Gala Porras-Kim lives and works in Los Angeles and London. Her work is about the social and political contexts that influence how intangible things, such as sounds, language and history, have been framed through the fields of linguistics, history and conservation. The work considers the way institutions shape inherited codes and forms and conversely, how objects can shape the contexts in which they are placed. She has had solo exhibitions at MUAC, Kadist, Amant Foundation, Gasworks, and CAMSTL and has been included in the Whitney Biennial and Ural Industrial Biennial (2019), and Gwangju and Sao Paulo Biennales (2021) Jeju and Liverpool Biennial (2022-2023). She was a Fellow at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University (2019) and the artist-in-residence at the Getty Research Institute (2020-2022), and she is a Senior Critic at Yale sculpture department.

Interview

CV

Education

2012

MA, Latin American Studies, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA

2009

MFA, Art, California Institute of the Arts, Valencia, CA, USA

2007

BA, Art and Latin American Studies, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Selected Solo Exhibitions

2023

National Treasures, Leeum Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

MAO, Torino, IT

The Weight of a Patina of Time, Fowler Museum at UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Vistas Más Allá de la Tumba, Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporáneo (CAAC), Sevilla, Spain

Entre Lapsos de Historias, Museo Universitario de Arte Contemporaneo (MUAC), CDMX, Mexico

2022

Correspondences towards the Living Object, Contemporary Art Museum (CAMSTL), St Louis, MO, USA

Precipitation for an Arid Landscape, Johnson-Kulukundis Gallery, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA

Out of an Instance of Expiration Comes a Perennial Showing, Gasworks, London, UK

2021

Precipitation for an Arid Landscape, Amant/Kadist, New Y ork, NY , USA

A Terminal Escape from the Place that Binds Us, Commonwealth and Council, Los Angeles, CA, USA

2019

Open House: Gala Porras-Kim, Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA), Los Angeles, CA, USA

Trials in Ancient Technology, Headlands Center for the Arts, Headlands, CA, USA

An Index and its Histories, Commonwealth & Council, Los Angeles, CA, USA

An Index and its Settings, LABOR, CDMX, Mexico

For Prospective Rock/Artifact Projection, Commonwealth & Council, Los Angeles, CA, USA

The Mute Object and Ancient Stories of Today, Commonwealth & Council, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Whistling and Language Transfiguration, Commonwealth & Council, Los Angeles, CA, USA

I Want to Prepare to Learn Something I Don’t Know, Commonwealth & Council, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Selected Group Exhibitions

2023

CalArts feminist Archive, Redcat, Los Angeles, CA, USA

uMoya: The Sacred Return of Lost Things, Liverpool Biennial, UK

Chosen Memories: …from the Patricia Phelps de Cisneros Gift and Beyond, MoMA, NY , USA

A Speculative Impulse: Art Transgressing the Archive, Wallach Art Gallery at Columbia University, NY , USA

2022

Flowing Moon, Embracing Land, 3rd Jeju Biennial, Jeju, Korea

Museum of Civilizations’ Two Methodological Entrances, Museo della Civilita, Rome, IT

Schindler House 100 Years in the Making, Mak Center, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Frequencies of Tradition, Kadist, San Francisco, CA, USA

2021

Faz escuro mas eu canto, 34th São Paulo Biennial, São Paulo, Brazil

Minds Rising, Spirits Tuning, 13th Gwangju Biennale, Gwangju, Korea

Grain of a Hand: Drawings with Graphite, Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, IL, USA

NOT I: Throwing Voices (1500 BCE–2020 CE), Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Portals, NEON, Athens, Greece

2020

Out of Place: A Feminist Look at the

Collection, Brooklyn Museum, NY , USA

2019

Nowhere Better Than This Place, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Direct Message: Art, Language and Power, MCA, Chicago, IL, USA

Immortality, Ural Industrial Biennial, Y ekaterinburg, Russia

Whitney Biennial, Whitney Museum of American Art, New Y ork, NY , USA

Future Generation Art Prize shortlist exhibition, Kyiv, Ukraine

An Opera for Animals, Para Site, Hong Kong/Rockbund Museum, Shanghai, China

Lost and Found: Imagining New Worlds, Institute of Contemporary Art, Singapore

2018

Talking to Action: Art, Pedagogy, and Activism in the Americas, SAIC, Chicago, IL, USA

Second Sight, Bowdoin College Museum of Art, MN, USA

2017

Working for the Future Past, Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

A Universal History of Infamy, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA, USA

2016

Journal d’un Travailleur Métèque du Futur, FRAC Pays de la Loire, France

Aún, 44th Salón Nacional de Artistas, Pereira Museum of Art, Pereira, Colombia

Made in L.A. 2016: a, the, though, only, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, CA, USA

2014

Acciones Territoriales, ExTeresa Arte Actual, CDMX, Mexico

Fellowships/Residencies

2022

Museo delle Civilita, Research Fellowship, Rome, IT

2020–22

Artist in Residence, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, CA, USA

2021

Delfina Foundation, London UK

2019–20

Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Studies fellowship, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA

La Tallera, Cuernavaca, Mexico

Beta Local, The Harbor, San Juan, Puerto Rico

2018

Headlands Center for the Arts, Headlands, CA, USA

2016

30th Ateliers internationaux residency FRAC Pays de la Loire, France

Careyes Foundation residency, Careyes, Mexico

Casa Wabi, Oaxaca, Mexico

2015

Triangle France residency, Marseille, FR

2010

Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, ME, USA

Awards

2021–25

Metro Commission Wilshire/Westwood Station main entrance, USA

2019

Art Matters Foundation, USA

Thomas Sillman Vanguard Award, USA

Future Generation Art Prize shortlist, Ukraine

2017

Artadia, USA

Rema Hort Mann Foundation, USA

2016

Joan Mitchell Foundation, USA

2015

Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation, USA

Creative Capital, USA

2013

California Community Foundation, USA

Critic 1

The Ten Thousand Things: on the Practice of Gala Porras-Kim

Xiaoyu Weng

Heaven and Earth interact perfectly, and the ten thousand things communicate without obstacle. Those above and those below interact perfectly, and their will becomes one.

