Hyesoo Park

Hyesoo Park (1974- ) has questioned the universal values and unconscious thoughts that are affecting our society and groups within it and further gave form to the values of the individuals’ memories and lives through her solo shows including Nowhere Man, Now Here is Nowhere, Definition of Botong, and The Dream You Thrown Away. For the visual realization of these perceptions and intangible values, the artist observes our surroundings, gathers data by doing meticulous researches, and when in need collaborates with experts in related fields.

Interview

CV

<Selected Solo Exhibitions>

2016

Now Here is Nowhere, SongEun ArtSpace, Seoul

2013

Project Dialogue Vol. 3 ᅳ Definition of Botong (Archive), SongEun Art Space, Seoul

2011

Project Dialogue Vol. 1 ᅳ Dream Dust, Kumho Museum of Art, Seoul

What’s Missing, Posco Museum, Seoul

2009

Project Dialogue ᅳ Archive, SOMA Drawing Center, Seoul

2008

The Locked Room, Gallery Won, Seoul

<Selected Group Exhibitions>

2019

Viborg Animation Festival, NYT Viborg Museum, Viborg

The Phenomenon of the Mind: Facing Yourself, Museum of Contemporary Art Busan, Busan

2018

SCENE & UNSEEN, Castle d’Aspremont-Lynden, OUD-REKEM

Flip Book, Ilmin Museum, Seoul

re:Sense, Space*c, Seoul

Hard Boiled and Toxic, Gyeonggi Museum of Modern Art, Ansan

2017

Do It Seoul, Ilmin Museum, Seoul

Border 155, Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul

2016

Do Boomerangs always come back?, Kasteel d’Aspremont-Lynden, Oud-Rekem

Somewhere @ Nowhere, SOMA Museum, Seoul

Artifariti 2016, CICUS&ELBUTRÓN, Sevilla

2015

APMAP ᅳ Researcher’s Way, AMORE Pacific Mauseum of Art, Yongin

Winter Open Studio, Gasworks Studio, London

The Future is Now, Friche la Belle de Mai, Marseille

Open Studio, Jan Van Eyck Academie, Maastricht

Future Love Nature, ZZP Fabriek, Maastricht

2014

The Future is Now, Maxxi Museum, Rome

2013

LOVE Impossible, MoA Museum, Seoul

2012

Language But No Words, Space MOM museum of Art, Cheongju

2011

SeMA 2010 — Chasm in Image, Seoul Museum Of Art, Seoul

2010

Up and Comers, Total Museum, Seoul

<Selected Awards & Artist Selection>

2014

SongEun Arts Award Grand Prize, SongEun Art Foundation, Seoul

2010

Kumho Young Artist, Kumho Asiana Cultural Foundation, Seoul

<Selected Residencies>

2019

hite Block Residency, Cheonan

2015

Gasworks Residency, London

2014

Jan Van Eyck Academie, Maastricht

2010

MMCA Residency Goyang, Goyang

2009

Aomori Contemporary Art Center, Aomori 2008 SeMA Nanji Residency, Seoul

<Selected Collections>

Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, Gwacheon

Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul

Museum of Contemporary of Busan, Busan

Collection Hendrickx-Mannaerts, Schoten

Collection Van Laethem-Croux, Hasselt

Critic 1

Recommendation

Youn Ok Kim (Curator, Kumho Museum of Art)

RecommendationYoun Ok KimCurator, Kumho Museum of ArtHyesoo Park has communicated visually the collective conscious and unconscious underlying our society and the memories and values that individuals have lost in their lives and everyday living. To give visual forms to these memories and values, the artist collects clues for her works in many different ways: the scrupulous observation and constant recording of others or her surroundings; surveys; and the collection of various people’s articles through online advertisements. The resulting artistic outputs are presented in diverse forms such as drawing, video, installation, archive, publication, and performance.

