Young In Hong

Interview

CV

<Selected Solo Exhibitions / Site-specific Projects>

2018

The Moon’s Trick, Exeter Phoenix, Exeter

2017

The Moon’s Trick, Korean Cultural Centre, London

2016

A Fire that Never Dies, Cecilia Hillström Gallery, Stockholm

2015

Young In Hong 6/50, fig-2, ICA Studio & Theatre, London

2014

Image Unidentified, Banner project at Artsonje Centre, Seoul

2013

Floral Deception, Sindoh Art Space, Seoul

This is Not Graffiti, Cecilia Hillström Gallery, Stockholm

2012

City Rituals: Gestures, Artclub1563, Seoul

<Selected Group Exhibitions>

2019

What is Contemporary art? Daegu Art Factory, Daegu

2018

with weft, with warp, Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul

2017

Rethinking Craft: Between studio craft and contemporary art, Seoul Museum of Art Nam-Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul

Venice Agendas 2017: The Contract, Venice/ Turner Contemporary, Margate

Block Universe, London

2016

Making is Thinking is Making: La Nouva Arte Coreana, XXI La Triennale di Milano, Milan

2016 Art Paris Art Fair, South Korea Guest of Honour, [Performance programme], Grand Palais, Paris

2015

[ana] please keep your eyes closed for a moment, Maraya Art Centre, Sharjah

2014

Burning Down the House, Gwangju Biennale, Gwangju

Spectrum-Spectrum, PLATEAU, Seoul

Open Studio: The Public Domain, Delfina Foundation, London

2013

Making & Being, Korean Cultural Centre, Brussels

Tell Me Her Story, Coreana Museum of Art, Seoul

The Song of Slant Rhymes, Kukje Gallery, Seoul

2012

Playtime, Culture Station Seoul 284, Seoul

The Shade of Prosperity, Film Screening, Rivington Place, London

Plastic Nature, Galerie Vanessa Quang, Paris

2011

Korean Eye: Energy and Matter, The national Assembly, Seoul

2010

Korean Eye: Fantastic Ordinary, Saatchi Gallery, London

<Awards>

2011

Kimsechoong Art Prize, Korea

2003

Suk-Nam Art Prize, Suk-Nam Art Foundation, Korea

<Residencies>

2015

Seoul Art Space Geumcheon, Seoul

[Public Domain], Delfina Foundation, London

2014

[Performance as Process], Delfina Foundation, London

2013

ARKO Nomadic Artist in Residence, Chennai

Critic 1

Another Approach to Equality

Hye Jin Mun (Art Critic)

According to Young In Hong, her work is about seeking ways in which the concept of ‘equality’ can be questioned and putting them into practice through art. These words might remind one of sociopolitical activist art, which dominated the art scene of the 1980s and 1990s. In terms of subject matter, most of her works deal with those people whom society regards as minorities, and in terms of medium she often uses methods that are not usually associated with high art such as sewing and embroidery. Hong’s approach to the idea of equality is, however, considerably different from the familiar and typical modes of tackling sociopolitical issues. The voices that speak of what is marginal are easily subject to the danger of falling prey to an oppositional dichotomy. The label or category of minority itself is an obvious sign of approving the existing hierarchy between the central and the marginal, and the efforts to defend the rights of the marginal frequently turns into the struggle for recognition to replace the central with the marginal. How can we pay attention to those who are marginalized without categorizing them as a specific group or embrace the marginal without differentiating or objectifying them? Hong’s practice presents us with a small suggestion as to a possible answer to this difficult question.

There are two points for an artist to consider if s/he intends to embody equality in a visual language: one is a content-oriented embodiment using it as a subject; the other is to incorporate it into the production process or form. The former is the relatively easier and general approach, but it has an unavoidable limitation in that content and medium work separately. It is at this very point that Hong’s method stands out: in her work, not only the content but the process and the resulting body (form) likewise defy the established hierarchy, quietly but clearly. Consequently, equality operates and is achieved with respect to both content and form, namely, both internally and externally.