When men die, they enter into history.

One day, their faces of stone crumble and fall to earth.

…

But history has devoured everything.

An object dies when the living glance trained upon it disappears.

— Narrator from Statues Also Die (1953), Directed by Alain Resnais, Chris Marker & Ghislain Cloquet

1.

When our eyes started to adjust, an ethereal world unfolded. It was overwhelming; the emergence of the images—from the murals and the sculptures—created an all-encompassing perspective from above and around, as if I was swallowed and shrunk, and now sat inside of the belly of the cave. As my senses continued to adapt, the details of the images were revealed. In addition to numerous mythological figures and religious symbols, the mural of this particular cave tells an important karma story in Buddhist teaching titled “The Five Hundred Bandits Reaching Enlightenment.” Through a long scroll progressing from east to west, the story starts with the bandits, in the ancient Kingdom of Kosala, South India, causing disturbances. Captured by the army, they were punished by having their eyes dug out. The depiction shows the bandits being stripped half naked with their hair loosened, body covered with wounds, blood spattering the surroundings and the bandits wailing. In great suffering, the bandits are sent out to the wildness of the forest. Then the narrative turns, and the Buddha appears, blowing magical powder into their eyes to recover their eyesight. The bandits converted into Buddhists, practiced, and meditated in the mountains, and all achieved enlightenment in the end.

As I followed the story, what continued to interest me was not necessarily the Buddhist teaching of Karma, but how I found my physical experience uncannily corresponding to the part of the storyline where sight was lost and regained. I couldn’t stop help wonder if my experience and understanding of the caves would be entirely different if I hadn’t been in that disorienting darkness to experience that temporary vision loss. Would I sense differently? Would I perceive otherwise?

2.

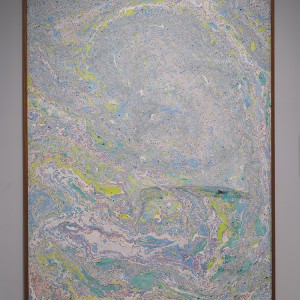

Gala Porras-Kim’s work had been on my mind since the beginning of this trip. At the time, she just completed the triptych The Weight of a Patina of Time (2023) for the 2023 Korean Artist Prize nomination, which compromises three large-scale drawings that provide imagined and realistic viewpoints on one of the dolmens from the Gochang Dolmen Site, located in the current Gochang of the South Korea territory. To the casual eye, the first drawing seems to be a simple pitch-black image, devoid of any content; only the reflective and metallic surface created by layers of pencil graphite strokes give away its materiality. The second drawing is a photo-realistic but black-and-white depiction of the dolmen sitting in the landscape, where trees, bushes and wildflowers hug it. On the lower right corner of the composition, a small plate shows the number 2408 along with a Korean phrase, partially covered by weeds. The last drawing, and the only multicolor one of the three, pulls the viewer into an eerie realm, where nothing is fully formed, and mottled and variegated patterns oscillate between an abstract drawing and a rendering of an organic microscopic world.

The intention here, according to the artist, is to speculate and postulate three different perspectives on the same dolmen from the Gochang Dolmen Site. Found in many parts of the world, dolmens are ancient megalithic structures consisting of two or more upright stones supporting a horizontal stone slab, believed to have been used as tombs or burial chambers during the Neolithic and Bronze Ages. The site of Gochang comprises over 440 dolmens that are believed to have been constructed by the people of the Mumun Pottery Period (lasted from around 1500 BCE to 300 BCE) and are scattered across an area of around 100 square kilometers. Together with sites Hwasun and Ganghwa, it was designated as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 2000.

In Porras-Kim’s work, which took two weeks, two months and four months respectively to complete, the black drawing suggests the dead person’s point of view, the one who might have been buried under the ground of this particular dolmen; the drawing of color pencil and wax proposes a perspective of nature, wherein the seemingly abstract color patterns are supposedly to be viewed from of the insects, animals, and the moss and lichen attached to the stone, growing over the millennia; and the realistic depiction of the dolmen in the landscape represents the human’s perception. The partially covered plate with the number is in fact the UNESCO label to index this particular dolmen number 2408 in the park.

Here, photorealism and abstraction are not in opposition. If described in conventional art history visual analysis terms, the color drawing and the black drawing are both formally abstract. However, in Porras-Kim’s work, these are “realistic” views of “beings” whose experience is intangible to us. What seems nonrepresentational attempts to fill in information that is not always accessible or comprehensible. Displayed side by side, the three drawings show three realities that entangle various spatial, temporal and experiential dimensions. They may be imaginary but are hardly fictitious, and only the limits of our own perception prevent us from substantiating the unperceived as true.

Porras-Kim has previously produced similar works to the black drawing for her other series that investigate archeology objects and sites, including Two plain stellas in the looter pit at the top of the Sun Pyramid at Teotihuacan (2019), which recreates the darkness inside a pyramid in the ancient Mesoamerican city, and Mastaba scene (2022), which portrays the interior of an impenetrable 4,500-year-old Egyptian sarcophagus from the British Museum’s collection. Except for their different titles and dimensions, and varied pencil marks seen only if one looks closely, these graphite on paper works almost look identical. Humorously, Porras-Kim has invited us to imagine, along with her, what kind of scene a dead person (or us ourselves if we were dead) would be seeing lying under the dolmen’s burial ground, inside of the pyramid or the sarcophagus. Moreover, the darkness comes to delineate the limits and constrains of human perception and make visible the blind spots that occlude our vision when recording history and constructing knowledge. These three black drawings become the anchors of the exhibition at MMCA that connect different bodies of Porras-Kim’s work. They not only pay respect to and acknowledge the agency and potential of the ancient spirits but also serve as a spiritual landscape or portals that take our imaginations through the porosity and multiplicity of other experiences and realities.

