Bang Jeong-A

Bang Jeong-A is an artist based in Busan who has consistently addressed the theme of “the here and the now” through her painting. She strives to relate on canvas the stories obscured behind the ordinary and familiar scenes of our contemporary society. She has held solo exhibitions at Busan Museum of Art (2019) and Art Space Pool (2008), and her works are housed in the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art and Busan Museum of Art.

Interview

CV

Education

2009

MFA, DongSeo University, School of Design, Busan, Korea

1991

BFA, Painting, Hongik University, Seoul, Korea

Selected Solo Exhibitions

2020

back view series, twelve domes, Art District, p, Busan, Korea

2019

Bang Jeong-A : Unbelievably Heavy, Awfully Keen, Busan Museum of Art, Busan, Korea

2018

Where It Heaves And Churns, emu artspace, Seoul, Korea

2017

Ggwak, Peong, Haek, Zaha Museum a center for contemporary art, Seoul, Korea

2015

The Tilted World, KongKan Gallery, Busan, Korea

2015

Uncanny Days, Trunk Gallery, Seoul, Korea

2012

HUL!, Gallery Arirang, Busan, Korea

2008

The World, Art Space Pool, Seoul, Korea

Selected Group Exhibitions

2020

the Painting & Narrative, Museum SAN, Wonju, Korea

SaSam Art Exhibition, Jeju 4·3 Peace Memorial Hall, Jeju, Korea

Savage Dreams, Art District, p, Busan, Korea

2019

Hack Mong(Delusions of Nuclear Power)3: The Green Camouflage, emu artspace, Seoul, Korea

Artist’s Book, Robotfreud, Busan, Korea

2018

Imagined Borders, Gwangju Biennale 2018, Asia Culture Center, Gwangju, Korea

A Literary Picture Of The New Woman, Kyobo Art Space, Seoul, Korea

Busan Returns, F1963 Seokcheon Hall, Busan, Korea

A Bad Dream2, Democracy Park exhibition hall, Busan; Eunam Museum, Gwangju, Korea

2017

Platform of the peace, New Treasure Art Gallery, Yangon, Myanmar

Two Mother, Shinsegae Gallery Centum City Branch, Busan, Korea

Mihwangsa, A Beautiful Temple in the Southernmost Village, Hakgojae Gallery, Seoul, Korea

2016

Hack Mong, G&Gallery, Ulsan, Korea

KIM HYESOON – Bridge, Trunk Gallery, Seoul, Korea

2015

Korean Art 1965-2015, Fukuokan Asian Art Museum, Fukuoka, Japan

Asian Highway Exhibition, SeokDang Museum of Art, Busan, Korea

Roof association, Space Heem, Busan, Korea

Through the eyes of the mother, Korean Cultural Center of Chicago, USA

2013

Facade Busan2013, Busan Museum of Art, Busan, Korea

Lives and Works in Busan, Sungkok Art Museum, Seoul, Korea

2012

Here are people, Daejeon Museum of Art, Daejeon, Korea

No Excavation, Art Space Pool, Seoul, Korea

A Monumental Tour, Space*C, Seoul, Korea

10th Anniversary of the Ha Jung-woong Young Artists Invitation Exhibition, Gwangju Museum of Art, Gwangju, Korea

Day of Confidence, Art Space Pool, Seoul, Korea

BlueDot Asia2009, Hangaram Art Museum, Seoul Arts Center, Seoul, Korea

New Acquisitions 2008, National Museum of Contemparary Art, Korea, Gwacheon, Korea

2008

Mirror Mirror on the Wall: Stories about People in Art, National Museum of Contemparary Art, Korea, Gwacheon, Korea

Art at Home, Wonderful Life, DOOSAN Gallery, Seoul, Korea

Busan Art Now : Since 1928, Busan Museum of Art, Busan, Korea

2006

Asia Art Now (Alternative spaceLOOP, SsmzieSpace, Gallery Soop / Arario / Beijing)

2004

The Realing for 15 years, Savina Museum, Seoul, Korea

Painting&Collection, Kumho Gallery, Seoul, Korea

1994

15 Years of Minjung Art : 1980 – 1994, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, Gwacheon, Korea

Selected Awards

2002

13rd Pusan Youth Arts Award, KongKan Gallery, Busan, Korea

2002

2nd Ha Jung woong Young Artists prize, Gwangju Museum of Art, Gwangju, Korea

Selected Collections

National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea

Busan Museum of Art

Daejeon Museum of Art

Gyeongnam Art Museum

Fukuoka Asian Art Museum

Critic 1

In recommendation of Bang Jeong-A

Kim Jaehwan. Curator, Gyeongnam Art Museum

Bang Jeong-A has been painting for over 30 years. Her work has been assessed within such notions as second-generation Minjung Art, realism, feminism, and figurative art based in Busan. However, she refuses to be limited to these keywords. Indeed, interpreting her work through any one frame is challenging. The fact that Bang Jeong-A’s work holds pertinent to a certain point of discussion in contemporary art while remaining stubbornly in the realm of painting relates to her refusal to be incorporated into a particular norm or grammar.

Bang Jeong-A tends to refer to her work as “[her] own kind of realism.” This is because her paintings refute convention and capture scenes of everyday life through an active interpretation of “[her] own” gaze. In other words, the artist may fit within the broader framework of “realism” for making remarks on reality but builds an oeuvre of “[her] own” by placing a heavier emphasis on interpreting the “everyday.” Thus, as she continually reflects upon her painting’s format, to reject the typicality of the medium and speak of society’s macro-and microscopic issues through it, her works become a point for significant discussion within the context of contemporary art.

Bang Jeong-A’s works from the 1990s to the late 2000s have as their central theme an event or figure(subject) surrounding the artist. Here, women’s issues, reflecting her life experiences as a Korean woman, are treated light yet serious. Of course, the artist’s gaze is not limited to the realm of everyday life. Bang Jeong-A has also continued to respond to the absurd events in Korean society since the 1990s. Her work in visualizing events that had direct and indirect implications on her life, from contradictory social structures and threats to nature and society, such as the Four Major Rivers Restoration Project and nuclear power plants, faithfully persisted. Moreover, the artist’s oeuvre further expands into a surreal space where historical events and social factors are reconstructed in fragments. This world contains an accusation against human civilization that is destructive to nature; a glimpse of the tendency to symbolize the vitality of nature with images of water can also be observed.

