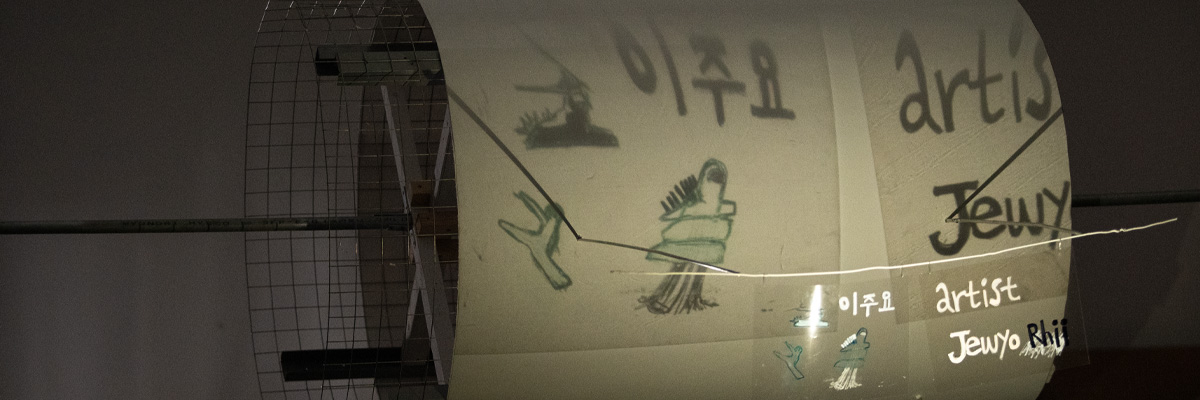

Jewyo Rhii

Jewyo Rhii (1971- ) has forged the psychological and physical compounds of variable, ephemeral, and mundane materials. As exemplified by her major works such as Night Studio, Two, and Commonly Newcomer, Rhii is interested in the implications of different combinations exploring the intersections of the private and public boundaries. Both in Korea and abroad, the artist’s activities are not confined to exhibitions but extend to a range of areas including performance and publication as well.

Interview

CV

<Selected Solo Exhibitions>

2017

THE DAY3, WALLS AND BARBED, Wilkinson Gallery, London

2015

OF PICTURES, Sophie’s Tree, New York

DEAR MY LOVE, ANTI-CAPITALIST, Galerie Ursula Walbröl, Düsseldorf

2014

COMMONLY NEWCOMER, Queens Museum, New York

JEWYO RHII, Wilkinson Gallery, London

2013

NIGHT STUDIO, Artsonje Center, Seoul [catalogue]

WALLS TO TALK TO, Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt

WALLS TO TALK TO, Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven [itinerary: MMK Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt] [catalogue]

2012

WALL TO TALK TO, Galerie Ursula Walbröl, Düsseldorf

2010

NIGHT STUDIO, Open Studio, Itaewon, Seoul [catalogue]

<Selected Group Exhibitions>

2017

DAWN BREAKS[Two Person Exhibition], The Showroom, KCCUK, London

DAWN BREAKS SEOUL[Two Person Exhibition], Artsonje Center, Seoul

2016

THE EIGHTH CLIMATE(WHAT DOES ART DO?, The 11th Gwangju Biennale, Gwangju

2015

UNKNOWN PACKAGES (DAWN BREAKS), Queens Museum, New York

LE SOUFFLEUR: SCHURMANN MEETS LUDWIG, Ludwig Forum Aachen, Aachen [catalogue]

2014

BOOM SHE BOOM: WORKS FROM THE MMK COLLECTION, MMK Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt

2013

SOME END OF THINGS, Kunstmuseum, Basel

2012

INTENSE PROXIMITY, La Triennale Paris, Palais de Tokyo, Paris

2010

THE RIVER PROJET, Campbelltown Art Center, Australien [catalogue]

MEDIA CITY SEOUL: TRUST, Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul [catalogue]

2009

EVRYDAY MIRACLE(EXTENDED) Walter and McBean Galleries, San Francisc

EVERYDAY MIRACLE(EXTENDED )II, REDCAT, LA, USA

<Selected Awards>

2010

Yanghyun Prize, Yanghyun Foundation, Seoul

<Performances>

2017

TEN YEARS, PLEASE [Co-directing], Namsan Arts Center, Seoul Foundation for Arts and Culture, Seoul