In some of her earlier work, Porras-Kim has focused on employing artistic gesture as a means to bridge the visual and non-visual and translate seeing to other forms of perceptive senses, particularly knowledges that are formed, recorded, and circulated in ways that are outside of the classical Western framework and European modernity. For the project Whistling and Language Transfiguration (2012), Porras-Kim made a vinyl record documenting her effort in learning Zapotec, an endangered tonal language spoken by the indigenous people of Zapotec in Mexico. Originated in Oaxaca, Zapotec was transmitted until recently entirely through an oral tradition, without written records. An exceptionally tonal language, the content of the words is partly contained within the intonation of speech, to the degree that meaning can be communicated through tones alone and words can be emulated by whistling. While Zapotec is not the only whistled language in the world, it is unique in that it evolved as a strategy of resistance against Spanish colonizers. By communicating through whistling, the indigenous population disguised their conversations as musical diversions. In addition to recording her own whistling of the language, Porras-Kim also transcribed the sounds into musical notes. Similarly, in Muscle Memory (2017), a video work that documents the silhouette of a dancer, who tries to perform traditional Korean chorography without music or any rhythmic or exterior cues. The muscle memory formed by the repetitive movement of the body becomes the vessel to preserve and archive knowledge. Performed each time by different dancer who acts and moves with different body shape, anatomy, and interpretation of the choreography, the particular knowledge is continuously evolved and adapted. Resonantly, in many ways, learning a language through oral tradition is also a way of creating individual muscle memories of facial movements and the tactile sense of the tongue and lips twisting, folding, touching the teeth and collecting saliva. Together, Whistling and Language Transfiguration and Muscle Memory poetically tease out the dynamic tension between collective history and individual experiences imbedded in immaterial records.

3.

Porras-Kim’s practice consistently challenges the human-centric experience and the Anthropocene position of Western epistemology and its colonial projects. In order to do so, she actively engages non-human objects and other unconventional entities such as human remains, dusts, bacteria, and fungi, “ordering” things to ravel and unravel what Michel Foucault calls “the relations (of continuity or discontinuity) between nature and culture.1” Porras-Kim’s practice has a strong anthropological impulse, and echoes with what Descola’s says that “Culture or cultures, as the system of mediation with Nature invented by humanity… includes technical ability, language, symbolic activity and the capacity to assemble in collectivities that are partly free from biological legacies.2” Porras-Kim’s collaboration with nature is never intended to simply romanticize the non-human consciousness or to function as a portal to escape humanly reality, but is supported by a deep understanding of nature as contingent on our anthropological lens: it is only accessible to us through the devices of cultural coding which objectify it: systems of classification, scientific paradigms, technical mediations, aesthetic forms, and religious believes. The artistic manipulations and representations of the body, the object and the environment thus are not an end in itself, but rather a means of accessing the intelligibility of the various structure which organize relations between humans and non-humans. Porras-Kim’s work not only serves as a critique of the opposition between nature and culture imposed by Western epistemology, but more crucially as a dynamic reworking of the conceptual tools employed for dealing with the relationships between natural objects and social beings.

The “natural elements” that Porras-Kim “invites” to collaborate with, such as microbiome, rainwater, or ambient humidity in the environment, have of course always been there. Those who are often neglected have long predated, and will outlive us – myriad fungi, bacteria, and other microorganisms. They are not guests but rather “invisible” hosts to the human eye. In her ongoing series Out of an instance of expiration comes a perennial showing (2022-ongoing), Porras-Kim grows mold spores collected from the British Museum’s storage and encourages them to propagate on an agar-soaked muslin cloth, encased within an acrylic vitrine. Over the course of the exhibition, hairy, fluffy, grey-brown-green mold growths gradually develop and turn the then blank fabric into a rich microscopic world as well as a living painting. A source of concern for conservators at museums, as Porras-Kim notes, “the mold spores ate objects in the collection” over time if not managed properly. Consider an interesting point made by geologist and paleontologist Jan Zalasiewicz, who speculates future extraterrestrial excavators may not think human as the dominant rulers of the Earth worthy of restoring and worshipping, as we have enshrined giant dinosaur skeletons in museum displays as the foreground of the Jurassic landscape. Instead, the yet-to-be-born or arrived explorers may be more concerned with the myriad tiny microbiomes and microorganisms—who have maintained a stable, functional and complex ecosystem in fact required for our survival3. Porras-Kim’s approach echoes Zalasiewicz’s proposition, seeking to acknowledge lives that are dismissed, omitted or trivialized in order to construct a seemingly factual yet often biased and ignorant idea of a history past. “By regrowing them in the space,” the artist continues, “we can see these objects reconstituting into a new form” just as when the top predator dinosaurs vanished 200 million years ago or if humans disappear in the future, the world will present new colors and compositions in its living tapestry.