In strict terms, realism in the narrow sense has an unattainable objective. Achieving realism in painting, in particular, is even more fictional in that it requires a physical transformation of the real three-dimensional world onto a two-dimensional canvas. Thus, what matters is how much of the world’s hidden truths can be revealed in the world realized by the artist. Bang Jeong-A’s painting is interesting, for in her oeuvre built over the past 30 years are moments that our society’s hidden truths unfold. These moments are made possible by her unique technique in defamiliarizing the everyday and sensualizing narrative language. This is the point where the artist, who has been painting for a long time, can pry open a new world before us. Contemporary art may seem to concentrate upon conceptual inquiry in revealing new worlds. However, through a consistent exploration of visuality, Bang Jeong-A refines the senses that perceive and conceive our world to make it possible to imagine another world within it.

The painting Moment When She Raised Her Hand (2019) puts at its center a fountain of one subterranean shopping mall in Busan, where senior citizens, arranged between multiple pillars, wearily spend their free time. Individual figures are wrapped in blue filaments that look like the forest’s neural network in the movie Avatar. This painting grasps at the continuity of time, in which the worlds of reproduction and energy interconnect. Unrealistically rendered from the beginning, the space turns even more disparate by putting together an impossible combination of people. As such, Bang Jeong-A visualizes a surreal conversion to present her own kind of realism on canvas that is anything unlike “realism.”

Critic 2

Korean Illusion

Lee Byunghee (art critic)

Upon digging, out it comes.

The earth rises sharply, indents harshly, or simply erodes. A deep canyon wrinkles the land between volcanic cones, mountains, capes, and sierras. Through erosion, subsidence, ascent, and descent, the earth builds landforms high and low, and the wind stirs the atmosphere. Among these topographies formed across high and low elevations are the artificial creations called cities. Unlike the land in nature, which consists of diverse organic matter, the land in cities is a composite of cement and asphalt concrete. Beyond the canyon and around a cliff of steel-reinforced concrete, the wind traverses an overpass and whispers through a tunnel. It seeps into the gossamer lightness of a prickly, bumpy heterogeneity, then coils around the nimble speed of a flat, smooth uniformity.

In Korea, urban development has always included plans to artificially cover the earth. Surfaces of dirt and soil are repurposed into urban byproducts, such as empty lots purchased for development profit or landfills for burying domestic and commercial waste. These urban development projects for modernization accelerated during Korea’s military dictatorship. Just below the skyline of high-priced, high-rise buildings emerged the plateau of a widespread shantytown. Those stranded on these hills, lacking sewage systems and even freshwater supply, had no choice but to dig wells. Coal and oil were extracted from the earth for a faster source of energy. After much digging, the earth was buried again. Now digging unearths a mixture of industrial and military waste everywhere.

In the background of Bang Jeong-A’s I dug, and it came out. (2021), we see mounds of black soil dug up from the ground, as noted in the title. These mounds grow into a ridge, serving as the picture’s backdrop, whose surface lines build and continue into a three-dimensional space before giving way to an abstract image of urban acceleration. In this setting fit for a science-fiction film, oddly enough, an old wooden bench runs horizontally across the painting. On one side sits a masked person in an awkward position, as if poised to leave at any moment. A hand appears lost, having failed to catch something, while the head joins with the black mounds of soil. At the end of their gaze, an ominous figure crouches, shrouded in cloth similar to a magician’s robe. Its folds seem to hide a weapon or certain danger. As the robe twists and turns, it connects the bench with the ground. It is difficult to tell whether the figure was born from the ground, as an ill-omened thing snaking upwards, or from the surrounding atmosphere, slowly sucking out its energy.

The black soil comes from Busan Citizens Park. The site used to be Camp Hialeah, a US military base, which, after closing in 2006, was handed back to Busan in 2010 and eventually reopened as Busan Citizens Park in 2014. As recently as 2021, heavy metals and waste oil continue to be detected in the park’s soil. Let’s return to Bang Jeong-A’s artwork; here, the animated black and vivid red hues are enough to transform a grim slice of reality into a surreal one.

Busan as a site may be distinct, but as a place, it is ordinary and grounded. However, with the reality of Korea being unrealistically realistic and objective, its placeness borders on the utopian. Time and history have had a hand in creating this state. While the nation underwent colonization, liberation, and the Korean War to reach this current era of globalization, the US military became international citizens based on the Korean Peninsula. Toxic matter released from their particular campsite remains alien from the native soil and is left abandoned, unaccustomed to its place.

The contaminated soil—found wherever you dig—is matter left neglected, caught between unstable history and geological time. It is impossible for anyone to predict or verify accurately the effects and consequences of any one matter. However, anxiety spreads not from lack of information or scientific uncertainties but from concealment and ignorance and becomes a political tool. Thus, as uncertainty is the aesthetic of nature, anxiety surrounding (im)possibilities is the core of politics. How any matter came to be a double-edged sword, a dangerous tool or a defense against it, is ultimately due to the way politics determines the future of a community steeped in anxiety.

The issue of contaminated soil in the restituted US military base is an ongoing issue for both the Korean Peninsula and international politics. Korea’s search for a political solution in relation to the US military proved extremely difficult, however. From Dongducheon to Yongsan, Pyeongtaek, and Busan, digging any formerly US-owned land after restitution turns up contaminated soil and an emotionally bruising modern history of Korea, as recently as 2003. At the time, the US extensively enforced the ROK–U.S. Mutual Defense Treaty to strengthen its overseas defense force, and it has since been relocating its military bases on the Korean Peninsula. Here, another charred memory emerges: two 14-year-old girls, Shin Hyo-sun and Sim Mi-seon, were struck and run over to death by a US military armored vehicle on a country road in Yangju, Gyeonggi-do, in 2002, the year before the strict enforcement of the Mutual Defense Treaty. Koreans had been cheering for the World Cup and only later learned of the incident. Their grief and horror were indescribable. The more people dug into this issue, the more lasting scars of modern Korean history were unearthed. Combining what has already been buried with whatever has been thrown away creates a uniformity that does not mix. From the black soil of the US military base to the US-ROK political history and its resulting social traumas, the scene depicted in Bang Jeong-A’s work reveals a helpless, awkward aesthetic of real-life politics that rests between the anxious and the ominous.