Under the inspirational influence of the film, After Life (1988), since 2005, the artist collected the lost memories of individuals in the project, What’s Missing? (2008− ), after which Park started to make full use of surveys in the making of her works. Park has also harvested in a variety of ways the unconscious and values underlying our lives: Ask Your Scent (2008) is a project in which a perfumer makes a personal perfume for each visitor; in project Dialogue (2008– ), she collects dialogues of others in public places to which the answers, analyses, and advice of experts from various fields are added. Moreover, the results of her collecting are translated into diverse forms: publications; a new form of installation work accompanied by the participation of a fortune-teller and a psychiatrist in Project Dialogue Vol. 1 — Dream Dust (Kumho Museum of Art, 2011); and A Drift in the Dream (2011), an experimental theater with the participation of a dancer. Collaborating with professionals from other areas such as theatre, literature, dance, and psychiatry, Park reconstructs the confessions of numerous individuals and groups.

For the past decade, the artist has looked into subjects such as the “deserted dream” or a “demanded normality” and divulged together with us as both the co-makers of the exhibition and the audience the dreams and values that individuals have lost while conforming to the ideas and norms that families or social communities request or impose. Park’s works enable us to awaken to what we do not perceive and thus overlook, criticize the paranoiac and selective nature of our point of view and thinking, and sometimes console our minds fatigued by the propositions of the systems and groups of our society that we are obliged to obey.

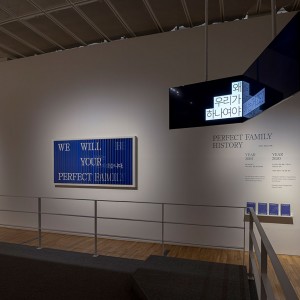

In the Korea Artist Prize 2019 exhibition, Park speaks of the collective “we” and the background of Project Dialogue Vol. 4 — Our Unknown Country. While her previous projects questioned the values that individuals abandoned in the desire to belong to the collective, or the “normal” or “ordinary” that the collective entity compelled them to comply with, this project attempts to define what kind of “we/us (group)” is valid to each individual and to diagnose where the “we” of Korean society are headed as the society is strongly inclined to various cronyisms including nepotism, school cronyism, and regional cronyism. It also starts with a survey on various publics’ thoughts on “we/us,” and the results of the survey and their statistical analysis are transfigured into an installation work and an archive shown at the gallery. Also, seminars and discussions by professionals from diverse fields such as psychiatrists, anthropologists, and economists are to be held to share with the viewers the process of discovering “the ‘we’ that we do not know.”

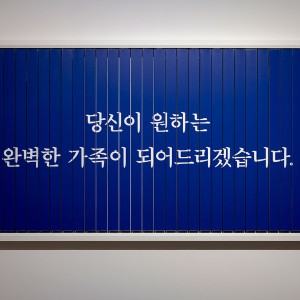

What makes Project Dialogue Vol. 4 — Our Unknown Country worthy of one’s continuous attention is, unlike previous works, the fact that it concretely implicates the directional orientation of this project’s output and the node between this and the following project. In this exhibition, the artist provides a glimpse of Perfect Family — which Park plans to continue to develop in the future—and includes narratives of the “family rental” business for one person-households, which is increasing rapidly. In Perfect Family, the artist proposes a new alternative “URI (we),” and viewers can look forward to a healthy community of “URI” of the near future suggested by the artist.

As examined so far, Park allows our thoughts to be redirected to the individual and the collective, life and dream, the intangible and the tangible, language and image, and a multitude of memories and values that are meaningful in our lives. The intangible languages expressed by the individuals and groups in her works tell stories about the artist herself, and at the same time those about all of “us.” The artist makes viewers actively engage in the process of her work on the one hand, and on the other involves herself in the lives of the viewers. As if they were plays where there is no beginning or ending and where all of us become performers since no boundary exists between the audience and the stage. For the past twenty years or so, the artist Hyesoo Park has been carrying out the most fundamental and most difficult definitions and functions that contemporary art is supposed to fulfill, not through superficial or pretentious gestures but through her own daily life and creative endeavors.