But Zalasiewicz is not ready to let human vanish yet. He would still like to hope for awe and reverence from our future excavators, and that in their investigation of the Earth’s history they would still find fascination in our own mortal remains. There are no shortage of human remains in today’s museum collections, including those two unidentified human bodies from the Gwangju National Museum in South Korea, who have become collaborators with Porras-Kim. Originating from a centuries-old shipwreck, these remains have been kept at the museum as objects of study, identified only by the codename Sinchangdong43, their humanity stripped away. Intrigued and troubled by this institutional practice, Porras-Kim seeks restitution of these artifacts’ rights to that of the bodies of deceased people. She reminds us that, in many cultures and cosmologies, “it should ultimately be the prerogative of the person to determine what their body becomes after death. Museums have the capacity to recognize that humanity at any time, and should do so.4” Using “necromancy”, a form of divination through pattern-making to communicate with the spirit, Porras-Kim asked the deceased where they would prefer their remains to be buried instead of the museum. The necromancy is achieved through paper marbling techniques— submerging paper in a pan of water, then dropping ink onto the submerged paper to form striations and swirls. The resulting image in A terminal escape from the place that binds us (2022) shows what the artist calls a “potential landscape” that charts topographic terrains. Though the image remains abstract and show no definitive answer with regards to the deceased’s desires, Porras-Kim is able to construct a ritual passage to honor their afterlives.

Perhaps the abstract image is a different kind of wayfinding tool, not comprehensible to our experiential dimension but more straightforward to the consciousness in another scale or realm. Similar to the color drawing from The Weight of a Patina of Time of nature’s perspective on the dolmen, A Terminal Escape from the Place That Binds Us might show us the view from a microcosm where tiny organisms and life forms interact and thrive in ways that are unimaginable and alien to human experiences. Even under the most controlled conservation conditions, organic remains continue to decompose in museums or other storage facilities, whether through insects, bacteria or fungi growth or by the gradual chemical effects of degradation and oxidation. Perhaps, the deceased have reincorporated their spirits back into nature, diffused from the museum, and are now resting and evolving with the lakes, rocks, soil, and many strata and layers of organic and inorganic, living and non-living worlds.

4.

The conceptual tools Porras-Kim employs to renegotiate the binary opposition between nature and culture imposed by the Western epistemology often turn on the creative reframing of practices that modern science and technology have hastily denounced as superstition, irrationality, or primitiveness often without fully understanding (or at times deliberately refusing to understand) their multiple and varied cosmologies. In addition to facilitating communications with the dead, Porras-Kim summons other “spirits” such as exhalations, moistures, soil, and dust as what the artist posits to be “physically and figuratively trapped within institutions”5 and creates “conducive environments” to let them out, including planning and organizes rituals and ceremonies, with the cooperation from the institution’s curators and conservators, to restore museum objects’ spiritual life and awaken their suppressed capacities for magic and power.

In Forecasting Signal (2021-ongoing), Porras-Kim set up an oracle which conjures an artwork-to-come: a dehumidifier extracts ambient water from the exhibiting space; as the water accumulates and condenses, it filters through a hanging burlap sheet saturated with graphite powder extended from the ceiling and drops onto a blank canvas panel place on the floor, where an artwork-as-prophecy is created over the course of the exhibition. Echoing those seen in Eastern Asian ink paintings, the at times spontaneous and fluid, at others chaotic and energetic textual depth and ink layering divulge a prophecy of the particular site, be it a conventional white-cube gallery or a historical- monastery-turned-museum. In Precipitation for an arid landscape (2021), the artist looks into the troubled history of the excavation of the Chichén Itzá cenote, a sacred Mayan sinkhole located in the Yucatan peninsula of Mexico, a geologic landscape dense with caves. Believed by the Mayans to portals between the secular realm and the netherworld, and temporary deswellings of Chaac, the Mayan god of rain and thunder, these openings became burial sites for human bodies and funerary objects, placed according to ritual. to ensure that the rain god might access them. As part of archeological excavations during the early 20th Century, the sinkholes were dredged and the sacrificial artifacts and remains were removed and ultimately became the holdings of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology collection at Harvard University. For the sculptural part of this series of work, Porras-Kim mixes copal, a meltable tree resin used to backfill a void from which an artifact has been removed during archeological excavations, with dust collected from the storage area where the artifacts are stored at the Peabody Museum to make a rectilinear slab or a cube sometimes. This object, placed on a platform or pedestal, is meant to be splashed by collected rainwater during a daily ceremonial procedure, of which the format and participants are interpreted and determined by the exhibiting institution. In doing so, the sculpture assumes a new life that facilitates the reunion of the sacrificial artifacts and remains with the Mayan rain god.

5.

Geochemist Vladimir Vernadsky describes life itself as a continuous process of happening. Vernadsky speaks in a profound geological spacetime, which Porras-Kim’s practice echoes. In her works, natural time, experiential time, death time, spiritual time, decay time, museum time and historical time intertwine and collide in an ever evolving and becoming artistic configuration. On the one hand, though a conceptual artist at heart, Porras-Kim is never a conventional conceptualist. Ideas that come like a flash of insight or those that are mere conceptual gestures are not the point. On the other hand, highly research-based, Porras-Kim’s practice is also not a mere visualization of her research topics. Instead, process and materials are crucial, and the politics of aesthetics are imbedded in the subjects, mediums, surrounding infrastructures, participants and audiences; together constituting the complexity and depth of her work.

The choice of drawing as a core medium with pencil and graphite, for example, is deliberate, as according to the artist, these are the most accessible and versatile artistic materials in everyday life. The resulting work, as intended by the artist, therefore, stands as sketch, study, and rebellion against “traditional” oil painting in particular, which can potentially “liberating them from the pedestal and confines of a capital “A” in considering what constitute an artwork.6” The accessibility and fluency of drawing with paper and pencil becomes a tool and an exercise for Porras-Kim to learn from her subjects. Mostly made from photographic documentation and often similar to the original scale of what’s being depicted, the drawing process not only allows Porras-Kim to observe and study every tiny and distinctive detail in the cracks and patterns of her subject but also to reach and test certain limits, whether it is the size of the objects in relation to her own body, or the physical endurance in the painstakingly long hours and repetitive movements required. In this way, Porras-Kim’s drawing process becomes performative: the drawing process becomes a ritual—not unsimilar to the rainwater splashing in Precipitation for an arid landscape—that goes beyond the mere representations of the subject maters but actively reproduce and reconstitute new social relationships and cultural realities for them.