Whatever Reality

(1) The Realism of Bang Jeong-A

In the early 1990s, when Bang Jeong-A started her career, Korea began to embrace an economic system of global neoliberalism centered on the United States. Consumerism and mammonism were prevalent across all strata of society. The results of the Uruguay Round agreement pressured Korea to lift import restrictions on rice from 1992, and the IMF crisis of 1997 led to a collapse of small businesses across the nation. During this process, Korea made a rapid shift to American neoliberalism, and the personal lives of citizens underwent an abrupt change. Foreign loans borrowed to finance the establishment of a modern state became national debt that eventually led to corporate and household debt, a situation that could have catastrophic consequences for the nation and all parties involved.1 Not foreseeing a future of financial liability, Korean society appeared unshackled between the late 1980s and the mid-1990s. As censors lifted and cash circulation soared, a desire to enjoy this newfound freedom consumed urban areas. A new Gangnam generation was thus born, alongside a less than average “loser” generation, drowning in debt as depicted in the 2021 TV show Squid Game.2

During this time, Bang Jeong-A painted urban women of the lower working class. There was no choice in the matter, for she felt the need to paint the invisibility of those omnipresent in yet largely ignored by society. In her paintings, we see factory girls waiting for the morning bus on their way to work, an older woman cleaning her bruised body in the bathhouse near closing time, and a mother eating a skewer of fishcake while carrying on her back a child sucking its thumb. Women Waiting for Early Bus in Guro Industrial Complex (1971) and Women standing on the edge of the sea (1993) are oil paintings rendered in a realist style that serve as examples, along with the acrylic paintings, A rushing bath (1994) and A women who ran away from home (1996), that present a sense of instantaneity. The figures’ facial expressions and postures suggest their suffering to be rather impossible to be duly explained but spelled out as-is in minute detail.

The paintings He Had a Grudge Against His Unfaithful Girlfriend Who Was Living With Him And… (2001) and What Made Her Life So Miserable? (2002) share a diagonal composition often seen in that of snapshots, which can also be observed in A rushing bath and A women who ran away from home. Both works depict an unclear situation, but space captured in blue at a downwards angle is a labyrinth their lives have fallen into. A “momentary” lapse in judgment and “in-the-moment” decisions, much like snapshots, capture a single “moment” of a much more complex affair. This sense of instantaneity underscores the disconsolation of these situations, stuck in labyrinths. The man’s head, stumped down onto the desk, must be in tangles that are as complicated as the wires connected to his computer. The woman may be well dressed in a warm sweater, shiny heels, and a glossy hairdo, yet the question of why she’s lying in the bathroom will remain forever unanswered. Bang Jeong-A stresses that “communication” is a societal rather than a subjective function. Decent communication depends on the provided network infrastructure and the understanding of society as a whole. Despite its unrestrained climate and rapidly developing network devices, Korean society of the time was stuck in a labyrinth that only got deeper with time, cut off from communication.

Truth be told, the lives of the urban poor are hard to visualize and can only be suspect. Thus, their stories remain veiled. Only their suffering spreads like smoke through vague, stale rumors, permeating the corners of everyday life. But a life of suffering is not unique. It is prevalent in any city corner yet noted only when certain incidents shed light on their circumstances. Even then, these lives are consumed as a type of isolated personal gossip and are not given the attention needed on a socio-structural level. In the process, social unhappiness and personal distress turn everyday life into a labyrinth of questions. Bang Jeong-A understands that the frustration and limitations that arise in social communication are the faults not of an individual but of the system. The apparatus or dispositif is a horrible, infinite cycle of ignorance and indifference to the apparent social reality, media politics that facilitate consuming spectacles, and the harsh lives people lead in a dog-eat-dog world. Naturally, the theme and critical mindset behind these works align with the realism of the 1980s Minjung art movement. Bang Jeong-A takes a step forward, however, focusing on new apparatus and methods of reproducing reality. Because reality exists for everybody and anybody, it speaks to a “whatever singularity.”3 Along with actuality, reality has been revealed in the refrain (Ritornello). The issues that arise from the fissure between reality and reproduction—such as ignorance and tyranny, power and politics, and lust and humanity—are composed of “the real” or things considered “real.” In this sense, communication in Korean society was far from realistic but merely walked the line between all kinds of truths that surrounded the real. Is it possible to reproduce reality? As can be observed in realist works from the 1980s, reality was not something that could be restructured or reproduced but was, instead, felt. The First Manifesto of the Reality Group, highly influential to the realist movement of the 1980s, is one example that shows the heavy emphasis on producing a detailed, vital expression of reality and its subject that brought upon an acute sense of perception. It came to the point where the terms “realist vitalism” or “vital realism” were adopted.4 How does reality reveal itself in Bang Jeong-A’s paintings, then? It does so by making an abrupt appearance, like a scene from an incident. The listless subjects may be actual figures in real life, but reality’s vitality is tangible only in the pictorial device that is the painting. Their shame, suffering, despondence, and dead-end hopelessness are implied only through the said pictorial device. In Bang Jeong-A’s paintings, the sense of reality is stuck somewhere in a crooked time-space along the curved backs, reluctant facial expressions, meandering lines, and winding hues.

At the time, a culture of spectacles indeed consumed Korean society. There was a fervent need for show. The realities of ordinary suffering and microaggression were no exception to such a culture of consumption. And so, the reality could not be reproduced; it was merely a version of manipulated actuality or an indirect evocation. The figures portrayed in Bang Jeong-A’s paintings are results of subordination who could not escape the apparatus of visibility. In a sense, these paintings archive the disappearance of moments the Korean society wants to hide or turn a blind eye to. Now, reality becomes a hiding ground for truth.

(2) The Indivisible Divide

It is in Before Life Begins (2002) that Bang Jeong-A began to develop an aesthetic of ambivalence and scattered fragmentation through painterly brush strokes and lines. The artist depicts the living organisms and trash thrown alongside a pathway in the same manner of squiggly, mushy lines, much like hair blowing in the wind. They seem both dying and coming back alive. Thus, with painted lines, Bang Jeong-A managed to harmoniously assemble the deceased, trashed, and newly sprouted shoots. As seen in The Slippery Reveal (2005) and Natural Death (2008), Bang Jeong-A tends to blur the distinctions between elements of nature, such as the sea, water, watergrass, twigs, and forests, by employing meandering strokes that run soft and mushy. In this manner, her paintings evolve from capturing episodic scenes to forming narratives of more complexity. In other words, Bang Jeong-A during the 2000s can be said to have experimented with a variety of brush strokes, strengthening her painterly expression and putting forth a sense of vitality grounded in the present moment. The themes of her paintings also materialize more clearly, especially in the multilayeredness of various relationships, such as those between humanity and society, nature, the atmosphere, physical matter, and landscapes. With these expressive factors comes forth a richer narrative.

