Jo Haejun

Interview

CV

2013

Joh Hae Jun Solo exhibition, Woojin Culture Foundation, Jeonju, Korea

2008

Jo Family Chronicle, Art Space Pool, Seoul, KR

2005

The Pioneer’s Visit, Ssamzie Space, Seoul, KR

<Selected Group Exhibitions>

2014

Ghost, Spies, and Grandmothers, Media City Seoul 2014, Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea

2013

The First Encounter, The Beginning of ‘Empty Friendship’, Incheon Platform, Incheon, Korea

Root of Relation, Shong Zhuang Art Center, Beijing, China

Freedom, Kunstpalais, Erlangen, DE

2012

INTERVIEW, Heidelberger Kunstverein, Heidelberg, DE

2011

Korean Rhapsody – Crossing the History, Leeum Samsung Museum of Art, Seoul, KR

Drawing in Relation, DNA Galerie, Berlin, DE

2010

Biennale Cuvee, OK Center for Contemporary Art, Linz, AT

2009

Antrepo-3, 11th Istanbul Biennale, Istanbul, TR

MADE IN KOREA: LEISURE, ADISGUISELABOR, KaufhausSinn & Leffers, Hanover, DE

Another Masterpiece – New Acquisitions, Gyeonggi Museum of Modern Art, Ansan, KR

BAD BOYS HERE AND NOW: NEW POLITICAL ART IN KOREA SINCE THE 1990s, Gyeonggi Museum of Modern Art, Ansan, KR

2008

Annual Report: A Year in Exhibitions, 7th Gwangju Biennale, Biennale Hall, Gwangju, KR

2007

Open Studio after International Artist Fellowship Program, The National Art Studio, Changdong, KR

2006 Fast Break, PKM Beijing, Beijing, CN

Young Korean Artists 2006, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art Korea, Gwacheon, KR

<Awards>

2012 Young Artist Prize, Woojin Culture Foundation, KR

2009 Paradise Culture Foundation, Seoul, KR

2008 7th Gwangju Biennale memorial work Award, Gwangju Biennale, KR

2005 New Artist Trend, Seoul Foundation of Arts And Culture, KR

2002 5th Shinsegae Art Contest, Shinsegae Gallery, Gwangju, KR

2001 Winner, Alternative Space Pool Art Contest, Seoul, KR

<Collections>

Gwangju Biennale, Gwangju, KR

Gyeonggi Museum of Modern Art, Ansan-si, KR

Melton Prior Institut, Duesseldorf, DE

Ssamzie space, Seoul, KR

Jeonbuk Museum of Art, Jeonbuk, KR

Kunstpalais, Erlangen, DE

Heidelberger Kunstverein, Heidelberg, DE

Artist Pension Trust, New York, US

HIGURE17-15cas, Tokyo, JP

Critic

Haejun Jo: A Surprising “Exhibition” from an Amazing “Author”

Kim Sung Won

(Curator & Professor, Seoul National University of Science and Technology)