6.

Unsurprisingly, given her insightful and witty engagement with not only many historical artifacts but also various aspect of museum and institution administration, many of the productive discussions around Porras-Kim’s work have focused on the complex issues around repatriation and its relationship with museology, cultural heritage, and policymaking in an era reckoning with past and ongoing colonialism. The 1953 French cinematic classic Statues Also Die first brought to light these issues in a widely circulated format and remains one of the most important and extensively quoted work. The directors Alain Resnais, Chris Marker and Ghislain Cloquets searingly criticized the damaging impact of colonialism through the lens of European museum collections of ritual and spiritual artefacts from Africa. Because of its critical stance, the film was censored by the French National Center for Cinematography and was not allowed to be shown in French cinemas until 1964. Porras-Kim shares many sensibilities with the film, particularly the acknowledgement of the multiple lives of historical objects as ritual objects and spiritual objects besides, originally, or perhaps more importantly. It is clear that much of museum practice today reflects and indeed continues a troubled legacy, an outdated structure that belongs to the specific technology of the colonial time and epistemology hardwired into Western institutions.

For many, repatriation is understood as geographical meaning of physically returning the artifacts to their counties or places of origin. For Porras-Kim, this is far from being true or enough. There is much work to be done beyond just geographical borders and nation state politics to continue, for example, the restoration of cultural identity, the reframing of legal and ethical frameworks, the reconciliation of historical injustices, colonial exploitation, and cultural imperialism, and the rewriting of history. By creating a conceptual structure and focusing on process—through its performative repetition and duration— Porras-Kim’s practice intends to shape cultural norms, identities, and social structures surrounding these crucial issues. Her practice integrates itself into the everyday, and the agency to cross boundaries, to bridge life and death, and to open up multiplicity.

I am not surprised that as I wander through the thousand-year-old Mogao Grottoes in the Gobi Desert, thousands of miles from home, I have Porras-Kim’s work in mind.

1 Michel Foucault, The Order of Things (London: Routledge, 1975), 412.

2 Philippe Descola, The Ecology of Others, trans. Geneviève Godbout and Benjamin P. Luley, (Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press, 2013), 35.

3 Jan Zalasiewicz, The Earth After Us: What Legacy will humans leave in the rocks? (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 191-218.

4 Defne Ayas, “Gala Porras-Kim, A terminal escape from the place that binds us,” 13th Gwangju Biennale, https://13thgwangjubiennale.org/artists/gala-porras-kim/.

5 A terminal escape from the place that binds us, Commonwealth and Council, November 6 – December 18, 2021, https://commonwealthandcouncil.com/exhibitions/a-terminal-escape-from-the-place-that-binds-us/press.

6 Gala Porras-Kim, Author’s conversation over zoom, September 2023.

Critic 2

Beyond the Cabinet of Death, Living Temporalities

Hyunjin Kim

“Surely there is something insuperably barbarous in the custom of museums.”

Maurice Blanchot1

A concrete stela, ancient artifacts, a video recording of a female dancer’s silhouette, stones, a vitrine for relics, representational and abstract drawings in graphite, cubes, a topographic model of an archeological site and field recording, paintings that sit somewhere between abstraction and stain, heavy and imposing sarcophagus from an ancient tomb, and drops of black liquid dripping from a massive curtain. Viewing Gala Porras-Kim’s exhibition at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea (MMCA) is like walking into a group show consisting of works made by different artists. In each of her works, Porras-Kim adopts a different method and chooses from mediums that span across drawing, sculpture, video, installation and sound. For the past decade, the artist has been investigating museum artifacts, archeological sites, and ancient architectures with keen interest in their original mode of being as well as their repatriation. Such concerns manifest themselves in the diverse range of her work, where the choice of medium accords with how Porras-Kim connects with the artifacts in question, broods over them, and calls attention to where they originally belong. Some of them find expression in tangible forms such as drawing and sculpture, while others culminate in intangible mediums such as sound waves or movements recorded in video. Furthermore, Porras-Kim presents the growth of mold and moisture in the air that continue to change over the duration of the exhibition, calling attention to other forms of life and agencies within the exhibition space. What begs the question here is the common thread that runs through these seemingly discrete pieces.

Porras-Kim is interested in what has been discovered at old archaeological sites, especially those of ancient Egypt and Maya or the prehistoric dolmen sites. Proposal for the Reconstituting of Ritual Elements of the Sun Pyramid at Teotihuacan (2019) consists of replicas of the two monoliths at the eponymous site, along with Porras-Kim’s letter to the coordinator of museums and exhibitions at the National Institute of Archeology and History in Mexico City. Teotihuacan, meaning “City of Gods,” is known for its large pyramids, among which the Sun Pyramid is attributed with special astronomical significance for its alignment with the position of the sun. Although the two monoliths, thought to have served ritualistic purposes, used to sit inside the top of the pyramid, they have been moved to the museum for preservation and display, leaving their hollow negatives behind. Their replicas have been produced by Porras-Kim with permission from the said institute, and, in her letter to the institute, she proposes reinserting them to where the original monoliths were, which amounts to a call for the need to restitute their innate spiritual significance. Porras-Kim emphasizes the possibility of channeling the efforts into the reconstruction of the “exterior” of the ancient architectures—once displayed in the LACMA which held and exhibited those monoliths—into resuscitation of spirituality inherent in them. Reinserting the artist-made replica stones into the top of the pyramid would be one possible instance, which seeks to sustain the link between their transcendental, spiritual significance and what they were intended for.