Starting from 2011, we see a strengthening of irony, ambivalence, and suspense in Bang Jeong-A’s works. Take for example, forest 1,2 (2011). Despite the artificiality of manmade nature and the disabled human, the “forest” exudes an aura of nature’s sylvan majesty. The subtle ominousness of artificial nature later merges with the suspicious elements in Bang Jeong-A’s paintings. Note the difference between Split (2010) and Siamese Twins (2012); in lieu of realistic expressions, flatness and line strokes are emphasized. This contributes to strengthening the expression of inseparable fragmentation, as observed in Bombing(Optical illusion) (2018). The pictorial elements that break down the boundaries between the subject and its surroundings, while expressing inseparable fragmentation, introduce to the narrative not only an ambivalent temporality, but also a subtle and highly complex aesthetic of anxiety. This is based on an interrelationship of treachery or irony that blends into their surroundings in an independent but scattered, or dissipating, manner. Observe 70 Years of Rough Life (2018) and Person Bound to the Past (2018). The aesthetic of anxiety that has its foundations on such independence and dissipation is also evident in the present image of those who devoted themselves to national security and economic development during the era of Korea’s military dictatorship. This is the face of anxiety, of a life fragmented before reaching its full potential.

Disasters that occurred in metropolitan cities, such as the September 11 attacks in 2001 and the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in 2011, became instrumental in forming the political capital of global unrest and foretold an era of post-truth and aloof politics. In a political competition over telling the truth, truth itself became a distant myth, and what touched the lives of the people and shook the foundation of their daily lives was, ironically, fake news and urban legend. The emotionally far-reaching impact of gossip easily swallowed people, and such instigations misled even official media channels. Stories akin to gossip and snapshots turned the whole world into a furnace of doubt, and as this global competition for truth intensified, the level of truth ran paler in hue. In this era of globalization, power is restructured not through an exceptional state of war but through a state of truth as a void. Even in Korea, urban legends surrounding Fukushima and detailed facts touted as scientific evidence were pitted against each other. Bang Jeong-A once again stood witness to the irony of a society swept up in a game of truth and lies. Unlike before, however, she could not paint mere snapshots. Sometime around 2016, she began researching the current status of Korea’s nuclear power plants. After exploring the sites in person, she painted the irony of visibility in the Korean government’s policies: its politics of spectacle that implicitly pulls the wool over eyes with a showy facade. As such, Bang Jeong-A focused intently on “invisibility.” Non-visibility was a significant part of history and the core of Korea’s modernization project. In this fashion, Bang Jeong-A took nuclear power and the divided peninsula at the core of Korea’s developmental modernization as the primary focus of this exhibition.

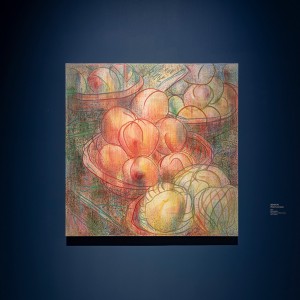

twelve domes (2018) is a pastel work showcased at the 2018 Gwangju Biennale, which portrayed the political situation in Korea as a satire. The rounded outlines of the nuclear power plants and the burial mounds at the foot of the hill give shape to twelve rounded forms, as described in the work’s title. A large crowd rises and falls with the ocean’s waves at the center of the picture, where life and death divide. In Moment When She Raised Her Hand (2019), the artist comprehensively arranged made-present sentiments that had germinated in modern Korean history. Koreans of all shapes and sizes—the president, other politicians, veterans, artists, ordinary people—appear in the picture, which is forcibly divided by the red pillars. And from its partitions emerge suspicion, doubt, ominousness, indifference, nonchalance, shamelessness, ignorance, ambiguity, hesitation, and incompetence. Satiric ironies and sangfroid that weigh heavy on the heart are also present in the artist’s depictions of the most mundane of scenes. In the homonymously titled It’s on display. But (2021), both war and exhibition are in full swing. Among the people in charge, busy on their cell phones, are lined-up torsos in the nude. Missing their heads and limbs, these torsos are bodies, in fact, severed from the very appendages required for sensing or laboring. The clenched fists of the artist signify the state’s urgency and frustrations.

(3) “Heumul-heumul” (Liquid Scenery)

Take, for example, the homogeneous city, formed in a composite of cement and asphalt and the dimension called truth that will forever remain unveiled in media overrun with gossip and rumors. Bang Jeong-A imbues with a raw vividness these sites of agnosticism (agnostic sites) in her paintings. Everyday life becomes likened to a site where soil is seeped into and penetrated by water, but only by hypothetical truth, doubt, and anxiety. Thus, Bang Jeong-A’s painterly expressions embody a wavering, swaying fluidity. All of the narrative elements in the painting connect and blend into one another, creating an optical illusion. Although volatile, unpredictable, and uncertain, the illusion resembles nature in its everlasting perpetuity.

The theme of the exhibition, “heumul-heumul,” is an expression that touches upon the two aspects of liquidity: one a dystopian reality in the style of Zygmunt Bauman dubbed “liquid modernity,” the other the “vibrant reality” of Jane Bennett, who spoke of the vitality in materials.5 Bang Jeong-A’s paintings evoke reality through the apparatus of reproduction and express reality itself as “vibrant affect.” Namely, the affect itself expressed by Bang Jeong-A is one “heumul-heumul,” meaning in Korean soft and mushy. This state of mixture and agitation we call “lively reality” materializes in A Plastic Ecosystem (2021). The area that presents the large banner painting is a space of plasticity. The depicted chrysanthemums are the aesthetic expression of plasticity, unclear whether they are withering away or raising their heads like zombies. On the floor are chairs, objects that symbolize the fuel rods stored away in nuclear power plants. The gallery space takes on a hint of science fiction but reflects our reality. Reality is a type of void in Bang Jeong-A’s work. The subjects of truth or the truth itself are the ones that create the void or become it. The void is the cause and pivotal point of the cycle of a destructive infinity. The dystopia of undecaying modernity and the vitality of nature in the cycle expressed in this space also characterize Korea’s modernity.