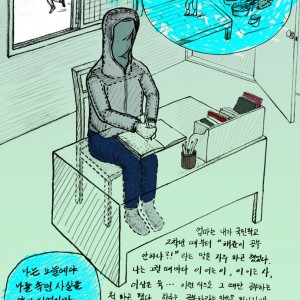

At first glance, Haejun Jo’s artworks appear to be direct, representational, and traditional, in terms of their form and their mode of delivering his themes and motifs. His drawings are often simple illustrations with accompanying texts, and his objets can seem to be a bit crude. But Jo’s art cannot be reduced to these drawings and objets, nor even to the personal and family histories that underlie his works. If so, he would not be receiving such interest and attention within the contemporary art field. Then what makes his works so interesting and worthy of our attention? When considering his art, the first thing that generally strikes one interest is the nature of his collaboration with his father, particularly the nature of these “oral drawings,” which are based on his father’s own memories. There are not many father-son collaborations in the art field, but the value of Jo’s work is not based merely on this quirk. The concept of translating one’s oral history into drawings is also rather unique, although somewhat reminiscent of traditional fairy tales, which appropriate the cartoon format. Jo’s collaboration with his father and his idea to base his drawings on oral narration have generated publicity and critical acclaim within the art world, but it now seems appropriate to move beyond these surface features to conduct a more in-depth examination of Jo’s status in the overall field of contemporary art, particularly the artistic context of Jo’s work and its relevance in relation with his fellow artists. This article addresses such issues, providing a mode for interpreting and appreciating Jo’s work in terms of its significance and contribution to the development of contemporary art. By analyzing certain issues implicit to Jo’s art (e.g. his collaboration, his storytelling, his role as an artist, the power of the art institution, and the complexities of artistic credit and the artist’s signature), we can grasp his overall intention, while simultaneously evaluating his place within the contemporary art field.

Over the past few decades, the art world has witnessed a silent revolt over the identity of the artist, and Jo’s work exemplifies many of the key issues at the heart of this controversy. It is well known that the artist Haejun Jo regularly collaborates with his father, Donghwan Jo. For more than ten years now, they have been promoted as a pair, with publications and exhibitions crediting their work as collaboration. Interestingly, the artist nominated for the 2013 Korea Artist Prize by the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art is Haejun Jo, but he has chosen to present an exhibition consisting entirely of works created by his father, Donghwan Jo. Thus, viewers who come to the exhibition to see the art of Haejun Jo will actually see and discuss works by Donghwan Jo. This is likely to cause some viewers to feel genuine discomfort and even embarrassment, as it should. Indeed, Haejun Jo’s works function as a trap, ensnaring the viewers and forcing them to ponder the identity of an artist. Is an artist the person who physically produces artworks, or the person who conceives, plans, and organizes the creation of those artworks? Who is the author of Haejun Jo’s works? Is it his father, who actually made the works with his hands, or is it Haejun Jo himself, who selected them for the exhibition? In contemporary art, it is not uncommon for artists to exhibit works that were actually produced by another person. For example, for his series Dear Painter, Paint for Me, the German artist Martin Kippenberger hired a Berlin sign painter named Mr. Werner to paint for him. By commissioning a sign painter to make works that he then exhibited in a museum, Kippenberger critiqued the idea that artworks could be reduced to the style of the artist, a concept that was popularized through the Neo-Expressionist artists of the late 70s and early 80s. By commissioning Mr. Werner to produce paintings, Kippenberger found the perfect way to add his signature to works without creating his own style.

Likewise, Haejun Jo does not strive to create his own style as an artist; in fact, he seems completely uninterested in expressing a unique style with his own two hands. After all, his exhibition consists entirely of works executed by his father. Nonetheless, they eventually become Haejun Jo’s works, and they acquire artistic value through Haejun Jo’s signature. The signature of the artist can completely change and redefine a work within the flow of contemporary art, such that it can actually influence the perception of the work’s formal features. As we know, the evaluation and appreciation of artwork was utterly transformed by Marcel Duchamp. By signing, exhibiting, and exchanging works created by Mr. Werner, Kippenberger was following in Duchamp’s tradition, and Haejun Jo’s works should be interpreted and appreciated in the same context. The drawings made by Donghwan Jo become the artwork of Haejun Jo, thus allowing them to acquire artistic value.