Next to these stones and the letter is Two Plain Stellas in the Looter Pit at the Top of the Sun Pyramid at Teotihuacan (2019), a graphite representation of the view inside the top of the Sun Pyramid. Like some of its monochromatic predecessors, Two Plain Stellas have been worked over a prolonged period of time, with the artist repetitively and patiently filling the surface with pencil marks. The utter darkness amounts to a poetic invocation of the cosmology reflected in the pyramids of Teotihuacan, a city built as a tribute to the gods. The enormous amount of labor that has been put into building the pyramids, through which the ancient desperately sought to reach the divine and immortality, finds its parallel in the length of time that Porras-Kim has committed to the surface by filling it meticulously with thin layers of graphite.

Dolmens are one of the oldest tombs from prehistoric times. The Weight of a Patina of Time (2023) is a new work made for the occasion of Porras-Kim’s exhibition at the MMCA, for which she visited and studied the dolmen site in Gochang, North Jeollabuk-do Province. Over 500 dolmens, designated as UNESCO’s World Heritage Site in 2000, provide a glimpse into the funerary and ceremonial customs of the ancient. Prior to the archeological assessment, however, the dolmen site was deeply integrated into the quotidian life of the locals, where they would sundry vegetables and laundries. Such different modes of being that cut across multiple temporalities of this dolmen site have caught Porras-Kim’s attention, which resulted in a two-dimensional triptych: The first is a graphite drawing depicting what the dead would see in a dolmen—in other words, the pitch dark inside the sarcophagus, which alludes to its funerary purpose; one in the middle is a naturalistic rendering of the dolmen as we see it today, that is, as a historical site and a tourist spot; the last work traces a magnified image of moss that grow on the surface of the dolmen. The two seemingly abstract images on both sides of the representational drawing are in fact representational themselves: the left portrays what lies before the eyes of the dead and the right living creatures. One communicates with the time transcended, while the other with the time of the living.

Museum Sickness2

“The museum is indeed the symbolic place where the work of abstraction assumes its most violent and outrageous form. … this space that is not one, this place without location, and this world outside the world, strangely confined, deprived of air, light, and life…”

Maurice Blanchot, excerpt from “Museum Sickness”3

Sunrise for 5th-Dynasty Sarcophagus from Giza at the British Museum (2020) suggests that the Egyptian sarcophagus, in which a dead body of a pharaoh or aristocrat is placed, face east according to the ancient customs. The arrow drawn on the floor marks the direction toward which the original sarcophagus in the British Museum should be rotated, while its reproduction in the exhibition is positioned to face east—the direction in which the sun rises and its mastaba lies. Mastaba Scene (2022) depicts the perspective of the dead lying inside the sarcophagus—in other words, the unfathomable depth of darkness, which tends to be wiped out by the lighting in the museum. Porras-Kim has embarked on these works as she began exploring the British Museum’s collection of ancient Egyptian and Nubian funerary art during her time at Delfina Residency in London in 2021. In her letter proposing a drawing of a ancient desert museum large enough to envelop the vitrine, with corresponding folds, in which the granite ka statue of Nenkheftka is enclosed, Porras-Kim writes as follows:

“Since you “hold the largest collection of Egyptian objects outside Egypt and tell the story of life and death in ancient Nile Valley,” it could seem daunting to understand and accommodate so many people’s eternal plans. Fortunately, many of the labels you have provided in your current display already outline the specific needs for their exposition. These guidelines might not interfere with the museography and the day to day activities at the museum and could be an opportunity for curating for that ancient audience to consider their positioning and views for sights beyond the grave. Such a small step to repairing the potential disruption caused by the relocation for the people who planned so well, can expand our knowledge of aspects of life which might be lost to us now.”4

Museums are deeply implicated in the Western modernity. The inseparability between the British Museum and colonial modernity is evidenced by the fact that it holds the largest collection of ancient Egyptian artifacts outside of Egypt. The museums in the West find their origin in the cabinet of curiosities—be it cabinet de curiosités or Wunderkammer—of the European aristocracy. Not only do they store and showcase the so-called “rarities of the world,” a notion based on the exoticism that renders the non-Western civilizations the mysterious other and therefore an object of curiosity, but they also acquire their collections through colonial exploitation and looting, and thus serve as the core space that inherits the colonial legacy of Western modernity. While such implications inevitably raise questions regarding repatriation of the looted artifacts to the country of origin and therefore ownership over cultural property in the legal discourse today, Porras-Kim takes on the question of repatriation and restoration on a more fundamental level, which pertains to not only their place of origin but also their “original” context—that is, concerns over the divine, religion, and afterlife out of which such relics were born. What the artist asks is how we are to approach and restore, for example, the notion of immortality inherent in these ancient relics from the ancient’s point of view—the intended audience of the mysterious artifacts and sublime statues or buildings. All of these concerns bear on the various proposals Porras-Kim makes to the institutions, where she questions the ways in which we could provide the spirits of the dead, alongside the associated artifacts, with comfort and respite from the forced acculturation or displacement. For instance, Porras-Kim takes advantage of the opportunity opened up by the fire at the National Museum of Brazil in 2018—which marked its 200th anniversary of its foundation during the Portuguese colonialism in 1818—during which Luzia, a name given to the oldest mummified woman found in the Americas, has also partially been lost along with the museum’s many other collections. Porras-Kim insists on cremating the rest of the body that was recovered, which would free her from the museum’s grasp as a historical object and finally put her to rest. Her insistence entails seeing Luzia, thought to have been a 25-year-old woman some 11,500 years ago, as a person and not an artifact for genomic reconstruction.5