Bang Jeong-A captures a time in history in a state soft and mushy. In America, his unwavering attitude (2021), Bang Jeong-A paints four gods, one as an older man and three as a young woman. The man’s wrinkled body leans against a fountain in only his underwear, exposing most of his body to the elements. He is as limp as the water that runs down the fountain yet manages to hold the attention of three women. On the left, a woman in a dress stands tall with a cellphone in her hand. Side-eying the man, as would an undercover cop, she acts as the recorder and archivist. She happens to be where the truth stands in current times, disguised in mundanity. While her cellphone records, she heightens her visual senses and focuses on storing the influx of information in her “nonconscious” as memory. She will eventually become a testifier of the truth, recalling the images imprinted in her brain that may be more reliable than those left behind in a cellphone. Although her memories will eventually fade, she will still have access to what is stored in her “nonconscious.” Another woman is restless in her hips as she approaches the man. It is unclear whether she will attack or help him, and we will get to see only her face after she commits either act. Her stories told after the act, no matter how critical the situation, will hold no power as testimony. While leaning towards the audience as she moves away from the center of attention, the third woman continues to be suspicious of the situation. She is practicing doubt, the most rational human activity. Her rationality, eventually, will lead her to flee the scene.

This painting is about time, truth (or its subject), and the vicious infinite cycle surrounding them. Records and (nonconscious) memories, unrest and displacement, as well as doubt, are all components of truth. However, the advanced artificial device we call modern politics makes false gestures, creating a well of truth out of a void. The competition to seize the truth as one’s own creates power, and the violence committed in the process is justified. The truth becomes a ritornello that is either born alongside or breaks free with power. An awakened, clear conscience is merely a facet of the situation. No matter how just the truth wants to be, it can never be. In this sense, justice might be but a humanistic phenomenon revealed from time to time by engaging in complex fragmentation and convocation.

Painting in a Climate of Anxiety

Bang Jeong-A has long painted the landscape of daily life in Korean society. These landscapes also happen to be part of contemporary Korean history, born of post-division politics. It is not a landscape of contemplation but more a narrative space full of irony, ambivalence, and complex but unspeakable stories, one that continues to deliver the more we dig. From this, Bang Jeong-A constructs her own unique pictorial narrative between reality itself and a socially and politically fabricated narrative. MacGuffins are something she often uses. A particular figure, posture, expression, or object that seems commonplace yet out of the ordinary piques our curiosity. And the closer we examine Bang’s works, it is clear that every component had been placed for a reason. In this mode of accidental precision are evocations of cinematic suspense, humor, sensory materiality, and nature.

Of course, reexamining the depth of aesthetic criticism in contemporary art is a characteristic of artists hailing from a post-realism or post-truth generation, who mainly work in the realms of conceptual and critical realism. The prefix “post-” does not quite fit Bang Jeong-A’s tension, however. Much like reality in a constant state of tension, not as a ritornello to actuality but as reality itself, truth is neither a tool to fabricate the existence of what never existed nor an obsession that needs establishment. As if to express the issues of reality and truth via tension and competence, Bang Jeong-A builds a painterliness that manages to encompass and deliver complex narratives with the facets of the organic and inorganic.

If her early works critiqued the breakdown in communication, Bang Jeong-A during the 2010s explored another potential aspect of communication: temporality. The opportunity presented itself in the reality of Korea and its presentness of now. Especially since the 2000s, Bang searched for a way to escape the repeated, vicious cycle in Korean society and politics. Her interest also happened to become an inspection of and reflection on the limitations of anthropocentrism and humanity. What Bang discovered was time. Wedged between historical and geological time was a temporal concept of “the wait,” whose discovery is well documented in her work Return (2002). In the background is a frighteningly fantastic ocean. At its center in the far distance, the outline of a woman carrying a child comes into view. Mother and daughter are headed towards the ocean and its endless horizon, not a steamy, cozy vendor hawing fish skewers. In the back is a scene of haphazard digging, with steel bars and cement lying ugly on the ground; it’s the first thing the viewers see clearly. The mother and child stand precarious in the center, heading towards a beautiful but fearsome sea. Through the exhibition’s theme of “heumul-heumul,” Bang Jeong-A unravels concerns she has been musing on in recent years regarding the true nature of the Korean reality and the Earth’s environment. In A Plastic Ecosystem, she combines the temporality of history with the presentness of now by utilizing the aesthetics of visibility. In paintings such as America, his unwavering attitude, I dug, and it came out, It’s on display. But, and Congratulations on your new business, she uses the aesthetics of liquidity to reveal Korea and its politics, its people, and the land on which they vie for dominance.

Bang Jeong-A refuses to focus her contemplation on nature because nature happens to be a part of reality. The artist is enraged at the violations and damage unleashed upon our land, water, and life. Nonetheless, Bang Jeong-A’s paintings present scenes of inseparable fragmentation on account of the hope she pins on the ambivalence of life. Emotions of doubt and anxiety are also of ambivalent affect, sentiments alive and breathing. Plasticity and liquidity are the vitalized abilities of land and water, although they also reflect the facets of human society living in this environment. Bang’s paintings—as a scene of affects that soar high and deep, traverses and intersects—are a landscape of the anxious climate we call reality. The affects covered in the field of aesthetics reveal a different dimension of time. It is a universal time that runs slowly, almost stationary, yet eternal.

1 On topics of neoliberalism, Korean politics, and analysis of debt economy, the following works were referenced: Chan-jong Park, “The Political Origin of Neoliberalism in Korea: Economic Policy Shift After the Busan-Masan and the Gwangju Protest Movements,” Society & History, vol. 117 (March, 2018), 79–120; Chan-jong Park, “The Structural Change of Debt-Economy in Korea: From Corporate Debt to Household Debt,” Oughtopia, vol. 33, No. 2 (August, 2018), 75–113.

2 A Netflix Original Series by director Hwang Dong-hyuk.

3 “Whatever singularity” is a term developed by Giorgio Agamben. The writer applied this concept to “reality” to call it “whatever reality.” The following book was referenced: Giorgio Agamben, The Coming Community, trans. Michael Hardt (Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, sixth printing, 2007).

4 The 1969 Manifesto of Reality Group, First Manifesto of the Reality Group, was reissued in the exhibition database archive Locus and Focus (2020, pp. 24–65) by Gyeonggi Museum of Modern Art.

5 Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things, trans. Sung-jae Moon (Seoul: Hyunsilmunhwa, 2020); Zygmunt Bauman, Liquid Modernity (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2000). If Bauman makes a vivid criticism of capitalism, Bennett goes as far as to analyze materiality from the perspective of vitality, bringing to light the more intricate importance of modern politics.