The most conspicuous feature is the use of needlework or a sewing machine. The low-wage labor of sewing, which is done largely by female factory workers in the region of Asia, is a good referent for otherness in terms of both gender and class. In fact, the artist learned this skill from the seamstresses working at Dongdaemun Clothing Market. Yet in Hong’s work sewing is employed to reflect neither femininity or Asianness nor a subcultural identity. The intent behind her utilization of sewing is not targeted on the portrayal of otherness itself but is to reveal the boundaries of which we have never been aware. An example would be the criteria for the category of high art. By adopting the element of needlework, which is excluded from the realm of fine arts as craftwork, in realizing the conceptual and intellectual content of the work, the artist blurs the divisions within the genre of high art and brings together differences. The fact that it not only criticizes the institution internal to art but also that it necessarily corresponds to the content of the work attests to the very depth of Hong’s work. For instance, Burning Love (2014) is an embroidery work of the spectacular scene of the candlelight vigil protesting against the import of U. S. beef in May 2008, which deals with the affections of ordinary citizens (especially teenage girls) who are not the protagonists of the official history of the event. The form of embroidery that requires the honest labor of making one stich at a time is an adequate medium to cast light on every individual who gathered in the streets voluntarily. Here, a large number of people participating in the protests are referred to not as members of a group like a race or a nationality but an assembly of different individuals, that is, a multitude. The small but passionate aspirations of each participant are stitched with much care, manifesting themselves as proud pages of history as a galaxy with a plethora of stars.

On the other hand, in her performance work, another medium for the investigation of the keyword of equality, social issues and fine art elements are more actively interlaced with one another. Owing to its attributes of chance and immateriality, performance can easily cast off the limitations of originality and uniqueness that works in the objet format have difficulty escaping from — even when using unconventional means such as sewing. Furthermore, the control of the work can be more impeded by the voluntary participation of the general public than when carried out by casted performers. 5100: Pentagon (2014), premiered at the Gwangju Biennale, is a performance piece where the volunteer audience performs the choreography inspired by the May 18 Gwangju Uprising. Participants vary every time, and so does the performance. As various groups of people from outside of the art scene act as subjects in creating a work of art, the performance opens up a small interstice in the closed category of the museum. As each of today’s different others ruminates on the painful history of Gwangju in his/her own way, they form a small temporary and loose solidarity. These ripples wipe out the border between art and non-art and what is experienced here lingers on in the minds of the participants.

In her recent work, Prayers (2017), embroidery and performance integrate. Hong transcribed a part of a news photo of a landscape of postwar Korea onto fabric in embroidery and played this like a “graphic score.” Her work of this method — also called “photo-score” — is the act of rewriting the mainstream history of Korea, which is South Korea-oriented and male-dominated. The trivial details irrelevant to the imparting of the message of the news photo are part of the unrecorded history. By erasing the center and slightly raising the details, the artist transposes the center of gravity of the historical narrative. The history, primarily rewritten through the artist’s embroidery, becomes a music score and once again undergoes a reversal. Even if there is just one score, its interpretation divides into as many as the number of the players. Each performer plays differently and each performance is thereupon a version of history written by an individual. As my experience and yours are different, the year 2019 as I remember it is inevitably different from the way you remember 2019. Accordingly, how inadequate must the mainstream history be that leaves aside all of these countless memories. Its interpretation varies depending on the performer, and those interpretations split into ceaseless derivative versions, muddling up you and me, man and woman, and Korea and other nations. In the middle of this, the boundaries between the artist and the audience and between art and society are blurred. A cheerful stage of hybridity where the history I wrote and the history you wrote coexist and harmonize; this is the way Hong sees difference, as it is the hope that she harbors.

In the Korean Artist Prize 2019 exhibition, Hong extends the concept of equality beyond humans to apply to non-human agents. Comprised of three new works, Sadang B (2019) attempts to rethink the dominant (human)-oriented viewpoint by positioning birds and animals as subjects. Here, one is driven to be confronted with a strange unfamiliarity: the ironic situation in which viewers are placed inside the birdcage looking out to the space where birds are; the improvisational performance by the musicians who are trying hard to become animals; the dance where performers mimic how females labor and how animals move. This discomfort is, in fact, a necessary emotion. For it allows one to realize how difficult it is to become the other on the one hand and on the other points out the value of the attempt to try to walk in the shoes of the weak, even though it would never come to pass. Hong pursues a delicate quest for a certain balance that is very particular and yet universal and individual and yet collective, and it is hoped that this quest of the artist is shared with many more people. In South Korea where dichotomous stances and loud voices are dominant, aimless resistance, non-group identified subjects, and non-divisive coexistence are such rare and scarce values. It is hoped that this exhibition will be an opportunity to witness the quiet permeation of its genuine radicality into the mind of each viewer.