Most of Porras-Kim’s compassionate letters were unanswered, and none of her proposals have been accepted or realized yet. They nevertheless remind us of how the act of collection and exhibition amounts to deracination of the ancient objects, dehumanizes the dead in the name of museological practice, and severs the cosmological connection and communication between spiritual worlds that transcend not only our understanding but also our being. Instead of serving as a space devoted to artistic creation, the museum “forces us,” Maurice Blanchot claims, “by means of an exclusive violence, to set aside the reality of the world that is ours, with all of the living forces that assert themselves in it.”6 In describing the pain of seeing the restored mosaics of Umayyad Mosque at an exhibition space, estranged from their place of origin, Blanchot names the museum a violent and blasphemous place of abstraction. Unlike the “real space, thus, a space of rites, of music and of celebration,”7 a space of exhibition is open for everyone from all over the world without imposing a particular theology. Nevertheless, Blanchot warns us, what it does is no different than the satisfaction of Lord Elgin, an imperialist who stole marbles of the Greek Parthenon and brought them to London. Objects such as these marbles “offer themselves to us…in the secret essence of their own reality, no longer sheltered in our world but without shelter and as if without a world.”8 The grief of seeing these objects that have been abducted by the archaeologists corresponds to the irony of the museum, a term that signifies essentially conservation, tradition and safety, whose authority grants status of art to things once they are congealed into permanence without life. For Blanchot, museums are where “this lack, this destitution, and admirable indigence”9 is laid bare in one way or the other. Perhaps it is what Blanchot has called “a radiant solitude,” a presence of a world, that Porras-Kim sees in the artifacts that are kept in the safety of the museum, or, in other words, hidden away from their place of birth.

In her two dimensional work titled A Terminal Escape from the Place that Binds Us (2021), Porras-Kim attempts to communicate with a mummy that dates back to the 1st century from the Gwangju National Museum collection. Captivated by the shamanistic traditions in South Korea that revere spirits of ancestors through various rites, the artist spoke with a number of South Korean museum curators, only to confirm that the dead are seen as objects of research and conservation in their practice as well, belying the cultural expectations. Porras-Kim makes yet another proposal in this regard, insisting on figuring out where the mummy wishes to be buried via means of shamanic ink divination. This process involves dropping ink in a puddle of water while potentially making contact with the spirit of the dead, and knowing that there could be information of a location within the incoherent patterns it creates, and transferring them via paper marbling, which could contain the wish of the spirit. The colorful swirls created thus, which give the look of modern abstract painting, not only potentially speak on behalf of the spirit but also serve as a testament to Porras-Kim’s commitment to their ontological reinstatement.

Such a practice of hers belongs to a type of institutional critique situated in the tradition of the avant-garde art. Her letters provide a glimpse into the activist side of her practice, evidenced by Porras-Kim’s insistence on showing respect for the dignity of the dead, the ancient cosmology, and the spirits of the ancestors—in other words, things that lie beyond the purview of Western rationality and by extension colonialism. These are addressed to none other than the museums, the coffin-like institutions that exemplify the complex matrix of Western rationality where law, bureaucracy, and academic specialization intersect. Instead of opting for radical interventionist tactics commonly associated with such a practice, however, Porras-Kim employs rather familiar, traditional mediums such as drawing, and sculpture for unfolding her profound ontological insights. While her proposals, persuasive and composed in their style and tone, is cut across by the meridian of the animistic world of spirits, the lyricism of her work—evident in the night and the stars, the glimmer of sun shining through closed eyes, the asymptotic horizons, or the songs made in tribute to the forbidden love between two brothers—carves out a soft, delicate space for poetics. In Porras-Kim’s work, the archeological artifacts shed themselves of their designation as object of knowledge, marked by titular information such as chemical and material composition or chronology, and reach out to the viewer in their ontological precarity and loss, their mysteriousness and solitude. Through such a nuanced approach, Porras-Kim enables the viewer to resonate deeply with the accountability of museums as a space for the spirits of the ancient and their worldview as well as restoration of their dignity but also the ontology of archeological objects.

Porras-Kim’s lyricism persists in Asymptote towards an Ambiguous Horizon (2021), a series of twelve graphite drawings depicting the changing landscape of Göbekli Tepe in Turkey—a neolithic World Heritage Site designated by UNESCO—over twenty-four hours at a two-hour interval. The work also features a soundscape of the site, which is played back from a scaled-down topographic model of the site. Göbekli Tepe or “Potbelly Hill,” one of the world’s oldest known human-made structure that dates back 12,000 years, harbors a secret of an ancient architectural technology that surpasses the Pyramid of Giza or the Sumerian civilization in time, with the most notable feature being twenty or so circular enclosures made up of T-shaped stone pillars that amount to nearly two hundred in total. The site had been buried 760 m above sea level when it was discovered by coincidence, and excavation is still ongoing. Although it is believed to have been a temple, some speculate that it was built to observe Sirius or other astronomical events.

When the site visit became unfeasible in 2020 due to COVID, Porras-Kim sought help from astronomers and Google Earth for her drawings: the skyscape, northwest to the site, has been drawn according to the star formation from 12,000 years ago provided by an observatory, whereas the current day landscape is based on images generated by Google Earth, where the user is able to change the position of the sun and by extension the lighting of the image. The drawings of the ancient skyscape juxtaposed with the modern landscape reconstruct the twenty-four hours at Göbekli Tepe, during which heaven and earth draw ever closer to each other at the horizon but never meet. These lyric drawings, which aspire to the primordial and incomprehensible time, quietly move in and out of multiple guises—a personal tale, myth, mystery, and state-owned resource—as they, in a purely auditory sense, traverse across the soundscape composed of various sources ranging from the wind passing through the site to video- and voice-recordings pertaining to the site.