Critic 2

Hyesoo Park’s Project Dialogue Vol. 4 — Our Unknown Country: Changing “Antagonism to Agonism” and “Enemies to Adversaries”

Juhyun Cho (Chief Curator, Ilmin Museum of Art)

Hyesoo Park uses her works to strike up a conversation. Entering the exhibition space, visitors are asked, “Are you botong?” (i.e., “Are you normal?”) People might unwittingly respond to their neighbors, but there are more questions yet to come. Next, Park asks, “What dream did you have to sacrifice?” Now visitors sit at a keyboard and type the secret stories that they have been keeping bottled up inside them. Upon stepping into the exhibition and taking up this conversation with the artist, visitors can voluntarily fill out a survey, write an essay, draw a picture, chat with other people (even if they are strangers), or find another way to share the thoughts that they have been holding onto. For the past ten years that Park has been presenting Project Dialogue, she has also been collecting and analyzing data from visitors’ conversations, emotions, and motions. After being interpreted and treated by the artist, this data is then used to visualize the collective memories and unconsciousness of Korean society. In this exhibition, this data is again revised and transformed into an array of artistic creations, including archives, installations, poetry, theater, performance, and video. The result is an innovative new “conversation machine” that can enable ongoing interactions among people from different times and places.

Borrowing her methodology from social sciences, Hyesoo Park provokes people to engage with controversial topics and platforms through artistic practices, which are quite different from the work of psychoanalysts or politicians. In particular, Park’s Project Dialogue functions as critical art by altering social boundaries and transforming audience members into active agents of intervention. How is this possible? The mechanism of her works can be roughly divided into three concurrent processes: ① initiating a relational program based on fictitious hypotheses, ② creating an “agonistic” space through “dissensus” and ③ proposing a virtual business model. By striking up a conversation, Park’s artistic practices generate an endless stream of questions, awakening peoples’ dormant desire for self-transformation.

1. Relational Program Based on Fictitious Hypotheses

Exhibited at Korean Artist Prize 2019, Project Dialogue, Vol. 4 — Our Unknown Country is a theatrical stage for a psychodrama, a research lab for a social scientist or psychiatrist, or an embodiment of social dissensus and agonism. The work is an extension of previous projects in which Park visualized the life values or distinctions that ordinary people were forced to surrender in order to live from day-to-day or to belong to groups or communities. This project constructs an agonistic space in order to reveal the hidden, irrational, and collateral effects that are concealed within any group signified by the word “us.” To begin, Park conducted a preliminary survey among Koreans who consider themselves to be “middle-class,” thereby revealing the subjective terms by which they define the middle class. She then studied the boundaries, conditions, and characteristics of this group—i.e., “us”—and used the results of her research to experiment in various ways with the conflicts, dissensus, and politics related to the “other” who exists inside “us” but is still represented as “not us.”

Our Unknown Country is an inclusive platform comprising a survey, analysis, experiments, Forum Theater, documentary, archives, installations, and even a virtual corporation. To encourage the active intervention of the audience, the project takes a multitude of forms, including 1) the visual archives of the original survey and analyses, 2) a documentary video that translates the artist’s analyses of relevant issues into art, 3) display cabinets of objects collected during the making of the documentary, 4) a virtual business model as an alternative apparatus to reality, and 5) a theatrical psychodrama wherein the central agonism of all the narratives is choreographed and performed. By appropriating these social-science models, the artist devised a relational program that serves as a platform for interactions. Hence, the artist’s work is actually created via the audience’s direct intervention within the social sphere as one functional model.

How does Hyesoo Park’s relational program operate? First, the preliminary survey was distributed to 507 members of the Korean middle class, including government officials, office workers, housewives, etc. Then, in collaboration with psychiatrist Yoowha Bhan, Park analyzed the parameters of the group that these Koreans identify as “us.” In her analyses, Park focuses intensively on the extreme dichotomization of Korean society. Notably, the survey participants overwhelmingly chose “family” as the group that they most strongly identified as “us,” by a wide margin over affiliations of nationality or employment. This result is quite interesting, given that the dissolution of traditional families in Korea, as demonstrated by the rise of one-person households, has been a widely discussed phenomenon in recent times. Thus, the data seems to show that, since Korea’s rapid economic growth has leveled off, today’s middle-class Koreans no longer believe in a safety net provided by their country, society, or work place. The survey also suggests that today’s Korean youth do not nurture big dreams and are reluctant to take risks. At this point, the Korean middle class believes that family is the only group that they can count on for warmth and security as they face an uncertain future.