Another compelling aspect of Haejun Jo’s works is the way they simultaneously exploit and undermine the power of artistic institutions. In contemporary art, institutions have become so powerful that many artists have actively tried to resist, reject, or surpass them. Marcel Duchamp’s readymades exemplify the power of the artist’s signature to take priority over art institutions, but Daniel Buren has demonstrated that the artist’s signature is often unnecessary, because the institution itself is the signature. In any case, few can debate that, in contemporary art, institutions determine the artistic status and worth of an object, with or without the signature. At the very least, institutions have as much power as an artist’s signature when it comes to legitimizing an artwork. In this context, the work of Tino Sehgal is important, particularly his way of utilizing institutions. Sehgal’s art may be generally labeled performance art, in that he hires people to carry out his special instructions. Crucially, Sehgal only implements his works in art institutions, e.g. museums or biennales. Based on Sehgal’s instructions, the performers move and speak, becoming like “moving sculptures” inside the art institution. The setting is key, because it is only through the power of the institution that his work, which does not produce any material object, is traded in the art market. As such, the art institution functions as the absolute venue for contemporary artists, wherein the value and significance of their works are approved. Haejun Jo also cogently applies the power of art institutions, by primarily presenting large-scale exhibitions at prominent locations, both domestic and international. As such, he strategically uses the institution to transform the “oral drawings” of Donghwan Jo (non-artist, by the institution’s standard) into the artworks of Haejun Jo. Without the power of the institution, as applied by Haejun Jo, would anyone be interested in the objets and drawings of Donghwan Jo, an art teacher and unknown artist? But thanks to the sanctioning power of his son’s signature, the works are now eagerly embraced by the art institutions and establishments.

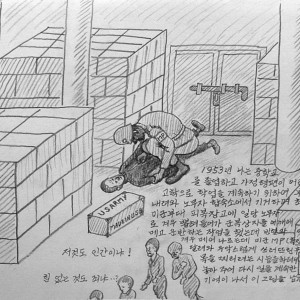

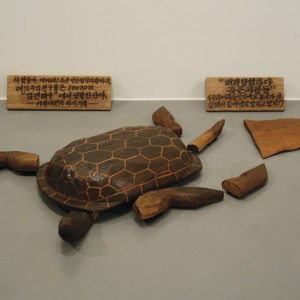

By strategically playing with the identity of the artist and using the power of art institutions, Haejun Jo is exploring the social relationship of contemporary art. Artists interfere in order to elicit real forms from existing theories and categories. One of the trends within the contemporary art of the 1990s was to recreate various social and professional models, including their methods of production. Extending this tendency, Haejun Jo takes on a variety of roles with his art projects, sometimes transforming himself into a curator, producer, or editor. Over the last decade, Haejun Jo has encouraged Donghwan Jo to produce drawings based on oral history, and then supervised the exhibition and publication of those drawings. For the 2013 Korea Artist Prize exhibition, Haejun Jo serves as a curator organizing a retrospective of Donghwan Jo. But what exactly does Haejun Jo aim to achieve by choosing to act as curator, rather than artist? What meaning does he hope to convey through his father’s works? Clearly, he wishes to express his father’s stories and memories, rather than his own. By curating and contextualizing the works of his father, Haejun Jo constructs a communicative link between father and son, while documenting the time period that he and his father lived. In this manner, he is no different from a curator who discovers an exciting new artist and connects that artist with an audience. This innovative use of a professional role, which is reminiscent of 1990s contemporary art, represents a strategy for creating works that interferes with the traditional artistic production of forms. Through this game, the final meaning and impact of an artwork is separated from the method of production, so that more emphasis is placed on how the artist exists in a work. Thus, in order to discuss the art of Haejun Jo’s works, we must focus on his curation and exhibition. Indeed, the way that the audience receives the private memories contained within the father’s drawings and objets depends entirely on how the son chooses to present them. This particular exhibition features a wide variety of works by Donghwan Jo: a sculpture entitled Let’s be Thinkers, which served as the starting point of the father-son collaboration; The Work that Failed to Win at National Art Exhibition, which the young Donghwan Jo submitted to the National Art Exhibition of Korea but got rejected; A Memorial Tree, an installation hung with various objets that Donghwan Jo carved and made throughout his life, based on his memories; and of course, the drawing series based on the oral history of the father, the family, and others, presenting their memories like the words of a narrator. All of these works evoke compelling questions about different relationships: the private relationship between father and son, the generational relationship between the father’s and son’s generations, the relationship between institutional art and amateur art, and the relationship between artist and curator. They can also convey the irony that is inherent to reality, as when the father’s rejected entry to the National Art Exhibition of Korea of the 1960s returns as a featured work in the son’s exhibition for 2013 Korea Artist Prize.