Critic 3

Nothing Happens

Yang Jungae (independent curator)

Bottomless

I think of terrifying windmill adventures, adventures I’ve never even imagined1. I mean the adventures of Don Quixote: reckless, he did not heed the word that those he wanted to fight were by no means giants, only windmills, and had to charge ever closer to realize it properly. Bang Jeong-A spent her youth in the late 1980s, during the oppressive years of contemporary Korean history held up by the pillars of sociopolitical ideology. What did those pillars mean to her?2 In the final days of the so-called Minjung art movement, the artist had returned to Busan to find her own way to engage with society through art. It became unthinkable for her to detach her hometown from herself, as Busan became the setting of her artistic endeavors. Dubbed Korea’s second city, Busan is renowned as a cultural hotspot and tourist attraction, bolstered by its own international film festivals and art biennales. But to Bang Jeong-A, it is also a microcosm of Korea’s complex modern and contemporary history, as well as a port city where military supplies and test specimens of bacteria flow in, and a city where a nuclear power plant is holding out. The belief that the collapse of an unyielding vertical system would bring about a horizontal world was disproved by the experience of moments when her daily life still wavered. Through that experience, the artist became keenly aware of the utterly natural and seemingly familiar contemporary landscape around her.

She intuitively realized that the ground she had expected to be firm was really just a buoy, barely supporting her two feet, and she began to discover the unnaturalness of the everyday that had hitherto seemed so natural. Things that should not ever shatter were melting away, while nothing happened to things so rigid that were to be demolished. Bang Jeong-A is an artist who has lived through a society that has, with increasing entropy, evolved — like plastic melting when external pressure is applied — from a solid society into a liquid one. She captures what she perceives as “bothersome” scenes of daily life in her paintings, such as Korean Political Landscape and A Plastic Ecosystem. In this exhibition, the artist employs painting as her medium to put on display the signs of our everyday anxieties: signs covered in nature-made-artificially, deceptive of their inherent dangers, and lulling away people’s fears. She makes the public facing her art intervene and dig into the stories hidden behind the artwork. Though it began with the stories of the specific place of Busan, Bang Jeong-A’s works ultimately convey that these stories are universal in the realm of humankind, not specific to one locale.

Bothersome

The recent US withdrawal from Afghanistan appeared to overlap in many ways with the problematic anthrax tests the US armed forces (USFK) conducted in Korea a few years ago. From the rooftop of her studio in Jwacheon-dong, Busan, Bang Jeong-A could see the stern of the warship docked at the US military base in Pier 8 of Busan Port. She used to imagine the sight of exploding anthrax soaring straight up and reaching her. While that scene remains imaginary for now, stranger things have been known to happen. In fact, it was revealed in 2015 that live anthrax samples had been shipped to Korea without due notice. Since then, the name of the “JUPITR project”3 became known to the public, and it was confirmed that bacterial experiments had actually been undertaken at Pier 8 , in the very heart of the city. Shockingly, however, nothing was done in response to this revelation. On the contrary, JUPITR changed its name to CENTAUR, then to IEW, and conducted more-advanced experiments. America, his unwavering attitude looks squarely at how the United States is still taking advantage of the “ROK–U.S. Mutual Defense Treaty,” whose legitimacy is fading in the liquidating international order, and how the blocking of information is hindering the expression of anger and frustration. As such, the work presents and reinterprets a facet of Busan, which has turned into an extraterritorial biochemical laboratory for the US military. In the center of the painting, an aged man sits by a fountain, wearing nothing but underwear and a military backpack. The three young women around him are either looking at him uncomfortably or trying to ignore him altogether. The moment the viewer recognizes the man as Jupiter, a mythological god, the women turn into the three Graces, and their occupied space into a temple supported by solid vertical columns. However, when we recognize the space where the old man is sitting as a seokgasan, an artificial mountain of stacked stones often installed in apartment complexes, the scene is immediately deprived of its mythical authority. As “Jupiter” becomes a stranger invading our everyday life, so are our “three Graces” rediscovered as ordinary Busan women. Only these “women” remind us of the ridiculousness of “Jupiter,” as ridiculous as the fairytale emperor in his “new clothes.” This “naked Jupiter” symbolizes the US in the essence and attitude of a great power that amassed its strengths from the solid age of neo-imperialism to the Cold War. It is a two-faced attitude that most times promotes the seemingly harmless values of democracy, human rights, and peace but in reality neglects other countries’ human rights. There is also ambivalence in our own attitude towards the US. The figure in the distance, wearing a sun hat and resting absentmindedly, or the figure enjoying his feet in the water and absorbed by his phone, exhibits indifference as if the state of things were just a matter of course. It reads as an attitude of still wanting to be protected even when there is no longer a need to depend upon the US, or of maintaining indifference in a liquid environment where a clear-cut basis for judgment has disappeared.

Bang Jeong-A puts at the center a Western-style artificial fountain surrounding the everyday object of seokgasan, modeled after “Jingyeong Sansu,” a 17th-century Korean art movement of painting actual mountains and landscapes rather than imaginary ones. This juxtaposition of incompatible heterogeneous elements in the same time and space builds tension. The continued array of contrasting imagery, such as old age and youth, man and woman, pillars and water, and artificiality and nature, invites the viewer to sense our current society and the power relations in a world order that has changed over the past hundred-odd years. Through these aesthetic devices, the artist reveals the “superficial” serenity in the world order created by the so-called great powers and the callous exploitation of its “other side.” She points out the sympathies of an unfamiliar mythicized moment turned into everyday life by “Jupiter,” sitting there without inhibition, thereby revealing inherent antipathy.

I dug, and it came out. (2021) deals with the grave issue surrounding waste oil and contaminated soil left behind in the Busan Citizens Park, formerly known as Camp Hialeah, that stationed US forces, near the artist’s house. Bang Jeong-A became uneasy as contaminated soil continued to be unearthed, despite the statements claiming to have purified the contamination such as carcinogens. The land was not adequately healed but was covered up, and Bang envisions the fear of what this will bring as an unpredictable, ominous being wrapped in red cloth. A woman sitting on a park bench wears a mask as people do in a pandemic, so the viewer understands the scene to be in the here and now. As she faces the figure, her expression is neither visibly surprised nor completely indifferent. Just as we came to accept mask-wearing as a natural part of daily life, we have become insensitive to an overtly unrealistic being. While the woman on the bench is an “eyewitness” to a strange being, such an identity can be interpreted in various ways. If the next moment calls for action, she may become a prospective victim unable to recognize danger, an inevitable bystander, a conspirator in a cover-up, or even a resisting person. When the laid-back spatial context meets the “misaligned gaze” — a state of ignoring a staring gaze — between the woman and the unidentified figure, the viewer shares the artist’s frightful experience of the “open complicity stemming from indifference” or the reticent “otherness” prevalent in the space of coexistence.