At the entrance of the exhibition, the survey report is displayed for viewing in the same area where new visitors jostle around to fill out the survey, creating a very unique atmosphere. Notably, Park did not originally intend to review the objective social data acquired through the survey. Then at what point does Park’s survey (in collaboration with a psychiatrist) diverge from the usual practices of social scientists to become a work of art? By using the results to propose a highly probably yet fictitious hypothesis (within the 0.05% margin of error), she leads viewers into a space of contemplation that eventually leads to agonism. In Who Are We, Park enacts a bit of psychological warfare by transforming the survey results into a fantastical hypothesis about the contemporary Korean family, suggesting that the strict Confucian familism of the past may be a solution to the uncertain future. Hence, Park has produced a relational program that functions by exposing the hidden conflict, irrationality, and side effects within the ideology of family.

Park also explores the underlying issues of familism in the documentary video To Future Generations. By examining the death of a family, the video incisively reveals how the conception of family based on bloodlines that is still prevalent in Korea has been co-opted by neo-liberalism. Documenting the work of four estate administrators (who oversee the distribution or disposal of people’s belongings after they die) and four funeral directors, the video shows various places related to the deceased (e.g., homes, funerals, mortuaries, crematoriums) that are devoid of family or friends. In particular, the video reveals the stories of elderly people who lived and died alone, sometimes remaining undiscovered for days or weeks. Sadly, many people facing such a lonely death are further burdened by governmental and social discrimination. Hence, the video illuminates the specious and harmful notions related to the ideology of familism. What is the exact nature of the affinity that people feel for their family? By raising such questions, Park forces us to consider whether the popular fantasy of “home sweet home” is merely a fallacy that society has indoctrinated in us. And if this is the case, she further wonders whether a new system prioritizing individual rights over the family should be implemented.

The video includes narration of the poem To Future Generations by the German playwright and poet Bertolt Brecht, written in 1934 while he was in Denmark taking refuge from the Nazis. This poem can be interpreted as the last will and testament of people who dedicated their lives to their country, only to die alone. In one corner of the exhibition, Park displays the belongings of a man whose death (and body) were not discovered for some time, even though he was a patriot and upstanding citizen who had fought in the Korean War before becoming a high school teacher. Visiting the man’s home, Park found medals, awards, and other memorabilia from his military service, along with his diaries and notes detailing his loneliness. As the man wrote, his children refused to accept his keepsakes, which is how they ended up in the exhibition. What does it mean when a man of such national merit dies alone, severed from his country, community, and family? Perusing the exhibition, viewers cannot help but ask such questions over and over.

2. Creating an Agonistic Space through Dissensus

The centerpiece of Our Unknown Country is a special theatrical presentation entitled No Middle Ground, staged inside a large space that was designed after Geumsan Church in Gimje, one of Korea’s first Christian churches. Park thus invokes one of the most polarizing issues in Korean society: religion. The earliest churches in Korea, built in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, were constructed in the shape of an “L,” in order to create separate seating for men and women, in accordance with the existing Confucian tradition. The design of this church represents the Korean society of today, after more than a century, when gender equality has also spawned a culture of hatred and misogyny. Of course, Korea is not alone in dealing with a culture of extremist contempt. Since the fall of the Berlin Wall, the unfettered spread of capitalism has given rise to a standardized world order that demands conformity, which has thus triggered a backlash of extremism. The world is becoming increasingly polarized by nationalist thinking that is fueled by hatred, a lack of communication, and political retrogression.