2016

TEN YEARS, PLEASE [Sole directing], Seoul Art Space Mullae, Seoul Foundation for Arts and Culture, Seoul

<Residencies>

2015

Artist-in-residency, Queens Museum, New York

2005

Artist-in-residency, The Rijksacademie, Amsterdam

<Collections>

Art Sonje, Seoul

Doosan Art Center, Seoul

MMK Museum für Moderne Kunst,

Frankfurt Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven

Kunstmuseum Magdeburg, Magdeburg

Henk Visch Foundation, Nederland, Eindhoven

Wilhelm Schürmann Collection, Germany

Critic 1

Crying Out Loud Amidst a World Overflowing with the Spirits of Uncertainty: “Love Your Depot!”

Somi Sim (Independent Curator)

For some time now, the world seems to be following the paths of variability rather than fixedness, flexibility than solidity, and migration than settlement. The world is inundated with all kinds of temporary and momentary objects, and this aspect is quite clearly witnessed within the art community. The matter of “Move or Die,” the catchphrase of logistics companies in the time of widespread global distribution, is visibly detected in the production mechanism of art.1 In our time when art is subject to death unless it moves like commodities, what are the aesthetic conditions of art? And what is the direction in which art practice should be oriented? Should an artist choose to continue to produce with agile mobility in order for the work to be circulated? Should s/he produce works that correspond to economic values? Or, should s/he continue to work hoping for global circulation that is to be thought of as an ideal art-making environment, namely the global supply chain? Jewyo Rhii, whose practice has been on a nomadic course, is one of the few Korean artists who has been on the chain mentioned above, the orbit of global circulation.

In the second half of the 1990s when Korean art directed its eyes to spectacular materiality and sociopolitical conditions for the sake of its leap into the international art scene, Rhii has already concentrated more on the marginal than the central, everyday life than art, weakness than rigidity, and situations and private relationships than forms, while keeping her distance from those tendencies. The artist has accommodated the discrepancies between institutions and individuals and embraced the psychology of those individuals who are inevitably alienated from the environment to confront the unstable present and the postponed future. As the work of Rhii is summoned here once again at this moment in time when uncertain spirits dominate the world, there is more to it than one individual’s narrative. Her world is linked to the examination of the entire ecology of art in which are included the institution of art and the conditions of art production. For her work so far has exposed those situations inconvenient and uncomfortable to her in the forms of objects and structures while seriously responding and reacting to the given familiar norms of art and society.

Her works, which are based chiefly on her daily life and surroundings, often disappear after the exhibition. This does mean that they are destroyed, extinguished, or vanished immediately after the show. Her works of temporary structures have traveled to various cities around the world together with the artist or have been left in the care of various people to linger about unfamiliar places and in other people’s lives. Her works are not very elaborately made to the extent that it could be disassembled right away in crisis, and this has imbued them with mutability due to which they have led persistent lives. As though adapting to the constantly changing environments from one place to another, her objects have modified their bodies and changed their arrangements, learning their own survival tactics. Here, the temporary structure can be seen as a kind of microsystem that confronts this stubborn world and its fossilized institutions. In this way, the artist’s work has been postponing its destiny into the future via interminable mobility and temporariness.

For the past two decades or so, her artistic practice has taken place in the course of her transnational voyages to different countries including Korea, the U. S., England, Germany, and the Netherlands. The exhibitions in which she participated contain and present the trajectory between the exhibitions in various cities that she attended one after another and her journey between one place to another. Her solo show, Jewyo Rhii (2006) held at SAMUSO in Seoul showed the whole process in which the works made during her two-year stay in Amsterdam were transported in carts. Years later in 2013, her solo exhibition held at the Art Sonje Center, Night Studio, unfolded its journey from a studio in Itaewon in 2010 to its tours to the Netherlands and Germany and its return to Korea in 2013, showcasing the traces of its travel routes and changes. As Charles Esche, Director of Van Abbemuseum, which was one of the venues, points out, Rhii’s objects have retained the changes, transformations, and spatial and temporal passages that they have gone through in quiet voices while improvising to adapt to the inconvenient situation of moving from one place to another and from one city to another.2 The power of the indeterminate structure found in Rhii’s work does not merely lie in its adaptation and sustentation in reality. The word, “weak” does not mean “easy to break.” With every move, she has brought with her the vestiges of life that could not be sustained in the previous place, bringing with her its postponed destiny to the next place, keeping its time alive.