Critic 2

Sadang B: Young In Hong

Sacha Craddock (Independent Critic and Curator)

‘Sadang’ means shrine but with a nod to the continuous, the title ‘Sadang B’ replaces a possible sense of the ultimate icon. The suggestion here is that Young In does not wish her exhibition to aim to function as the end of the subject or journey, but to be instead a mere participant in a series of actively asked questions. ‘Sadang B’ implies that there is also an A, a C, and perhaps even a plan D. This shrine is not the only shrine, and B is part of a range of categorization. This title immediately implies another, perhaps parallel, order, process and rationale. Life, goes on, it seems, elsewhere.

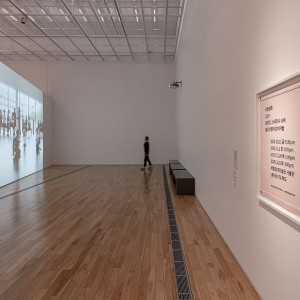

As a highly accomplished artist, Young In uses whatever medium seems right and relevant for whatever she needs to say at any particular time. Sadang B is an exhibition of three works, with three types of moment, action, and ritual, taking place in three different sections of the gallery. The artist’s characteristically generous repertoire is represented here, in part, by audience involvement with different forms of movement to improvised music, sewn objects, recorded bird sound, and choreographed movement.

The notion of the permanent is challenged by the temporary. A range of embroidery, collage, tapestry and drawing move from the fabulous to the perfunctory with work that mimics a change in a skyline, for instance, as it traces the outline of figures, buildings, trees and crossroads to become imbedded in a two-dimensional horizon. Often, once a line emerges and takes its role here, the everyday inevitably can be elevated into much greater theatre, and vice versa. The artist traces, literally, old photographs in her recent works, and tried to touch some of the shifts and disruptions in the history of Korea over the last thirty years. Utilizing the cultural and folkloric iconography of Korean culture, the artist hopes to forensically unearth something that is significant and yet perhaps unclear. A compression of space and experience runs alongside the visualization of past and current struggles in her native Seoul. For the artist, any rise in simplistic characterisation means that a wide-open pride in National identity has to be feared. Her process of sorting through found images and museum photo archives mixes with childhood, adolescent, and student memories to create a fundamental, and multilayered process of questioning for Young In, who now lives in England.

With sinister tweeting on one side, and simple ominous shadow on the other, the first piece, To Paint the Portrait of a Bird shows the artist seeming to already question notions of freedom. Who can be free to do whatever he, she or they, wants? A loud tweeting in this huge bird cage, and the implication is that you cannot get out, sits with fantastic heraldic embroidery, mustered and gathered together to conjure the most convincing equivalent of a series of coats of arms. This work, an engagement with belief, also draws a parallel with a hierarchy of species, of assumed differences between the animal or bird kingdom, for instance, and therefore the inevitable conclusion about any Nationalist thought that places human over human. Unconsciously border free, however, the birds which are sometimes outlined as shallow sewn objects, are brought together along with real shadows. Redolent of many cultures, birds from everywhere; penguins, ducks, and flamingos, seem to represent different countries to characterize local as well as other places and climates. Held on to, sewn or tacked into simple, decorous, delicate traditional icons, these apparently direct metaphors show the artist appearing to question this or any hierarchy, aware, anyway, that birds are capable of flying further and longer than any high-powered business woman or man.

There is no innocence anywhere and Young In trails, or sprinkles the subject of destruction and preservation, taste, history, and identity to run alongside and through her work. Questions about value, the role, absorption and rejection of cultural history prevail. What about the control of grand imperial vistas and colonial buildings? Should they be bought down or left to be overtaken by new histories? Young In talks about being disturbed, for example, by the full-scale demolition of the Japanese General Government Building, a Colonial building in Seoul. This place had great significance for her as a child because of the ‘lovely’ garden, in part. The government said the building ‘blocked the energy of the Nation’, the public agreed. It is impossible to argue about such a representation of a subjugation to an external power, and it was demolished in 1996.