As Belgian political theorist Chantal Mouffe has diagnosed, we are now living in the era of post-politics. Thus, Mouffe contends that critical art must seek to create agonistic spaces in order to confront global issues (e.g., economic inequality, terrorism, cultural imperialism) brought on by the consensus entailed by capitalism. The stage of Hyesoo Park represents just such a space. As the title suggests, there is no intermediary space in No Middle Ground, which is sharply divided between into two groups: “US” and “NOT US.” Visitors must exercise their own agency by reorganizing the boundaries based on perceived or potential conflict. Meanwhile, Forum Theater: URI is a lecture performance and a type of psychodrama designed in collaboration with experts in psychology, sociology, economics, and cultural anthropology, and based on five themes that Park selected from the results of the survey report Who Are We. Unlike the unidirectional communication of most lectures and seminars, however, the Forum Theater generates agonism by subtly coaxing the audience to participate by placing them in conflict situations. As they are induced to create boundaries for excluding or alienating other people, the discussion participants directly experience the dissensus between individuals and groups that has come to characterize many Korean communities.

For example, the Forum Theater that was held on October 31, 2019 was called “The Discontented.” Designed by psychiatrist Yumi Sung, the discussion was actually a psychological experiment about social division. Acting as an authority figure, the discussion organizer (i.e., Yumi Sung) arbitrarily divided the forty participants into two groups (i.e., “US” and “NOT US”), and then presented one group with flowers and the other group with foxtail plants. After receiving these “rewards,” each group was guided away from the other group and then asked to speculate about the organizer’s criteria for dividing them. The organizer then reappeared and stated that the “US” group consisted of people that she liked, while the “NOT US” group included people that she hated; yet the organizer still did not reveal any criteria for her affinity or hatred. Next, the organizer announced that only people from the “US” group who remained until the end of the discussion would receive a reward, and then offered participants a few chances to move from one group to the other, either by their own choice or someone else’s. Through this process, the participants experienced heightened forms of the psychological perceptions of competition, reward, alienation, conflict, and discontent that everyone encounters within a community. Indeed, the primary purpose of the experiment was to bring these perceptions out into the open.

As the organizer, the psychiatrist set up the hypothesis that the participants would not like being kept in the dark about why they were being divided, being “liked” or “disliked,” or being given different tokens (i.e., flower vs. foxtail). Participants were then asked to make sacrifices for the group based on their own reasoning; thus, if they wished to bring someone into their own group, a current member had to be let go. But even though this experiment was designed by a psychiatrist in accordance with psychoanalytic methodology, it developed in unpredictable ways that entered the realm of art. Of course, unlike the members of “real” communities, the participants of this Forum Theater had no affiliations or intimacy with one another, and they were fully aware that they were attending an art function. Hence, the issue of changing groups was not a matter of life or death, as it might be in real life. Perhaps that is why most of the participants simply looked bemused, as if waiting for some stronger stimulus.

Deviating from the organizer’s intentions, this type of attitude actually reflects an interesting characteristic of young Korean adults, who themselves represent a type of alternative community. Rather than simply acquiescing when the organizer attempted to exercise her authority, the young participants instead voluntarily surrendered their reward, thereby amplifying the pride and team spirit associated with the “NOT US” group. In this way, they were able to confer authority to someone representing the supposedly marginalized group (in this experiment, it was the artist Hyesoo Park), which enhanced their own feelings of solidarity and entitlement. In this way, the work fulfilled Mouffe’s appeal for critical art that raises questions and awakens people’s desire for self-transformation: “According to the agonistic approach, critical art is art that foments dissensus that makes visible what the dominant consensus tends to obscure and obliterate. It is constituted by a manifold of artistic practices aiming at giving a voice to all those who are silenced within the framework of the existing hegemony.”

As an alternative to our era of consensus, Mouffe proposes the concept of agonism, which revolves around acknowledging the rights of one’s opponent or antipode in the “us and them” relationship. Rather than issuing reproaches for certain incidents, critical art seeks not only to create an agonist environment wherein the two sides must engage with one another, but also to liberate the oppressed through dissensus. This corresponds to Jacques Rancière’s argument that critical art should intervene in the “distribution of the Sensible” by “making the invisible visible and the unheard heard.” The unpredictable results of this experiment go beyond the distribution of the Sensible that determines the boundaries by which we define our place in a community. With the Forum Theater, Hyesoo Park produces a space where participants experience conflicts and confusion within their agreed boundaries, so that the resulting dissensus shatters the agreement.