All human and non-human actors appearing in this work are interconnected, each to their own role. The soil contamination perpetrated by the US military for the past several decades, the authorities who covered up the fact with paving blocks and benches, and an unidentified mass of people carrying on their present-day lives while burdened with anxiety about such facts compactly appear in a multi-layered space and time, creating a complex narrative. Nowhere is there any show-and-tell of the dug-up contaminated soil. But what can be seen is a well-covered state of affairs. The painting’s toned-down colors make it challenging to tell whether the scene has been taken from real life or not. By boldly choosing to paint a less compelling spectacle, an inefficient way to attract viewers, Bang Jeong-A draws the curious and turns them into active participants.

Congratulations on your new business (2021) captures the sentiment surrounding the uneasy armistice that persists despite gestures of reconciliation during the Inter-Korean Summit. The work’s title expresses the irony of a situation in which relations between the two Koreas can progress only if the United States allows the UN and North Korea to declare the war’s end. After watching news reports of the two Korean leaders on the footbridge at Panmunjeom discussing the agenda of “Peace, a New Future” in 2018, Bang Jeong-A painted Spread voice (2018) [Figure 1]. The painting recorded the momentary excitement at softened inter-Korean relations back then; today, however, the artist faces the desolation of empty chairs, with people and voices gone.

Congratulations on your new business is a work that shows very well how Bang Jeong-A contextualizes a location while simultaneously erasing its context. From the artist’s point of view, the demilitarized zone (DMZ) that serves as the stage in this work is the only non-rigid ecosystem left on the Korean peninsula. However, it is also a space that can, if touched incorrectly, harden at any moment. By assigning the ambiguous role of the geopolitical agenda for the demilitarized zone to the objects in the painting, the artist effortlessly dissolves into it our society’s ambivalence towards the US and what it stands for. Wavering lines capture the moment the two politicians leave, having sat down and chatted only a while ago. While the red and blue plastic chairs recall the moment when the two were close enough to touch, they also imply their potential return, coming back to sit down again soon. The title, Congratulations on your new business, also reads differently, depending on who is assumed to have sent the wreath. Should the US have sent it, that implies the irresponsibility and neglect of not making an actual appearance while seeming to celebrate the thaw in relations. It is also a message from the artist, hopeful for future improvement despite the current state of affairs. The giant wreaths of artificial flowers, with the wild and rough pine trees, obscure the barbed wire, making the demilitarized zone seem as familiar as any old neighborhood hill; this speaks for the complex feelings of Koreans, for whom such a future seems plausible yet still obscure. Therefore, this space transforms into a place where a no longer existing desired ideal is reproduced in our reality or where the intention to topple over the state of affairs, previously unreachable by will, is revealed.

[Figure 1] Bang Jeong-A, Spread voice, 2018, oil pastel on fabric, 91×116.8cm.

As in Congratulations on your new business, the powerlessness of being stuck in the armistice agreement, hindering our ability to solve our problems independently, continues in It’s on display. But (2021). A gallery space serves as the painting’s background, in which are torsos on display, missing parts of or whole arms and legs. Two women in the foreground are on their phones, each busy conducting her own business. The viewer can imagine a phone call inquiring about the exhibition, to which the women answer, “It’s on display. But….” As may be guessed, the title is the artist’s play on homonyms that signify being “on display” and “at war” because literally, the Korean War is still ongoing. The exquisite combination of text and image that reveals insight into such a state of affairs may be called a revival of a linguistic-locational, or linguistic-temporal, mode of expression that, as frequently witnessed in Bang’s previous work, creates tension and even rupture in the time and space of the painting.

Although they seem unimportant to the work’s apparent theme, Bang Jeong-A draws the viewer’s attention to the two women’s facial expressions, gestures, and phones in their hands. The torsos, comparatively more revealing of the work’s actual theme, are pushed into the background. Their placement makes it further challenging for the viewer to recognize the North and South Korean military uniforms thrown on them. Scattering the torsos left and right of a pillar reflects the tangled form in which Korea’s neighbors stand idly by, each with its own interest, leaving the two Koreas in a volatile state between them, unable to act as they would like. In reality, however, we lead our daily lives, unaware of our state in which, at any time, hostilities could break out to no surprise. In fact, It’s on display. But captures a scene that actually took place while the artist was preparing for the Korea Artist Prize 2021 exhibition. Other artists came to help but got preoccupied and neglected the work, leaving the artist clenching her fists in anger and frustration. What is the artist’s intention in suddenly transforming a scene entrenched in a sociopolitical topic into one from her own working environment? May it not be that to Bang Jeong-A, the real crisis was our internalized insensitivity to war, leaving us unable to perceive a crisis as a crisis? Thus, in making her work feel uncanny, the artist beckons her audience to see the painting itself as a result of the same uncanniness. That is, by intentionally revealing herself on a large canvas and foregrounding the actual situation of which she was a part, Bang Jeong-A quite naturally incorporates perhaps indifferent viewers into the artist’s here and now. In doing so, she urges them to share each other’s experiences and perspectives about our situation “at war,” reckoning that all of us, in fact, “dream different dreams in the same bed.”

Melting

The exhibition’s second section presents A Plastic Ecosystem (2021), which renders a nuclear power plant and ecosystem melting, like plastic, from the unstoppable, infinite heat it generates. The existence of a nuclear power plant within 30 km of the artist’s Busan studio, jumbled with the vivid and unforgettable memory of the meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, threatens the artist’s everyday life. Since 2016, Bang Jeong-A has, together with fellow artists, informed the public of the dangers of nuclear power plants,4and in a narrow sense, A Plastic Ecosystem can be seen as an extension of those activities. In her previous works Not on the map (2019) and Dome’s Secret (2019) [Figure 2], the artist presented a journey to a place that certainly exists but not on a map, or a location that exists only when one searches for its “public information center.” The moment people believe they have found utopia in virtual reality (VR), they realize it is, in fact, an “inverse” “utopia.” The nuclear power plant, often ideally packaged, is doomed to exist permanently. As such, it cannot become a heterotopia, a utopia “temporarily realized.” Therefore, the artist attempts to subvert the utopian myth by paradoxically creating a place of hybridity in her artwork.