Thereafter, the activities of Rhii have been focused on forging close relationships with her colleagues and territorial expansion. Just as living one’s life requires more than just one’s own volition, the artist has been working in solidarity with others to augment minoritized voices, as well as gradually working towards establishing a shared stage for their coexistence. In Dawn Breaks (2015–2018), for which she collaborated with Jihyun Jung and which toured New York, Gwangju, Seoul, and London, the artists opened their works up as a stage for younger artists. For Ten Years, Please, a performance at the Namsan Arts Center in 2017, Rhii summoned up the stories of objects that had been left with so-called trustees after her solo show held ten years before. As living territories and stages for those things (beings) that cannot settle down in reality, her works have kept sustaining themselves through their interactions with the time of others. As Rhii sent her hello to those objects that she had said goodbye to ten years ago, I cry out to Rhii who may well be somewhere on the trajectory of her continual migration, “Come back!” This ardent cry for her is my mimicking of Rhii’s Lie on the Han River (2003–2006). A cry for an old lover knowing there is no chance to meet him again. But then what is the use of calling Rhii again to this place, which is flooded with all kinds of temporary, momentary, and volatile things? Am I trying to officially designate Rhii as a visionary who foreknew the coming of the global circulation system already in the 1990s or as an artist who translated an aspect of the world of uncertainty early on? Or is it my desire to weave the sparkling story that is left behind in between her leaving and returning or the residues of her global narratives into a trajectory of contemporary Korean art?

This vague wish of mine was nothing but a naive dream that I had without understanding the reality for the artist. In 2019, Rhii has returned. But she was not alone. She has come with the objects whose lifespans have been stretched with every one of her departures. As if parading the time that they have endured and the traces of their move, the objects are put in crates for international shipping, emanating a kind of grimness. The four creates departed somewhere in Düsseldorf, London, New York, and Seoul and have been transported precisely, almost to the point of cruelty, to its destination, a gallery in the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, via different logistics companies. These loads of objects are works of art that contain the entire life of an artist and simultaneously what became superfluous due to its inability to be distributed within a commodity-based economic system. Stuck in the darkness of boxes and storage, they are also things that are subject to the desperate destiny of waiting for their postponed lives to be discovered someday. In the dark of these creates are hidden the true reality of works of art veiled by the splendors of exhibitions. Before her huge loads of works resulted from Rhii’s continuous production, the question of where a work of art’s present life stands cannot but be asked. An artwork that has been trapped in the dark for years waiting for the box to be opened. It is the most real, isn’t it? In our times, to be able to subsist in storage is fortunate enough when the work is not supplied anymore. Countless works by artists, for which even this condition is unavailable, have been innumerably destroyed.

To summon Rhii at this present moment is to track down the ambivalent relationships among the survival model for contemporary artists, the institution of art, and the global system. The core agent by which today’s contemporary art community is formed and operates is its supply-chain network. In the circulation system of commodity and capital, the model of supply and demand functions through the pursuit and accumulation of profit. In the art world where there are gaps between supply and demand, however, the supply-chain network tends to be more busily active to meet the demand. The recent expansion and diversification of the institution of art’s role are brought about by the need to maintain this supply-chain network. Accordingly, contemporary artists (in other words, makers, creators, or agents) fall into the situation in which they cannot cease to make new products in order to survive the supply-centered circulation system. The reality is that the element of solid materiality is disregarded for more rapid production and agile circulation. An artist can continue doing his/her work, pretending to be unaware of this condition. Yet Rhii puts aside her own work and lets herself become a level-headed platform designer to battle against the conditions and limits of art production, in order to secure not only her survival but also that of her artist colleagues, and the young sculptors who are forced to destroy their works.