Rather than trying to directly change the existing system or discourse, Park instead aims to activate people’s thoughts and feelings, ultimately making them into the agents of their own dissensus. Through this methodology, the “discontented” who participated in the Forum Theater became joyous transgressors who broke with convention and created new boundaries. Through her artistic practices, Hyesoo Park helps people modify their own senses and perceptions, thus enabling them to see, hear, think, and speak the sensations that they became aware of while experiencing discontent and dissensus with the structure of the distribution of the Sensible.

3. Proposing a Virtual Business Model

You are not alone.

With trust and honesty

sincerity and responsibility

We will be there as your family

for your significant day.

from Perfect Family Inc.

by Hyesoo Park

In Hyesoo Park’s exhibition, she uses her own hypotheses and interpretations to coax visitors to become autonomous producers of critical art in a laboratory space. But at the same time, she also operates another type of relational program in the form of a virtual business model. To do so, she first researched various role-playing services in Korea, as well as the service of “renting a family” that exists in Japan. Based on such services, Park created Perfect Family Inc., a virtual company specializing in human rentals or stand-ins. The work consists of a catalogue, website, and advertisement for the company. On the inside cover of the catalogue, the company logo is royal blue and resembles a traditional coat of arms, thus conjuring thoughts of European royalty or aristocracy. The logo is accompanied by the company’s motto: “The leader in the human rental business/ The happiest family you could ever dream of/ Perfect Family.” Like a commercial for an insurance company, assuring us of protection from an insecure future, Perfect Family Inc. claims to partner with a strong capitalist network of companies offering diverse services, such as professional actors, event planning, funerary services, elder care, psychiatric care, and match-making. Perfect Family Inc. thus appears to be a dependable family who will comfort and protect us from the hardships of sickness, old age, and death, which we were once assumed to be provisions of nature.

In addition to handling big events such as weddings and funerals, the company also deals with everyday activities that require consideration of ethics, etiquette, and traditional conventions, such as texting your parents to fulfill your filial duty, meeting with your child’s teacher, making apologies, breaking up with your partner, or quitting your job. Emblazoned on a billboard, the image of the ideal nuclear family — mother, father, son, and daughter — accompanied by the company’s slogan “YOUR FAMILY IS HERE” seems to offer the perfect virtual solution for the disintegration of the real Korean family. Simply by visiting the company’s website, anyone can request to purchase whatever service they require. While placing their order, customers communicate directly with Park herself, who collects their information. This data is then analyzed and incorporated into a monthly report that becomes part of the exhibition. For the month of October 2019, the most popular service among the visitors to the exhibition was to rent a person to fill in or accompany them while going to the bank or signing contracts, while the least popular services included renting a spouse, a fill-in for their job, or someone to make a complaint or protest. Among the new services that visitors requested were someone to deal with an “old bastard” or “mansplainer,” a substitute for a school project or graduate presentation, and someone to take care of their pets and plants. Evincing the new conception of a family in contemporary Korea, these results show that most young Korean adults are not concerned about the traditional composition of a family, as long as they have someone to give them stability and a sense of belonging. Perhaps their notion of “us” is simply whoever might accompany them through life.

Just as it began, this exhibition finishes with a question, which visitors find at the exit: “Can we live with them?” This question immediately summons another question: Who is meant by “them”? This question causes each visitor to reflect upon his or her own situation, to continue the conversation that they started with other people at the exhibition, and to extend the platform of agonism beyond the walls of the museum and into their everyday lives. As Mouffe asserts, true democracy exists in the power to change antagonism into agonism, and enemies into adversaries. Through her own venue of agonism, Hyesoo Park helps visitors take control of their thoughts and actions, not by condemning outsiders but by developing a new type of awareness. Art does not become political simply by dealing with political issues, but rather by making the invisible visible and the unthinkable thinkable, thus enabling us to perceive the hidden structure of the world with a new sensibility. By inventing and completing the world around “us,” the relational programs that Hyesoo Park built in Project Dialogue Vol. 4: Our Unknown Country operate as critical art, enacting just such a revolution of sensibility and aesthetics.