Soul Design by Mold and Moisture10

No actual artifacts are found inside the vitrine. What persists before the viewer’s eyes, however, are their semblance, their existence which is their soul. In her solo exhibition at Leeum in 2023, Porras-Kim replaced one artifact at the museum with paper pieces arranged in a way that casts a shadow identical to that of the original object when lit by the lighting. Depending on the angle from which they are looked at, the shadow blurs or sharpens, in the latter case of which reveals the enigmatic, captivating contours of the replaced object. Through this shadow constantly coming in and out of existence, the artifact enters a nonmaterial state, or, in other words, engages in spiritual communication.

“What if we were to imagine the soul as an “event,” as something that cannot be owned but only exists in the intermediary realm? Wouldn’t this enable us to pose the question of animism differently—not as a question of what possesses a soul, but as a question of the different forms of being animated and animation, understood as a communication event? What if “the soul” was the medium of such event? After all, each of us is capable of distinguishing an animated conversation from an un-animated one—however, articulating this difference or even objectifying it is incomparably harder. And “exhibiting” this difference can virtually only be done in the form of the joke or the caricature.”11

The aforementioned work in paper fragments and their shadow, Gourd-shaped Ewer Decorated with Lotus Petals Display Shadow (2023), is shown inside of glass vitrine at the antiquity section of Leeum, which brilliantly resonates with what Anselm Franke explains in his notion of “soul design,” amounting to a witty sculptural event that sets in motion the animistic property of the archaeological object. This is to say that Porras-Kim’s work entails far more than simply preaching how ancient spiritual traditions ought to be respected by the museums. Porras-Kim engineers and facilitates “animated conversations” in her works—or objects. In fact, animism is native to conversations in contemporary art, and she employs various conceptual strategies to animate such conversations in visually concise, minimalist forms.

303 Offerings for the Rain at the Peabody Museum (2023) is a two-dimensional life-size reproduction of ancient artifacts discovered from the Chichén Itzá cenote, one of the sacred sinkholes with exposed groundwater on the Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico, within the dimension of 183 × 183 cm (or 72 × 72″). Originally intended as offerings to Chaac, the Mayan god of rain, these objects were found submerged, dredged and are currently in the storage of the Peabody Museum at Harvard. They have inspired Precipitation for an Arid Landscape (2021)12, a work that takes copal13—one of the most commonly found material in the cenote and a binder—and dust collected from the storage at the Peabody. It is placed inside a glass case full of moisture, which is the result of instructing each exhibiting institution to devise a strategy for bringing rain water to the installation. According to Porras-Kim, this is a reunion between Chaac and the offerings made to him, or consolation for the displaced spirits, accomplished at last by taking advantage of the very discretionary power of the museum.

For some of her work, Porras-Kim regularly makes requests for particular arrangements for moisturization to the museums. In Out of an Instance of Expiration Comes a Perennial Showing (2022), Porras-Kim cultivates mold spores obtained from the museum storage on a muslin cloth by providing it with moisture. The mold spreads and evolves over time, producing a new image of abstract patterns on a daily basis. In the back end of the exhibition space hangs Forecasting Signal (2021), where invisible moisture collected by the industrial dehumidifier finds its way onto a hanging burlap canopy soaked in liquid graphite. The water, when accumulated enough, drips through and leaves its trace on the panel installed underneath. The drops of black liquid represent the amount of moisture accumulated throughout the exhibition period, “signaling” the minute changes in the indoor climate such as humidity level. The climate controls of the museum are a telling sign of its built-in aspiration toward a clinical space, a sealed cube where microorganisms remain inactive. The events taking place during the exhibition are none other than the interaction between organisms and the microbiome that animates one another. There is a bizarre sense of humor or irony in bearing witness to the reincarnation of what ought to have been exterminated in the museum. What first catches the attention of the visitors in these two works are the patterns of the molds and graphite stains or the way that the burlap hangs from the ceiling. Although for the viewer they take the guise of traditional mediums such as drawing, sculpture or installation, the set of concerns and performative gestures that Porras-Kim presents before her audience, from ritual for spirits of the ancient to exhibition that consists of conversations between objects, spring from the comprehensive inquiry into things that ought to inhabit the museum.

Porras-Kim has continued to produce works that reflect on the symbolic structures of the Western rationality and colonialism through research into specific archeological sites and collections, imagination and ontological understanding of archeological objects. Her works occasionally manifest in poetic moments of coming into contact with the animist cosmology, where, traversing a wide range of approaches—institutional-critical, conceptual, poetic, pictorial, etc., the soul design of objects in contemporary art intersects with ancient cosmology. Porras-Kim appeals to the spirit inherent in the ancient objects as if facing an actual person in her own right, summons the stars in the ancient night sky as if reciting poems, sees and speaks on behalf of the dead and their relics, and engenders conversations between the museums and their macrobiotic environment. The archaeological objects are, in some sense, the age-old diasporic beings. Communicating with these objects takes place in the communal time shared between the humankind and their ancestors. To whom does the death of the ancient belong? What does it mean to “own” an object from a world that far exceeds our measure of understanding? In what ways should museums exercise their discretion? What do we see and not see in the museum—a space saturated with the very act of seeing? How do archaeological objects and works of art pave the way for animated conversations? These are critical and crucial questions that lie in Porras-Kim’s decade-long artistic pursuit. In conjunction with these inquiries, the artist demands and exercises alterations while relaying age-old yearnings from the afterlife. Her works are vibrant—individual entities that manifest vitality, memory, and solace. Not only do they aspire to communal restitution, but they also shine through as events of animism.