Love Your Depot by Rhii, where artistic imagination, which has been regarded as relevant solely to creative endeavors, is applied to an alternative economic system is a platform for the conceptualization and experimentation of contents as well as a sustainable system and infrastructure for works of art. For four months, the museum is freed from the given function of art viewing and is transformed into an “alternative platform” and a “living storage” for the artworks that are discarded and neglected by reality. This storage is not an unattended dark space that can do nothing but wait for supply and demand. Having broken through the darkness and revealing itself as it is to meet people, it is a storage that is alive as it communicates through its secondary activities related to its primary function and other contents. The artist’s plan to continue to work on this project not just in this show but for the next three years is the most practical and courageous response to the cry of “Come back!” attesting to her intent not to react to it temporarily or in a roundabout way. Despite the contradictions and limits of the institution and ecology of art, Rhii reexamines the ethics and conditions of creativity that an artist should uphold and mounts a challenge together for the invention of an alternative platform through which the destiny of temporary postponement can be defied. It is espoused that this “living storage” be a new territory where the anxiety that seizes us is overcome so that our uncertain present is stabilized and the time of our future is ensured.

1. Debora Cowen, The Deadly Life of Logistics, trans. Kwon Beomcheol, (Seoul: Galmuri, 2017).

2. Charles Esche, “What remains… ambivalent relationships (with people and things),” Jewyo Rhii: Night Studio, Sunjung Kim et al. (Seoul: SAMUSO, Workroom Press, 2013), 101–103.

Critic 2

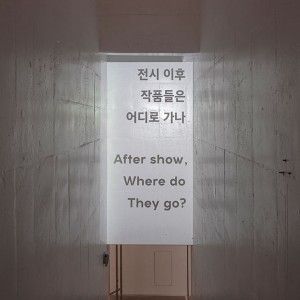

After the Show, Where Do They Go?

Charles Esche (Director, Van Abbemuseum)

Artworks are not people. They are not alive in any conventional sense of the word. Yet, they are not inert either. Through the work of the artist, the original base materials are transformed into something with meaning and coherence. The transformation is almost alchemical. It confers a meaning and value onto objects and materials that might otherwise go unnoticed. Once an artwork is shown in public and recognised as such by others, it becomes part of a collective cultural archive and it acquires a new status, one that needs the care and tenderness that, in the best cases society would also wish to provide for its constituents.

In this way, a particular artwork acquires its special identity as “art,” something that is bestowed on it not only by the individual artist but also by everyone with whom it has come into contact. In this process, the work, modestly but inevitably, takes its place in the history of human expression. With that change, comes a new responsibility for its fate, one that rests no longer only on the artist’s shoulders but is gradually transferred to and shared with society at large. Artworks become heritage in this way, and heritage becomes a way to build shared loyalties and a common sense of who is what and where they belong. Ultimately almost all human cultural communities learn to identify themselves in part through the artworks that its culture has produced at one point or another in its history. Particular works of art becomes defining of a community and a shared origin and destination. Every artwork has the potential of going on this long trek towards becoming part of a culture’s heritage, but it is usually most precarious at its beginning, and it is at the beginning that the artist Jewyo Rhii’s work starts.

Rhii’s project Love Your Depot is a proposal or prototype for an artistic and social service, and a way to care for artworks that might otherwise be abandoned. As an artist, Jewyo Rhii is thoroughly aware of the physical and emotional labour that it takes to make an artwork. As a teacher, she has learnt to put her trust in art’s power to express and transform human emotions. Yet, she has seen the struggle of her fellow artists against the demands of the market economy and urban development that squeeze out differences and irregularities in their search for the financially efficient use of human and other resources. Not only is this obsession with efficiency existentially hard on the artist as a human being, it is also unlikely to align with the interests of community and identity building that are the actual hallmarks of a good artwork. Instead, the inadequacy of the artist in the market, and the inadequacy of the market for the good of art together create a perfect storm of erasure, contradiction and struggle between values. The irony here is that these values do not necessarily need to compete or even relate to each other but could learn to co-exist. Love Your Depot is a singular and, as far as I am aware, unique response to this problem of co-existence that is both very practical and unavoidably political in its demand for a parallel system of value and care.