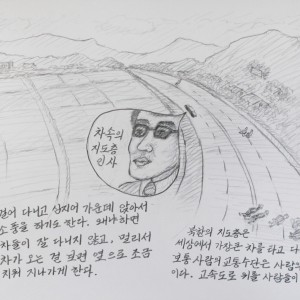

The most prominent strategy at work in Haejun Jo’s art is his method of relating private and historical memories. First, his father orally narrated memories of his everyday life for his son, and then those recollections were written down into colloquial words, and finally transformed into simple images to describe the scene. These drawings, based on “facts,” are delivered through various apparatuses that go beyond our expectations and common sense. Sometimes Haejun Jo uses the format of a picture book to build a relationship with his father’s private memories, his family history, and history itself. In another case, the audience must flip through dozens of picture frames, as if they were scanning the pages of a comic book. Elsewhere, he installed drawings inside a device that is like combination between a newsstand and bulletin board. It seems appropriate to use apparatuses like a comic book, newsstand, or bulletin board in a public space, since they act as a kind of meeting place, where the private and public memories converge. Through these works, the private lives and history of the Jo family encounter collective memories in a public place, thereby transcending the level of the individual and being absorbed into history. In addition to comic books, which are a minor genre of art that nonetheless remain quite familiar to us, Haejun Jo’s storytelling method also borrows heavily from oral tradition. By combining these techniques, Haejun Jo effectively rescues a person’s memories of everyday occurrences, which would normally be considered too trivial for inclusion in our “official” history. Thus, memories that would have simply vanished take on a new life by entering the public sphere and communicating with the masses. Visual art and story have evolved respectively in their own special fields. In particular, the contemporary art that we are typically given to “read” consists primarily of conceptual and abstract art. By presenting paintings that insist on being read, Haejun Jo boldly reinstates “storytelling,” which has long been alienated from the world of visual art. This act of recovery connects tradition and the contemporary, links the past and present, and merges story and concept.

Of course, there are infinite ways to discuss Haejun Jo’s works. We might take up the perspective of how they serve as “inbetween landscapes,” capturing ambiguous realms that exist in the midst of Korean contemporary history. In delivering the pain and poverty that are embedded in the memories of his father, Jo explores the landscape between imported Western culture and the distorted ideals of Korean society, as well as the huge gap dividing the memories of the previous and current generations. Another valid point of discussion is the tension, conflict, struggle, and reconciliation between father and son, or among individuals. However, I am particularly interested in emphasizing how Haejun Jo allowed his father to emerge as an artist by having him produce unique “oral drawings” of his memories and organizing the exhibition based on these works. This project is particularly relevant within the trajectory of contemporary art, as far as understanding how artistic value is established in today’s world. In other words, I wanted to talk about the forms in Haejun Jo’s works. Every artist produces forms, no matter what their method. Even if we cannot immediately recognize those forms with our eyes, no artwork can exist without them. In today’s contemporary art, new forms are being produced through manipulation of the artist’s identity, the act of collaboration, the status of the art institution, and the value of credit and the artist’s signature. Haejun Jo adroitly manages all of these elements as he successfully reconstructs, reproduces, and recreates everyday lives and memories into works of art. 2013 Korea Artist Prize represents the culmination of a decade of collaboration between father and son, which is unprecedented in the art world. Through this exhibition, the daily lives and memories of Donghwan Jo and Haejun Jo acquire a more official existence by being institutionalized as artworks. By mingling and interacting with the memories and experiences of thousands of new people, the private history of the Jo family escapes oblivion and stretches on into eternity.