Although of great significance, a shrine is still a construction. The role of the audience is key in that each spectator is identified with, a participant in, the artist’s active, three dimensional, questioning of change. The significance of the religious relic, itself a matter of belief, runs alongside the whole process of the making and perpetuating of art. It runs beside the fact that value, again so nebulous, lies not in the financial value of a material used, and in a different significance. Young In is playing with a whole building, and then destroying belief. Her work deals with manifestations of a recent past, the city outline that sways the way that art tells truth and lies at the same time. She plays with the way that history elevates elements, only to dash them because of a change in significance and circumstance. One person’s hero is another person’s personification of hell, after all, and Young In works between the construction of meaning in an artistic sense and the significance of memorialisation. From the outside she observes a country that seems to try to act tougher like a family putting the right foot forward and down.

At the beginning of the exhibition the audience starts with active involvement. Young In makes a shrine that has the depth, intensity and abstract use of a Confucian ancestral ceremony carried out by sons of the family while the women wait outside. She introduces an underlying theme to the exhibition which is very much about the way that women are meant to behave. So the audience starts out at the beginning in a cage, albeit with the ability to walk through. The audience is implicated, surrounded and involved in a way it cannot avoid, and then, next door, the same member of the audience becomes a spectator, listening through speakers as well as headphones. The second work, The White Mask is straight forward in its delivery but complex in its relation to the artist who asked, or perhaps instructed, musicians, from the celebrated Notes Inégales group in London to follow instructions. She asked them to play their classical instruments with their total personification, or animalization in mind. They become or became creatures and the result is clear, in a way. These musicians practice the deepest, frankest, most creative level of collaborative improvisation and music making. It was said at the time ‘but we are animals already.’ Young In is an accomplished musician, and much of her recent work, Prayers (2017) and Looking Down from the Sky (2017) involves the making and performing of scores often extrapolated from the outline of a historical photograph of Seoul.

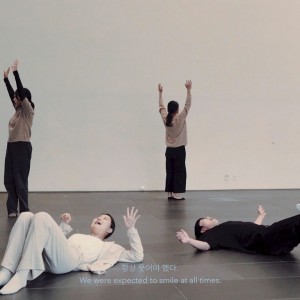

Un-Splitting consists in part of a performance projected onto the wall and an embroidered label announcing the schedule of further performances at unspecified spots in the lobby and outside the gallery. The performances are a response to the repeated movement of women working in factories found in photographs by the artist. Performers act out instructions to women factory workers, obeyed not so long ago. Studying images, like many she uses, found in the Seoul Museum of History, Young In works with performers and a choreographer to construct movement, bringing in the actions of perhaps even less ‘valuable’ animals and birds as well as that of women at work in factories. She says she actually senses women’s fight to address the idea that their labour is ‘lower’ than that of a man. Movement brings everything together in an attempt to see if by perhaps looking somewhere else, looking down, or up, and across species, there might be a better way to communicate, and therefore exist. A collective movement of the combined body of performers, some professional, some volunteers, is powerful and touching. Having advertised and recruited online, Young In has brought contemporary dancers, theatre actors, members of the general public and university and high school students together. Divided into two groups, each of six to seven performers, they reinforce apart from everything else the fact that women workers were expected to smile all the time. Workers were called by numbers not names, as well, not long ago; perhaps they still are? Each piece is different but connected. The tone the performers take is democratic but also influenced by whoever and what else is there. Performances programmed elsewhere other than in the gallery bring the work back to places Young In spent time in as a child, and where she now engages as an artist.

Attempting a complex but apparently sound method for renegotiating not only the representation, but the effect, of reality, Young In’s work is based very much around a precarious relationship to the past, about the way that it can be re-interpreted in different ways in terms of what is being looked at, preserved, re-considered, and surveyed in both pictorial and emotional terms. Aiming for a new way to communicate she is able to use what is out there, to transform, in terms of function, whatever it is that she traces and identifies. The outline of a horizon in a photograph, for instance, is used to write a score; the sewing machine turns into a musical instrument; the outline of a sewn, projected, drawn or collaged bird becomes the harbinger of good and bad, as well as the representation of trapped desire in a confident, heartening, but open contemplation of the design of political will.