A Plastic Ecosystem shows the hidden side of nuclear power plants entangled with figures and bodies of power by arranging heterogeneous, clashing objects in one space. This particular space manifests parts of what is seen in Dome’s Secret, which transposes the virtual space depicted in the painting into a real, three-dimensional gallery space in a museum. Thus A Plastic Ecosystem is displayed in a space set as a nuclear power plant’s cooling tank. There, the viewer follows the dynamics of the display and participates unknowingly in an act perceived by the artist5. As the viewer enters a blue-painted space and sits on the chairs to see the artist’s works, they are unaware of having stepped into a nuclear reactor, relaxing on nuclear fuel rods generating heat from fission of uranium, and watching the ecosystem, like distorted and thrown-away plastic, melt away in a tank that is supposed to cool down those same fuel rods. All of these components are, to borrow the words of the artist, “like time bombs emitting radiation for tens of thousands of years, which we want to avoid and keep completely secret. We do not even realize we are sitting on nuclear fuel rods if we do not take a closer look; this is the current reality.”

[Figure 2] Bang Jeong-A, Dome’s Secret, still cut from VR animation, 2019.

An enormous drape of fabric, stitched together from smaller fabric pieces of differing weights, materials, and sizes, tumbles down from the ceiling. A Plastic Ecosystem is made to look like an ecosystem melting down after enduring a mass of materials discarded from a carnival that we call our modern consumer society. The uneven cut of the fabrics creates a somewhat volatile tension in the white cube gallery space. This massive hanging picture, painted with acrylic on stitched-together cotton sheets, is a tribute to textiles produced during the 1980s that were used until they were in tatters, moved here and there, folded, dried, and patched. In displaying such work within an institution like a museum, the artist attempts to reproduce the public square, a ceremonial space made temporarily sublime by hanging pictures. The artist actively employs all of the white cube gallery space’s usual devices to give the work a ceremonious character; the space, lighting, and displayed objects, among other elements, manipulate the viewer’s movement within it. And when the viewer navigates this ceremonial space made and occupied by the hanging picture, they face its uneven patchwork. The stools, resembling spent fuel rods that have reached the end of their use, are made of waste from the museum’s past exhibitions, which the artist collected and drew and painted on onsite. For some visitors the stools are untouchable parts of the artwork, exuding their own artistic aura, while for others they are logical places to sit and relax. As such, the artist has arranged the gallery space so that viewers find themselves intervening in her works, hoping to prompt them to actions of their own. Since a perfect reproduction of reality is impossible, viewers may think to themselves, “What kind of a nuclear fuel rod looks like this?” They may then use their smartphones to search for a real-life example by the time they leave the exhibition, which is the artist’s suggested way of taking a step closer to our reality.

Penetrating

I had the opportunity to observe Bang Jeong-A engaged in the nuclear disarmament movement for quite some time (2016–2020). She researched nuclear power plants in person and recorded the actions of fellow artists so their efforts would not dissolve after being exhibited. One day she emailed visitors to one exhibition, attaching a file that faithfully archived every means to their work and asking them for their continued interest and support. Though fully aware of Bang’s oeuvre, which has developed beyond two-dimensional paintings from her work as an activist — I have seen her perform on a shore next to a nuclear power plant and produce a “nuclear disarmament pocketbook” — I was still concerned about the limitations that artists inevitably face when their social engagement takes place in a liquid society. Perhaps the exhibition might be seen as Bang Jeong-A’s way of answering the question.

Bang Jeong-A constantly tackles ongoing social issues and conveys them in present progressive form. That is to say, though she knows that the artwork will be damaged after being displayed for a certain time, watching the process of its tattering might be the final destination of A Plastic Ecosystem. The viewers, having passed through this space, will come to share, to a certain extent, the artist’s “bothered” feelings. This reflects on her work as an artist, turning a multi-layered social problem into an aesthetic object while at the same time positioning her work as a medium for a public dialogue about society. The phrase that she is in the habit of adding after describing something to be “bothersome” is “so what?” I think the artist’s attitude of showing through her work the impossibility of this goal — keeping at it and hoping something will happen, even though knowing nothing will come of it — can indeed be a form of reflective resistance.

Bang Jeong-A’s works float around, constantly exploring the cracks among various stories. Once the text is hidden, the works change their meaning in the context of the viewer. Heterogeneous actors, unable to distinguish between human and non-human actors constituting the space and the moment of the artwork, are loosely connected. They look in different directions, conveying narratives slightly disjointed. The exhibition Heumul-heumul, which denotes a soft and mushy state, is divided into two sections, each with a different theme. The artist, however, planted devices to allow complex interpretations that can reach across those two themes. Focusing on the bonsai or the seokgasan depicted in America, his unwavering attitude, we find the irony of human attempts to perfect their craft of creating an artificial nature while destroying the real one. If, in Congratulations on your new business, the focus is on the wreaths or the plastic chairs used and thrown away after a temporary event, we can sense criticism from an ecological point of view. From a bird’s-eye view, Bang’s oeuvre can be understood to present the “opposition between civilization and nature.” In this way, the artist leaves her works open to interpretation, refusing to confine them to a certain narrative, so the public can, through her work, participate in cracking and penetrating all rigid things.

Visual images, in whatever form, provide a powerful impetus for direct action the moment they gain symbolic power. Referring to the worldwide impact of the 2011 tsunami, film director and artist Trin T. Minh-ha mentioned that, more than from the sight of the colossal waves, a tremendous shock came from the fleeting image of a dog, tied on a leash, facing the surging tsunami.6 Symbolism is not guaranteed by spectacle; instead, it is gained through details that satisfy a specific cultural or situational context. Bang Jeong-A’s works aggregate minor images around us, such as benches, fountains, mannequins, and plastic chairs. They connect those images loosely, by covering or insufficiently showing the parts that must be shown while putting to the fore what really should not be. In so doing, they leave cracks that other people can penetrate, each with a perspective of their own. Through the works in the exhibition, Bang Jeong-A shows that the countless points of contact, created in sync by the artworks and by everyone’s context, are made possible by the heterogeneity of seemingly insignificant images. And the moment these connections take place, they lead the viewer to reflection and self-cultivation, driving even greater resistance.