The one institution where many people might expect the conflict to be resolved is the art museum, to which the collective responsibility for keeping recent heritage is often delegated. In these terms, museums should be exceptions to the rule of the free market, though increasingly and sadly they are not. Many museums are private initiatives whose income derives and is dependent on the success or failure of a private company. Even those that are funded by less precarious city or state taxes have often been overwhelmed structurally by the primacy of the market in the past 30 years and adopt its language and sense of worth, following the tastes of the art market or purchasing the artworks that are designed to attract a large, affluent public. To flourish fully, art needs something more than its monocultural institutional landscape. It needs places that offer alternative or parallel value systems, the kinds of systems that museums do sometimes still try to offer and that Love Your Depot is demanding.

This is one reason why it seems very important that the first prototype installation of the project can be found inside a museum. Here, in a space that must still have the potential to be different from the commercial imperative outside, Love Your Depot tries to make a home, though the fact it is not entirely comfortable with the rules and regulations of the museum indicate the gap between what most museums are in practice and what it might be in another situation. For museums, can still claim the power and the ability to inspire artists to make work, to care and to support for them and their productions and ultimately to contribute to a new communal identity for their public, one that grows out of a tangible and non-ideological experience of the 21st century. To do that, museums need time, resources, care and understanding — precisely the things Love Your Depot is seeking to provide. The ideal of an art museum is that it becomes a place where the creative expressions of people in and around its environment are retained and embraced in order to inspire present and future generations. For anyone who wants to think beyond the economics of survival in the here and now, that has to be a valid and worthwhile activity, yet Rhii’s project shows what might need to change in the basis of the museum system in order to make that possible.

The different forms of how to care physically about artworks that are usually hidden from public view and sometimes simply abandoned in museums are made tangible here. Through putting different storage and shelving systems on show and sometimes pushing them to the maximum in terms of how high they can go or how much they can carry, Rhii’s installation makes clear the burden that she is displaying. In their ambition, the storage systems take on the appearance of sculptures themselves, breaking the divisions that would usually reign in the museum and calling into question the definition of art, as many artists have done before her. Yet, it is not just this formal aspect of their preservation that Love Your Depot considers. The team around Love Your Depot busy themselves with the question of meaning and interpretation, allowing the works to gain a voice through youtube videos and other forms of intimate and opinionated mediation. Such personalised forms of interpreting an artwork also push against the limits of the museum’s self-understanding as a place for more ‘neutral’ or institutional discourse. Finally, the making public of the apparently random juxtaposition of works next to one another in the open storage also begs for connections to be made and common narratives to emerge in the way that museum curators are also required to do, only this time the stories are generated on the spot and in the minds of whoever comes to see the work. As with the storage systems and the forms of interpretation, in this accidental process of exhibition, Rhii asks what are the limits of museum practice and what might need to change in order for art to fulfill its social potential.

While the museum and the archive are crucial to understanding Love Your Depot, it is the artist as a figure and as an emotional human body that is really at the centre of its attention. Artists, in this project, are seen as both fragile and endangered while also being significant and potentially powerful actors in society. Their fragility (or precarity) comes from their individual condition, one in which they are often left to fend for themselves or to try to look after their own works without the institutional structures that protect other producers of culture or workers in general. At the same time, its individual condition allows them to gain insights into life and humanity if they are provided with enough time and space. In this state, they are asked to destroy their transitional art works, things that they might have just recently spent all their psychic and emotional energy to make. Love Your Depot is partly then simply a plea for respect, time and consideration to be given to artists because it is in that way that they can make the most of their contribution to society. By constructing a structure that temporarily allows their works to continue to exist until they no longer need to survive, Rhii hopes to offer comfort where there is often none at all. Importantly, it is not a plea for eternal preservation. Love Your Depot sees itself as a time limited holding ground in which the artist who made the work can always choose to have it respectfully discarded, indeed such careful destruction is part of the service. Thus, Love Your Depot is simply a device to delay, to reflect and to consider when and if an artwork can become art in the communal sense of the word. It protects the time between something being made and something becoming what it hopes to be, in a way that could be understand much like a human childhood. To return to our starting point then and while it remains true that artworks are not people, Jewyo Rhii shows us that treating them in similar ways might be a start to rethinking the role of art in society and how each of us can give value to the things and the people around us in a more caring, respectful way.